4.3 Employment

The economy and the nature of employment significantly impact the lives of all Americans. Concurrently, they also give rise to numerous issues that affect millions across the nation. This section will explore several of these challenges.

Wages & Job Loss

Given the significant economic downturn that struck the United States starting in late 2007, it’s unsurprising that millions of jobs vanished over the past five years and wages have dwindled for numerous Americans. However, even prior to the recession’s onset, troubling signs were apparent in the American economy. These signs included a widespread decline in job opportunities across various sectors and a stagnation of wages.

These trends are partly due to the United States transitioning into a post-industrial economy, aligning with other industrialized nations. In this type of economy, information technology and service-based occupations take precedence over traditional manufacturing roles reliant on machinery. While physical strength and manual dexterity were essential for many industrial jobs, cognitive abilities and effective communication skills are now crucial for success in postindustrial occupations.

The transition to a postindustrial economy has brought both advantages and challenges for many Americans. The benefits of the information age are numerous and apparent, but there is also a downside for the workers who have been marginalized by post-industrialization and the globalization of the economy. Starting from the 1980s, numerous manufacturing companies relocated their operations from US urban centers to locations in the developing world, primarily in Asia and other regions, a phenomenon known as capital flight. Coupled with economic struggles, these developments have contributed to the loss of 5.5 million manufacturing jobs in the American economy since 2000 (Hall 2011).

Another issue of concern is outsourcing; where American companies opt to employ workers from abroad for tasks such as customer care and billing services, roles that were traditionally held by Americans. China, India, and the Philippines, with their proficient English-speaking workforces, are the main destinations for outsourcing by US companies. Dube and Kaplan (2010), Goldschmidt and Schmieder (2017), Dorn et al. (2018), and Drenik et al. (2020) have all found evidence indicating a growing trend of domestic outsourcing. Their studies reveal that workers who are outsourced are facing wage decreases in the United States, Germany, and Argentina, respectively.

These issues reflect a broader trend in the United States shifting away from jobs in goods production towards service sector employment. While some service jobs, particularly in fields like finance and technology, offer high salaries, many others involve low-wage positions such as those in restaurants and clerical work. These jobs typically pay less than the manufacturing roles they’ve replaced. Consequently, the average hourly wage for workers (excluding managers and supervisors) in the U.S., adjusted for inflation to 2009 dollars, only increased by one dollar from $17.46 in 1979 to $18.63 in 2009. This minimal change signifies a mere 0.2 percent annual increase over three decades, indicating stagnation in workers’ wages as noted by the Economic Policy Institute in 2012.

Recent wage changes also vary depending on an individual’s social class. From 1989 to 2007, while the average compensation for chief executive officers (CEOs) of large corporations surged by 167 percent, the average compensation for the average worker only increased by 10 percent (Mishel et al. 2009). Another striking perspective on this gap is evident when comparing CEO compensation to that of the typical worker. In 1965, CEOs earned on average twenty-four times more than the typical worker; by 2009, this figure had ballooned to 185 times greater (Economic Policy Institute 2012). These statistics highlight the increasing economic disparity in the United States, a concern that we will explore in more detail later in this module.

The decline of labor unions

One of the significant changes that came with industrialization in the nineteenth century was the emergence of labor unions and their clashes with management regarding wages and working conditions (Dubofsky and Dulles 2010). Workers were paid meager wages and toiled under dreadful conditions. A typical worker put in at least ten hours per day, six or seven days a week, with minimal or no extra pay for overtime, and no compensation for vacations or holidays. To enhance their wages and working conditions, many labor unions were established post-Civil War. However, they faced staunch resistance from corporations, the government, and the legal system. Companies shared information about suspected union members, effectively blacklisting them from employment. Striking workers often faced arrest for violating anti-strike laws, and when acquitted by juries, employers sought injunctions from judges to prevent strikes. Workers who persisted in striking were then held in contempt of court, bypassing jury involvement in the process.

Labor disputes were a significant feature of the Great Depression era, with many attributing their financial struggles to business leaders. Detroit’s auto plants witnessed extensive sit-ins and other forms of labor protests during this time. In reaction to these events, Congress enacted various laws granting workers fundamental rights such as a minimum wage, the freedom to join unions, a maximum limit on working hours, and other rights that are now considered standard in American labor practices.

Labor unions have experienced a decline in their influence, particularly with the shift from industrial to postindustrial economies and the dwindling manufacturing sector in the United States. Approximately forty years ago, a quarter of all private-sector nonagricultural employees were union members. By 1985, this percentage had decreased to 14.6, and presently, it stands at a mere 7.2 (Hirsch and Macpherson 2011). In response to this trend, unions have redoubled their efforts to recruit members. However, they have encountered obstacles within US labor laws that permit companies to impede union formation. For instance, following a successful unionization vote, companies can challenge the decision, leading to prolonged legal battles that delay union recognition. Consequently, the issues driving workers to seek union representation, such as low wages and inadequate working conditions, persist unabated in the interim.

As unions flourished in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, they played a crucial role in elevating workers’ wages. Conversely, the diminishing presence of unions has had a detrimental impact on wages. Mishel et al. (2009) offer two explanations for this decline. First, unionized workers typically earn about 14 percent more than their non-union counterparts, even when factors such as experience, education, and occupation are considered. This phenomenon, termed the union wage premium, has become less accessible to workers due to the dwindling membership in unions over the past four decades. Second, the diminishing influence of unions has resulted in reduced pressure on non-union employers to match the wage levels set by unionized workplaces.

Given that the union wage premium is higher for African Americans and Latinx/e people compared to Whites, the impact of declining unions on wages has likely been more pronounced for these groups than for Whites. Additionally, unionized workers are more inclined to have employer-provided health insurance with lower premiums and deductibles compared to nonunion workers. Consequently, the erosion of unions has resulted in a scenario where the typical worker today is less likely to have employer-sponsored health insurance and, if they do, is more likely to face higher premiums and deductibles.

Unemployment

Many unemployed individuals find themselves in involuntary unemployment. For them, the repercussions, both financial and psychological, can be severe, as highlighted in the news story that introduced this module.

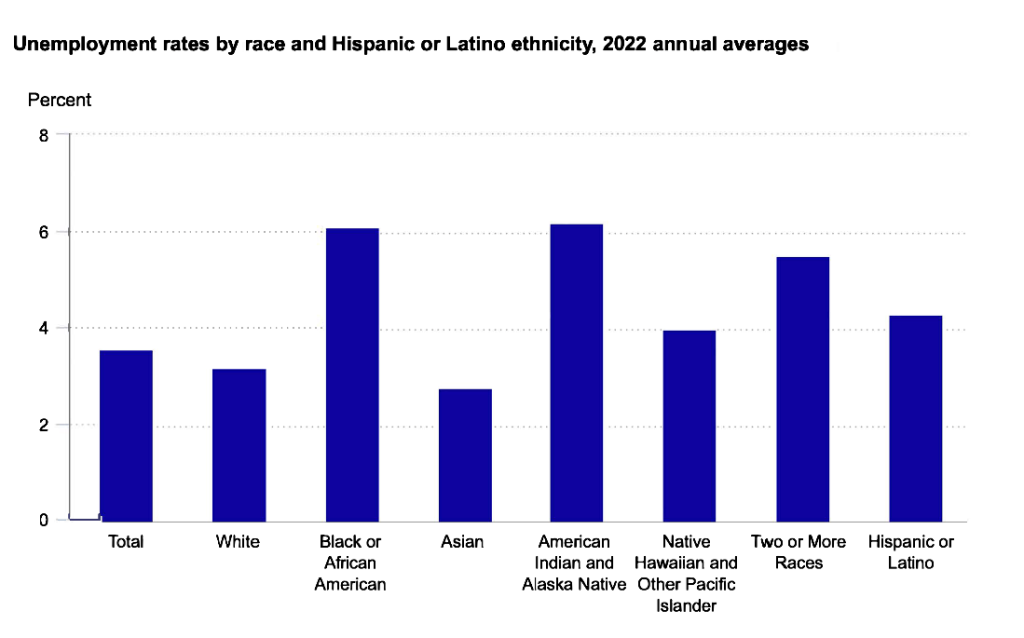

Unemployment rates fluctuate in accordance with economic conditions, reaching a peak of 10.2 percent in October 2009 during the Great Recession, which commenced nearly two years prior. By 2022, the national unemployment rate declined to 3.6 percent. However, irrespective of whether unemployment is high or low, it consistently differs across racial and ethnic lines. African American and Latinx/e American communities experience disproportionately higher unemployment rates compared to their white counterparts, as illustrated in Figure 6. “Unemployment rates by race and Hispanic or Latino ethnicity, 2022 annual averages.” Additionally, younger individuals face higher unemployment rates compared to older individuals. In February 2012, 23.8 percent of teenagers in the labor force (aged 16–19) were unemployed, a rate three times higher than that of adults. Among this demographic, African Americans experienced a particularly elevated unemployment rate of 34.7 percent, which was twice as high as the rate for whites in the same age group (U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics 2022).

Figure 6. Unemployment rates by race and Hispanic or Latino ethnicity, 2022 annual averages

Unemployment figures can be deceptive because they overlook individuals who are underemployed. This category encompasses not only the unemployed but also two other groups: (a) individuals who work part-time but desire full-time employment, often referred to as the marginally attached, and (b) those who have ceased job hunting due to unsuccessful searches. Numerous economists argue that underemployment offers a more precise gauge than unemployment of the extent of employment challenges faced by individuals.

For instance, in December 2011, amidst an 8.5 percent unemployment rate with 13 million individuals officially without work, the underemployment rate stood at 15.2 percent, encompassing 23.8 million individuals (Shierholz 2012). These numbers nearly double the official unemployment count. Demonstrating the racial and ethnic divide in unemployment, 24.4 percent of African American workers and 22.3 percent of Latinx workers experienced underemployment, compared to only 12.5 percent of white workers. Reflecting on the substantial underemployment during the Great Recession, one economist remarked, “When you combine the long-term unemployed with those who are dropping out and those who are working part time because they can’t find anything else, it is just far beyond anything we’ve seen in the job market since the 1930s” (Herbert 2010: A25).

As we’ve observed, unemployment tends to increase during economic downturns, and one’s race and ethnicity can influence the likelihood of experiencing unemployment. These findings align with the sociological imagination, as highlighted in “Module 1. The Importance of a Social Analytic Mind.” C. Wright Mills (1959) stressed that unemployment should be seen more as a societal problem rather than an individual challenge. When a significant portion of the population faces unemployment during an economic crisis, particularly when there is clear evidence of disproportionately higher unemployment rates among marginalized racial and ethnic groups who often lack access to education and training necessary for employment, it becomes evident that high unemployment rates reflect broader societal issues rather than isolated personal difficulties.

Various challenges hinder people of color from securing employment opportunities, thereby exacerbating racial and ethnic disparities in unemployment rates. The issues are highlighted below.

RACE, ETHNICITY, & EMPLOYMENT

As discussed in the text, individuals from racial minority groups are more likely to face unemployment or underemployment compared to white individuals. While differences in educational attainment contribute to these disparities, there are other significant challenges at play.

One notable issue is racial discrimination by employers, irrespective of their awareness of such behavior. A study detailed in Module 3 “Social Inequality,” conducted by sociologist Devah Pager (2003), illustrates this point. Pager’s study involved young white and African American men applying independently for various jobs in Milwaukee. Despite wearing similar clothing and presenting comparable levels of education and qualifications, some applicants disclosed a criminal record while others did not. Shockingly, African American applicants without criminal records were hired at the same dismal rate as white applicants with criminal records, providing compelling evidence of racial bias in hiring practices.

Pager and sociologists Bruce Western and Bart Bonikowski conducted a study on racial discrimination through a field experiment in New York City (Pager, Bonikowski, and Western 2009). They enlisted individuals of different racial backgrounds – white, African American, and Latinx – who were described as “well-spoken, clean-cut young men” (p. 781). These testers applied in person for entry-level service positions, such as retail sales and delivery drivers, which required only a high school education, and all had similar qualifications on paper. The results revealed that 31 percent of white testers received callbacks or job offers, while only 25.2 percent of Latinx testers and 15.2 percent of African American testers did. The researchers concluded that these findings contribute to a “large research program demonstrating the continuing contribution of discrimination to racial inequality in the post-civil rights era” (p. 794).

Further evidence indicates racial discrimination in hiring practices. Bertrand and Mullainathan (2004) conducted a study where job applications were submitted in response to help-wanted ads in Boston and Chicago. These applications were randomly assigned either a “white-sounding” name (e.g., Emily or Greg) or an “African American–sounding” name (e.g., Jamal and Lakisha). The results revealed that applications with white names received 50 percent more callbacks for job interviews compared to those with African American names.

Racial disparities in job access are partly influenced by differences in access to informal networks, which are crucial for job opportunities. Sociologist Steve McDonald and his colleagues discovered, in a study based on nationwide survey data, that people of color and women are less likely than white males to hear about available high-level supervisory positions through informal channels (McDonald, Nan, and Ao 2009).

As highlighted by these studies, research conducted by sociologists and other social scientists underscores the enduring impact of race and ethnicity on employment opportunities for Americans. This research consistently demonstrates the presence of discrimination, whether conscious or unconscious, in the hiring process, as well as disparities in access to informal networks which play a crucial role in securing employment. By revealing such evidence, these studies emphasize the urgency of addressing issues related to discrimination, equitable access to informal networks, and other contributing factors that perpetuate racial and ethnic disparities in employment.

Bertrand, Marianne and Sendhil Mullainathan. 2004. “Are Emily and Greg more Employable than Lakisha and Jamal? A Field Experiment on Labor Market Discrimination.” American Economic Review 94(4): 991-1013.

McDonald, Steve, Lin Nan, and Dan Ao. 2009. “Networks of Opportunity: Gender, Race, and Job Leads.” Social Problems 56(3):385–402.

Pager, Devah. 2003. “The Mark of a Criminal Record.” American Journal of Sociology 108(5): 937–975.

Pager, Devah, Bart Bonikowski, and Bruce Western. 2009. “Discrimination in a Low-Wage Labor Market: A Field Experiment.” American Sociological Review 74(5): 777–799.

The impact of unemployment

While the initial news article shared in this module provided a poignant portrayal of individuals seeking assistance at food banks due to unemployment, survey data also present stark evidence of the social and psychological impacts of joblessness. In July 2010, the Pew Research Center released a report derived from a survey involving 810 adults who were either presently unemployed or had experienced unemployment since the onset of the Great Recession in December 2007, alongside 1,093 individuals who had remained employed throughout the recession (Morin and Kochhar 2010). The report, titled “Lost Income, Lost Friends—and Loss of Self-Respect,” succinctly captured its key findings.

Among those who endured long-term unemployment, a staggering 44 percent reported significant life-altering effects due to the recession, contrasting sharply with only 20 percent of those who had never faced unemployment. Over half of those long-term unemployed witnessed a decrease in their family income, while more than 40 percent indicated strained family relations and loss of contact with close friends. Additionally, 38 percent admitted to a decline in self-respect due to unemployment. Financial strain was prevalent, with one-third struggling to meet rent or mortgage payments, compared to just 16 percent of those unaffected by unemployment during the recession. Half resorted to borrowing money from relatives or friends to cover expenses, a stark contrast to the 18 percent among the never unemployed. Sleep difficulties afflicted nearly half of all unemployed individuals, and 5 percent reported grappling with substance abuse issues. These statistics collectively portray the distressing social and psychological toll of unemployment during the Great Recession, which commenced in late 2007.

Corporations

One significant aspect of modern capitalism that sparks debate is the corporation, an organized entity with a legal identity distinct from its members, granting it the authority to enter contracts.

Adam Smith, the architect of capitalism, envisioned a system where individuals would possess the means of production and engage in competitive pursuit of profit. This blueprint was initially adopted by the United States during its early phase of industrial development. However, post-Civil War, a significant shift occurred, with corporations swiftly supplanting individuals and families as the proprietors of production means and as the primary contenders for profit. As these corporate entities burgeoned in the aftermath of the Civil War, they promptly sought to dominate their respective markets through tactics such as acquiring competitors and driving others out of business. This endeavor often involved engaging in unethical practices such as bribery, kickbacks, and intricate financial maneuvers. Moreover, these corporations were notorious for establishing workplaces characterized by deplorable conditions. Their dubious financial dealings earned their top executives the moniker “robber barons” and prompted the federal government to enact the Sherman Antitrust Act of 1890, aimed at prohibiting anti-competitive behavior that inflated prices (Hillstrom and Hillstrom 2005).

Over a hundred years later, corporations have proliferated in both quantity and scale. While the United States boasts several million corporations, the majority are relatively modest in size. Conversely, the largest five hundred corporations each generate annual revenues surpassing $4.3 billion (as of 2011) and employ thousands of individuals. Cumulatively, their assets reach into the trillions of dollars (CNN Money 2015). As of 2020, the Fortune 500 companies represent approximately two-thirds of the United States’ gross domestic product with approximately $14.2 trillion in revenue, $1.2 trillion in profits, and $20.4 trillion in total market value. It’s accurate to assert that these entities wield significant control over the nation’s economy. Together, they account for the bulk of the private sector output, employ millions, and generate revenues comparable to a substantial portion of the U.S. gross domestic product. The enormity and influence of corporations often dampens the competitive spirit intrinsic to capitalism. For instance, several industries, such as breakfast cereals, are dominated by just a handful of corporations, which curtails competition by limiting product variety and the number of competitors, leading to higher prices for consumers (Parenti 2011).

In recent decades, there has been a notable increase in the prevalence of multinational corporations, which are companies headquartered in one country but have operations spread across multiple nations (Wettstein 2009). Multinational corporations based in the United States and their overseas subsidiaries collectively possess assets exceeding $17 trillion and provide employment to over 31 million individuals (US Census Bureau 2012). Remarkably, the assets of the largest multinational corporations surpass the wealth of many sovereign nations. Frequently, these corporations establish operations in developing countries where low labor costs make them attractive investment destinations. In these nations, many multinational employees toil in sweatshops for meager wages and endure inadequate living conditions. Critics argue that multinational corporations not only mistreat workers in these countries but also exploit their natural resources. Conversely, proponents argue that these corporations bring employment opportunities to impoverished nations and contribute to their economic advancement. The ongoing debate surrounding multinational corporations underscores the contentious nature of their dominance and its implications.

Economic inequality

In 2011, the Occupy Wall Street movement gained widespread recognition for drawing attention to economic inequality. By highlighting the gap between the wealthiest 1% and the remaining 99%, they criticized the increasing concentration of wealth among the ultra-rich and the widening inequality over recent decades. This movement’s slogan, “We are the 99%,” symbolized the collective discontent with this disparity. Further exploration of economic inequality is warranted in this context.

OCCUPY WALL STREET

Prior to 2011, economic inequality in the United States undoubtedly existed and had notably escalated since the 1970s. However, while social scientists were concerned about economic inequality, it did not capture the attention of the mainstream news media. Consequently, since economic inequality was largely overlooked by the news media, it also failed to resonate as a significant concern among the public. Everything changed on September 17, 2011, when a large group identifying themselves as “Occupy Wall Street” marched through New York City’s financial district. They established encampments that lasted for weeks, protesting the major banks and corporations for their role in the 2007-2008 economic collapse and highlighting their influence over the political system. This movement quickly gained momentum, with similar Occupy protests popping up in over one hundred U.S. cities and hundreds more worldwide. Their rallying cry, “We are the 99%,” echoed across the nation as “occupy” became a commonly used verb.

By winter, most Occupy encampments had disbanded, primarily due to legal crackdowns or harsh weather conditions. Nonetheless, by this time, the Occupy protesters had garnered widespread attention from the news media. According to a December 2011 poll conducted by the Pew Research Center, 44 percent of Americans voiced their support for the Occupy Wall Street movement, while 35 percent expressed opposition. Nearly half (48 percent) indicated agreement with the movement’s concerns, whereas 30 percent disagreed. The poll also revealed that 61 percent of respondents believed that the US economic system “unfairly favors the wealthy,” while 36 percent deemed it fair to all Americans. Moreover, a significant majority (77 percent) stated that “there is too much power in the hands of a few rich people and corporations.” Interestingly, these opinions varied notably based on political party affiliation. For instance, 91 percent of Democrats agreed that a select few rich individuals and corporations held too much power, compared to 80 percent of Independents and only 53 percent of Republicans. Despite political disagreements, Occupy Wall Street effectively highlighted economic inequality and associated issues on a national scale. Within a mere few months in 2011, it significantly impacted the discourse.

Pew Research Center. 2011. “Frustration with Congress Could Hurt Republican Incumbents.” Retrieved from (https://www.pewresearch.org/politics/2011/12/15/frustration-with-congress-could-hurt-republican-incumbents/).

Vanden Heuvel, Katrina. 2012. “The Occupy Effect.” The Nation. Retrieved from (http://www.thenation.com/blog/165883/occupy-effect?rel=emailNation).

Let’s begin by reviewing economic inequality, which is the degree of difference in wealth between the affluent and the impoverished. In virtually all societies, there are varying levels of wealth among individuals, but the crucial aspect to consider is the magnitude of these differences. When there is a significant gap between the wealthy and the poor, we describe this as substantial economic inequality. Conversely, when the gap is minimal, we characterize it as relatively limited economic inequality.

Viewed through this lens, the United States displays a significant level of economic inequality. A common method for assessing this inequality involves arranging the nation’s families by income, dividing them into fifths from lowest to highest. This results in the poorest fifth, the second fifth, and so forth, until reaching the wealthiest fifth. By doing so, we can analyze what proportion of the nation’s total income each fifth possesses. The data reveals that the poorest fifth of families only holds 3.3 percent of the nation’s income, while the richest fifth enjoys a substantial 50.2 percent. Another perspective is that the wealthiest 20 percent of the population possesses as much income as the remaining 80 percent combined.

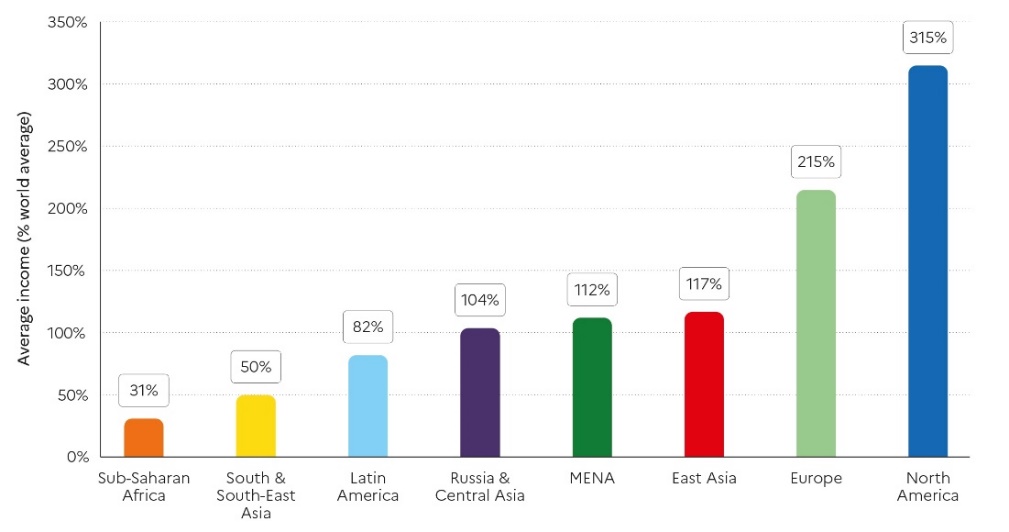

This level of inequality is unparalleled among industrialized nations. Figure 7. “Average income across world regions, 2021,” illustrates average incomes across various world regions, represented as a percentage of the global average income of $18,250 per year. In Sub-Saharan Africa, the average income is 31% of the global average, while in South and Southeast Asia, it stands at 50% (Chancel et al. 2022). Latin America, East Asia, and Russia and Central Asia hover around the global average. Europe exceeds the global average by more than double (215%), while North America triples it. Consequently, North Americans earn 6 to 10 times more on average than Sub-Saharan Africans and South and Southeast Asians, whereas East Asians earn half of what Europeans do.

Figure 7. Average income across world regions, 2021

If we were to analyze income earned per hour worked, the disparity between affluent and impoverished countries would be even more pronounced (due to Sub-Saharan Africans and Southeast Asians working around 30% more hours per year than Europeans and North Americans). Additionally, the hourly income gap between Europeans and North Americans would decrease by 30% because North Americans work longer hours. This underscores the importance of considering various indicators such as time spent at work, quality of public services and infrastructure, civic and human rights, and environmental standards alongside income to gauge living standard inequalities across nations. There is no singular indicator to measure inequality across nations and individuals globally (Chancel et al. 2022).

APPLYING A SOCIAL ANALYTIC MINDSET

PEW Research Center: Poverty & Income Calculator

Read the article “Are you in the American middle class?,” and complete the “Income Calculator Exercise.”

- See where you are in the distribution of Americans by income tier.

- Compare yourself to others in the U.S. with similar demographic data.

- Think about it. . . after reading the article, what trends are indicated in the distribution of wealth among classes. Does this research align with your current thinking on class?

Pew Research Center. 2020. “Are You in the American Middle Class?” Pew Research Center: Washington, D.C. Retrieved March 3, 2024 (http://www.pewresearch.org/topics/poverty/).