5.3 Health

When we look at health and healthcare in the United States, we find both positive and negative aspects. Let’s start with the positive news, which is significant. Health has gotten better over the past hundred years, mainly because of improved public cleanliness and finding antibiotics. Illnesses like pneumonia and polio, which used to be fatal or cause severe disability, are either extremely rare today or can be treated with modern medicines. Additionally, other medical breakthroughs and progress have lessened the impact and severity of major illnesses, such as various forms of cancer, and have extended our lifespans.

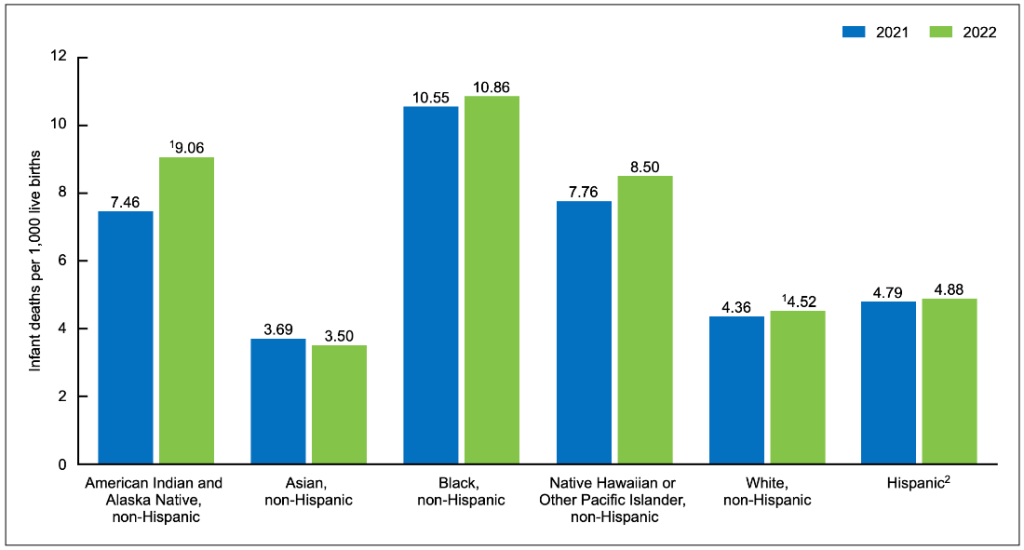

Due to these and other reasons, the average lifespan in the U.S. increased from around 47 years in 1900 to about 78 years in 2010. A recent report by the National Center for Health Statistics reveals concerning trends in infant mortality rates in the United States (Ely and Driscoll 2023). In 2022, there was a 3% increase in the provisional infant mortality rate compared to 2021, marking the first rise in this rate since 2001-2002 (see Figure 13). Prior to this increase, there had been a consistent decline in the infant mortality rate, which had decreased by 22% from 2002 to 2021 (see Figure 6. “Infant Mortality Rate, By Race and Hispanic Origin: United States”).

Smoking rates also went down considerably, and the percentage of male smokers decreased from 51 percent in 1965 to 23 percent in 2009, and female smokers from 34 percent to 18 percent in the same period (National Center for Health Statistics 2011). Additionally, over the past three decades, various policies have significantly lowered levels of lead in young children’s blood: around 88 percent of children had unsafe lead levels in the mid-1970s, compared to less than 2 percent three decades later (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention 2007).

Figure 13. Infant mortality rate, by race and Hispanic origin: United States

Unfortunately, there’s quite a bit of bad news too. Despite the improvements we mentioned earlier, the United States isn’t doing as well as most other rich democracies in terms of health measures. Even though it’s the richest country globally, it falls behind in several health areas. Additionally, around 14.5 percent of American households, nearly 49 million people, struggle with “food insecurity” at least part of the year, meaning they don’t always have enough money for proper food and nutrition. More than one-fifth of all kids live in such households (Coleman-Jensen et al. 2011). Over 8 percent of babies are born underweight (less than 5.5 pounds), which can lead to health issues later on. This rate has been going up since the late 1980s and is now higher than in 1970 (National Center for Health Statistics 2011). Additionally, rates of childhood obesity, asthma, and other chronic conditions are increasing, with about a third of kids now considered obese or overweight (Van Cleave et al. 2010). It’s clear that the United States still has a lot of work to do to improve the health of the nation.

Health issues in the United States aren’t distributed fairly. They tend to affect people who are poor, from specific racial or ethnic groups, and sometimes affect women or men more depending on the issue. Social epidemiology is the study of how health and sickness change based on factors like where people come from or how much money they have. These differences are called health disparities. In the United States, there are many health disparities when we look at social epidemiology. This means that both being healthy and being sick can show and make worse the unequal parts of society. Now, let’s look at the most important health disparities, starting with physical health and then mental health.

Health Disparities

Besides having less money, poor people also suffer from much worse health. The government and experts in medicine and academia are increasingly realizing that your social class plays a big role in your health and sickness (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention 2011).

Various health measures highlight the connection between social status and health in the United States. Each year, the government conducts a survey where people rate their health. Individuals with lower incomes are much more likely to report their health as only fair or poor compared to those with higher incomes. While these self-reports are based on personal opinions and may vary in interpretation, objective health measures also confirm a strong link between social class and health (National Center for Health Statistics 2011).

HEALTH PROBLEMS FACING POOR CHILDREN

When we talk about health differences, some of the most concerning evidence involves kids. According to a recent report by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, “The data illustrate a consistent and striking pattern of incremental improvements in health with increasing levels of family income and educational attainment: As family income and levels of education rise, health improves. In almost every state, shortfalls in health are greatest among children in the poorest or least educated households, but even middle-class children are less healthy than children with greater advantages.” Government data highlights how poverty affects kids in the country:

- Kids born to poor moms are more than twice as likely to be born with low birth weight compared to those born to wealthier moms.

- By 9 months old, poor kids are already more likely to have health issues and lower brain development and social skills.

- By age 3, poor kids are much more likely to have asthma compared to kids whose families make more than 150 percent of the poverty line.

- According to their parents, poor kids are almost five times more likely (33 percent compared to 7 percent) to be in less-than-good health.

In these ways and others, kids in low-income families are more likely to have health problems than kids in richer families, and many of these issues continue into teenage years and adulthood. The poor health of these kids has a big impact on their whole lives. As sociologist Steven A. Haas and his colleagues note, “A growing body of work demonstrates that those who experience poor health early in life go on to complete less schooling, hold less prestigious jobs, and earn less than their healthier childhood peers.”

One reason why poor children aren’t as healthy is because their families often deal with a lot of different kinds of stress. Another reason is that their families often struggle to have enough food, especially if they live in cities where there’s more lead and pollution in their neighborhoods. Kids from low-income families also tend to watch more TV than kids from wealthier families, which makes them less active. This lack of physical activity is another reason why their health isn’t as good. Lastly, their parents are more likely to smoke cigarettes compared to wealthier parents. Breathing in the smoke from these cigarettes, even secondhand, can make their health worse.

The strong proof that poverty negatively impacts the health of children from poor families emphasizes the importance for the United States to take every possible action to lessen these impacts. Investing money to alleviate these effects will be highly beneficial in the long term: These children will experience fewer health issues as they mature, resulting in lower healthcare costs for the United States. Additionally, they will have better academic performance and higher incomes as adults. Therefore, enhancing the health of underprivileged children will not only benefit them in the short and long term but also contribute to the overall economic and social well-being of the nation.

Haas, Steven A., Maria Glymour, and Lisa Berkman. 2011. “Childhood Health and Labor Market Inequality Over the Life Course.” Journal of Health and Social Behavior 52(3): 298–313

Kaplan, George A. 2009. The Poor Pay More: Poverty’s High Cost to Health. Princeton, NJ.

Murphey, David, Bonnie Mackintosh, and Marci McCoy-Roth. 2011. “Early Childhood Policy Focus: Health Eating and Physical Activity.” Early Childhood Highlights 2(3): 1–9.

Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. 2008. “America’s Health Starts With Healthy Children: How Do States Compare?” Princeton, NJ: Robert Wood Johnson Foundation.

Global Pandemics

Acute infectious disease outbreaks, especially those caused by respiratory pathogens, present significant challenges globally. Diseases like tuberculosis, severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS 2003), Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS), H1N1 pandemic influenza, and seasonal influenza have highlighted the world’s capacity for rapid response. Each outbreak offers valuable lessons for enhancing detection, surveillance, medical countermeasure development, and other vital aspects of prevention, readiness, and response. Additionally, these events emphasize the importance of fairness in pandemic preparedness and response efforts. This includes promoting transparency in product pricing, facilitating technology transfers, and ensuring equitable access and benefit sharing (World Health Organization 2022).

Despite improvements in health security and strengthening of health systems, the emergence and rapid spread of the SARS-CoV-2 virus highlighted significant gaps in both national and international preparedness for respiratory pathogens. COVID-19 is the disease caused by the SARS-CoV-2 coronavirus. It usually spreads between people in close contact (World Health Organization 2023). The COVID-19 pandemic underscored the importance of having robust health systems and global health security capacities to effectively respond to such crises. Additionally, it exposed how pre-existing inequalities are exacerbated during epidemics and pandemics, affecting all segments of society. Sectors that previously overlooked contingency planning for public health emergencies have now gained firsthand experience in preparing for such events.

Numerous initiatives are ongoing to learn from the COVID-19 pandemic and turn insights into actions, including several led by the World Health Organization (WHO). One of these initiatives is aimed at enhancing pandemic preparedness planning based on how diseases spread. Known as the Preparedness and Resilience for Emerging Threats (PRET), this effort has created guidance and tools for countries to update their pandemic plans specifically focusing on respiratory pathogen outbreaks.

Healthcare systems

Previous epidemics and virus outbreaks have informed global scientists and governments on how to prepare for future threats. In the case of the United States, the response has been distinct. For instance, during the Ebola outbreak in 2014, the U.S. established the Directorate for Global Health and Security and Biodefense (Ray and Rojas 2020). Despite the Ebola virus claiming over 11,000 lives worldwide, only two deaths occurred in the U.S. However, in 2018, the Trump Administration dissolved this team, with Trump himself expressing ignorance about it during a White House briefing on March 13, 2020 (Dozier and Bergengruen 2020).

This lack of accountability and governmental failure is not unprecedented, particularly within certain vulnerable communities. Roberts (1999) conducts a historical legal analysis, revealing how U.S. policies have systematically oppressed Black motherhood and womanhood from chattel slavery to the present day. Additionally, Watkins-Hayes (2019) illustrates how the courts neglected women diagnosed with HIV/AIDS in the 1980s, emphasizing their struggle for survival during the epidemic. Watkins-Hayes (2019) advocates for an HIV/AIDS safety net providing healthcare access, economic aid, social support, and avenues for political engagement, suggesting a model applicable to COVID-19, especially considering its disproportionate impact on racial and ethnic minorities. As stated by the Combahee River Collective (1983), “If Black women were free, it would mean that everyone else would have to be free since our freedom would necessitate the destruction of all the systems of oppression.” According to the World Health Organization (2024), “preparedness works.” Investing in functional capacities, interconnected systems, and critical infrastructure improves emergency response. Pandemic preparedness relies on comprehensive action from governments and society. This includes strong leadership, community engagement, and cross-sector collaboration. In our interconnected world, what affects one community impacts others. Promoting public health and scientific understanding facilitates acceptance of interventions. Priority should be given to vulnerable populations globally. Response efforts must be agile, monitoring developments, planning contingencies, and learning from experience.

Vaccinations and immunizations

Vaccines have been instrumental in safeguarding public health against infectious diseases. In the United States, their development has progressed through centuries, marked by key milestones and medical advancements. Edward Jenner coined the term “vaccine” in 1796 after successfully inoculating a boy against smallpox using cowpox lesions (Saleh et al. 2021). In 1872, Louis Pasteur created the first laboratory-produced vaccine for fowl cholera. Significant strides were made with vaccines for diseases such as diphtheria, tetanus, influenza, yellow fever, polio, measles, mumps, rubella, and varicella in the 20th Century.

The vaccine development process includes: 1) Research and Discovery; 2) Proof of Concept; 3) Clinical Trials; and 4) Regulation and Approval (CDC 2023). This process can take 10-15 years of laboratory research, often through collaboration between private industry and universities. Initial testing in animal models is done to assess immune response later in humans. Three phases of trials evaluate safety, immune response, dosage, effectiveness, and side effects. Lastly, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) oversees stages to ensure safety and efficacy before recommending vaccines for use.

During the COVID-19 Pandemic, Operation Warp Speed accelerated vaccine development while maintaining safety standards through government funding and collaboration. FDA’s fast track designation expedites review for critical vaccines like those for COVID-19 without compromising safety or efficacy. The history of vaccine development in the United States illustrates scientific progress, regulatory oversight, and collaborative efforts that have significantly benefited public health by curbing infectious diseases’ spread (The College of Physicians of Philadelphia 2024).

Immunity, which refers to the body’s ability to resist disease, plays a vital role in protecting individuals from infections and promoting overall health. Vaccines are essential for training the immune system to combat particular diseases without individuals needing to become ill initially, thereby boosting acquired immunity (Pfizer 2024).

Skeptics and misinformation

The COVID-19 pandemic has led to a considerable loss of life worldwide, with estimates indicating over 7 million confirmed deaths attributed to COVID-19 reported globally as of March 9, 2024 (World Health Organization 2024b). Estimates suggest that the total number of deaths directly or indirectly linked to the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020 and 2021 was about 14.9 million worldwide. This underscores the significant impact of the pandemic beyond the confirmed COVID-19 deaths (UN Department of Economic and Social Affairs 2021). Skepticism about the COVID-19 pandemic and its vaccines has been a major issue, influenced by factors like misinformation, distrust, and personal beliefs. Misinformation during the COVID-19 pandemic has profoundly affected public health, individual actions, and government strategies worldwide. It has spurred vaccine hesitancy, reluctance to wear masks, and the adoption of unproven treatments, leading to higher illness rates during the pandemic (Caceres et al. 2022). Misinformation has also triggered rumors, stigma, discrimination, unfounded theories, and influenced public beliefs and attitudes (Nelson et al. 2020). These factors have hindered efforts to control the spread of COVID-19 and manage its impact on society.

Employing a social analytic mindset is crucial during global pandemics as it enables individuals to assess information accurately, make informed decisions, and navigate the vast amount of often conflicting data and misinformation circulating in the public sphere. With the rapid spread of information through various media channels, including social media, critical thinking allows individuals to discern between credible sources and misinformation, thus reducing the risk of spreading falsehoods that could exacerbate fear and panic. Critical thinking skills help people to question assumptions, evaluate evidence, and consider multiple perspectives, enabling them to interpret complex scientific findings, understand public health guidelines, and discern between legitimate public health measures and conspiracy theories. By applying critical thinking, individuals can better protect themselves and their communities by making well-informed choices about health behaviors, vaccination, and adherence to public health guidelines, ultimately contributing to collective efforts to mitigate the impact of pandemics.