6.4 Social Movements & Activism

Collective behavior, a term used by sociologists, encompasses a range of behaviors involving large groups of people. Specifically, collective behavior refers to relatively spontaneous and unstructured actions by individuals influenced by others. Relatively spontaneous implies a mix of spontaneity and planning, while relatively unstructured suggests a blend of organization and unpredictability. Some forms of collective behavior are more spontaneous and unstructured than others, and some involve coordinated actions rather than mere influence. Overall, collective behavior is considered less spontaneous and structured compared to conventional behavior in familiar settings like classrooms or workplaces.

As previously mentioned, collective behavior encompasses various behaviors that may not share much in common beyond their classification as such. This section discusses several common forms of collective behavior, including crowds, mobs, panics, riots, disaster behavior, rumors, mass hysteria, moral panics, and fads and crazes. Some of these forms, like crowds, panics, riots, and disasters, involve people physically present and interacting, while others, such as rumors, mass hysteria, moral panics, and fads and crazes, involve individuals who may be geographically distant but share common beliefs or concerns.

Social movements represent another significant form of collective behavior. The study of social movements gained significant traction in the 1960s and 1970s, overshadowing research on other types of collective behavior. Consequently, the latter part of this module is dedicated exclusively to exploring social movements.

Crowds

A crowd refers to a large group of people coming together for a shared short-term or long-term goal. Sociologist Herbert Blumer (1969) categorized crowds into four main types based on their purpose and behavior: casual crowds, conventional crowds, expressive crowds, and acting crowds. Additionally, scholars have identified a fifth type known as protest crowds.

A casual crowd consists of individuals coincidentally gathered in the same place at the same time, lacking a significant common bond or shared purpose. An example is people waiting to cross a busy city intersection; though they share the immediate goal of crossing, their connection is fleeting. According to Erich Goode (1992), members of casual crowds typically share only their physical location, lacking deeper commonalities. Goode suggests that these crowds don’t exhibit true collective behavior, as their actions generally conform to societal norms for such situations.

Conventional crowd

A conventional crowd consists of individuals gathering for a particular purpose, such as attending a movie, play, concert, or lecture. According to Goode (1992), conventional crowds typically engage in behavior that is orderly and structured, reflecting their name. Unlike crowds exhibiting collective behavior, conventional crowds adhere to societal norms and expectations.

Expressive crowd

An expressive crowd consists of individuals coming together primarily to share and express various emotions. Examples include gatherings such as religious revivals, political rallies supporting a candidate, and festivities like Mardi Gras. According to Goode, the central aim of expressive crowds is to collectively experience and display emotions:

… is belonging to the crowd itself. Crowd activity for its members is an end in itself, not just a means. In conventional crowds, the audience wants to watch the movie or hear the lecture; being part of the audience is secondary or irrelevant. In expressive crowds, the audience also wants to be a member of the crowd, and participate in crowd behavior—to scream, shout, cheer, clap, and stomp their feet (1992:23).

A typical crowd can transform into an expressive one, like when moviegoers start shouting if the film projector malfunctions. This blurring distinction between conventional and expressive crowds suggests their fluid nature. Expressive crowds are characterized by heightened emotions and outward expression, as seen in the movie theater example. In these crowds, individuals participate in collective behavior driven by excitement and emotional reactions.

Acting crowd

An acting crowd takes a step further from an expressive crowd by engaging in violent or destructive behavior, like looting. A classic example is a mob, which is highly emotional and prone to violence. In historical contexts like the Wild West, mobs often carried out vigilante justice, bypassing trials and resorting to lynching. Lynch mobs, particularly prevalent in the South post-Reconstruction, targeted thousands of individuals, predominantly African Americans, in what would now be classified as hate crimes. Another form of acting crowd is a panic, characterized by sudden and self-destructive reactions, such as stampedes during emergencies or rushes into stores during sales. Acting crowds can escalate into full-scale riots when they become uncontrollable, a phenomenon we will touch on shortly.

Protest crowd

Identified by Clark McPhail and Ronald T. Wohlstein (1983), the protest crowd is a type of crowd that forms specifically for expressing dissent on political, social, cultural, or economic matters. Examples include sit-ins, demonstrations, marches, or rallies where individuals unite to voice their grievances or advocate for change.

Riots

A riot is a sudden eruption of violence involving a large group of people. While the term riot carries negative connotations, some scholars have used alternative terms like urban revolt or urban uprising to describe the social unrest witnessed in many U.S. cities during the 1960s. However, most scholars studying collective behavior still use the term “riot” without inherently attaching positive or negative judgments, and we adopt this neutral stance here.

Regardless of terminology, riots have been part of American history since colonial times. Colonists frequently rioted over issues such as “taxation without representation” during the 17th and 18th centuries (Rubenstein 1970). Estimates suggest between 75 and 100 riots occurred between 1641 and 1759. During the American Revolution, additional riots erupted as colonists resorted to violence against British rule. After the nation’s founding, riots persisted, with indebted farmers often rebelling against state authorities. One notable example is Shays’s Rebellion, a significant event in U.S. history, which originated as a riot involving hundreds of people in Springfield, Massachusetts.

Rioting surged in the early 19th century, becoming a regular occurrence. Rosenfeld (1997) notes that rioting was pervasive, with nearly three-fourths of U.S. cities experiencing at least one major riot, making it as common as voting or working for civilians. Native-born Whites predominantly targeted African Americans, Catholics, and immigrants in these riots. Abraham Lincoln remarked in 1837 that mob outrages were commonplace across the nation (Feldberg 1980).

Even after the Civil War, rioting persisted. White hostility towards Chinese immigrants stemmed from fears of job competition and suppressed wages. Additionally, labor riots erupted as workers protested harsh working conditions and low pay.

Race riots were prevalent in the early 20th century, with Whites attacking African Americans in major U.S. cities. In 1917, a significant riot in East St. Louis, Illinois, resulted in the deaths of 39 African Americans and 9 whites. Subsequent riots instigated by Whites occurred in at least seven more cities in 1919, leading to numerous casualties (Waskow 1967). During the 1960s, Northern cities witnessed riots as African Americans responded to instances of police brutality and unfair treatment. Estimates suggest that between 240 to 500 riots occurred during the decade, involving anywhere from 50,000 to 350,000 participants (Downes 1968; Gurr 1989).

Types of riots

Various types of riots can be categorized based on the motivations and objectives of the participants. One commonly used classification, proposed by McPhail (1994), distinguishes between protest riots and celebration riots. Protest riots stem from dissatisfaction with political, social, cultural, or economic issues, whereas celebration riots arise from the exuberance of an event or outcome, like the unruly festivities following a football team’s championship win. Protest riots are inherently political, while celebration riots lack political motivation.

Another widely recognized classification categorizes riots into four types: purposive, symbolic, revelous, and issueless (Goode 1992). Purposive riots stem from dissatisfaction with a specific issue and aim to achieve a particular goal related to that issue. Examples include colonial riots and many prison riots in the U.S. Symbolic riots, on the other hand, express general discontent without targeting specific objectives, such as the early 20th-century riots by whites. Revelous riots, as previously discussed, are celebratory in nature, while issueless riots lack a clear purpose or basis, like the looting and violence observed during citywide power outages. Understanding the participants’ demographics is crucial in comprehending riots.

Social movements

A social movement is when many people come together to either promote or hinder social, political, economic, or cultural change. Later in this module, we’ll look deeper into social movements, but for now, recognize them as a crucial type of collective action that influences social change.

Disaster behavior

A disaster refers to an accident or natural event that causes significant loss of life and extensive damage to property. Hurricanes, earthquakes, tornadoes, fires, and floods are common natural disasters, while events like the sinking of the Titanic and the April 2010 BP oil well explosion are notable accidents with disastrous outcomes. Some disasters, such as plane crashes, have localized impacts, affecting a small number of people intensely. In contrast, others like hurricanes and earthquakes have widespread effects, impacting a larger geographical area and population. While some sociologists investigate the causes of disasters, others focus on the study of collective behavior during and after these events, known as disaster behavior. Disasters disrupt people’s daily lives and routines, leading to significant changes. As noted by David L. Miller, disasters often strike without warning, and when they do, people face unexpected and unfamiliar problems that demand direct and prompt action. There is the obvious problem of sheer survival at the moment when disaster strikes. During impact, individuals must confront and cope with their fears while at the same time looking to their own and others’ safety. After disaster impact, people encounter numerous problems demanding life-and-death decisions as they carry out rescues and aid the injured (2000:250).

In the aftermath of a disaster, people undergo a period of adjustment lasting days, weeks, and sometimes months as they strive to return to normalcy. Amidst this process, how do individuals typically behave? Following a disaster, it’s often believed that individuals tend to prioritize their own interests, potentially resorting to self-centered and exploitative behavior fueled by panic (Goode 1992). Sociologists studying disaster behavior have found that individuals often exhibit a collective response, engaging in dialogue with others to evaluate the situation, weigh options, and devise solutions together (Goode 1992). Emotional shock is relatively uncommon, as individuals, including strangers, extend support and demonstrate a significant level of concern and generosity towards those affected (Miller 2000). While feelings of grief and depression may arise, they are typically no more severe than those experienced after the loss of loved ones under ordinary circumstances.

Rumors, mass hysteria, and moral panics

The collective behaviors we’ve explored—crowds, riots, and disaster behavior—typically entail physical interaction among individuals. However, other forms of collective behavior involve widely dispersed groups who don’t necessarily interact but share common beliefs and perceptions. Sociologists categorize these phenomena into two main groups: (a) rumors, mass hysteria, and moral panics; and (b) fads and crazes.

Rumors, mass hysteria, and moral panics all involve strongly held beliefs and perceptions that are often untrue or distorted versions of reality. A rumor typically originates from unreliable sources and spreads from person to person, often resulting in false or exaggerated information. The key characteristic of a rumor is its lack of reliable evidence when it first emerges, making it unsubstantiated (Goode 1992). In today’s digital era, rumors can spread rapidly through platforms like the Internet, Facebook, Twitter, and other social media channels. For instance, in October 2010, a baseless rumor circulated that Apple was planning to acquire Sony, causing an increase in Sony’s stock shares despite the rumor’s lack of truth (Albanesius 2010).

Mass hysteria is when there is widespread, intense fear of a danger that later proves to be false or greatly exaggerated. It’s not very common, but one well-known example is the “War of the Worlds” episode (Miller 2000). In 1938, Orson Welles aired a radio adaptation of the H.G. Wells story about Martians invading Earth. Many listeners in New Jersey and New York believed the invasion was real and panicked. Despite reports of stampedes and other extreme reactions the next day, these turned out to be untrue.

A moral panic, similar to mass hysteria, occurs when there is widespread alarm about a perceived threat to moral standards, which later turns out to be untrue or greatly exaggerated. This usually happens concerning issues like drug use or sexual activity. These concerns may lack evidence or greatly amplify the actual danger posed by the behavior. Nevertheless, people’s strong moral beliefs about the situation heighten their worry, often leading them to advocate for laws or take other actions to combat the perceived moral problem.

Goode and Nachman Ben-Yehuda (2009) documented various moral panics in American history. One significant instance was the Prohibition movement of the early 20th century, driven by concerns about alcohol consumption. Led mainly by rural Protestants, who viewed drinking as a moral and social wrongdoing, the movement targeted urban areas, particularly those with large Catholic Irish and Italian immigrant populations. The immigrant status and Catholic faith of these urban residents intensified the activists’ condemnation of their alcohol consumption.

In the 1930s, another moral panic emerged surrounding marijuana, leading to its prohibition. Previously legal, marijuana came under scrutiny due to concerns among Anglo Americans about its use among Mexican Americans. Newspapers circulated sensationalized stories about marijuana’s alleged transformation of users into violent criminals. The Federal Bureau of Narcotics contributed to the hysteria by disseminating misleading information to the media.

These instances highlight how moral panics often target marginalized social groups, such as the poor, people of color, and religious minorities. Pre-existing prejudices against these groups amplify the intensity of moral panics, which, in turn, perpetuate and exacerbate societal biases.

Fads and crazes

Fads and crazes represent a significant aspect of collective behavior. A fad refers to a short-lived trend or product, while a craze captures the temporary obsession of a small group (Goode 1992). Throughout American history, various fads and crazes have emerged, such as goldfish swallowing, telephone booth stuffing, and streaking. Examples of fad products include Rubik’s Cube, Pet Rocks, Cabbage Patch dolls, and Beanie Babies. Initially, cell phones were considered a fad, but their widespread adoption and importance have elevated them beyond that classification. Social media plays a significant role in amplifying and spreading fads and crazes by providing platforms for rapid dissemination of trends, fostering a sense of belonging and social validation among participants, and facilitating viral sharing of content that captures widespread attention. The immediacy and reach of social media platforms enable fads and crazes to gain momentum quickly, often resulting in widespread adoption and cultural impact within a short period.

Explaining Collective Behavior

Over time, sociologists and scholars have put forth numerous theories to explain collective behavior. The majority of these theories concentrate on phenomena like crowds, riots, and social movements, rather than on less interactive behaviors such as rumors and fads. Table 16. “Collective behavior theory snapshot,” provides a summary of these explanations.

Table 16. Collective behavior theory snapshot

|

Theory |

Major Assumptions |

|---|---|

| Contagion theory | Collective behavior arises from the emotional and irrational influence of the crowd. |

| Convergence theory | Crowd behavior mirrors the beliefs and intentions individuals hold before joining the crowd. |

| Emergent norm theory | When people begin interacting in groups, they may feel unsure about how to behave. Through discussion, norms emerge, guiding their actions with social order and rationality. |

| Value-added theory | Collective behavior arises when specific conditions are met, including structural strain, shared beliefs, triggering events, and a lack of social regulation. |

Source: University of Minnesota Libraries. 2016. Social Problems: Continuity and Change. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Libraries Publishing.

Contagion theory

Contagion theory, introduced by French scholar Gustave Le Bon (1841–1931) in his book, The Crowd: A Study of the Popular Mind (Le Bon 1982), emerged in response to concerns about social disorder following the French Revolution and prevalent mob violence during the 19th century in Europe and the United States. Intellectuals, often residing in affluent conditions, perceived this violence as irrational and attributed it to the sway of intense emotions and peer influence within mobs.

Le Bon’s contagion theory, outlined in his book, mirrored these concerns. It posited that individuals, when part of a crowd, succumb to a nearly hypnotic influence, acting irrationally and emotionally, unable to control their instincts. This theory suggests that collective behavior stems from the contagious sway of crowds, leading individuals to behave in ways they wouldn’t when alone. Contagion theory was widely accepted until the 20th century. However, scholars began to realize that collective behavior is more rational than previously thought by Le Bon. Additionally, they found that individuals are not as heavily influenced by crowd dynamics as Le Bon proposed.

Convergence theory

Convergence theory offers a fresh perspective on collective behavior. It suggests that crowds are not solely responsible for provoking individuals into emotional or violent actions. Instead, crowd behavior mirrors the attitudes and actions of the individuals comprising it. When like-minded individuals gather in a crowd, their collective behavior reflects their shared beliefs and intentions. In essence, rather than being influenced by the crowd, individuals shape the behavior of the crowd through their own attitudes and actions. This theory aligns with the idea that individuals with similar beliefs tend to gravitate towards one another, forming crowds that embody their collective values and objectives. As Goode (1992:58) explains,

convergence theory says that the way people act in crowds or publics is an expression or outgrowth of who they are ordinarily. It argues that like-minded people come together in, or converge on, a certain location where collective behavior can and will take place, where individuals can act out tendencies or traits they had in the first place (emphasis in original).

Convergence theory acknowledges that individuals in a crowd may behave differently than they would alone, but it asserts that the collective actions of a crowd mainly stem from the characteristics of its members. For instance, consider a hate crime like gay bashing perpetrated by a small group or mob. This scenario aligns with convergence theory as the individuals involved share a common hatred towards homosexuality and individuals who identify as gay or lesbian. Consequently, the violence enacted by the group mirrors the beliefs held by its members.

Emergent norm theory

In the mid-20th century, Ralph H. Turner and Lewis M. Killian (1957) introduced their emergent norm theory of collective behavior, which offered a different perspective from earlier theories like Le Bon’s emphasis on irrationality. According to Turner and Killian, when people engage in collective behavior, they initially lack clear guidelines for how to act. Through discussion, norms governing behavior emerge, leading to social order and rationality guiding their actions.

Emergent norm theory strikes a balance between contagion theory and convergence theory in two keyways. It views collective behavior as more rational than contagion theory does. However, it also acknowledges that collective behavior is less predictable than convergence theory suggests, as it assumes individuals may not necessarily share beliefs and intentions before joining a group.

Value-added theory

Neil Smelser’s (1963) value-added theory, also known as structural-strain theory, is a key explanation for social movements and collective behavior. According to Smelser, these phenomena emerge under specific conditions. Structural strain, which refers to societal problems causing anger and frustration, is one such condition. Without this strain, there’s no impetus for protest or movement formation. Another condition is generalized beliefs, which are people’s perceptions of the causes of societal issues and their potential solutions. If individuals attribute problems to themselves or believe protest won’t effect change, they’re less likely to mobilize. Additionally, precipitating factors—sudden events like unjust arrests—can trigger collective action, as seen in urban riots of the 1960s. Lack of social control, where participants don’t fear punishment, also fosters collective behavior. While Smelser’s theory identifies crucial conditions for collective action, it’s criticized for its vagueness, particularly regarding the threshold of societal strain needed to spur movement formation (Rule 1988).

Understanding Social Movements

Social movements are powerful drivers of social change globally. However, they frequently encounter resistance from governments and other adversaries. Understanding the origins, successes, failures, and impacts of these movements is essential to comprehending the dynamics of social change.

To grasp the concept of social movements, it’s vital to define them. As stated, a social movement is a coordinated effort by many individuals aimed at promoting or hindering social, political, economic, or cultural transformation. While social movements share similarities with special-interest groups, their methods set them apart. Special-interest groups typically operate within established systems through conventional political tactics like lobbying and campaigning. In contrast, social movements often operate outside established systems, employing tactics such as protests, picket lines, sit-ins, and occasionally, violent actions.

Conceived in this manner, social movements operate as a form of “politics by other means.” These “other means” become necessary because movements lack the resources and access to the political system typically enjoyed by interest groups (Gamson 1990).

Types of social movements

Sociologists categorize social movements based on the type and scope of change they aim for. This classification system helps us distinguish between various social movements from the past and present (Snow and Soule 2009).

One prevalent type of social movement is the reform movement, which seeks specific but significant changes within a nation’s political, economic, or social systems. Unlike revolutionary movements, reform movements do not aim to overthrow the existing government but instead focus on improving conditions within the current framework. Many influential social movements in U.S. history fall into this category, such as the abolitionist movement before the Civil War, the women’s suffrage movement after the Civil War, the labor movement, the Southern civil rights movement, the antiwar movement during the Vietnam era, the contemporary women’s movement, the gay rights movement, and the environmental movement.

A revolutionary movement aims to completely replace the current government and transform society, going beyond mere reforms. Historically, revolutionary movements have sparked major upheavals such as the revolutions in Russia, China, and other countries. Unlike reform movements that seek gradual changes, revolutionary movements seek to establish not only a new government but also a different way of life. Both reform and revolutionary movements are often categorized as political movements due to their focus on political change.

Similarly, reactionary movements oppose or attempt to reverse social changes. An example is the antiabortion movement in the United States, which emerged following the legalization of most abortions in Roe v. Wade (1973). This movement seeks to restrict or abolish abortion rights.

Two additional types of movements are self-help and religious movements. Self-help movements involve individuals seeking to enhance various aspects of their personal lives. Examples of self-help groups include Alcoholics Anonymous and Weight Watchers. Religious movements, on the other hand, focus on reinforcing religious beliefs within their members and spreading these beliefs to others. Early Christianity serves as a significant example of a religious movement, while contemporary religious cults are part of this broader phenomenon. Occasionally, self-help and religious movements overlap, especially when self-help groups emphasize religious faith as a means of personal growth.

Origins of social movements

To grasp how social movements begin, we must address two key questions. Firstly, what societal, cultural, and other elements contribute to their emergence? Social movements don’t appear out of nowhere; they stem from dissatisfaction within society. Secondly, once these movements start, why do certain individuals engage in them more readily than others?

Discontent with existing conditions and relative deprivation

Social movements emerge when people are spurred by existing political, economic, or other issues that ignite dissatisfaction and prompt collective action. These issues may stem from a struggling economy, restricted political freedoms, unfavorable government foreign policies, or various forms of discrimination based on factors like gender, race, ethnicity, or sexual orientation. This aligns with Smelser’s value-added theory, which emphasizes structural strain as a catalyst for collective behavior. Without such strain, characterized by societal problems that evoke anger and frustration, there would be little incentive for protest or the formation of social movements.

Dissatisfaction, regardless of its source, can lead to shared discontent among a population, which may spark a social movement. This discontent often arises from a sense of relative deprivation, where individuals feel they lack compared to others or an ideal state they aspire to reach. James C. Davies (1962) and Ted Robert Gurr (1970) popularized the concept of relative deprivation’s significance in social protest, building upon earlier research on frustration and aggression by social psychologists. Davies proposed that when a deprived group perceives improving social conditions, they feel hopeful about their lives. However, if these conditions stagnate, frustration mounts, potentially leading to protest or collective violence. Both Davies and Gurr stressed that feelings of relative deprivation were more influential in driving collective behavior than actual deprivation levels.

Initially popular, relative deprivation theory suggests that frustration resulting from perceived deprivation may lead to protest. However, scholars have noted that individuals may not always express their frustration through protest; some may internalize blame instead (Gurney and Tierney 1982). Proponents of the theory argue that participation in social movements is often linked to feelings of deprivation. Despite this, many individuals who feel deprived may still choose not to participate in protests (Snow and Oliver 1995).

While discontent is often a precursor to social movements and political collective actions like riots, it doesn’t invariably trigger such events. For instance, although one might assume that a prison riot erupts due to dire prison conditions, some poorly maintained prisons don’t witness such outbreaks. Therefore, while discontent lays the groundwork for social movements and collective behavior, it alone doesn’t ensure the initiation or participation of discontented individuals in such movements.

A well-known study from the 1980s highlights this important concept within social movements (Klandermans and Oegema 1987). Conducted in the Netherlands, the study focused on the peace movement’s efforts to oppose the deployment of cruise missiles. In a town near Amsterdam, approximately 75% of residents expressed opposition to the deployment according to a survey. However, only around 5% of these residents participated in a protest organized by the peace movement against the deployment. This significant difference between the number of residents who sympathized with the movement’s cause and those who actively participated in protests underscores the substantial gap between potential sympathizers and actual activists within social movements.

Social networks and recruitment

The significant decrease in involvement from sympathizers to activists highlights a key aspect of social movement research, individuals are more likely to engage in movement activities when encouraged by friends, acquaintances, or family members. As noted by David S. Meyer (2007: 47), “[T]he best predictor of why anyone takes on any political action is whether that person has been asked to do so. Issues do not automatically drive people into the streets.” Having concerns about issues is not typically enough to motivate people to act. Social movement participants tend to have extensive social networks and affiliations with various organizations, which play a crucial role in recruiting them into movements. This recruitment process is vital for the success of social movements, as they rely on recruiting enough people to thrive. In today’s world, electronic methods are increasingly used to recruit and organize people for social movements.

Resource mobilization and political opportunities

Resource mobilization theory, originating in the 1970s, encompasses various perspectives on social movements (McCarthy and Zald 1977; Oberschall 1973; Tilly 1978). This theory posits that social movement activity arises as a rational response to societal dissatisfaction. While discontent with prevailing conditions is perpetual, actual protests are infrequent. Therefore, the theory suggests that it’s not just the presence of discontent, but the strategic efforts of movement leaders to mobilize resources—such as time, money, and energy—from the population, directing them towards effective political action, that are crucial.

Resource mobilization theory, originating in the 1970s, has been highly influential. However, critics argue that it overlooks the significance of harsh social conditions and discontent in driving social movements. When conditions deteriorate, people are spurred to collective action. For instance, reductions in higher education funding and steep tuition hikes led to widespread student protests across California and other states in late 2009 and early 2010 (Rosenhall 2010). Critics also contend that resource mobilization theory fails to acknowledge the role of emotions in social movements, portraying activists as detached and rational (Goodwin et al. 2004). They argue that this depiction is inaccurate, asserting that social movement participants can be both emotional and rational simultaneously, akin to individuals in various other pursuits.

Another significant viewpoint is political opportunity theory, which suggests that social movements are more likely to emerge and succeed when there are favorable political conditions. For example, when a repressive government transitions to democracy or when a government faces instability due to economic or foreign crises (Snow and Soule, 2010). In such situations, discontented individuals perceive a higher likelihood of success if they engage in political action, motivating them to do so. As Snow and Soule (2010: 66) elaborate, “Whether individuals will act collectively to address their grievances depends in part on whether they have the political opportunity to do so.” Applying this perspective, one reason social movements are more prevalent in democracies compared to authoritarian regimes is that activists feel more liberated to engage in activism without fear of government repression like arbitrary arrests or violence.

Life cycle of social movements

Various social movements worldwide, although diverse in nature, typically follow a recognized life cycle comprising distinct stages, as identified by Blumer (1969).

Stage 1 marks the emergence of a social movement, triggered by various reasons outlined earlier.

In Stage 2, known as coalescence, movement leaders strategize recruitment and plan tactics to achieve their objectives. Utilizing the media for positive coverage becomes crucial in garnering public support.

At Stage 3, institutionalization occurs, leading to bureaucratization. Paid leaders and staff often replace volunteers, establishing clear hierarchies and emphasizing fundraising. However, as movements bureaucratize, they may shift towards conventional methods, potentially diminishing their earlier disruptive impact (Piven and Cloward 1979). Yet, failing to bureaucratize can result in loss of focus and insufficient funding for sustained activity.

Stage 4 marks the decline of a social movement, which can happen for various reasons. Some movements accomplish their objectives and naturally wind down. However, many decline due to failure. Factors like financial constraints, waning enthusiasm among members, and internal divisions can contribute to this decline.

Government actions can influence the decline of a social movement. One way is through “co-optation,” where the government offers small concessions to appease activists without addressing underlying issues. This can reduce discontent but maintain the original problems that sparked the movement. Additionally, repression by authoritarian governments, such as arbitrary arrests or violence against protesters, can suppress movements (Earl 2006). Even in democratic systems, arrests and legal actions against activists can impose financial burdens and deter others from joining protests. For instance, during the Southern civil rights movement, while police violence garnered sympathy, mass arrests served to quell dissent without sparking national outrage (Barkan 1985).

Social movements making a difference

Social movements typically function outside the political system through various forms of protest. Rallies, demonstrations, sit-ins, and silent vigils draw significant attention, especially when covered by the news media. This attention focuses on the core issue or grievance, exerting pressure on governments, corporations, or other entities targeted by the protest.

Throughout U.S. history, social movements have sparked significant changes (Amenta et al. 2010; Meyer 2007; Piven 2006). For instance, the abolitionist movement highlighted the atrocities of slavery, leading to increased public condemnation. Following the Civil War, the women’s suffrage movement secured women’s voting rights with the 19th Amendment in 1920. Similarly, the labor movement of the late 19th and early 20th centuries established crucial labor rights like the minimum wage and the 40-hour workweek. The civil rights movement of the 1950s and 1960s ended legal segregation in the South, while the Vietnam antiwar movement of the 1960s and 1970s contributed to public opposition to the war. In contemporary times, the women’s and LGBTQ+ rights movements have secured various social rights. Additionally, the environmental movement has advocated for legislation to mitigate pollution in air, water, and land.

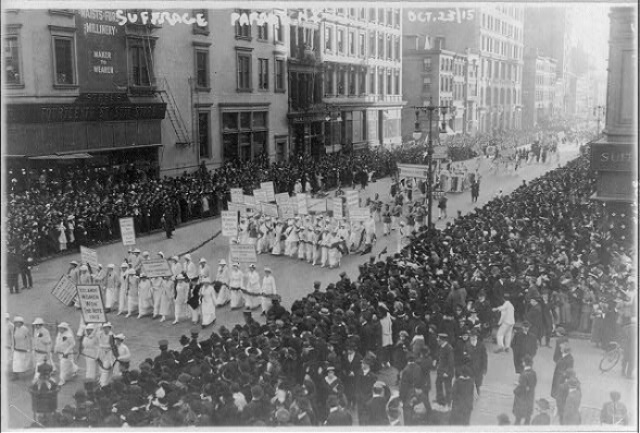

Pre-election suffrage pararde, New York City, October 23, 1915. 20,000 women marched.

While it’s clear that social movements have had a significant impact, until recently, scholars studying social movements have primarily focused on their origins rather than their outcomes (Giugni 2008). However, recent research has started to address this gap by examining the effects of social movements on different areas. These include their political impact on the political system (political consequences), their influence on various aspects of society’s culture (cultural consequences), and the effects they have on the individuals involved in the movements (biographical consequences).

Scholars have examined the political impact of social movements, considering factors such as the effectiveness of protest intensity and issue focus. Research suggests that movements employing higher levels of protest and concentrating on a single issue tend to be more successful. Additionally, movements are often more likely to succeed when protesting against a weakened government facing economic or other challenges. Furthermore, there is debate among movement scholars regarding the organizational structure of movements. Some argue for centralized, bureaucratic organizations, while others advocate for decentralized structures, which may facilitate greater protest engagement (Piven and Cloward 1979; Gamson 1990).

In terms of cultural impact, movements can unintentionally influence various aspects of a society’s culture (Earl 2004). As one scholar noted, the ability to shape the broader cultural landscape might be where movements leave their most profound and enduring mark (Giugni 2008: 1591). Social movements have the power to shape values, beliefs, and cultural practices like music, literature, and fashion.

Engaging in social movements during adolescence and early adulthood can have lasting effects on individuals. Research suggests that participation in such movements can lead to significant personal transformation. Individuals often experience shifts in their political beliefs, which may become more firmly established or altered altogether. Moreover, they are more inclined to remain politically engaged and pursue careers related to social change. As one scholar notes, even minimal involvement in social movement activities can leave a lasting impact on individuals throughout their lives (Giugni 2008: 1590).

In the subsequent sections of the module, we will explore initiatives and societal transformations influenced by public policy and grassroots movements to reduce inequalities.

Reducing Racial & Ethnic Inequality

After exploring race and ethnicity in the United States, what conclusions can we draw about our current situation in the second decade of the twenty-first century? Did Barack Obama’s historic election as president in 2008 mark a turning point towards racial equality, as some suggested, or did it happen despite ongoing racial and ethnic disparities?

There are reasons for optimism. Legal segregation is no longer in place, and the blatant racism of the past has significantly diminished since the 1960s. People of color have achieved notable advancements in various areas of life, and individuals from these communities now hold significant elected positions both within and beyond the South, a development unimaginable just a generation ago. Notably, Barack Obama, with African ancestry, self-identifies as African American, and his election in 2008 was celebrated nationwide for its symbolic significance. Undoubtedly, progress has occurred in racial and ethnic relations in the United States.

However, there is also reason for concern. Traditional racism has evolved into a modern form of symbolic racism, which still holds people of color responsible for their difficulties and undermines public support for government interventions to address their challenges. Institutional discrimination persists, along with hate crimes like the cross burning mentioned earlier. Suspicion toward individuals based solely on their skin color remains prevalent, as highlighted by incidents such as the Trayvon Martin tragedy.

Despite these challenges, there are several promising programs and policies that, if properly funded and implemented, could effectively reduce racial and ethnic inequalities. We will explore these shortly, but first, let’s address affirmative action, a topic that has sparked controversy since its inception.

Affirmative action

Affirmative action involves giving special consideration to minorities and women in employment and education to address the discrimination and lack of opportunities they face. Originating in the 1960s, these programs aimed to provide African Americans initially, and later, other people of color and women, with access to jobs and education to offset past discrimination. President John F. Kennedy first used the term in 1961 when he issued an executive order mandating federal contractors to take affirmative action in hiring without regard to race and national origin. President Lyndon B. Johnson expanded this to include sex as a demographic category six years later.

While affirmative action programs still exist today, their number and scope have been constrained by court rulings, state laws, and other initiatives. Despite these limitations, affirmative action remains a contentious topic, with scholars, the public, and elected officials holding divergent views on its efficacy and fairness.

One significant court ruling discussed is the U.S. Supreme Court’s decision in Regents of the University of California v. Bakke, 438 US 265 (1978). Allan Bakke, a 35-year-old white applicant, applied twice to the University of California, Davis medical school but was denied admission. UC Davis had a policy of reserving sixteen seats in its class of one hundred for qualified individuals of color to address their underrepresentation in the medical field. Despite Bakke’s higher grades and test scores compared to some admitted applicants of color, he claimed reverse racial discrimination based on his White identity and sued for admission (Stefoff 2005).

The Supreme Court ruled 5–4 that Bakke had to be admitted to UC Davis medical school because he was unfairly rejected due to his race. This decision marked a historic shift away from strict racial quotas in admissions, emphasizing that no applicant should be denied solely based on race. However, the Court also acknowledged that race could be one of many factors considered in admissions, alongside grades and test scores, particularly if a school aims to promote diversity among its student body.

Two recent Supreme Court cases focused on the University of Michigan: Gratz v. Bollinger, which concerned undergraduate admissions, and Grutter v. Bollinger, which addressed law school admissions. In Grutter, the Court upheld the right of colleges to consider race in admissions. However, in Gratz, the Court ruled against the university’s practice of giving extra points to students of color, stating that admissions evaluations should be more personalized than a point system allows. These rulings affirm that affirmative action in higher education admissions based on race/ethnicity is acceptable if it avoids strict quotas and instead uses an individualized assessment approach. Race can be one of several factors considered, but it should not be the sole criterion.

Opponents of affirmative action argue against it for various reasons (Connors 2009). They claim it constitutes reverse discrimination, violating legal and moral principles. They argue that beneficiaries of affirmative action are often less qualified compared to white counterparts competing for jobs and college admissions. Moreover, opponents suggest that affirmative action perpetuates the perception of beneficiaries as less capable, thereby stigmatizing them.

In contrast, proponents of affirmative action offer several justifications in support of it (Connors et al. 2009). They contend that it serves to rectify historical and ongoing discrimination against people of color, addressing disparities in opportunities. For instance, due to social networks, Whites have better access to job opportunities, placing people of color at a disadvantage. Affirmative action is seen as a means to level the playing field in employment. Additionally, proponents argue that affirmative action promotes diversity in workplaces and on campuses, akin to preferences given to out-of-state students or legacy applicants. They argue that considering racial and ethnic backgrounds alongside other criteria helps achieve a diverse student body, aligning with broader goals of inclusivity and equal opportunity.

Supporters argue that affirmative action has successfully broadened employment and educational prospects for people of color. They contend that beneficiaries of affirmative action generally thrive in both the workplace and academic settings. For example, research shows that African American students admitted to selective U.S. colleges and universities under affirmative action are slightly more likely than their white peers to attain professional degrees and engage in civic activities (Bowen and Bok 1998).

Despite these achievements, the debate surrounding affirmative action persists. Critics raise concerns about its fairness and effectiveness. However, proponents advocate for its necessity to address historical and ongoing discrimination, providing opportunities to marginalized communities. Without such programs, the cycle of discrimination and inequality faced by disadvantaged individuals is likely to persist.

Other programs and policies

As highlighted earlier in this module, DNA evidence and evolutionary studies emphasize that we are all members of a single human race. Failing to acknowledge this truth risks repeating historical injustices, where racial and ethnic differences led to discrimination and oppression against non-white communities. In America’s democratic society, it’s imperative to strive for improvement to ensure genuine “liberty and justice for all.”

As the United States strives to address racial and ethnic inequality, sociology highlights the structural roots of this disparity. This perspective underscores that such inequality is less about personal shortcomings of people of color and more about the systemic barriers they encounter, including ongoing discrimination and limited opportunities. Therefore, long-term solutions to reducing racial and ethnic inequality must focus on addressing these structural obstacles (Danziger et al. 2004; Syme 2008; Walsh 2011). Some strategies, similar to those targeting poverty reduction, include:

- Implementing a national “full employment” policy with federally funded job training and public works programs.

- Increasing federal assistance for low-income workers, including earned income credits and child-care subsidies.

- Expanding well-funded early childhood intervention programs and adolescent intervention programs like Upward Bound for low-income teenagers.

- Enhancing the quality of schooling for poor children and expanding early childhood education initiatives.

- Providing improved nutrition and healthcare services for economically disadvantaged families with young children.

- Strengthening efforts to reduce teenage pregnancies.

- Reinforcing affirmative action programs within legal boundaries.

- Enhancing legal enforcement against racial and ethnic discrimination in employment.

- Intensifying efforts to diminish residential segregation.

Reducing Gender Inequality

Gender inequality persists in most societies globally, including the United States. Just as racial and ethnic biases contribute to racial and ethnic inequality, gender stereotypes and false beliefs perpetuate gender inequality. While these stereotypes have diminished since the 1970s, they still hinder efforts toward achieving full gender equality.

A sociological perspective underscores that gender inequality arises from a complex interplay of cultural and structural factors. Despite progress, traditional gender norms persistently shape socialization from infancy, limiting both girls’ and boys’ potential. Structural barriers in workplaces and other spheres further maintain women’s subordinate social and economic status relative to men. Efforts to reduce gender inequality must address both cultural and structural dimensions to build on the progress made since the 1970s.

To address gender inequality, sociological insights recommend implementing various policies and measures targeting the cultural and structural factors contributing to this issue. These actions may encompass:

- Reducing the influence of parental and societal gender socialization on children.

- Challenging gender stereotypes perpetuated by the media.

- Raising public awareness about the causes, prevalence, and consequences of sexual violence, harassment, and pornography.

- Strengthening enforcement of laws against gender-based employment discrimination and sexual harassment.

- Allocating more resources to rape-crisis centers and support services for women who have experienced sexual violence.

- Expanding government funding for high-quality childcare facilities to support parents, particularly mothers, in pursuing employment opportunities without financial or childcare-related constraints.

- Promoting mentorship programs and initiatives to increase female representation in traditionally male-dominated fields and in positions of political leadership.

When discussing ways to address gender inequality, we must recognize the significant impact of the modern women’s movement. Since its inception in the late 1960s, this movement has driven important progress for women across various domains. Courageous individuals challenged societal norms, highlighting gender disparities in workplaces, education, and beyond. They also raised awareness about issues such as rape, sexual assault, harassment, and domestic violence on a national scale. Sustaining momentum in the fight against gender inequality requires ongoing support for a robust women’s movement, which serves as a crucial reminder of the persistent sexism in American society and globally.

Addressing rape and sexual assault

Gender inequality is evident in the prevalence of violence against women. A sociological viewpoint highlights how cultural narratives, economic disparities, and gender inequality contribute to rape, extending beyond individual perpetrators. Addressing this issue requires broader societal changes, challenging beliefs about rape and addressing poverty while empowering women. Randall and Haskell (1995) emphasize the need to question the structural inequalities embedded in our society.

In addition to these fundamental shifts, improving and adequately funding rape-crisis centers is crucial for supporting survivors. However, women of color face further obstacles as many of these centers were established in areas primarily inhabited by white, middle-class individuals, neglecting the needs of women of color in inner cities and Native American reservations. This disparity means that women of color often lack the support available to their white counterparts, highlighting ongoing inequalities despite some progress (Matthews 1989).

Reducing Inequality of Sexualities

The inequality based on sexual orientation stems from longstanding prejudice against non-heterosexual attraction and behavior. However, attitudes towards same-sex sexuality have improved significantly over the past generation. This positive trend is reflected in the increased number of openly gay elected officials and candidates for office. In many parts of the country, a candidate’s sexual orientation is no longer a significant issue. For instance, a Gallup poll conducted in 2011 found that two-thirds of Americans would vote for a gay candidate for president, a sharp increase from just one-fourth in 1978. Additionally, in 2011, the U.S. Senate confirmed the nomination of the first openly gay man for a federal judgeship. These developments suggest progress towards greater acceptance and equality. In summary, as exemplified by a nationwide campaign aimed at supporting gay teens, there is a growing recognition that societal attitudes are improving for non-heterosexual individuals.

Much of the progress in LGBT rights can be attributed to the gay rights movement, widely recognized to have started in June 1969 in New York City following a police raid at the Stonewall Inn, a gay bar, leading to protests and riots. This marked the beginning of the gay rights movement.

While significant strides have been made and public attitudes towards LGBTQ+ issues have improved, this module highlights ongoing inequalities and challenges faced by LGBTQ+ individuals. Similar to efforts to address inequalities based on race, ethnicity, social class, and gender, there remains substantial work to be done to reduce discrimination based on sexual orientation.

To reduce inequality, it’s crucial for heterosexuals to actively avoid mistreating LGBTQ+ individuals and to treat them equally. Additionally, several measures can help address LGBTQ+ inequality, including:

- Encouraging parents to affirm the validity of all sexual orientations to their children, showing equal love and support regardless of sexual orientation.

- Strengthening school programs to create a positive environment for all sexual orientations, educating students about LGBTQ+ issues, and preventing bullying and harassment. States should consider implementing curriculum like California’s requirement to teach gay and lesbian history.

- Enacting federal laws to prohibit employment discrimination against LGBTQ+ individuals and legalizing same-sex marriages nationwide. In the interim, legislation should grant same-sex couples the same rights and benefits as heterosexual married couples.

- Police departments should enhance their understanding of LGBTQ+ issues and ensure that physical attacks against LGBTQ+ individuals are treated with the same seriousness as attacks against heterosexual individuals.

APPLYING A SOCIAL ANALYTIC MINDSET

Exploring Social Movements

Research a current social movement that is addressing one of the social problems or issues we have explored in this book – for example, unions, non-profit organizations, web-based advocacy groups, government programs, churches, schools, etc.

- Choose a social movement related to your topic of choice, and provide information about the group or organization and their movement.

- Describe the social movement or solution. What defines this as a social movement? What is the focused goal of the group? Who participates? Where does their funding come from? Is it local, national, or global?

- Evaluate the effectiveness of the program. Discuss local, national, and global impact. Are they meeting their stated goals?

- Explain the steps you would take to enhance the movement for social change and enhance the well-being of individuals.

“Exploring Social Movements” by Katie Conklin, West Hills College Lemoore is licensed under CC BY 4.0