4.1 Income & Wealth

“Survey: More US Kids Go to School Hungry,” the headline read, revealing the impact of ongoing economic challenges in the United States. A nationwide survey of 638 public school teachers in grades K–8, conducted by Share Our Strength, a nonprofit organization dedicated to combating childhood hunger, unveiled concerning findings. The survey indicated that a significant portion of students arrived at school without having eaten, and more than two-thirds of teachers reporting that some students regularly came to school too hungry to focus on learning, often having missed dinner the night before. Over 60 percent of teachers noted that this issue had worsened in the past year, and over 40 percent labeling it as a “serious” problem. Many teachers admitted to using their own funds to provide food for their students. As one elementary school teacher recounted, “I’ve had numerous students—not just a few—who come to school, put their heads down, and cry because they haven’t eaten since yesterday’s lunch” (United Press International 2011).

While the United States boasts immense wealth, with many Americans enjoying luxury or comfortable lifestyles, the stark reality of childhood hunger serves as a poignant reminder of the prevalent poverty within the nation. This module examines the factors that contribute to poverty, the high poverty rate in the U.S., and the devastating effects on millions living in or near poverty. Additionally, it sheds light on poverty in the world’s poorest nations and discusses initiatives aimed at alleviating poverty both domestically and internationally.

Despite the bleak portrayal of poverty in this module, there remains room for optimism. As demonstrated by the impactful “war on poverty” initiated in the 1960s in the United States, significant strides were made in reducing poverty. This effort was inspired by influential literature such as The Other America: Poverty in the United States by Harrington (1962) and Bagdikian’s (1964) In the Midst of Plenty: The Poor in America (1964). Bagdikian vividly portrays the struggles of the poor, and in response, the federal government implemented various funding programs and policies that significantly reduced the poverty rate in less than a decade (Schwartz 1984). However, since the 1960s and 1970s, the United States has scaled back on these initiatives, resulting in poverty no longer being a priority on the national agenda. In contrast, other affluent democracies allocate more funding and offer more extensive services for their impoverished populations, leading to considerably lower poverty rates compared to the U.S.

Nevertheless, both the history of the war on poverty and the experiences of these other nations illustrate that effective policies and programs can indeed reduce poverty in the United States. By revisiting its past efforts in combating poverty and drawing lessons from other Western democracies, the United States could once again make strides in reducing poverty and improving the lives of millions of Americans.

But why should we even care about poverty? Many politicians and a significant portion of the public tend to blame the poor for their situation, opposing increased federal spending to assist them and even advocating for reductions in such spending. Poverty specialist Mark R. Rank (2011) suggests that we often tend to perceive poverty as a concern that belongs to others. Rank contends that this indifferent outlook is narrow-minded because, as he asserts, “poverty affects us all” (p. 17). He elaborates on this point, highlighting at least two reasons why this is the case.

First, the United States expends a significant amount of resources due to the repercussions of poverty. Individuals facing economic hardship often grapple with deteriorating health, familial challenges, heightened crime rates, and various other issues, all necessitating substantial annual expenditures by the nation. In fact, it has been estimated that childhood poverty alone imposes a staggering $500 billion burden on the U.S. economy each year, stemming from associated problems such as unemployment, low-wage employment, increased crime rates, and both physical and mental health issues (Eckholm 2007). If the poverty rate in the U.S. were on par with that of other democratic nations, substantial tax dollars and other resources could be saved.

Second, a significant portion of the American population is likely to experience poverty or near-poverty at some juncture in their lives. Statistics reveal that approximately 75 percent of individuals aged 20 to 75 will encounter poverty or near-poverty for at least one year within this span of time. As noted by Rank (2011:18), most Americans “will find ourselves below the poverty line and using a social safety net program at some point.” Given the considerable financial toll of poverty on the United States and the widespread prevalence of such experiences, Rank argues that there should be a collective desire for the nation to pursue every avenue possible to mitigate poverty.

Sociologist John Iceland (2006) provides two more compelling reasons why poverty concerns everyone and why its reduction is imperative. To begin, a pervasive poverty rate hinders the economic advancement of our nation with a substantial portion of the population unable to afford essential goods and services, attaining economic growth becomes considerably challenging. Second, poverty generates crime and various other societal issues that impact individuals across all socioeconomic levels. Consequently, alleviating poverty would not only benefit those living in poverty but also extend its positive effects to those who are not economically disadvantaged.

Understanding Poverty

Our exploration of poverty starts with an analysis of how poverty is assessed and the extent to which it prevails. In the 1960s, when U.S. officials began grappling with concerns about poverty, they quickly recognized the necessity of establishing a metric to gauge its extent. This led to the introduction of an official measure of poverty, known as the poverty line. Economist Mollie Orshansky, devised this line in 1963 by multiplying the cost of a very basic diet by three, based on a 1955 government study indicating that the average American family allocated one-third of its income to food. Consequently, a family with a cash income lower than three times the cost of this minimal diet was deemed officially impoverished.

However, this method of determining the poverty line has remained unchanged since 1963, rendering it outdated for several reasons. Modern-day expenses, such as heating, electricity, childcare, transportation, and healthcare, now represent a larger portion of a typical family’s budget than they did in 1963. Moreover, the official measure overlooks noncash income from benefits like food stamps and tax credits. Additionally, as a national metric, the poverty line fails to accommodate regional variations in the cost of living. These shortcomings render the official measurement of poverty highly questionable. As noted by one poverty expert, “The official measure no longer corresponds to reality. It doesn’t get either side of the equation right—how much the poor have or how much they need. No one really trusts the data” (DeParle et al. 2011:A1). We’ll revisit this matter shortly.

The poverty line undergoes annual adjustments for inflation and considers family size. For instance, in 2010, the poverty line for a nonfarm family of four (comprising two adults and two children) stood at $22,213. A family of four earning even a dollar more than $22,213 in 2010 did not fall under the official poverty category, despite their “additional” income barely alleviating their financial situation. Poverty analysts have devised a bare-bones budget to cover essential needs like food, clothing, and shelter, which roughly doubles the poverty line. Families earning between the poverty line and twice that amount, often termed “twice poverty,” struggle to make ends meet but do not meet the official poverty criteria. Thus, when discussing the poverty level here, it’s important to note that we are solely referring to official poverty, while acknowledging numerous families and individuals living near poverty who struggle to meet basic needs, especially when confronted with significant medical or transportation expenses. Consequently, many researchers argue that families require incomes twice as high as the federal poverty level just to manage (Wright et al. 2011). As a result, they rely on twice poverty data (i.e., family incomes below twice the poverty line) to offer a more accurate portrayal of the number of Americans experiencing severe financial hardships, even if they do not technically fall under the official poverty designation.

The scope of poverty

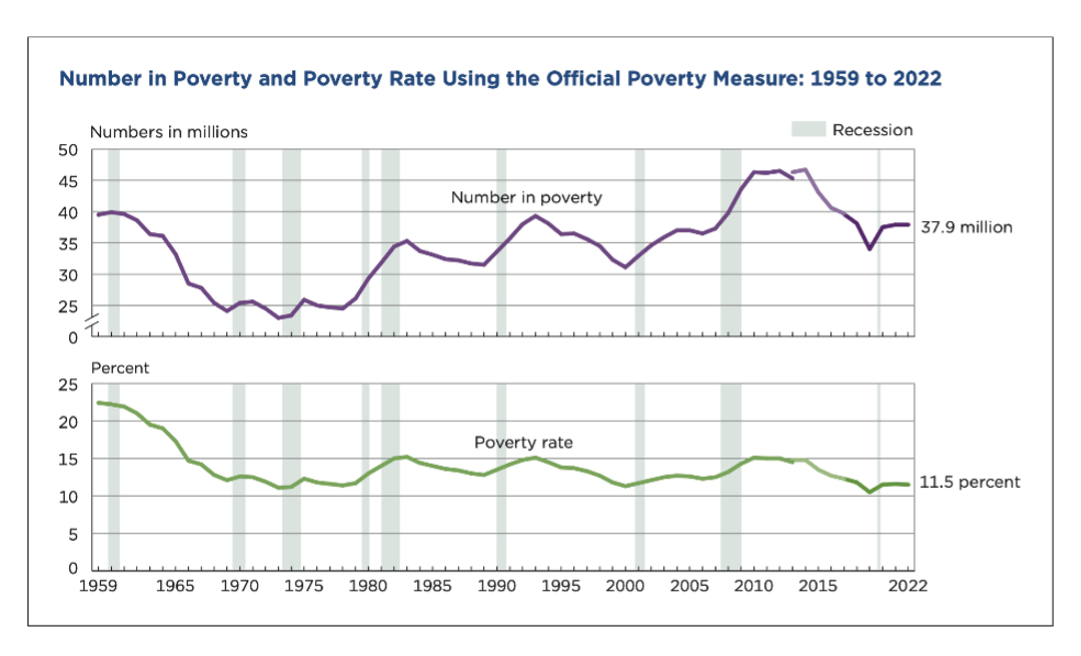

Keeping this caveat in mind, let’s explore the extent of poverty in America. According to the U.S. Census Bureau, using the traditional official poverty measure established in 1963, approximately 15.1 percent of the U.S. population, equivalent to over 35 million individuals, were living below the poverty line in 2010 (DeNavas-Walt et al. 2011). Although this percentage showed a decline from the early 1990s, it remained higher than the rate in 2000 and even surpassed the levels observed in the late 1960s (see Figure 5. “Number in poverty and poverty rate using the official poverty measure: 1959–2022”). While there was a significant reduction in poverty during the 1960s (as evidenced by the sharp decline in Figure 5. “Number in poverty and poverty rate using the official poverty measure: 1959–2022,” progress seems to have stalled since then with poverty rates showing minimal improvement.

Another way to grasp the scale of poverty is by considering episodic poverty, which the Census Bureau defines as experiencing poverty for at least two consecutive months within a specific timeframe. Between 2004 and 2007, nearly one-third of the U.S. population, approximately 95 million individuals, encountered poverty for at least two consecutive months, although only 2.2 percent experienced poverty continuously for all three years (DeNavas-Walt, et al. 2010). These data highlight the dynamic nature of poverty, with individuals transitioning in and out of impoverished circumstances. However, even those who escape poverty typically do not move far from its grasp. Moreover, as previously mentioned, a significant majority of Americans can anticipate facing poverty or near-poverty at some juncture in their lives.

Figure 5. Number in poverty and poverty rate using the official poverty measure: 1959–2022

Recognizing the limitations of the official poverty measure, the Census Bureau has developed a Supplemental Poverty Measure. This measure takes into consideration various family expenses beyond food, accounts for regional differences in the cost of living, factors in taxes paid and tax credits received, and incorporates government assistance programs such as food stamps, Medicaid, and certain other forms of aid. As a result, this updated measure provides a more nuanced estimate of poverty compared to the simplistic official poverty measure, which primarily focuses on family size, food costs, and cash income. According to this revised measure, the poverty rate in 2010 stood at 16.0 percent, equating to 49.1 million Americans (Short 2011). Given that the official poverty measure identified 46.2 million people as poor, the more accurate supplemental measure revealed an increase of nearly 3 million individuals classified as poor in the United States. Without the support of programs like Social Security and food stamps, at least an additional 25 million people would fall below the poverty threshold (Sherman 2011). These programs play a crucial role in keeping many individuals above the poverty line, despite ongoing financial challenges and persistently high poverty rates.

One last statistic deserves attention. Many poverty experts argue that twice-poverty data—reflecting the percentage and number of individuals residing in households with incomes below twice the official poverty threshold—offer a more accurate measure of the true magnitude of poverty, broadly defined, in the United States. By utilizing the twice poverty benchmark, it is estimated that approximately one-third of the U.S. population, exceeding 100 million Americans, either live in poverty or hover dangerously close to it (Center for American Progress 2011). Those teetering on the brink of poverty are merely one crisis away—such as losing a job or experiencing a severe illness or injury—from falling into poverty. The twice poverty data present an exceptionally disheartening outlook.

Social Patterns of Poverty

Who makes up the poor? While the official poverty rate stood at 15.1 percent in 2010, this figure varies significantly based on key sociodemographic factors such as race/ethnicity, gender, and age, as well as by geographic region and family composition. Understanding these variations in poverty rates based on these factors is essential for comprehending the dynamics and social distribution of poverty in the United States. We will examine each of these factors using Census data (DeNavas-Walt et al. 2011).

Race and ethnicity

Let’s try a quick quiz; please select the correct answer.

The majority of poor people in the United States are:

-

- Black/African American

- Latinx/e

- Native American/Indigenous

- Asian/Pacific Islanders

- White

What did you choose? If you’re like most respondents in public opinion surveys, you likely selected option a. Black/African American. When considering impoverished individuals, Americans often envision African Americans (White 2007). This prevalent perception is believed to diminish public empathy towards people in poverty and contribute to resistance against increasing government assistance for the impoverished. Public sentiments on these matters are considered pivotal in shaping government policies on poverty. Therefore, it’s crucial for the public to possess an accurate understanding of the racial and ethnic distribution of poverty.

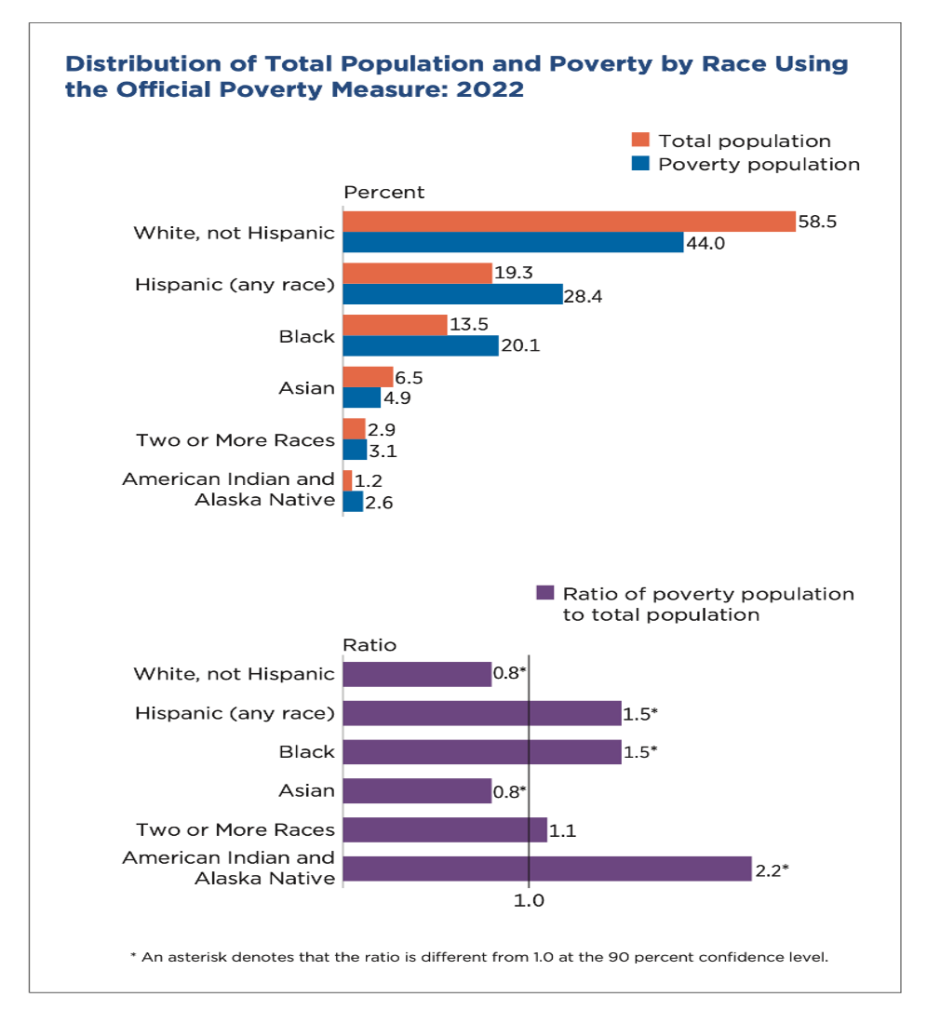

Unfortunately, the public’s perception of the racial demographics of poverty is flawed, as Census data in Figure 6 reveal that the most common demographic among those living in poverty is White (non-Latinx/e). To be specific, 44 percent of individuals in poverty are White (non-Latinx/e), 28.4 percent are Latinx/e, 20 percent are African American, and 4.9 percent are Asian American (refer to Figure 6. “Distribution of total population & poverty by race using the official poverty measure: 2022”). These statistics underscore that non-Latinx/e Whites make up the largest segment of the impoverished population in America.

Figure 6. Distribution of total population & poverty by race using the official poverty measure, 2022

However, it’s important to note that race and ethnicity significantly influence the likelihood of experiencing poverty. While a 08. ratio of non-Latinx/e Whites live below the poverty line; the figures rise to a 1.5 ratio for African Americans and 2.2 for American Indian and Alaska Natives. This means that African Americans and American Indian and Alaska Natives are more likely to be impoverished. Considering the large population of non-Latinx/e whites in the United States, the majority of impoverished individuals are White, even though the percentage of Whites in poverty is comparatively lower. The pronounced disparities in poverty rates among people of different racial and ethnic backgrounds are so noteworthy and impactful that they have been labeled the “colors of poverty” (Lin and Harris 2008).

Gender

Many women are familiar with the unfortunate reality that they are more likely to experience poverty compared to men. Census data reveals that 16.2 percent of females live below the poverty line, whereas only 14.0 percent of males do. This means there is a significant gender disparity in poverty rates, with 25.2 million women and girls living in poverty, compared to 21.0 million men and boys, marking a difference of 4.2 million individuals. This phenomenon, known as the feminization of poverty, is extensively discussed by Iceland (2006).

Age

When we consider age, it’s evident that a significant portion of children under 18 experience poverty, with 22 percent, totaling 16.4 million children, living below the poverty line. This percentage is notably higher for African American and Latinx/e children, at around 39 percent and 35 percent respectively. Additionally, about 37 percent of all children will encounter poverty at some point before reaching adulthood, as highlighted by Ratcliffe and McKernan (2010). The United States’ childhood poverty rate is strikingly high compared to other affluent democracies, being 1.5 to 9 times greater than rates in Canada and Western Europe, as noted by Mishel et al. (2009). Looking specifically at families with incomes below twice the official poverty level, referred to as low-income families, we find that nearly 44 percent of American children, approximately 32.5 million, belong to such households and are commonly referenced as low-income children, with a disproportionately high number being African American and Latinx/e children.

Shifting the focus to older individuals, approximately 9 percent of those aged 65 or older are living in poverty, totaling around 3.5 million seniors. However, when we analyze these age demographics, we find that nearly 36 percent of all poor individuals in the United States are children, while nearly 8 percent are 65 or older. This means that more than 43.4 percent of Americans living in poverty are either children or elderly individuals.

Region

Poverty rates vary across the United States, with some states and counties experiencing higher levels of poverty than others. One way to grasp these geographical differences is by examining poverty rates across the nation’s four major regions. The South emerges as the region with the highest poverty rate, standing at 16.9 percent, followed by the West (15.3 percent), the Midwest (13.9 percent), and finally the Northeast (12.8 percent). The elevated poverty rate in the South is believed to contribute significantly to the region’s higher incidence of illnesses and health issues compared to other regions, as discussed by Ramshaw (2013).

Family structure

Various family structures exist, including those where a married couple resides with their children, an unmarried couple cohabitates with one or more children, a household with children led by a single parent (typically a woman), a household comprising two adults without children, and a household where a single adult lives independently. Poverty rates across the nation vary depending on the family structure.

As expected, poverty rates tend to be higher in single-adult households compared to those with two adults, largely because dual-income households are more common. Additionally, within single-adult households, poverty rates are higher in those led by a woman than in those led by a man, as women typically earn lower incomes than men. Specifically, 31.6 percent of families led by a single woman live in poverty, whereas only 15.8 percent of families led by a single man do. In contrast, a mere 6.2 percent of families led by a married couple experience poverty. The elevated poverty rate among female-headed families further substantiates the notion of the feminization of poverty discussed earlier.

As discussed earlier, a notable 22 percent of American children experience poverty. However, this percentage significantly fluctuates depending on the family structure they belong to. For instance, only 11.6 percent of children living with married parents are classified as poor, contrasting sharply with the 46.9 percent of those residing solely with their mother. This latter percentage further escalates to 53.3 percent for African American children and 57.0 percent for Latinx/e children, as reported by the U.S. Census Bureau (2012). Regardless of racial or ethnic background, children living with only their mothers face particularly heightened risks of poverty.

Labor force status

According to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (2024), approximately 6.1 million people are without jobs. The rates across different demographic groups, such as adult men, women, teenagers, Whites, African Americans, Asian Americans, and Latinx/e Americans, saw little to no change.

About 1.3 million individuals had been unemployed for 27 weeks or more, constituting around 20.8 percent of the total unemployed population. The labor force participation rate stayed steady at 62.5 percent, and the employment-population ratio barely changed at 60.2 percent, showing minimal fluctuations throughout the year.

In terms of part-time employment due to economic reasons, approximately 4.4 million individuals saw little change. These individuals were working part-time either because their hours were reduced or they couldn’t secure full-time positions.

The number of individuals not actively participating in the labor force but desiring employment, totaling 5.8 million, remain relatively stable. These individuals weren’t classified as unemployed because they hadn’t actively sought work in the past four weeks or weren’t available for employment.

Among those outside the labor force yet seeking employment, approximately 1.7 million were marginally attached to the workforce. These individuals were willing and able to work, having searched for employment within the past year but not in the past month. The number of discouraged workers, a subgroup of the marginally attached who believed no job opportunities were available to them, rose to 452,000.

FEEDING MOTEL KIDS

In Anaheim, California, just a short distance from Disneyland, over 1,000 families are residing in budget motels, often used by individuals involved in illicit activities such as drug dealing and prostitution. These families are unable to afford the upfront costs required for renting an apartment, leaving them with no alternative but to stay in these motels to avoid homelessness. As highlighted by Bruno Serato, a local restaurant owner, “Some people are stuck, they have no money. They need to live in that room. They’ve lost everything they have. They have no other choice. No choice.”

Serato became aware of these families in 2005 when he encountered a young boy at the local Boys & Girls Club who was eating a bag of potato chips for dinner. Learning that the boy and his family were living in a motel, Serato discovered that the Boys & Girls Club had initiated a program to assist these “motel kids” by providing transportation from school to their motels. Despite receiving free breakfast and lunch at school, many of these children were still experiencing hunger in the evenings. In response, Serato began serving pasta dinners to around seventy children at the club each night, a number that grew to almost three hundred children by spring 2011. Serato covers the costs of food and transportation, amounting to approximately $2,000 per month, and estimates that his program has provided over 300,000 pasta dinners to motel kids by 2011.

Carlos and Anthony Gomez, aged 12, along with their family, who live in a motel room, are among those who benefit from Serato’s pasta dinners. Their father expressed gratitude for the meals, stating “I no longer worry as much, about them [coming home] and there being no food. I know that they eat over there at [the] Boys & Girls Club.”

Bruno Serato is simply delighted to lend a hand. “They’re like customers,” he elaborates, “but they’re my favorite customers” (Toner 2011).

Serato’s charitable efforts have been documented in various media outlets, and further information can be found on his charity’s website at www.thecaterinasclub.org.

Toner, Kathleen. 2011. “Making Sure ‘Motel Kids’ Don’t Go Hungry.” CNN. Retrieved from (http://www.cnn.com/2011/LIVING/03/24/cnnheroes.serato.motel.kids/index.html).

Explaining Poverty

The question of why poverty exists and how individuals become impoverished is a central concern in sociology. Module 1 “The Importance of a Social Analytic Mind” introduces various sociological perspectives that offer insights into these questions by examining the structure of American society and its stratification, which encompasses a spectrum of wealth from the very affluent to the extremely poor. Before turning to explanations specific to poverty, it is important to grasp the broader views on social stratification presented in this module.

Generally, the functionalist and conflict perspectives seek to explain the origins and persistence of social stratification, while the symbolic interactionist perspective explores how such stratification shapes interpersonal dynamics in daily life. Table 10. “Theory snapshot on stratification,” provides a concise overview of these three approaches.

Table 10. Theory snapshot on stratification

|

Theoretical Perspective |

Major Assumptions |

|---|---|

| Functionalism | Stratification is necessary to induce people with special intelligence, knowledge, and skills to enter the most important occupations. For this reason, stratification is necessary and inevitable. |

| Conflict theory | Stratification results from lack of opportunity and from discrimination and prejudice against the poor, women, and people of color. It is neither necessary nor inevitable. |

| Symbolic interactionism | Stratification affects people’s beliefs, lifestyles, daily interaction, and conceptions of themselves. |

Source: University of Minnesota Libraries. 2016. Social Problems: Continuity and Change. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Libraries Publishing.

The functionalist perspective

In Module 1 “The Importance of a Social Analytic Mind” we discussed the functionalist theory, which suggests that societal structures and processes exist because they serve vital functions for the stability and continuity of society. Within this framework, functionalist sociologists assume that stratification exists because it fulfills important functions for society. This perspective was initially articulated over sixty years ago by Kingsley Davis and Wilbert Moore (1945) and their theory is grounded in several logical assumptions, positing that social stratification is both essential and unavoidable. When applied to American society, these assumptions can be summarized as follows:

-

- Certain occupations hold more significance than others. For instance, brain surgery is deemed more critical than shoe shining.

- Certain occupations demand a greater level of expertise and knowledge than others. Following the example above, brain surgery requires more specialized skills and education compared to shoe shining.

- Few individuals possess the aptitude to acquire the necessary skills and knowledge for these critical and highly specialized roles. While many of us could proficiently shine shoes, only a select few could ever aspire to become brain surgeons.

- To incentivize individuals to pursue these crucial, highly skilled occupations, society offers them higher incomes or other rewards. Consequently, certain individuals ascend higher in society’s hierarchy, leading to the inevitability of social stratification.

To illustrate these assumptions, let’s imagine a society where both shining shoes and performing brain surgery yield annual incomes of $150,000. While this scenario is purely hypothetical, it helps to demonstrate the following concept. If one opts for shining shoes, they can start earning this income at the age of 16. However, if they choose to pursue a career in brain surgery, they won’t reach the same income level until around the age of 35. This is because they must first complete college and medical school, followed by several more years of medical training. While dedicating nineteen additional years beyond the age of 16 to education and training, along with taking on significant student loan debt, one could have potentially earned $150,000 a year by shining shoes, amounting to a total of $2.85 million over those years. This prompts the question: which profession would you choose?

This example suggests that many individuals may not opt for careers such as brain surgery unless significant financial and other incentives are guaranteed. Consequently, society might face a shortage of individuals willing to undertake crucial roles unless similar rewards are assured. This leads to the necessity of stratification. With stratification comes the reality that some individuals will possess considerably less wealth than others. If stratification is deemed unavoidable, then poverty becomes an inevitable outcome. The functionalist perspective further implies that individuals experiencing poverty do so because they lack the capacity to attain the skills and knowledge required for high-paying, essential occupations.

While the functionalist perspective may initially appear logical, several years following the publication of Davis and Moore’s theory, other sociologists highlighted significant flaws in their argument (Tumin 1953; Wrong 1959). First, comparing the significance of various types of jobs poses a challenge. For instance, consider the comparison between brain surgery and coal mining. While brain surgery may seem more crucial at first glance, society heavily relies on coal mining for its functioning. Similarly, when pondering the importance of professions like attorney and professor, one must be cautious in their assessment. Both roles play essential roles in society, each contributing in distinct yet valuable ways.

Second, the functionalist perspective suggests that the most critical roles in society command the highest salaries, while less crucial roles receive lower incomes. However, various examples, as highlighted earlier, challenge this notion. For example, coal miners typically earn considerably less than physicians, and professors generally have lower average earnings compared to lawyers. Moreover, a professional athlete may earn millions annually, dwarfing the income of the U.S. president, yet the relative importance to the nation is debatable. Despite the vital role elementary school teachers play, their salaries pale in comparison to those of sports agents, advertising executives, and many others whose contributions are arguably less essential.

Third, the functionalist perspective assumes that individuals ascend the socioeconomic hierarchy based on their abilities, skills, knowledge, and overall merit. This suggests that those who do not progress lack the necessary merit. However, this viewpoint overlooks the pervasive influence of unequal opportunities in shaping social stratification. Subsequent modules in this book discuss how factors such as race, ethnicity, gender, and class position profoundly affect individuals’ opportunities to attain the necessary skills and training for occupations discussed within the functionalist framework.

While the functionalist perspective may offer some insights, it falls short in explaining the glaring disparities in wealth and poverty witnessed not only in the United States but also in other nations. Even if we argue that higher incomes are necessary to incentivize individuals to pursue professions such as medicine, it doesn’t necessarily justify the prevalence of poverty. Do CEOs truly require multimillion-dollar salaries to attract qualified candidates? Is the allure of challenge, favorable working conditions, and other perks not motivation enough for individuals to pursue high-paying positions? These questions remain unanswered by the functionalist framework, highlighting its limitations in addressing the complexities of economic inequality.

Another line of functionalist thinking directs its attention more specifically toward poverty rather than addressing social stratification in general. This functionalist perspective boldly argues that poverty endures because it serves certain beneficial roles within our society. These roles include the following: (1) individuals living in poverty undertake tasks that others are unwilling to perform; (2) the programs designed to aid impoverished individuals generate numerous employment opportunities; (3) impoverished individuals contribute to the economy by purchasing goods like day-old bread and secondhand clothing, thus enhancing the economic utility of these items; and (4) those in poverty create employment opportunities for professionals such as doctors, lawyers, and teachers who may not be qualified for positions serving wealthier clientele (Gans 1972). Due to poverty fulfilling these functions and more, the affluent classes have a vested interest in disregarding poverty to ensure its continued existence.

The conflict perspective

Conflict theory’s perspective on stratification builds upon Karl Marx’s notion of class-based societies and critiques the functionalist viewpoint previously discussed. Various interpretations rooted in conflict theory exist, all positing that social stratification arises from a fundamental conflict between the interests of the powerful, termed as the “haves,” and those of the weak, known as the “have-nots” (Kerbo 2012). These individuals at the top of the social hierarchy exploit their position to perpetuate their dominance, even if it entails suppressing those at the bottom. At the very least, they wield considerable influence over legal systems, media, and other institutions, thereby reinforcing society’s class divisions.

Conflict theory generally ascribes social stratification and consequently poverty to the absence of opportunities resulting from discrimination and bias against marginalized groups such as the poor, women, and people of color. This perspective echoes one of the initial criticisms outlined in the previous section against the functionalist perspective. As previously mentioned, several subsequent modules in this book investigate the multitude of challenges that hinder upward mobility and the pursuit of healthy and fulfilling lives for individuals from these marginalized groups in the United States.

The symbolic interactionism perspective

Symbolic interactionism, with its focus on individual interactions and interpretations in everyday life, seeks to comprehend stratification, including poverty. Unlike functionalist and conflict perspectives, it doesn’t aim to provide a root cause explanation for the existence of stratification. Instead, it examines how stratification influences people’s lifestyles and their interactions with others.

Numerous sociological texts meticulously examine the lives of both urban and rural impoverished communities from a symbolic interactionist perspective (Anderson 1999; C. M. Duncan 2000; Liebow 1993; Rank 1994). Though these works vary in their subjects and settings, they collectively highlight the harsh reality that the poor often endure lives marked by silent anguish, necessitating various coping mechanisms to navigate their circumstances. Through vivid narratives, these texts humanize the consequences of poverty, providing readers with intricate insights into the daily struggles of impoverished individuals.

Classic journalistic works by authors outside the realm of social sciences also offer vivid portrayals of the lives of impoverished individuals (Bagdikian 1964; Harrington 1962). Following this tradition, a newspaper columnist who experienced poverty firsthand recently reminisced, “I know the feel of thick calluses on the bottom of shoeless feet. I know the bite of the cold breeze that slithers through a drafty house. I know the weight of constant worry over not having enough to fill a belly or fight an illness…Poverty is brutal, consuming and unforgiving. It strikes at the soul” (Blow 2011:A19).

Taking a lighter approach, instances of the symbolic interactionist framework are evident in various literary works and films illustrating the challenges encountered when individuals from different socio-economic backgrounds interact. For instance, in the film Pretty Woman, Richard Gere portrays a wealthy businessman who engages the services of a prostitute, played by Julia Roberts, to accompany him to upscale events. Robert’s character undergoes a transformation, needing to acquire a new wardrobe and adapt to the etiquette of affluent social circles. The humor and emotional depth of the film arise from her struggles in assimilating into an affluent lifestyle.

Perspectives of poverty

The functionalist and conflict perspectives broadly address social stratification but do so indirectly regarding poverty. It wasn’t until the 1960s when poverty gained national attention that scholars began to specifically investigate why individuals become and remain impoverished. Two contrasting explanations emerged, centering on whether poverty stems from issues within the poor themselves or from societal factors (Rank 2011). The former aligns with the functional theory of stratification and can be viewed as an individualistic explanation. The latter, stemming from conflict theory, offers a structural explanation, highlighting systemic issues within American society that contribute to poverty. Table 11. “Explanations ofpPoverty” summarizes these perspectives.

Table 11. Explanations of poverty

|

Explanation |

Major Assumptions |

|---|---|

| Individualistic | Poverty results from the fact that poor people lack the motivation to work and have certain beliefs and values that contribute to their poverty. |

| Structural | Poverty results from problems in society that lead to a lack of opportunity and a lack of jobs. |

Source: University of Minnesota Libraries. 2016. Social Problems: Continuity and Change. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Libraries Publishing.

It’s crucial to determine which explanation is more plausible because, as sociologist Theresa C. Davidson (2009) notes, “beliefs about the causes of poverty shape attitudes toward the poor” (p. 136). More specifically, the explanation that individuals prefer influences their perception of government interventions aimed at assisting those in poverty. Those who attribute poverty to systemic issues within society are far more inclined than those who attribute it to personal shortcomings to advocate for increased government assistance for the impoverished (Bradley and Cole 2002). The explanation of poverty we endorse presumably impacts the level of empathy we feel towards those experiencing poverty, and our empathy, or lack thereof, subsequently influences our stance on the government’s role in poverty alleviation efforts. Keeping this context in mind, what do the individualistic and structural explanations of poverty suggest?

Individualistic explanation

The individualistic explanation suggests that personal problems and deficiencies are the primary reasons for poverty among the poor. Historically, there was a perception that the poor were biologically inferior, although this viewpoint persists to some extent, it has become less prevalent. Instead, a more common belief today is that the poor lack the ambition and motivation to work hard and succeed. Surveys indicate that a majority of Americans hold this belief (Davidson 2009). A refined version of this explanation is known as the culture of poverty theory (Banfield 1974; Lewis 1966; Murray 2012). According to this theory, the poor typically possess beliefs and values that differ from those of the nonpoor, which perpetuates their poverty. For instance, they are characterized as impulsive and focused on immediate gratification rather than planning for the future.

No matter which viewpoint one adopts, the individualistic explanation can be seen as a blaming-the-victim approach (refer to Module 1 “The Importance of a Social Analytic Mind”). Critics argue that this explanation overlooks discrimination and other societal issues in the United States while overstating the differences in values between the poor and nonpoor (Ehrenreich 2012; Holland 2011; Schmidt 2012). In relation to the latter argument, they highlight that economically disadvantaged employed individuals work longer hours per week compared to their wealthier counterparts. Additionally, surveys indicate that impoverished parents place similar importance on education for their children as affluent parents do. These shared values and beliefs prompt critics of the individualistic explanation to argue that attributing poverty solely to a culture of poverty is not reasonable.

Structural explanation

According to the second perspective, known as the structural explanation, poverty in the United States is attributed to systemic issues within American society that result in unequal opportunities and a shortage of jobs. These issues encompass various forms of discrimination based on race, ethnicity, gender, and age, as well as deficiencies in education and healthcare. Additionally, structural shifts in the American economy, such as the relocation of manufacturing industries from urban areas during the 1980s and 1990s, leading to substantial job losses, contribute to the problem. These factors collectively perpetuate a cycle of poverty, wherein the children of impoverished individuals often find themselves trapped in poverty or precarious financial situations as adults.

Rank (2011) summarizes this perspective “American poverty is largely the result of failings at the economic and political levels, rather than at the individual level…In contrast to [the individualistic] perspective, the basic problem lies in a shortage of viable opportunities for all Americans” (p. 18). According to Rank, the U.S. economy has increasingly generated low-paying, part-time, and benefit-lacking jobs over recent decades. Consequently, more Americans find themselves trapped in jobs that barely lift them out of poverty, if at all. Sociologist Fred Block and his colleagues echo this critique of the individualistic viewpoint, emphasizing “Most of our policies incorrectly assume that people can avoid or overcome poverty through hard work alone. Yet this assumption ignores the realities of our failing urban schools, increasing employment insecurities, and the lack of affordable housing, health care, and child care. It ignores the fact that the American Dream is rapidly becoming unattainable for an increasing number of Americans, whether employed or not” (Block et al. 2006:17).

Most sociologists lean towards the structural explanation. Subsequent sections in this book demonstrate that racial and ethnic discrimination, inadequate access to education and healthcare, and various other challenges hinder the ability to escape poverty. Conversely, some ethnographic studies provide support for the individualistic explanation, revealing that certain values and behaviors among the poor exacerbate their situation (Small et al. 2010). For example, individuals with lower incomes exhibit higher rates of cigarette smoking (34 percent among those earning between $6,000 and $11,999 annually, compared to only 13 percent among those with incomes exceeding $90,000 (Goszkowski 2008), contributing to more severe health issues.

APPLYING A SOCIAL ANALYTIC MINDSET

Too Poor to Work?

After watching the video “The Working Poor: The Price of the American Dream” explain why you think the majority of Americans believe poor people lack the motivation to work. Consider some of the comments people posted regarding this video. Next, discuss the research on labor-force participation and conclude if this data supports the belief that poor people lack motivation to work. Explain how research on this topic has impacted your thinking and perspective of the poor.

“Too Poor to Work?” by Katie Conklin, West Hills College Lemoore is licensed under CC BY 4.0

Taking an integrated perspective, certain researchers argue that the values and behaviors observed among impoverished communities stem from the condition of poverty itself (Small et al. 2010). These scholars acknowledge the existence of a culture of poverty, but they also posit that it exists as a means for the poor to navigate daily challenges imposed by their socioeconomic status. They suggest that if these challenges contribute to the formation of a culture of poverty, then poverty becomes a perpetuating cycle. Viewing poverty as both culturally and structurally rooted, these scholars advocate for initiatives aimed at enhancing structural opportunities for the impoverished while also addressing certain aspects of their values and behaviors, to effectively uplift those living in marginalized circumstances in the “other America.”

The Consequences of Poverty

Poverty carries profound repercussions for those ensnared by its grasp, regardless of its origins. Numerous studies, conducted and analyzed by scholars, government bodies, and nonprofit organizations, have extensively outlined the impacts of poverty (and near-poverty) on the lives of those affected (Lindsey 2009; Moore et al. 2010; Neville 2011). Many of these investigations zoom in on childhood poverty, revealing its enduring effects. Broadly speaking, children raised in poverty are more likely to remain impoverished into adulthood, face higher odds of dropping out of high school, have an increased likelihood of becoming teenage parents, and encounter difficulties in securing employment. While a mere 1 percent of children who never experience poverty end up grappling with it as young adults, a staggering 32 percent of children raised in poverty find themselves in similar circumstances in their early adult years (Ratcliffe and McKernan 2010).

A recent study utilized government data to track the progress of children born between 1968 and 1975 until they reached ages 30 to 37 (Duncan and Magnuson 2011). The study compared individuals who experienced poverty during their early childhood with those whose families had incomes at least twice the poverty line during the same period. In contrast to individuals who grew up in more affluent circumstances, adults who experienced poverty during their early childhood:

- completed, on average, two fewer years of schooling;

- earned incomes that were less than half of those achieved by adults from wealthier backgrounds;

- received an average of $826 more annually in food stamps;

- were nearly three times more likely to report being in poor health;

- were twice as likely to have a history of arrest (for males only); and

- were five times as likely to have become parents (for females only).

Family problems

Individuals living in poverty face a greater risk of encountering family issues such as divorce and domestic violence. As discussed in Module 3 “Social Inequality,” stress plays a significant role in exacerbating these family problems. Managing a household, caring for children, and meeting financial obligations are stressors that affect families regardless of their economic status. However, poverty adds an extra layer of stress to these challenges. Consequently, families living in poverty experience heightened levels of stress compared to wealthier families, intensifying the occurrence of various family problems. Additionally, when these issues arise, impoverished families have fewer resources at their disposal to address them compared to their wealthier counterparts. To learn more about how these stressors impact children, visit the Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs) website created by the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

EXAMINATION OF CHILDHOOD POVERTY

As highlighted in the text, childhood poverty can lead to lasting consequences throughout an individual’s life. Children who grow up in poverty are more likely to remain in poverty as adults and are at a heightened risk of engaging in antisocial behavior during their youth. Additionally, they face increased chances of experiencing unemployment, involvement in criminal activities, and other challenges as they transition into adolescence and young adulthood.

Recent findings suggest that one explanation for these outcomes lies in the neurological effects poverty has on children, which can hinder their cognitive abilities and subsequently impact their behavior and learning potential. As Duncan and Magnuson (2011) note, “Emerging research in neuroscience and developmental psychology suggests that poverty early in a child’s life may be particularly harmful because the astonishingly rapid development of young children’s brains leaves them sensitive (and vulnerable) to environmental conditions.”

In essence, poverty can alter the developmental trajectory of a child’s brain, primarily due to stress. Children raised in poverty often encounter multiple stressors such as community crime, familial conflicts, financial instability, and health issues among family members. These stressors, as observed by Grusky and Wimer (2011), not only affect mental well-being but can also manifest in physiological changes, essentially “getting under the skin” and altering the body’s response to its surroundings.

One significant physiological impact of poverty-induced stress is evidenced by Evans, Brooks-Gunn, and Klebanov (2011), who found that impoverished children experience elevated levels of stress hormones like cortisol and higher blood pressure, which impede neural development, affecting memory, language skills, behavior, and learning potential. Moreover, chronic stress can compromise the immune system, making children more susceptible to illnesses during childhood and increasing the likelihood of health problems like hypertension and obesity later in life.

The policy implications of this scientific research are clear for public health scholar Shonkoff (2011), who emphasizes the importance of addressing the needs of disadvantaged children from an early age. Similarly, Duncan and Magnuson (2013) advocate for policies that target deep and persistent childhood poverty, suggesting increased support for families with young children and improvements in living conditions and nutrition. The scientific evidence underscores the urgency of mitigating poverty’s detrimental effects during the crucial early years of a child’s life.

Duncan, Greg J. and Katherine Magnuson. 2013. “The Long Reach of Early Childhood Poverty.” Economic Stress, Human Capital, and Families in Asia: Research and Policy Challenges, 57-70.

Grusky, David and Christopher Wimer, eds. 2011. “Editors’ note.” Pathways: A Magazine on Poverty, Inequality, and Social Policy, p. 2.

Evans, Gary W., Jeanne Brooks-Gunn, and Pamela K. Klebanov. 2011. “Stressing Out the Poor: Chronic Physiological Stress and the Income-Achievement Gap.” Pathways: A Magazine on Poverty, Inequality, and Social Policy, pp. 16–21.

Health, illness, and medical care

Those living in poverty often face a myriad of health challenges, including higher rates of infant mortality, premature death in adulthood, and mental health issues. Access to adequate medical care is also more limited among the poor. Also, children from low-income families are more likely to experience malnutrition, leading to many health, behavioral, and cognitive issues. These difficulties can hinder their academic performance and future job prospects, perpetuating the cycle of poverty from one generation to the next. Prior to the full implementation of the U.S. health-care reform legislation in 2010, many impoverished individuals lacked proper health insurance coverage, resulting in overcrowded and understaffed health clinics being their primary source of medical attention.

It is unclear to what extent health disparities experienced by impoverished individuals are attributable to their financial struggles and inadequate access to quality healthcare, as opposed to their own lifestyle choices like smoking and poor diet. Regardless of the precise factors at play, poverty significantly contributes to poor health outcomes. Recent studies suggest that poverty leads to nearly 150,000 deaths each year, a figure comparable to the mortality rate from lung cancer (Bakalar 2011).

The extent to which poor individuals’ health suffers due to financial constraints and inadequate healthcare, as opposed to their own behaviors like smoking and poor dietary habits, is not fully understood. Nevertheless, what is clear is that poor health is a significant outcome of poverty. Recent studies indicate that poverty contributes to nearly 150,000 deaths each year, a figure roughly equivalent to the mortality rate from lung cancer (Bakalar 2011).

School resources

Children from low-income backgrounds often attend poorly maintained schools with insufficient resources, resulting in substandard education. Compared to their wealthier peers, they are significantly less likely to graduate from high school or pursue higher education. This lack of educational attainment perpetuates a cycle of poverty, trapping them and their offspring in a cycle of deprivation that persists across generations. Scholars discuss whether the underperformance of economically disadvantaged children primarily stems from inadequate schooling or their own impoverished circumstances. Nonetheless, irrespective of the root causes, the educational challenges stemming from poverty remain a significant consequence.

Housing and homelessness

As expected, individuals living in poverty face a higher likelihood of experiencing homelessness compared to those who are not impoverished. Additionally, they are more prone to residing in deteriorating housing conditions and facing barriers to homeownership. Many impoverished families allocate over half of their income towards rent and often reside in economically disadvantaged neighborhoods, which lack essential amenities such as job opportunities and quality education. The insufficient availability of adequate housing for the poor remains a significant nationwide issue, compounded by the alarming rates of homelessness. According to Lee et al. (2010), an estimated 1.6 million individuals, including over 300,000 children, experience homelessness at least intermittently throughout the year.

Crime and victimization

Individuals living in poverty (and those on the brink of it) are disproportionately involved in street crimes such as homicide, robbery, and burglary, as well as being the primary victims of such crimes. This module will explore various factors contributing to this intertwined relationship between poverty and street crime. Among these factors are the intense frustration and stress associated with poverty and the concentration of impoverished individuals in high-crime areas. In these neighborhoods, children are more likely to be influenced by older peers involved in gangs or criminal activities, increasing the likelihood of both perpetrating and falling victim to crime. Also, due to their higher likelihood of engaging in street crimes, poor and near-poor individuals constitute most of those arrested, convicted, and imprisoned for such offenses. Notably, most of the over 2 million individuals incarcerated in the nation’s prisons and jails come from impoverished backgrounds. Thus, criminal behavior and victimization are significant outcomes of poverty.

POVERTY POLICIES IN WESTERN DEMOCRACIES

When examining poverty rates across different countries, scholars often use a metric based on the percentage of households earning less than half of the nation’s median household income after taxes and government transfers. In data from the late 2000s, 17.3 percent of US households fell under this definition of poverty. The average poverty rate among other Western nations, excluding the United States, is 9.5 percent. Therefore, the US poverty rate is nearly twice as high as the average among these other democracies.

Why does the United States experience significantly higher poverty levels compared to its Western peers? Several distinctions between the United States and other nations emerge (Brady 2009; Russell 2011). First, other Western countries maintain higher minimum wages and more robust labor unions compared to the United States, resulting in incomes that help lift individuals above the poverty threshold. Second, compared to the United States, other nations allocate a significantly larger portion of their gross domestic product towards social expenditures, which encompass income support and various social services like child-care subsidies and housing allowances. Sociologist John Iceland (2006) highlights this, stating that “Such countries often invest heavily in both universal benefits, such as maternity leave, child care, and medical care, and in promoting work among [poor] families…The United States, in comparison with other advanced nations, lacks national health insurance, provides less publicly supported housing, and spends less on job training and job creation” (p. 136). Block and colleagues (Block et al. 2006) echo this sentiment, affirming that “These other countries all take a more comprehensive government approach to combating poverty, and they assume that it is caused by economic and structural factors rather than bad behavior” (p. 17).

The comparison between the United Kingdom and the United States offers a clear illustration of the differing strategies employed in addressing poverty. In 1994, approximately 30 percent of British children were living in poverty. However, by 2009, this number had decreased by more than half to 12 percent. In stark contrast, the child poverty rate in the United States in 2009 was nearly 21 percent, highlighting the inadequacy of the American approach compared to the more effective methods adopted by other wealthy democracies.

Britain employed three approaches to diminish its child poverty rate and provide support for impoverished children and their families. Initially, it encouraged more economically disadvantaged parents to enter the workforce by introducing several new measures, such as a national minimum wage set higher than its US equivalent and various tax benefits for low-income earners. Consequently, the proportion of single parents engaged in employment surged from 45 percent in 1997 to 57 percent in 2008. Secondly, Britain augmented child welfare benefits regardless of parental employment status. Thirdly, it extended paid maternity leave from four months to nine months, introduced two weeks of paid paternity leave, established universal preschool (which not only enhances children’s cognitive development but also facilitates parental workforce participation), amplified child-care assistance, and facilitated adjustments in working hours for parents with young children to align with their caregiving responsibilities (Waldfogel 2010). Despite the significant decline in the British child poverty rate attributed to these strategies, the child poverty rate in the US remained stagnant.

In summary, the United States experiences significantly higher poverty rates compared to other democratic nations, partly due to its comparatively lower expenditure on poverty alleviation efforts. Despite having substantial wealth, the U.S. has opted not to emulate the strategies of other countries, resulting in persistently high poverty levels. As Nobel laureate economist Paul Krugman (2006) succinctly puts it, “Government truly can be a force for good. Decades of propaganda have conditioned many Americans to assume that government is always incompetent…But the [British experience has] shown that a government that seriously tries to reduce poverty can achieve a lot” (p. A25).

Krugman, Paul. 2006. “Helping the poor, the British way.” New York Times, p. A25.

Waldfogel, Jane. 2010. Britain’s War on Poverty. New York, NY: Russell Sage Foundation.