3.1 Race & Ethnicity

The headline read, “Anger, Shock over Cross Burning in Calif. Community.” This incident occurred near the residence of a black woman in Arroyo Grande, California, a small affluent town located approximately 170 miles northwest of Los Angeles. The eleven-foot cross had recently been stolen from a nearby church.

The hate crime deeply disturbed the community, prompting a collective response from local ministers who issued a public statement condemning the act. They emphasized that burning crosses, defacing synagogue walls with swastikas, and writing hateful words on mosque doors are not mere pranks but are hate crimes intended to instill fear and intimidation. The group stressed the importance of every individual feeling safe in their daily lives and within the community.

Four individuals were apprehended four months later in connection with the cross burning and were charged with arson, hate crimes, terrorism, and conspiracy. The mayor of Arroyo Grande commended the arrests, noting that despite the city being shaken by the crime, it provided an opportunity for increased awareness and education on matters concerning diversity.

Incidents like the cross burning in this story recall the period of the Ku Klux Klan, which spanned from the 1880s to the 1960s. During this time, white men, often clad in white robes and hoods, instilled fear among African Americans in the South and elsewhere, resulting in the lynching of over 3,000 black individuals. While that era has passed, racial tensions persist in the United States, as demonstrated by this news report.

Following the urban riots of the 1960s, the Kerner Commission, appointed by President Lyndon Johnson, warned of a nation divided into two unequal societies—one black and one white. The commission attributed the riots to white racism and urged the government to address issues of employment, housing, and racial segregation.

Today, more than four decades later, racial disparities persist and, in many aspects, have worsened. Despite significant progress by African Americans, Latinx/e Americans, and other people of color, disparities in education, income, health, and other social indicators persist, exacerbated by the economic downturn since 2008. The wealth gap between racial groups has also deepened over the past two decades.

Why does racial and ethnic inequality persist? What are its various manifestations? And what can be done to address it? This module explores these questions. While racial and ethnic inequality have marred the United States since its inception, there remains hope for the future if the nation acknowledges the systemic roots of this inequality and takes concerted action to diminish it. Subsequent modules in this book will further explore the different aspects of racial and ethnic inequality. Immigration, a pressing issue today for Latinx/e and Asians and a subject of much political debate, is given special attention in our discussion on population concerns.

Race and ethnicity have deeply affected American society since the time of Christopher Columbus, when an estimated 1 million Native Americans inhabited what would become the United States. By 1900, their numbers had drastically declined to about 240,000 due to the violence inflicted by white settlers and U.S. troops, as well as diseases introduced by Europeans. Scholars assert that this widespread killing of Native Americans constituted genocide (Brown 2009).

African Americans also endured a history of mistreatment that traces back to the colonial era when Africans were forcibly brought to the Americas as slaves. Slavery persisted in the United States until it was abolished following the Civil War. Even African Americans outside the South faced racial prejudice. During the 1830s, white mobs attacked free African Americans in cities across the nation, driven by a pervasive racial bias that viewed blacks as inferior (Brown 1975). This violence persisted into the twentieth century, marked by numerous antiblack riots in 1919 that resulted in numerous fatalities. Concurrently, the Jim Crow era in the South saw the lynching of thousands of African Americans, segregation in all aspects of life, and other forms of discrimination (Litwack 2009).

During the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, immigrants from Ireland, Italy, Eastern Europe, Mexico, and Asia encountered hostility from native-born white mobs in the United States (Dinnerstein and Reimers 2009). As they arrived in large numbers, they faced physical assaults, job discrimination, and other forms of mistreatment. In the 1850s, Catholics in cities like Baltimore and New Orleans were beaten and sometimes killed by mobs. In the 1870s, riots erupted against Chinese immigrants in California and other states, resulting in violence and persecution. Hundreds of Mexicans in California and Texas were also targeted and subjected to lynching during this period.

The rise of Nazi racism in the 1930s and 1940s served as a stark reminder to Americans of the dangers of prejudice within their own country. Against this backdrop, Swedish social scientist Gunnar Myrdal’s monumental two-volume work, “An American Dilemma: The Negro Problem and Modern Democracy” (1944), garnered significant attention upon its publication. Myrdal meticulously documented the various forms of discrimination faced by African Americans at the time. The “dilemma” referred to in the book’s title encapsulated the conflict between America’s democratic ideals of equality and justice for all and the stark reality of prejudice, discrimination, and unequal opportunities.

The Kerner Commission, established in 1967, was formed to investigate the causes of the urban riots that had erupted across the United States and to provide recommendations for preventing future racial violence and fostering better economic and social opportunities for African Americans. The Kerner Commission’s 1968 report highlighted the nation’s failure to address this conflict since Myrdal’s book. Sociologists and other social scientists have cautioned that the situation for people of color has, in many respects, deteriorated since the release of the report (Massey 2007; Wilson 2009). This module provides further evidence of this situation.

The Meaning of Race & Ethnicity

In order to initiate our comprehension of racial and ethnic disparity, it is imperative to grasp the meanings of the terms. While these social labels may appear straightforward, their intricacies extend beyond initial perceptions.

Let’s begin with the concept of race, which pertains to a group of individuals who share certain inherited physical attributes such as skin color, facial features, and height. A central question regarding race revolves around whether it primarily constitutes a biological classification or a social construct. Traditionally, race has been viewed through a biological lens, a perspective that has prevailed for over three centuries, particularly since the colonization efforts of white Europeans in regions inhabited by people of diverse ethnic backgrounds. Consequently, individuals have been categorized into distinct racial groups based on observable physical traits.

It is evident that individuals in the United States and across the globe exhibit noticeable physical variations. The most prominent of these disparities is skin color, with some populations having dark skin tones while others have lighter shades. Additionally, variations exist in hair texture, lip size, and stature. Historically, scientists identified up to nine racial categories, including African, American Indian or Native American, Asian, Australian Aborigine, European (commonly referred to as “White”), Indian, Melanesian, Micronesian, and Polynesian (Smedley 2007), based on such physical distinctions.

While individuals exhibit variations in physical traits, anthropologists, sociologists, and many biologists cast doubt on the significance of these categories and challenge the biological notion of race (Smedley 2007). One reason for this skepticism is the observation that within any given racial group, there are often more physical dissimilarities than similarities between different racial groups. For instance, individuals categorized as “White” or of European descent encompass a spectrum of skin tones, ranging from very pale, as seen in individuals of Scandinavian heritage, to much darker, as observed in some Eastern European populations. Surprisingly, there are instances where individuals identified as “White” possess darker skin tones than individuals labeled as “Black” or African American. Furthermore, within the “White” category, there exists a diverse array of hair textures and eye colors, including straight or curly hair, and variations between blonde and dark hair with blue or brown eyes.

The complexities of racial classification are further compounded by historical interracial mixing, particularly evident during periods such as slavery. Consequently, African Americans exhibit a range of skin tones and other physical attributes. It is estimated that at least 30 percent of African Americans have European ancestry, while approximately 20 percent of individuals classified as “White” have African or Native American ancestry. The notion of distinct racial differences, if they ever existed centuries or millennia ago (a notion disputed by many scientists), has become increasingly blurred in contemporary society.

Another reason to challenge the biological concept of race is the arbitrary assignment of individuals or groups to racial categories. A century ago, for instance, immigrants from Ireland, Italy, and Eastern European Jewish backgrounds were not initially regarded as “White” upon arriving in the United States. Instead, they were often perceived as belonging to a separate, inferior (though unspecified) racial group (Painter 2011). This belief in their inferiority served to rationalize the discriminatory treatment they faced in their new homeland. Today, however, individuals from these backgrounds are commonly categorized as “White” or of European descent.

Consider the case of an individual in the United States with one White parent and one Black parent. Typically, American society identifies this person as Black or African American, a racial identity that the individual may adopt (like President Barack Obama, who had a White mother and African father). Yet, the logic behind this classification is questionable. Such an individual, including President Obama, possesses equal ancestral ties to both White and Black heritage through parental lineage. Similarly, contemplate someone with one White parent and another parent who is Biracial, with one Black parent and one White parent. Despite having three White grandparents and one Black grandparent, this person is often perceived as Black in the United States and may adopt this racial identity. This practice reflects the traditional “one-drop rule” in the United States, which defines individuals as Black if they possess any trace of Black ancestry, a rule historically employed in the antebellum South to maintain a large slave population (Staples 2005). However, in many Latin American countries, such an individual would be classified as White. These examples underscore the arbitrary nature of racial designations, highlighting race as more of a social construct than a biological one.

A third rationale for questioning the biological notion of race arises from the field of biology itself, particularly through investigations in genetics and human evolution. Regarding genetics, individuals from diverse racial backgrounds share over 99.9 percent of their DNA (Begley 2008). Conversely, less than 0.1 percent of our DNA contributes to the physical distinctions associated with racial diversity. Therefore, in terms of genetic makeup, individuals from varying racial backgrounds exhibit significantly more similarities than differences.

Furthermore, contemporary evolutionary insights emphasize the unity of humans. According to evolutionary theory, humanity originated in sub-Saharan Africa thousands of years ago. As populations dispersed worldwide over millennia, natural selection played a significant role. It favored dark skin among individuals residing in hot, sunny regions near the equator, as the presence of melanin in dark skin provides protection against sunburn, cancer, and related ailments. Conversely, in cooler, less sunny climates farther from the equator, natural selection favored lighter skin tones to facilitate the production of vitamin D, as darker skin would impede this process (Stone et al. 2007). Thus, evolutionary evidence underscores the shared humanity of individuals despite superficial variations in appearance. In essence, we are all members of one human species, notwithstanding our outward differences.

Race as a Social Construct

The arguments against the biological foundation of racial classifications indicate that race is primarily a social construct rather than a biological reality. Put differently, race is a concept shaped by society, lacking objective existence but rather defined by people’s perceptions and decisions (Berger and Luckmann 1963). In this perspective, race holds no inherent truth beyond individuals’ interpretations and societal norms. This understanding of race is evident in the challenges of categorizing individuals with multiracial backgrounds into single racial groups, as previously discussed with President Obama. Another example is golfer Tiger Woods, who, despite being predominantly of Asian descent, was often labeled as African American by the media when he rose to prominence in the late 1990s (Leland 1997).

Historical instances of racial categorization further underscore the social construction of race. In the antebellum South, for instance, the complexion of slaves often lightened over generations due to unions, often coerced, between slave owners and other White individuals. This led to court battles over individuals’ racial identities, as determining who was considered “Black” became increasingly challenging. People accused of having Black ancestry would frequently seek legal recourse to establish their White identity, aiming to evade enslavement or other adversities (Staples 1998).

Although race is socially constructed, it undeniably has real-world consequences because it is perceived as tangible by individuals. Despite the minimal genetic variance accounting for physical differences associated with race, this classification leads not only to the categorization of individuals but also to differential treatment, often resulting in inequality. However, contemporary evidence suggests little, if any, scientific justification for the racial classifications that underpin many societal inequalities.

Due to the ambiguity surrounding the concept of race, many social scientists prefer to use the term ethnicity when referring to individuals of diverse cultural backgrounds, including people of color. In this context, ethnicity denotes the shared social, cultural, and historical experiences rooted in common national or regional origins, which differentiate subgroups within a population. Similarly, an ethnic group refers to a subset of a population characterized by shared social, cultural, and historical experiences, distinct beliefs, values, and behaviors, and a sense of belonging to the subgroup. By conceptualizing ethnicity and ethnic groups in this manner, these terms sidestep the biological implications associated with race and racial groups.

However, the significance attributed to ethnicity also underscores its nature as a social construct, indicating that our ethnic identity carries significant ramifications for how we are treated. Notably, history and contemporary practices demonstrate the ease with which prejudice can arise against individuals from different ethnic backgrounds. Much of the ensuing discussion in this module focuses on the prejudice and discrimination faced by non-White and non-European ethnic groups in the United States today. Moreover, ethnic conflicts persist globally, as evidenced by the ethnic cleansing and conflicts among ethnic groups in Eastern Europe, Africa, and other regions during the 1990s and 2000s. While our ethnic heritage may instill a sense of pride in many individuals, it also serves as a catalyst for conflict, prejudice, and even hatred, as exemplified by the tragic hate crime recounted at the beginning of this module.

Racial & Ethnic Prejudice

Prejudice and discrimination, topics explored in the subsequent section, are often conflated, yet they differ fundamentally. Prejudice pertains to attitudes, whereas discrimination involves behaviors. Specifically, racial and ethnic prejudice encompasses negative attitudes, beliefs, and judgments directed towards entire groups of people, as well as individual members of those groups, based on their perceived race and ethnicity. A closely related concept is racism, characterized by the conviction that certain racial or ethnic groups are inferior to one’s own. Prejudice and racism frequently stem from racial and ethnic stereotypes, which are oversimplified and erroneous generalizations about individuals due to their race and ethnicity. While variations in culture and other aspects do exist among different racial and ethnic groups in America, many of the perceptions held about these groups lack substantiation and thus qualify as stereotypes.

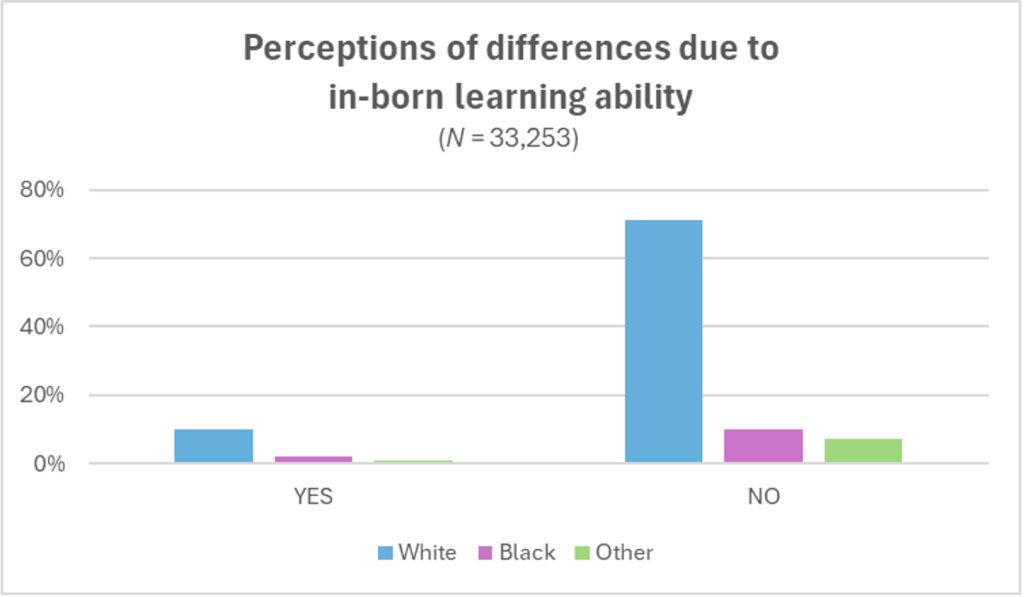

Figure 1. Perceptions of differences due to in-born learning ability

An illustrative instance of such stereotypes is depicted in Figure 1. “Perceptions of differences due to in-born learning ability” from the General Social Survey (GSS). In this recurring survey of a randomly selected sample of the U.S. population, approximately 10 % of White respondents demonstrate a tendency to African American having worse jobs, income, and housing than Whites because of their in-born ability to learn.

Understanding Prejudice

What are the origins of racial and ethnic prejudice? And why do certain individuals exhibit more prejudice than others? These inquiries have engaged scholars since at least the 1940s, a time when the atrocities of Nazism were still vivid in collective memory. Theoretical explanations for prejudice can be categorized into two main approaches: social-psychological and sociological. Initially, we will explore social-psychological perspectives before delving into sociological explanations. Additionally, we will examine how various racial and ethnic groups are misrepresented in the mass media.

Social-psychological Explanations

One of the initial social-psychological theories explaining prejudice focused on the concept of the authoritarian personality (Adorno, Frenkel-Brunswick, Levinson, and Sanford 1950). According to this perspective, authoritarian personalities develop during childhood in response to strict parenting practices. Individuals with authoritarian personalities prioritize obedience to authority, adhere rigidly to rules, and exhibit low acceptance of people from different backgrounds (out-groups). Numerous studies have identified high levels of racial and ethnic prejudice among individuals with authoritarian personalities (Sibley and Duckitt 2008). However, whether their prejudice arises directly from their authoritarian personalities or stems from the fact that their parents likely held prejudiced views themselves remains a significant question.

Another early and enduring social-psychological explanation is known as frustration theory, also referred to as scapegoat theory (Dollard, Doob, Miller, Mowrer, and Sears 1939). According to this theory, individuals experiencing various challenges become frustrated and often attribute their difficulties to groups that are commonly marginalized in society, such as racial, ethnic, and religious minorities. These minority groups serve as scapegoats for the underlying sources of people’s problems. Several psychological experiments support this theory by demonstrating that individuals tend to exhibit increased prejudice when they experience frustration.

Sociological explanations

One prevalent sociological explanation focuses on conformity and socialization, known as social learning theory. According to this theory, individuals who harbor prejudices are essentially conforming to the cultural norms prevalent in their upbringing. Prejudice is viewed as a byproduct of socialization processes influenced by parents, peers, the media, and various cultural elements. Studies supporting this perspective have shown that individuals tend to adopt more prejudiced attitudes when they reside in communities with high levels of prejudice, and conversely, they display reduced prejudice when they relocate to areas with lower levels of prejudice (Aronson 2008). For instance, if individuals in the South exhibit higher levels of prejudice compared to those in other regions, despite the abolishment of legal segregation over four decades ago, the influence of Southern culture on their socialization may help elucidate these beliefs.

FARMWORKER CHILDREN

In the vast agricultural fields of California, thousands of farmworkers and their families endure harsh living and working conditions. Both adults and children labor tirelessly under the scorching sun day after day, residing in impoverished, overcrowded dwellings.

Due to their parents’ status as migrant workers, many children attend school for only brief periods, as their families frequently relocate to different fields, towns, or even states. At Sherwood Elementary School in Salinas, California, located in the heart of the state’s agricultural region, 97 percent of students live in or near poverty. The majority, hailing from Latinx/e backgrounds, struggle with limited English proficiency, and many of their parents lack literacy skills in Spanish.

Reports indicate that numerous students at Sherwood endure living conditions where they sleep beneath carports and lack adequate space, often relying on local truck stops for basic hygiene before school. A local high school teacher lamented that many of his students rarely see their parents, who spend most of their waking hours toiling in the fields. Despite familial responsibilities and challenging circumstances, these students are expected to meet academic demands that often seem unattainable.

The plight of migrant farmworker children in California reflects broader challenges faced by Latinx/e children nationwide. The Latinx/e child population has surged in recent decades due to both reproduction and immigration, with Latinx/e kindergarteners comprising 23 percent of the total in 2009, compared to just 10 percent in 1989. This demographic shift underscores the urgent need to address the health and well-being of Latinx/e children.

However, the reality for many Latinx/e children is bleak. Approximately one-third of Latinx/e children live in poverty, often residing in disadvantaged neighborhoods where English fluency is limited, schools are inadequate, and dropout rates and teen unemployment are high. Ethnicity, poverty, language barriers, and the immigrant status of their parents collectively impede Latinx/e children’s access to essential healthcare and social services.

Amidst these challenges, the plight of farmworker children in California serves as a poignant reminder of the nation’s failure to address the needs of vulnerable populations. In a country as prosperous as the United States, the image of children from Salinas resorting to truck stops for basic hygiene before school is a glaring national disgrace. As efforts to combat racial and ethnic inequality persist, it is imperative not to overlook the plight of these marginalized children.

Brown, Patricia L. 2011. “Itinerant Life Weighs on Farmworkers’ Children.” New York Times, p. A18.

Landale, Nancy S. 2010. Growing up Hispanic: Health and Development of Children of Immigrants. Washington, DC: Urban Institute Press.

Tavernise, Sabrina. 2011. “Among Nation’s Youngest, Analysis Finds Fewer Whites.” New York Times, p. A14.

The mass media play a pivotal role in the dissemination of prejudiced attitudes. Media exposure often portrays people of color in a negative light, inadvertently reinforcing existing prejudices or even exacerbating them (Larson 2006). Examples of biased media coverage abound. Despite many poor individuals being White, news media disproportionately depict African Americans in poverty-related stories. National news magazines and television news shows, for instance, feature African Americans in nearly two-thirds of poverty-related stories, despite African Americans comprising only about one-fourth of the impoverished population. Moreover, these portrayals often misrepresent the employment status of African Americans, with only a fraction depicted as employed, contrary to reality where a significant portion of poor African Americans are employed (Gilens 1996).

Similarly, studies conducted in cities like Chicago reveal a significant overrepresentation of Whites as “good Samaritans” in television news stories, despite whites and African Americans residing in the city in roughly equal proportions (Entman and Rojecki 2001). Numerous other studies indicate that media coverage of crime and drug-related incidents disproportionately features African Americans as offenders compared to arrest statistics (Surette 2011). Collectively, these studies highlight how the media perpetuate negative stereotypes, conveying the message that black individuals are violent, lazy, and less civic-minded (Jackson 1997).

A second sociological explanation, known as group threat theory (Quillian 2006), underscores economic and political competition as key factors contributing to prejudice. In this perspective, prejudice emerges from conflicts over employment opportunities, resources, and divergent political viewpoints. When groups compete for these resources, tensions often escalate, leading to hostility between them. Within this context, individuals may develop prejudiced attitudes towards groups perceived as posing a threat to their economic or political interests. Susan Olzak’s (1994) ethnic competition theory provides a popular variation of this explanation, positing that ethnic prejudice and conflict intensify when multiple ethnic groups compete for jobs, housing, and other objectives. This competition theory aligns with the macro-level framework of the frustration/scapegoat theory previously discussed.

Much of the mob violence perpetrated by White individuals, as mentioned earlier, stemmed from concerns that the targeted groups posed a threat to their livelihoods. For example, the frequency of lynchings targeting African Americans in the South increased during periods of economic downturn and decreased during economic upswings (Tolnay and Beck 1995). Similarly, violence against Chinese immigrants by white mobs in the 1870s ensued when the pace of railroad construction, a sector that employed numerous Chinese immigrants, slowed down, prompting the Chinese to seek employment in other industries. Whites feared that this competition for jobs would adversely impact White workers and depress wages. These attacks on the Chinese community resulted in casualties and ultimately led to the passage of the Chinese Exclusion Act by Congress in 1882, which prohibited Chinese immigration (Dinnerstein and Reimers 2009).

Factors associated with prejudice

Since the 1940s, social scientists have explored the personal factors associated with racial and ethnic prejudice (Stangor 2009). These factors serve as indicators to test the presented theories of prejudice. For instance, if authoritarian personalities indeed lead to prejudice, individuals with such personalities should exhibit higher levels of prejudice. Similarly, if frustration contributes to prejudice, individuals experiencing frustration in their lives should also demonstrate higher levels of prejudice. Other factors studied as correlates include age, education, gender, region of residence, race, living in integrated neighborhoods, and religiosity. Here, we will focus on gender, education, and region of residence, particularly in the context of racial attitudes among white individuals, as most studies primarily examine white respondents due to the historical predominance of Whites in the United States.

The findings regarding gender are somewhat unexpected. Despite the common belief that women tend to be more empathetic and less racially prejudiced than men, recent research suggests that the racial attitudes of White women and men are remarkably similar, with both genders exhibiting comparable levels of prejudice (Hughes and Tuch 2003). This parallelism lends support to the earlier outlined group threat theory, suggesting that White individuals formulate their racial views more in alignment with their racial identity than with their gender identity.

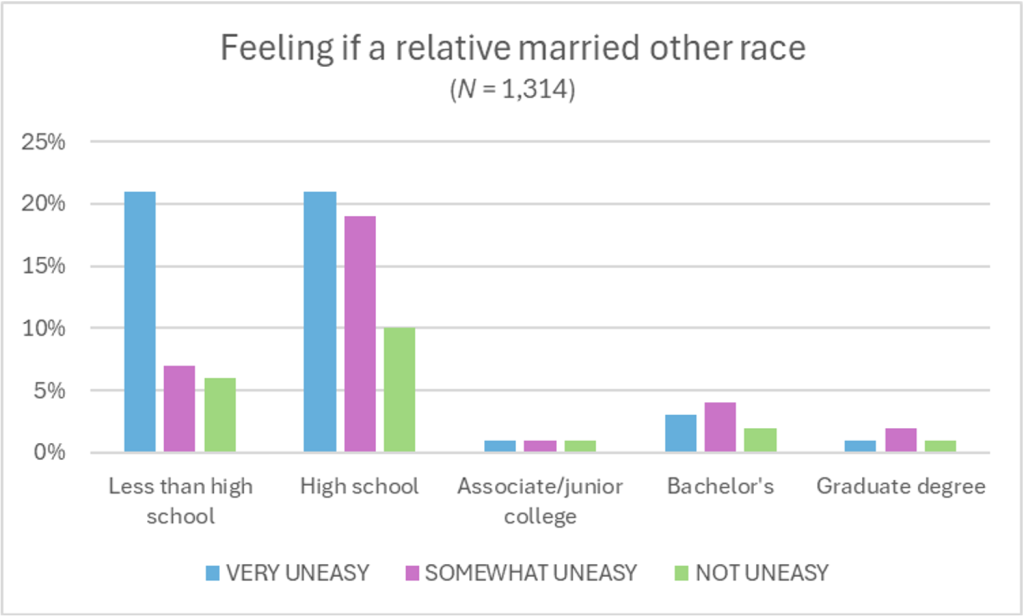

Figure 2a. Education and feeling if a relative married other race by Whites

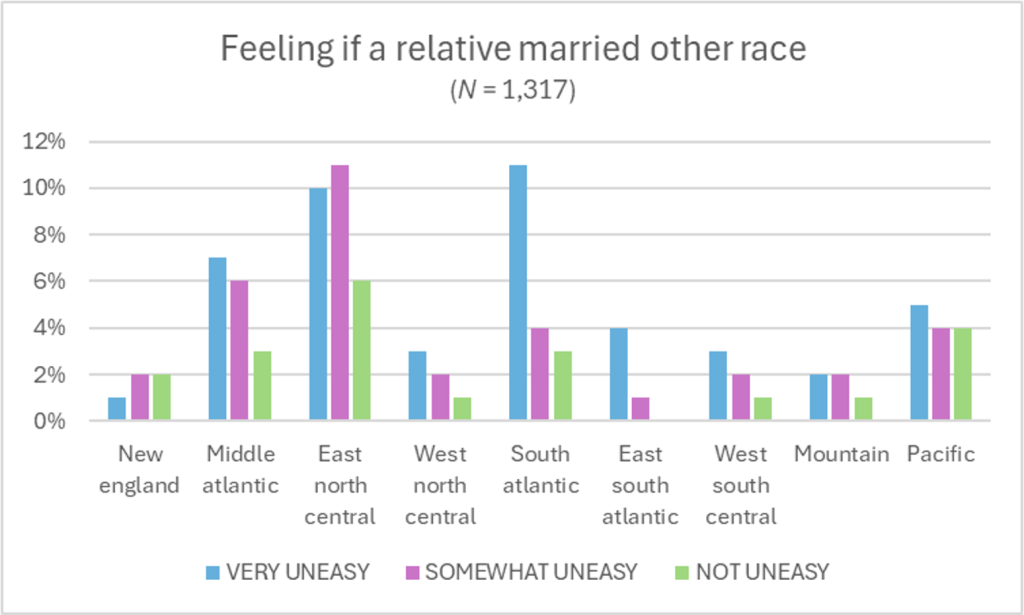

Figure 2b. Region and feeling if a relative married other race by Whites

On the other hand, the findings regarding education and region of residence align with expectations. Among White individuals, those with lower levels of education typically display higher levels of racial prejudice compared to their more educated counterparts, while Southerners tend to exhibit higher levels of prejudice than those residing in other regions (Krysan 2000). These differences are evident in Figure 2a. “Education and feeling if a relative married other race by Whites” and Figures 2b. Region, and feeling if a relative married other race by Whites,” which illustrates educational and regional disparities in a form of racial prejudice known as social distance, reflecting individuals’ sentiments toward interacting with individuals of different races and ethnicities. The General Social Survey gauges respondents’ attitudes toward a “close relative” marrying outside of their race. As depicted in Figure 2, Whites without a high school diploma are more likely to oppose such marriages compared to those with higher levels of education, and South Atlantic (Delaware, Florida, Georgia, Maryland, North Carolina, South Carolina, Virginia, and West Virginia) and East North Central (Iowa, Kansas, Minnesota, Missouri, Nebraska, North Dakota, and South Dakota) Whites are more likely to oppose them than their counterparts. These findings reaffirm the sociological perspective highlighted in Module 1, emphasizing the influence of social backgrounds on shaping attitudes.

The evolving face of prejudice

Although racial and ethnic prejudice persists in the United States, its characteristics have evolved over the past fifty years. Research examining these shifts primarily focuses on how White individuals perceive African Americans. In the 1940s and earlier, a period marked by overt Jim Crow racism, also known as traditional or old-fashioned racism, prevailed not only in the South but across the entire nation. This form of racism was characterized by explicit prejudice, staunch advocacy for segregation, and the belief in the inherent biological inferiority of Blacks compared to Whites. For instance, in the early 1940s, over half of all White individuals believed that Blacks were less intelligent than Whites, more than half supported segregation in public transportation, over two-thirds endorsed segregated schools, and more than half supported preferential treatment for Whites over Blacks in employment hiring (Schuman, Steeh, Bobo, and Krysan 1997).

The experience of the Nazi regime and subsequent civil rights movement prompted White individuals to reevaluate their perspectives, leading to a gradual decline in Jim Crow racism. Presently, few Whites subscribe to the belief that African Americans are inherently inferior biologically, and support for segregation has significantly diminished. Consequently, contemporary national surveys no longer include many of the questions posed fifty years ago regarding segregation and other Jim Crow ideologies.

However, the diminishing prevalence of overt racism does not signify the eradication of prejudice altogether. Many scholars argue that Jim Crow racism has been supplanted by a subtler form of racial bias known as laissez-faire, symbolic, or modern racism, characterized by a “kinder, gentler, antiblack ideology” devoid of biological inferiority connotations (Bobo, Kluegel, and Smith 1997, p. 15; Quillian 2006; Sears 1988). This modern prejudice entails perpetuating stereotypes about African Americans, attributing their poverty to cultural deficiencies, and opposing government assistance programs. Similar attitudes extend to Latinx/e American communities, with this new prejudice attributing their socioeconomic status to perceived laziness and lack of ambition.

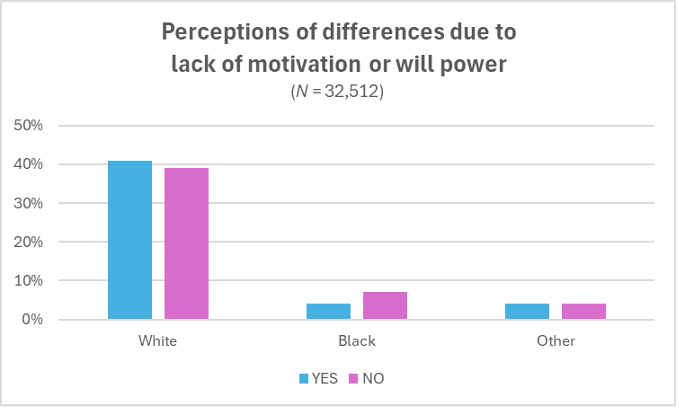

Support for this contemporary form of bias is evident in data presented in Figure 3; the question inquires whether African Americans’ socioeconomic status stems from a lack of motivation or will power to uplift themselves out of poverty. While only a small percentage of Whites attribute African Americans’ status to lower innate intelligence (see Figure 3), a significant portion attribute it to their purported lack of motivation and will power. Although this rationale may seem less overt than beliefs in biological inferiority, it still perpetuates the notion of blaming African Americans for their socioeconomic challenges.

Figure 3. Perceptions of differences due to a lack of motivation or will power

Racial & Ethnic Discrimination

Often, racial and ethnic prejudice can result in unfair treatment towards certain groups within a society. This unfair treatment, known as discrimination, involves denying rights, privileges, and opportunities to members of these groups simply because of their race or ethnicity. It’s important to note that discrimination is arbitrary, meaning it’s not based on any valid reason but solely on factors like race or ethnicity.

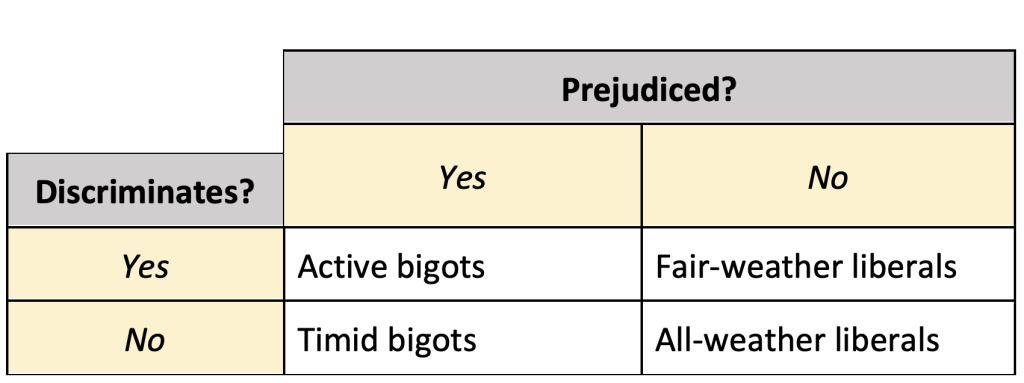

While prejudice and discrimination typically go together, Robert Merton (1949) highlighted that they don’t always occur simultaneously. Sometimes, individuals may hold prejudiced beliefs without acting on them, and conversely, individuals might discriminate without harboring prejudiced attitudes. Merton’s concept is illustrated in Table 5 “The relationship between prejudice and discrimination.” In the table, the top-left cell represents “active bigots,” who both hold prejudiced beliefs and act on them. An example would be a white apartment owner who refuses to rent to people of color due to their race. On the other hand, the bottom-right cell portrays “all-weather liberals,” individuals who neither hold prejudiced beliefs nor discriminate against others based on race or ethnicity. An example could be someone who treats everyone equally, regardless of their racial or ethnic background.

The last two cells in Table 5 “The relationship between prejudice and discrimination” offer unexpected insights. In the bottom-left cell, we encounter individuals who hold prejudiced views but don’t act on them; Merton termed them “timid bigots.” For instance, consider white restaurant owners who harbor negative feelings towards people of color but still serve them because they value their business or fear legal consequences if they refuse service.

Table 5. The relationship between prejudice and discrimination

Source: University of Minnesota Libraries. 2016. Social Problems: Continuity and Change. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Libraries Publishing.

Conversely, the top-right cell depicts “fair-weather liberals,” individuals who lack prejudiced beliefs yet engage in discriminatory behavior. An example is white store owners in the Southern United States during segregation who, despite acknowledging the injustice of treating blacks unfairly, still refused to sell to them out of fear of losing White customers.

Individual discrimination

Our discussion thus far has focused on individual discrimination, wherein individuals engage in discriminatory actions in their daily lives, often driven by prejudice but sometimes even in its absence. Joe Feagin (1991), a former president of the American Sociological Association, highlighted the prevalence of individual discrimination through his interviews with middle-class African Americans. Many reported being denied service or receiving subpar treatment in stores and restaurants. Some recounted experiences of police harassment, instilling fear merely because of their race. Feagin concluded that these incidents aren’t isolated but reflect broader racial biases ingrained in U.S. society.

The fatal shooting of Trayvon Martin in February 2012 serves as a tragic instance of individual discrimination to many observers. Trayvon, a 17-year-old African American, was walking through a gated community in Sanford, Florida, after a trip to 7-Eleven for Skittles and iced tea. George Zimmerman, an armed neighborhood watch volunteer, called 911, expressing suspicion about Martin. Despite being advised by the 911 operator not to approach: Martin Zimmerman confronted him anyway. Within minutes, Zimmerman fatally shot the unarmed Martin, later claiming self-defense. Critics of the incident argue that Martin’s sole “crime” was “walking while Black.” As an African American newspaper columnist reflected, “For every Black man in America, from the millionaire in the corner office to the mechanic in the local garage, the Trayvon Martin tragedy is personal. It could have been me or one of my sons. It could have been any of us” (Robinson 2012: A19).

In the workplace, individual discrimination is a significant issue, as highlighted by sociologist Denise Segura (1992). Segura conducted interviews with 152 Mexican American women who held white-collar positions at a public university in California. Her research revealed that over 40 percent of these women experienced discrimination at work due to their ethnicity and gender. They believed that their treatment stemmed from stereotypes perpetuated by their employers and coworkers. Additionally, they were subjected to derogatory remarks, such as “I didn’t know that there were any educated people in Mexico that have a graduate degree.”

Institutional discrimination

Addressing individual discrimination is crucial, but in today’s world, institutional discrimination holds equal if not greater significance. Institutional discrimination permeates the practices of entire institutions, including housing, medical care, law enforcement, employment, and education. Unlike individual discrimination, which may target isolated individuals, institutional discrimination impacts large numbers of individuals solely based on their race or ethnicity, and sometimes other characteristics like gender or disability.

In the realm of race and ethnicity, institutional discrimination often arises from prejudice, as seen during segregation in the South. However, institutions can also inadvertently discriminate through seemingly race-neutral practices. Individuals within institutions may unknowingly make decisions that, upon examination, disproportionately disadvantage people of color.

Institutions can discriminate even without intent. For instance, consider height requirements for police officers. Prior to the 1970s, many police forces across the United States imposed height requirements, such as five feet ten inches. As women and individuals from certain racial/ethnic backgrounds sought to join the police force, many found themselves excluded due to their height. While height requirements are considered bona fide job qualifications, the courts ruled that the height restrictions for police work lacked a logical basis. Consequently, police forces lowered their height requirements following successful legal challenges, enabling more women, Latino men, and others to join (Appier 1998).

Institutional discrimination profoundly affects the opportunities of people of color across various aspects of life today. To illustrate, we will briefly explore examples of institutional discrimination that have undergone government investigation and scholarly scrutiny.

Several research studies examine hospital records to explore whether individuals from minority racial groups receive optimal medical treatment, including procedures like coronary bypass surgery, angioplasty, and catheterization. These studies consider the medical symptoms and requirements of patients and consistently find that African Americans are significantly less likely than White individuals to undergo the procedures. This trend persists even when comparing poor African Americans to poor Whites, as well as middle-class African Americans to middle-class Whites (Smedley, Stith, and Nelson 2003).

In a unique approach to investigating racial disparities in cardiac care, a study conducted an experiment where hundreds of doctors watched videos featuring African American and White patients, all portrayed by actors. The patients in the videos presented identical complaints of chest pain and other symptoms. Doctors were then asked to determine whether they believed the patient required cardiac catheterization. The findings revealed that African American patients were less likely to be recommended for this procedure compared to white patients (Schulman et al. 1999).

Discrimination like this occurs due to various factors. While it’s conceivable that some doctors may hold explicit racist beliefs and perceive the lives of African Americans as less valuable, it’s more plausible that unconscious racial biases influence their medical judgments. Regardless of the underlying reasons, the outcome remains consistent: African Americans are less likely to undergo potentially life-saving cardiac procedures solely because of their race. Therefore, institutional discrimination in healthcare becomes a critical issue directly impacting life and death outcomes.

When loan officers assess mortgage applications, they consider various aspects such as income, employment status, and credit history. According to the law, they are prohibited from factoring in race and ethnicity during this process. However, despite these legal mandates, African Americans and Latinx/e Americans face a higher likelihood of having their mortgage applications rejected compared to Whites (Blank et al. 2005). This discrepancy persists even though individuals from these groups often have lower income levels, less favorable employment situations, and poorer credit histories than their white counterparts. While the higher rate of mortgage rejections may appear to align with these disparities, it remains a concerning issue, albeit one that reflects broader socioeconomic inequities.

To address this concern, researchers account for these factors by comparing individuals of different racial backgrounds—Whites, African Americans, and Latinx/e Americans—who have similar incomes, employment statuses, and credit histories. Some studies rely on statistical analyses, while others involve actual visits by individuals of these racial groups to the same mortgage-lending institutions. Both types of studies consistently reveal that African Americans and Latinx/e Americans are more likely than similarly qualified Whites to experience mortgage application rejections (Turner et al. 2002).

While it remains challenging to definitively ascertain whether loan officers consciously base their decisions on racial prejudice, their practices still result in racial and ethnic discrimination, regardless of their conscious intentions. This discrimination persists even when controlling for socioeconomic factors, highlighting systemic disparities within the mortgage lending process.

Evidence indicates that banks reject mortgage applications for individuals seeking homes in specific urban areas deemed high-risk, and insurance companies either deny homeowner’s insurance or impose higher premiums for properties in these neighborhoods. Such discriminatory practices against houses in certain neighborhoods are referred to as redlining, and they contravene the law (Ezeala-Harrison, Glover and Shaw-Jackson 2008). Given that those affected by redlining are often people of color, it exemplifies institutional discrimination.

Mortgage rejections and redlining contribute to a significant issue faced by people of color: residential segregation. Despite being illegal, housing segregation persists due to mortgage rejections and other factors that hinder people of color from relocating out of segregated neighborhoods and into integrated areas. African Americans, in particular, experience high levels of residential segregation in many cities, surpassing other racial groups in this regard. The extensive residential segregation of African Americans is so pronounced that it has been termed hypersegregation and more broadly labeled as American apartheid (Massey and Denton 1993).

In addition to mortgage rejections, African Americans encounter subtle discrimination from realtors and homeowners, which complicates their ability to access information about homes in predominantly White neighborhoods and purchase them (Pager 2008). For instance, realtors may inform African American clients that no homes are available in a specific White neighborhood while simultaneously alerting White clients of available properties. Although the widespread posting of housing listings on the Internet may mitigate this form of housing discrimination to some extent, not all homes and apartments are listed online, and some are sold through informal networks to prevent certain individuals from learning about them.

The hypersegregation experienced by African Americans isolates them from broader society, as many seldom venture beyond their immediate neighborhoods. This segregation results in concentrated poverty, characterized by high rates of joblessness, crime, and other social problems. For multiple reasons, residential segregation is believed to significantly contribute to the severity and persistence of African American poverty (Rothstein 2012; Stoll 2008).

Title VII of the federal Civil Rights Act of 1964 prohibited racial discrimination in employment, encompassing aspects like hiring, wages, and termination. Despite this legal framework, African Americans, Latinx/e Americans, and Native Americans still earn substantially less than their White counterparts. Various structural barriers contribute to this wage disparity, and in addition to these factors, people of color encounter ongoing discrimination in hiring and advancement opportunities (Hirsh and Cha 2008).

Determining whether such discrimination arises from conscious or unconscious bias among potential employers is challenging, yet it constitutes racial discrimination regardless of its origin. A seminal field experiment conducted by sociologist Devah Pager (2003) documented such discrimination. In the experiment, young White and African American men independently applied for entry-level jobs in person. They presented themselves similarly in terms of attire and reported comparable levels of education and qualifications. Some applicants disclosed having a criminal record, while others did not. While it was expected that applicants with a criminal record would be hired at lower rates than those without, the striking evidence of racial discrimination emerged when African American applicants without criminal records were hired at the same low rate as White applicants with criminal records.

Dimensions of Racial & Ethnic Inequality

Racial and ethnic inequality permeates every aspect of society. The discrimination, both individual and institutional, discussed earlier, exemplifies one facet of this inequality. Moreover, stark evidence of racial and ethnic disparities is evident in various government statistics. While statistics can sometimes be misleading, in the case of racial and ethnic inequality, they often paint a distressingly accurate picture.

By studying the structure of social institutions, we understand how race, ethnicity, and other social categories work as systems of power. The social world we live in is supported by ideological beliefs that make existing power structures and discrimination appear normal (Andersen and Collins 2010). However, the social categories we use to label or identify people are socially constructed and developed through historical processes and intergroup relations. Additionally, these constructs are defined in binary terms of “either/or” (e.g., Black/White, female/male, poor/rich, gay/straight, alien/citizen, etc.) which create “otherness” stigmatizing minority or subordinate groups as out-groups by the majority or powerful (Andersen and Collins 2010). Otherness directly relates to the advantages and disadvantages of individuals and groups based on their status or location in the stratified society. Because racial formation and racism shape everyday life, we find significant indicators of inequity for Americans of color in family income, poverty, home ownership, education level, and employment.

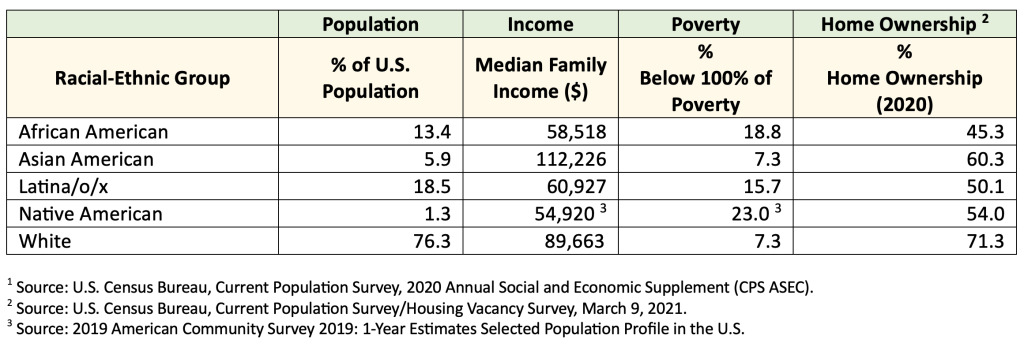

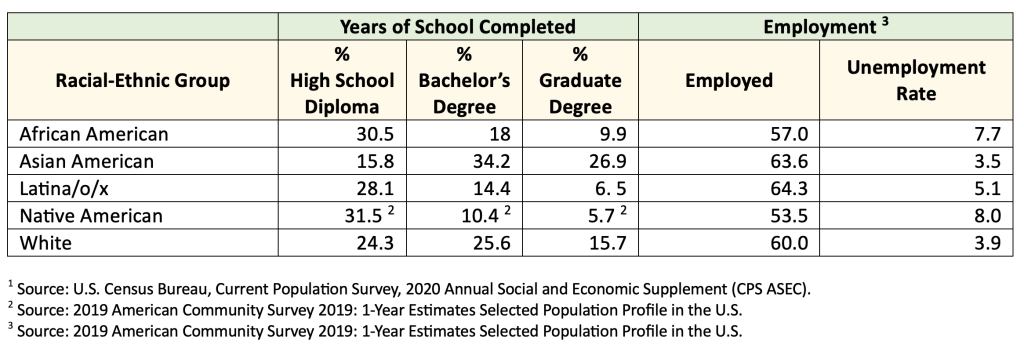

Table 6a. Indicators of racial-ethnic inequity in the United States1

Table 6b. Indicators of racial-ethnic inequity in the United States1

In the United States, under tribal sovereignty, indigenous tribes have the inherent authority to govern themselves within the nation’s borders. The U.S. recognizes tribal nations as domestic dependent nations and reaffirms adherence to the principles of government-to-government relations (The United States Department of Justice 2020). As a result, the U.S. Census Bureau has challenges in conducting and collecting accurate data in American Indian and Alaska Native areas as available data for Native Americans is presented in Tables 6a and 6b. Estimates conducted by the American Community Survey administered by the U.S. Census Bureau (https://www.census.gov/programs-surveys/acs/about/acs-and-census.html) are shown for indicators where current data is not available.

To help us understand the impact of systemic racism of Americans of color, let’s explore the data collected and published by the U.S. Census Bureau.

- According to Table 6a, which racial-ethnic groups have the lowest median family incomes?

- In the same table, which groups have the highest poverty rates?

- Which groups have the lowest homeownership rates?

- According to Table 6b, which groups complete the highest levels of education? Which groups achieve the lowest levels?

- In the same table, which groups obtain graduate (i.e., Master’s, professional, or doctorate) degrees?

- Which groups have the highest unemployment numbers? How does unemployment correspond to population size by racial-ethnic group?

- Review your analysis of the data presented in Table 6a and 6b. What racial-ethnic group patterns do you find?

Data and factual information provide relevant context to understanding racial-ethnic relations and inequality in our social world. We cannot develop the capacity to recognize, appreciate, and empathize with each other if we do not know all the facts of our country’s history and experiences of all people living in it. Current psychological research has found that knowledge of historical racism is related to own’s ability to understand contemporary racism (Feagin 2014). Data and factual information are critically important to helping us make connections that lead to insights and improvements in the quality of life for all Americans and all of humanity. Everyone has an important role to play in the future of our country and our lives together.

The data presented in Tables 6a and 6b paint a clear picture that there are significant disparities in life opportunities among racial and ethnic groups in the U.S. When compared to Whites, African Americans, Latinx/e Americans, and Native Americans experience notably lower family incomes and higher poverty rates. Additionally, they are far less likely to attain college degrees.

While Table 6a and 6b highlights the significant disparities faced by African Americans, Latinx/e Americans, and Native Americans compared to Whites, it reveals a more intricate pattern for Asian Americans. While many Asian Americans enjoy relative economic prosperity, others face greater challenges. Despite the perception of Asian Americans as a “model minority,” signifying their achievement of economic success despite not being White, disparities persist within this community. Some Asian Americans encounter barriers hindering their upward mobility, and stereotypes and discrimination against them remain prevalent issues (Chou and Feagin 2008). Moreover, the overall success rate of Asian Americans can mask the reality that their occupations and incomes often fall below expectations based on their educational attainment. Consequently, they may need to exert more effort to achieve success compared to their White counterparts (Hurh and Kim 1989).

The increasing wealth gap

At the outset of this module, we acknowledged the longstanding presence of racial and ethnic inequality in the United States, a phenomenon that scholars have cautioned may have worsened since the 1960s (Hacker 2003; Massey and Sampson 2009). Recent evidence highlighting this deterioration emerged in a report by the Pew Research Center (2011), which focused on racial disparities in wealth. Wealth encompasses a family’s total assets (such as income, savings, investments, home equity) and debts (including mortgages, credit cards, etc.).

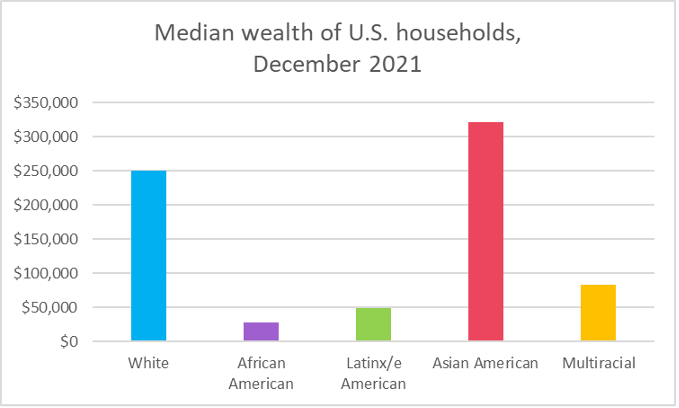

The report revealed that the wealth gap between White households and African American and Latinx/e American households had significantly widened in just a few years, largely due to the economic downturn in the U.S. since 2008, which disproportionately affected black households compared to White ones. By 2021, the median wealth of White households had surged to nine times greater than that of black households and five times greater than that of Latinx/e American households. The median wealth of Asian households risen to nearly 12 times greater than African American households and 6.5 times greater than Latinx/e American households. White households boasted a median net worth of approximately $250,400 and Asians $320,900, while Black and Latinx/e American households had median net worths of only $27,100 and $48,700, respectively (refer to Figure 4, “Median wealth of U.S. households, December 2021”).

Figure 4. Median wealth of U.S. households, December 2021

Furthermore, a significant racial/ethnic discrepancy was evident in the percentage of families with negative net worth—those whose debts surpass their assets. One-third of Black and Latinx/e American households reported negative net worth, compared to only 15 percent of White households. Consequently, Black and Latinx/e American households were more than twice as likely as White households to be in debt.

The hidden toll of inequality

A growing body of evidence suggests that navigating a society rife with racial prejudice, discrimination, and inequality exacts a “hidden toll” on the lives of African Americans (Blitstein 2009). As subsequent modules will elaborate, African Americans, on average, exhibit poorer health outcomes than Whites and have shorter lifespans. Shockingly, every year witnesses approximately 100,000 additional deaths among African Americans compared to what would be expected if they lived as long as Whites. While multiple factors likely contribute to these disparities, scholars increasingly point to the stress of being Black as a significant factor (Geronimus et al. 2010).

In this line of thought, African Americans are disproportionately more likely than Whites to contend with poverty, reside in high-crime neighborhoods, and live in cramped conditions, among numerous other challenges. As discussed earlier in this module, they also encounter racial slights, job interview refusals, and other forms of discrimination in their daily lives, regardless of their socioeconomic status. Consequently, African Americans experience elevated levels of stress from an early age, surpassing the levels experienced by most Whites. This chronic stress triggers neural and physiological effects, including hypertension (high blood pressure), which undermine African Americans’ short-term and long-term health, ultimately shortening their lifespans. These effects accrue over time: while hypertension rates are equivalent between Black and White individuals in their twenties, the Black rate escalates significantly by the time individuals reach their forties and fifties. As a recent news article succinctly summarized this phenomenon, “The long-term stress of living in a White-dominated society ‘weathers’ Blacks, making them age faster than their White counterparts” (Blitstein 2009:48).

Although research on other people of color is less extensive, many Latinx/e Americans and Native Americans also grapple with the various stressors experienced by African Americans. Consequently, racial and ethnic inequality exacts a hidden toll on members of these two groups as well. They, too, confront racial slights, endure disadvantaged living conditions, and confront other challenges that generate high levels of stress, ultimately shortening their lifespans.

White privilege

Before concluding this section, it’s important to address the advantages that White individuals enjoy in their daily lives simply because of their race. Social scientists refer to these advantages as white privilege and assert that Whites benefit from their race whether or not they are conscious of these advantages (McIntosh 2001). The discussion in this module regarding the challenges faced by people of color sheds light on some of these privileges. For instance, Whites can typically drive or walk in public spaces without fearing that law enforcement will target them solely because of their race. Reflecting on incidents like the Trayvon Martin tragedy, they can navigate streets without the fear of being confronted or harmed by a neighborhood watch volunteer. Moreover, Whites can generally move into any neighborhood they desire if they can afford it and can anticipate fair treatment in various settings such as workplaces, college dorms, restaurants, and hotels.

White individuals typically do not experience racial slurs, hate crimes, or discriminatory treatment based on their race in these spaces. Social scientist Robert W. Terry (1981) succinctly summarized white privilege as the ability to live without having to consciously consider one’s whiteness, except for those who uphold racial supremacy ideologies. For people of color in the United States, race and ethnicity are daily realities, whereas Whites often do not have to consider their racial identity in their everyday lives. This fundamental difference underscores one of the most significant manifestations of racial and ethnic inequality in the United States.

Interestingly, many studies suggest that Whites tend to underestimate the extent of racial inequality in the United States. They may assume that African Americans and Latinx/e Americans fare better than they actually do. According to one report, Whites are more than twice as likely as Blacks to believe that the position of African Americans has improved considerably (Vedantam 2008). This misperception likely diminishes Whites’ support for initiatives aimed at reducing racial and ethnic inequality.

APPLYING A SOCIAL ANALYTIC MINDSET

List of Privileges

Peggy McIntosh’s concept of the “invisible backpack” refers to the unacknowledged and unearned advantages that individuals from dominant groups, particularly white people, carry with them in society. This metaphorical backpack contains various privileges, such as the ability to find representation in media, ease in finding housing, or the benefit of the doubt in social interactions, which facilitate navigating the world more easily compared to those from marginalized groups. McIntosh’s work highlights how these privileges are often invisible to those who possess them, leading to a lack of awareness about systemic inequality and the ways in which societal structures favor certain groups over others. Here are some examples from her list:

- Representation in Media: I can turn on the television or open to the front page of the paper and see people of my race widely represented.

- Shopping Without Harassment: I can go shopping alone most of the time, pretty well assured that I will not be followed or harassed.

- Voice in Government: I can be sure that my children will be given curricular materials that testify to the existence of their race.

- Local Acceptance: I can be pretty sure that my neighbors in such a location will be neutral or pleasant to me.

- Access to Institutions: I can go into a music shop and count on finding the music of my race represented, into a supermarket and find the staple foods which fit with my cultural traditions, into a hairdresser’s shop and find someone who can cut my hair.

- Freedom from Stereotyping: I am never asked to speak for all the people of my racial group.

- Job Security: If I should need to move, I can be pretty sure of renting or purchasing housing in an area which I can afford and in which I would want to live.

- Presumption of Innocence: I can be pretty sure that if I ask to talk to the “person in charge,” I will be facing a person of my race.

- Credit and Loans: I can arrange to protect my children most of the time from people who might not like them.

- Educational Expectations: I can be reasonably sure that my children will be given curricular materials that testify to the existence of their race.

- Fair Treatment in Stores: Whether I use checks, credit cards, or cash, I can count on my skin color not to work against the appearance of financial reliability.

- Unquestioned Citizenship: I can be pretty sure that my neighbors in such a location will be neutral or pleasant to me.

- Cultural Assumptions: I can swear, or dress in second-hand clothes, or not answer letters, without having people attribute these choices to the bad morals, the poverty, or the illiteracy of my race.

- Legal Impartiality: I can do well in a challenging situation without being called a credit to my race.

- Public Safety: I can worry about racism without being seen as self-interested or self-seeking.

- Employment Confidence: If a traffic cop pulls me over or if the IRS audits my tax return, I can be sure I haven’t been singled out because of my race.

What are your unearned privileges that you carry in your invisible backpack? Consider privileges from the list provided and also think beyond the provided list including other aspects of your identity (e.g., gender, social class, education, etc.).

“List of Privileges” by Vera Kennedy, West Hills College Lemoore is licensed under CC BY 4.0

Explaining Racial & Ethnic Inequality

The reasons behind racial and ethnic inequality are complex and have sparked various viewpoints. People hold strong opinions when discussing why African Americans, Latinx Americans, Native Americans, and certain Asian Americans experience disparities compared to Whites.

One enduring explanation for racial and ethnic inequality suggests that Black and other marginalized communities are biologically inferior. This notion asserts that they possess inherent deficiencies, such as lower intelligence, which hinder their ability to obtain a quality education and pursue the American Dream. While this racist perspective was once prevalent, it is now largely discredited. Historically, Whites used this belief to justify atrocities like slavery, lynchings, and the mistreatment of Native Americans during the 1800s. In 1994, Richard J. Herrnstein and Charles Murray reignited this perspective in their controversial book, “The Bell Curve” (Herrnstein and Murray 1994). They argued that the low IQ scores of African Americans and impoverished individuals reflect genetic inferiority in intelligence, attributing African Americans’ poverty and other challenges to their purportedly low innate intelligence. Despite garnering significant media attention, few scholars endorsed their views, with many condemning their arguments as a racist attempt to “blame the victim” (Gould 1994).

Another explanation for racial and ethnic inequality centers on perceived cultural deficiencies within African American and other communities of color (Murray 1984). These supposed deficiencies include a perceived devaluation of hard work and, specifically for African Americans, a lack of strong familial bonds, which are purported to underlie the poverty and other challenges faced by these minority groups. This viewpoint mirrors the culture-of-poverty argument and remains prevalent today. As previously noted, more than half of Whites attribute Black poverty to a perceived lack of motivation and determination. Ironically, some scholars find validation for this cultural deficiency perspective in the success of many Asian Americans, often attributed to their cultural emphasis on diligence, educational attainment, and familial support (Min 2005). Proponents of this view argue that the relative lack of success among other communities of color stems from their cultures’ failure to prioritize these attributes. However, the accuracy of the cultural deficiency argument is fiercely debated (Bonilla-Silva 2009). Many social scientists find scant evidence of cultural deficiencies in minority communities and view the belief in such deficiencies as an example of symbolic racism that shifts blame onto the victim. Drawing on survey data, they assert that people of color, particularly those in poverty, value work and education for themselves and their children as much as or more than wealthier White individuals do (Holland 2011). Nonetheless, some social scientists, even those sympathetic to the structural challenges facing people of color, acknowledge the existence of certain cultural issues but stress that these stem from structural inequities. For instance, Elijah Anderson (1999) describes a “street culture” or “oppositional culture” among urban African Americans that contributes to high levels of violence. However, Anderson emphasizes that this culture emerges from the segregation, extreme poverty, and other adversities these individuals encounter daily, serving as a coping mechanism. Thus, while cultural challenges may exist, they should not overshadow the recognition that structural issues primarily drive these cultural dynamics.

RACIAL SEGREGATION OF AFRICAN AMERICANS

In a society that promotes equal opportunity, scholars have uncovered a troubling trend: African American children from middle-class backgrounds are significantly more prone than their White counterparts from similar economic backgrounds to experience downward mobility as adults. Surprisingly, almost half of African American children born to middle-class parents during the 1950s and 1960s ended up with lower incomes than their parents by adulthood, despite being raised with the values, skills, and aspirations conducive to maintaining or surpassing their socioeconomic status.

A recent study conducted by sociologist Patrick Sharkey for the Pew Charitable Trusts sheds light on a critical factor contributing to this disparity: the neighborhoods in which these children are raised. Ongoing racial segregation often compels many middle-class African American families to reside in impoverished urban areas. Sharkey’s statistical analysis revealed that neighborhood poverty significantly outweighed variables like parental education and marital status in explaining the substantial racial gap in the eventual socioeconomic outcomes of middle-class children. Additionally, the study highlighted that African American children raised in impoverished neighborhoods where the poverty rate declined ultimately achieved higher adult incomes compared to those raised in areas where poverty rates remained stagnant.

The detrimental impact of poor neighborhoods stems from various probable factors. Middle-class African American children in these areas often receive substandard education in dilapidated schools and may be influenced by peers less invested in academic pursuits, potentially leading to behavioral issues. Furthermore, the myriad challenges associated with impoverished neighborhoods likely induce considerable stress, which, as discussed elsewhere, can contribute to health problems and hinder learning abilities.

Despite some ambiguity regarding the exact causes, the study underscores the profound influence of poor neighborhoods. As summarized by a Pew official, neighborhoods emerge as significant impediments not only for the economically disadvantaged but also for those who would otherwise maintain stability. Sociologist Sharkey noted the striking racial disparities in the environments where children are raised, challenging the notion that post-civil rights era families have unrestricted access to any neighborhood. Surprisingly, the racial gap in neighborhoods has endured, as confirmed by data from the 2010 Census.

Research by sociologist John R. Logan for the Russell Sage Foundation further highlights the persistence of racial disparities in neighborhood quality. It reveals that African American and Latinx/e American families with incomes exceeding $75,000 are more likely to reside in impoverished neighborhoods compared to non-Latinx/e white families with incomes below $40,000. In essence, affluent African American and Hispanic households tend to inhabit poorer neighborhoods than lower-income white households.

The implications of this neighborhood research are clear: concerted efforts to enhance the quality and economic prospects of impoverished neighborhoods are imperative to mitigate African American poverty.

Logan, John R. 2011. Separate and Unequal: The Neighborhood Gap for Blacks, Hispanics and Asians in Metropolitan America. New York, NY: US201 Project.

MacGillis, Alec. 2009. “Neighborhoods Key to Future Income, Study Finds.” The Washington Post, p. A06.

Sharkey, Patrick. 2009. Neighborhoods and the Black-White Mobility Gap. Washington, DC: Pew Charitable Trusts.

A third explanation for racial and ethnic inequality in the United States aligns with conflict theory. This perspective attributes such inequality to structural issues, including institutional and individual discrimination, limited educational and occupational opportunities, and the dearth of adequately paying jobs (Feagin 2006). For instance, racially segregated housing confines African Americans to inner-city areas, limiting their access to neighborhoods with better employment prospects. Persistent employment bias also suppresses the wages of people of color below their potential earnings. Moreover, many children from minority backgrounds attend overcrowded and underfunded schools, perpetuating educational disparities. These challenges persist across generations, impeding upward mobility for individuals already situated at the lower rungs of the socioeconomic hierarchy due to their race and ethnicity.

As we examine the factors influencing the poverty rates among people of color, it’s insightful to analyze the economic experiences of African Americans and Latinx/e Americans since the 1990s. During that decade, the U.S. economy prospered, witnessing a decline in unemployment rates and poverty rates among African Americans and Latinx/e Americans. Conversely, since the early 2000s, particularly after 2008, the U.S. economy faced challenges, leading to an increase in unemployment and poverty rates for these groups. To interpret these trends, it’s worth considering whether African Americans and Latinx/e Americans exhibited fewer cultural deficiencies in the 1990s and more since the early 2000s or if their economic outcomes were shaped by the opportunities provided by the economy.

Economic commentator Joshua Holland (2011) offers a compelling perspective by debunking the notion of cultural deficiencies: “That’s obviously nonsense. It was exogenous economic factors and changes in public policies, not manifestations of ‘Black culture’ [or ‘Latinx/e culture’], that resulted in those widely varied outcomes… While economic swings this significant can be explained by economic changes and different public policies, it’s simply impossible to fit them into a cultural narrative.”

APPLYING A SOCIAL ANALYTIC MINDSET

Current Events: Critical Thinking Summary

Throughout the first part of the book, we examined a variety of critical thinking skills and tools used to develop a social analytic mind. Now you will be putting these skills to work as we explore current events that are impacting your community, country, and world.

Find a recent news article related to racial and ethnic inequality on the Internet. Analyze your findings using the outline below, and organize your reflections into the following:

- List the news article title, author, and publisher.

- Evaluate the credibility of the source. Not all websites are created equally. Discuss possible bias, evaluate research methods, and if conclusions are supported by evidence or data. What did you find surprising about the article? Did it change or deepen your understanding of this issue?

- Summarize the main points of the article, including what makes this information relevant to the topic of racial and ethnic inequality. Be careful in selecting your current event article – it should have enough substance to be able to complete a quality critical analysis.

- Apply two theoretical paradigms to understand how a sociologist might frame the issue. Do a critique of the article and include your personal thoughts, what you learned, and how it relates to module content.

“Current Events: Critical Thinking Summary” by Katie Conklin, West Hills College Lemoore is licensed under CC BY 4.0