1 Topic: Health as a Social Problem

Learning Outcomes:

- Analyze how social, economic, and political factors shape the perception and treatment of health issues in society.

- Evaluate the impact of social structures and inequalities on access to healthcare and overall well-being.

- Apply sociological theories to understand health as a social problem and propose potential solutions to address disparities.

By now, we probably can all tell a story about how COVID-19, an infectious disease caused by the SARS-CoV-2 virus (Coronavirus N.d.), has impacted our lives. Some of us have had family members or friends pass away. Some of us are still experiencing lingering symptoms from a COVID-19 infection, called long-haul or long COVID-19. Some of our kids felt achy or tired for a day and then got better. Some of us may not know anyone who was personally affected by COVID-19. Pause for a moment to think about your own COVID-19 health story and consider how this disease has affected society in the United States and worldwide.

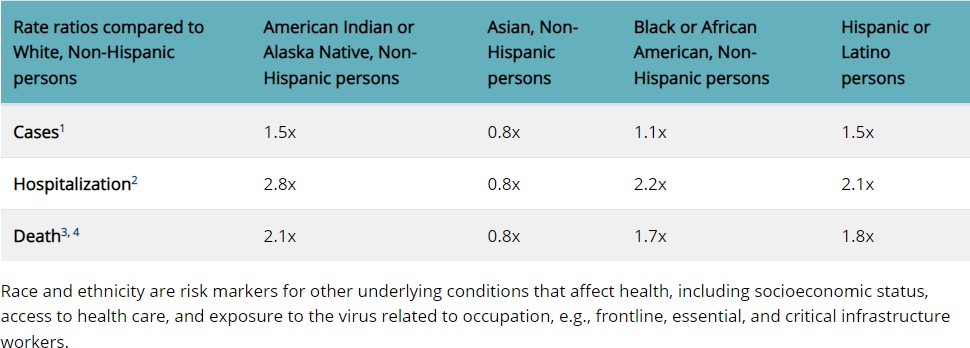

However, we have learned that some social groups are more likely to be infected, hospitalized, and even die as a result of contracting COVID-19. The table in Figure 1 shows rates of cases, hospitalizations, and deaths due to COVID-19 by race and ethnicity as of July 2020. As you can see, non-Hispanic Black people died from COVID-19 at a rate twice that of White people during this time. Please take a moment to look race the other ethnicity related to race and ethnicity in this table.

Perhaps you noticed that the data show a gap between White non-Hispanic Americans and American Indian/Alaskan Native, Asian, Black people, and Latinx people. As you can see in the table, cases, hospitalizations, and deaths for all racial and ethnic groups except for Asians are substantially higher than for Whites. This experience of inequality demonstrates that health and illness can be social problems.

This chapter will explore the social elements of health, a state of complete physical, mental, and social well-being and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity (World Health Organization 1946). We will look more deeply at why health is a social problem. We will explore collective and individual models of the social determinants of health. Asocial determinants of health of the social determinants of health, we will include the experience of individual and generational trauma as a factor in health outcomes. We will examine how sociologists make sense of health and illness by considering how these understandings develop over time. Like many other social problems, government policies and practices influence access to health resources and health outcomes. We will look at the differences in health systems internationally and decide if these systemic differences support health for everyone. Finally, we will come back to our own COVID-19 stories. The pandemic has both exposed and worsened existing inequalities. The pandemic is also inspiring creative action from individuals, communities, and governments. These generous responses demonstrate our interdependence and the need for the social justice of health.

Even with our brief explanation of COVID-19 statistics in the introduction of this chapter, we see that people experience unequal health outcomes based on their race and ethnicity. This is the health dimension of inequality in health outcomes. What else makes health and illness a social problem? Social problems characteristics of a social problem to health and illness.

Health and illness in society go beyond individual experience. We usually think of health, illness, and medicine in individual terms. When a person becomes ill, we view the illness as a medical problem with biological causes. A physician treats the individual accordingly. A sociological approach takes a different view. Unlike physicians, sociologists and other public health scholars do not try to understand why any one person becomes ill. Instead, we typically examine illness rates to explain why people from certain social backgrounds are likelier than others in society sick. Our social location in society—our social class, race and ethnicity, gender, and other dimensions of diversity—makes a critical difference.

Medical sociology is the systematic study of how societies manage issues of health and illness, such as diseases and disorders, healthcare access, and the larger picture of physical, mental, and social components of health and illness. Major topics for medical sociologists include the doctor/ patient relationship, the structure and socioeconomics of healthcare, and how culture impacts attitudes toward disease and wellness. In the next section, we’ll look at what medical sociologists find when they look at how experiences of health and illness can differ by social location.

How we get sick and how we stay healthy reveals both inequality and interdependence. For example, in Flint, Michigan, residents experienced higher-than-normal levels of lead toxicity, hair loss, rash, and other health issues when the local municipal government changed the water supply in 2013. Although government officials knew that the Flint River was contaminated with pollution from manufacturing, they decided to use this water for city residents because it was cheaper. Decisions at several interdependent layers of government resulted in this harmful action. Local citizens connected with doctors, health officials, and journalists to tell the story of the contaminated water and support a change.

More than 60% of the residents of Flint are Black. Over 40% of Flint’s residents live below the poverty line. This combination of race and class influenced the original decision-making and community response. Eventually, the Michigan Civil Rights Commission cited systemic racism as the fundamental cause for the questionable decisions. Recovery required both individual agency and collective action.

The conflict between values may cause social problems to arise. We see this as people respond to government policies around COVID-19. Promote vaccinations, asserting that scientific knowledge and research should be used to ensure our health. You may know people who support vaccines and social distancing as a way to manage the pandemic. You may know other people who think vaccines are dangerous and that state-mandated quarantining is “un-American.” This conflict in values creates the conditions in which a social problem is likely to arise.

Our ideas about what is healthy, what is illness, and what actions we should take to be healthy and treat illness are socially constructed. A sociological approach emphasizes that a society’s culture shapes its understanding of health and illness and practices of medicine. In particular, culture shapes a society’s perceptions of what it means to be healthy or ill, the reasons to which it attributes illness, and the ways in which it tries to keep its members healthy and cure those who are sick (Hahn & Inborn 2009). Knowing about a society’s culture helps us to understand how it perceives health and healing. By the same token, knowing about a society’s health and medicine helps us to understand important aspects of its culture. We’ll look more deeply into cultural constructions of health and illness in the upcoming section, Sociological Theories of Health.

As you think about your experience with COVID-19, have you changed how you think about your own health? Many people who became severely ill or died from COVID-19 had other health issues, such as hypertension and obesity. Do you know people whose attitudes about their general health have changed? Do you know people who are suspicious of the government’s intentions or less likely to listen to doctors or scientists? What do you think will be the best way to prevent illness and death should another pandemic strike? Each of these questions highlights a topic related to the social construction of the social problem of health and illness.

Epidemiology in the US: Health Disparities by Social Location

Doctors and medical professionals focus most on the health of a health dual. Sociologists and public health professionals focus on the health of health. This specialty is called epidemiology, the study of disease and health and their causes and distribution health Epidemiology can focus on the differences between neighborhoods, states, or countries. As we look at health in the Unhealth States, we see a complex and often contradictory issue. On the one hand, as one of the wealthiest nations, the United States fares well in health comparisons with the rest of the world. However, the United States lags behind almost every industrialized country in providing care to all its citizens. This gap between the shared value of health and unequal outcomes makes health and illness a social problem.

Sociologists and others who study human health have a detailed model that helps them make sense of health in groups. This model is called the social determinants of health. More specifically, the social determinants of health are the circumstances in which people are born, grow up, live, work, and age and the systems put in place to deal with illness (World Health Organization 2013). While ethnicity may seem to correlate with these elements, it is misleading to assume that all members of a specific racial group will experience the same health outcomes (Whitemarsh and Jones 2010). Instead, while certain diseases are linked to racial identity, lifestyle factors such as smoking and diet also play a role. These, of course, are also influenced by racial identity! These circumstances are shaped by a wider set of forces: economics, social policies, and politics.

Unpacking Oppression, Healing Justice: Social Determinants of Health and ACES

Sociologists and health researchers use two different models to predict health outcomes. Social determinants of health measure the social factors that may impact a community’s health outcomes. Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs) are potentially traumatic events that occur in childhood (0-17 years). The ACEs model measures the amount of trauma a child experiences and describes the impact of trauma on health outcomes. Trauma is a person’s (or group’s) response to a deeply distressing or disturbing event that overwhelms one’s ability to cope. Trauma causes feelings of helplessness, diminishes self-esteem and limits a person’s ability to feel a full range of emotions and experiences (Onderko 2018). Let’s examine both of these models.

Epidemiology in the US: Health Disparities by Social Location

We see that access to quality health care influences how healthy you might be. Whether your neighborhood is located next to an oil refinery, changes your health outcomes. You might be surprised that education access and quality also impact your health. However, you might remember that education and wealth are correlated. Wealthy people can pay more money for healthcare. Additionally, they get better educations, which sometimes leads to better health choices. The way organizations and institutions create models for the social determinants of health can change what we see. If you’d like to explore this question more deeply, here is a model from the World Health Organization and an SDOH model from the Canadian First Nations Peoples. Why might these models be different from each other? In a slightly different social model of health, researchers look at how trauma over time affects health outcomes.

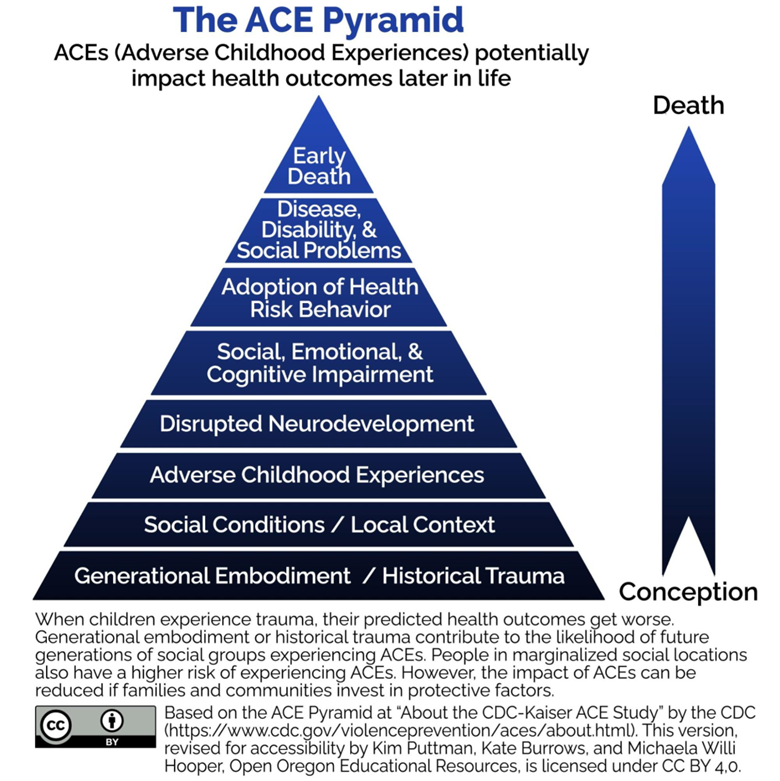

Figure 3 shows the ACE Pyramid distributed by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs) potentially impact health outcomes later in life. An arrow on the side shows the progression from conception (at the bottom) to death (at the top). The levels, from conception to death, are:

- Generational Embodiment/Historical Trauma

- Social Conditions/Local Context

- Adverse Childhood Experiences

- Disrupted Neurodevelopment

- Social, Emotional, & Cognitive Impairment

- Adoption of Health Risk Behavior

- Disease, Disability, & Social Problems

- Early Death

When children experience trauma, their predicted health outcomes get worse. These adverse or traumatic experiences may include growing up in a family with mental health or substance abuse issues, child abuse, or other experiences of violence. Because a person who experiences these events is more mental healthiness some physical and mental health challenges in childhood, they are more likely to adopt risky behaviors as an adult. Additionally, the more ACEs an adult has, the more it can predict that person’s risk of developing health problems such as diabetes, heart disease, and cancer. If left untreated, the related diseases and disabilities can lead to early death. However, when children get help from caring adults, are connected with others, or receive competent professional support, they can recover from this early trauma. These interventions and others are known as protective factors. If families and communities support children with protective factors, the negative health impacts of trauma decrease.

Many people experience at least one Adverse Childhood Experience in their lifetime. However, people in marginalized social locations have more risk of ACEs. Beyond the experience of an individual, generational embodiment or historical trauma contributes to the likelihood of future generations of social groups experiencing ACEs. Historical trauma is multigenerational trauma experienced by a specific cultural, racial or ethnic group (Administration for Children and Families N.d.). It is related to major events that oppressed a particular group of people because of their status as oppressed, such as slavery, the Holocaust, forced migration, and the violent colonization of Indigenous people in North America. The generational embodiment of this trauma means that trauma responses of a previous generation are passed down to future generations unless they are healed.

Health Inequalities by Race and Ethnicity

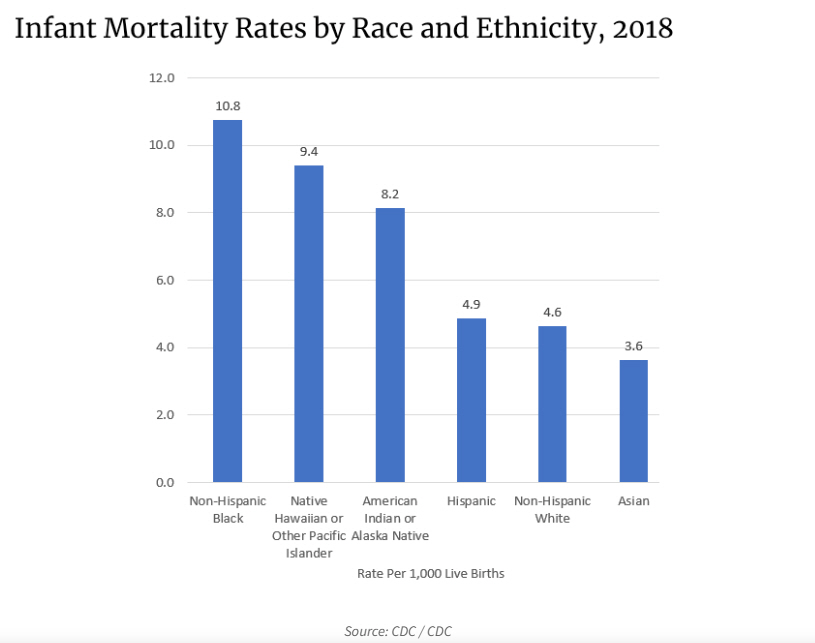

When looking at the social epidemiology of the United States, it is easy to see health disparities between people of different races and ethnicities. The discrepancy between Black and White Americans shows the gap clearly. In 2018, the average life expectancy for Black expectancy was 73 years. The average life expectancy for White males was 78.5 years. This is a gap of almost 5 years (Wamsley 2021). Mortality measures how many people die at a particular time or place. Many families have experienced the tragedy of losing an infant, and it can be hard to talk about. We see similar disparities when we look at how many babies die or infant mortality. The 2018 infant mortality rates for different races and ethnicities are as follows:

According to a report from the Kaiser Family Foundation (2007), African Americans also have a higher incidence of several diseases and causes of mortality, from cancer to heart disease to diabetes. Mexican Americans and Native Americans also have higher rates of these diseases and causes of mortality than White people.

Lisa Berkman (2009) notes that this gap started to narrow as a result of the Civil Rights movement in the 1960s but began widening again in the early 1980s. What accounts for these persistent disparities in health among different groups? Much of the answer lies in the level of healthcare that these groups have access to. The level of healthcare is measured by specific quality measures, and standards that measure the performance of healthcare providers for patients and populations. For example, quality measures include how many people get a flu shot, how long someone has to wait to see a doctor, or how often medication given for low blood pressure results in lower blood pressure. Quality measures can identify important aspects of care like safety, effectiveness, timeliness, and fairness.

The National Healthcare Disparities Report used quality measures and social location to examine healthcare inequality. Even after adjusting for insurance differences, they found that Black, Indigenous, and People of Color receive poorer quality of care and less access to care than White dominant groups. The report identified these racial inequalities in care.

- Black people, Native Americans, and Alaska Natives receive worse care than Whites for about 40 percent of quality measures, which are standards for measuring the performance of healthcare providers to care for patients and populations.

- Hispanics, Native Hawai`ians, and Pacific Islanders receive worse care than White people for more than 30 percent of quality measures.

- Asian people received worse care than White people for nearly 30 percent of quality measures but better care for nearly 30 percent of quality measures (Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality 2020).

Although there are multiple, complex reasons for discrepancies in care, a simple illustration may help make the point. Medical professionals and public health workers are asking why Black and Brown people are more likely to die of COVID-19. One medical study examined the pulse oximetry measurements of Black and White people in the hospital. If you’ve been to the hospital, you likely have had to put your finger into a little device that tells the medical professionals how much oxygen is in your blood. That’s oximetry. The study’s authors examined how often these measurements were accurate for White and Black patients.

They found that Black patients were three times more likely than White patients to have shortages of oxygen in the blood that the monitor didn’t pick up. Because COVID-19 mainly attacks the lungs and reduces oxygen, the discrepancies in the measurements of this device may lead to more medical complications in Black patients (Sjoding et al. 2021, Wallis 2021). In addition, blood oxygenation levels are part of complex automated medical alerts. If the measurements are wrong, they do not trigger the alerts which notify medical professionals to respond. Therefore, the related levels of care are lower and less effective for Black patients.

Health Inequalities by Socioeconomic Status

The social location of wealth or poverty often influences health outcomes (Patel 2020). Marilyn Winkleby and her research associates (1992) state that “one of the strongest and most consistent predictors of a person’s morbidity [incidence of disease] and mortality [death] experience is that person’s socioeconomic status (SES). This finding persists across all diseases with few exceptions, continues throughout the entire lifespan, and extends across numerous risk factors for disease.” In other words, having a lower SES makes you more likely to get sick or die of disease than people with a higher SES.

In Ijeoma Oluo’s blog post, “Healthcare…can’t live with it….can’t live without it,” the author describes her childhood experience in Japan. Feel free to read it for yourself if you’d like to. She explores how being poor changes a current healthcare crisis for her mother and her own ability to eat without pain. She writes that when you are poor, the only option you have when a tooth goes bad is to get it pulled. Even if you get richer as an adult, your mouth tells the story of your poverty because it is full of gaps (Oluo 2022). Although this post contains some strong language, feel free to read it to learn more.

Money is only part of the SES picture. Social class also influences how likely you are to have health insurance. Particularly in the United States, where healthcare is not universal, the poorer you are, the less likely you are to have quality health insurance. Suppose you have a full-time, beneficial managerial job in large multinational corporation. In that case, you will likely receive paid time off, excellent health insurance, long-term care insurance, and contributions to your retirement. This package of benefits helps you to prevent disease and stay healthy.

Conversely, suppose you have a low-wage seasonal job, particularly in a state that doesn’t participate in the Affordable Care Act. In that case, neither your employer nor the government provides health care insurance for you. You pay for your health care out of your own pocket. Given the high cost of care, you will likely delay getting treatment, not have access to preventative care, or not be able to pay for complex treatment. In the US, economics, insurance, and health outcomes are linked in enormously inequitable ways.

But economics isn’t the only driver of health outcomes. As we discussed in Chapter 6, class and education are related. Education is another variable that influences health outcomes. Phelan and Link (2003) note that many behavior-influenced diseases like lung cancer (from smoking), coronary artery disease (from poor eating and exercise habits), and HIV/AIDS initially were widespread across SES groups. However, once information linking habits to disease was shared, these diseases decreased in high SES groups and increased in low SES groups. This illustrates the important role of education initiatives regarding a given disease and possible inequalities in how those initiatives effectively reach different SES groups.

To find data on why people of low SES are more likely to contract and die from COVID-19, we look outside the United States to a study conducted in England. The study finds that people who are poor are more likely to live in overcrowded or substandard housing. These conditions make it challenging for the people who live there to quarantine effectively or maintain social distancing.

According to this study, people who are poor are more likely to be essential workers: servers, grocery clerks, delivery drivers, and other service workers. These essential workers have been required to keep their jobs and continue their interactions with many other people, increasing their risk of exposure to the virus. These essential workers are indeed heroes, but they had little choice because of their social location. If we wanted to recognize them, instead of just calling them “heroes,” we could raise wages.

Finally, because people with a lower socioeconomic status experience financial insecurity, they can be more stressed. This stress often translates into weakened immune systems, making it difficult to fight the virus. Finally, poorer people may delay going to the hospital because they have less access to quality healthcare. Because they have to wait until their health is in crisis to get medical attention, their symptoms are more severe, making it more difficult for them to recover.

Health Inequalities by Biological Sex

The Pandemic has finally opened our eyes to the fact that health is not driven just by biology, but by the social environment in which we all find ourselves and gender is a major part of that.

—Professor Sarah Hawkes, Co-Director of GH5050

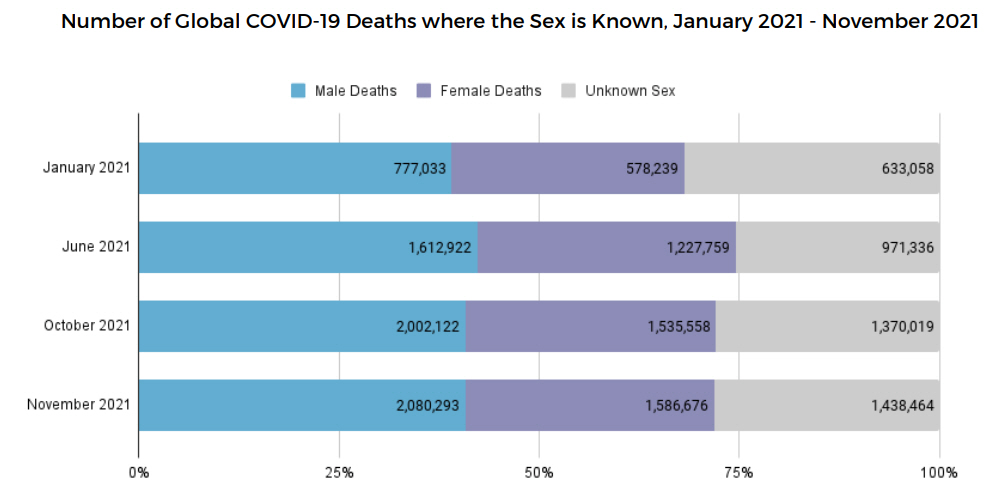

In addition to race, ethnicity, and class, gender also influences health outcomes generally, and COVID-19 outcomes more specifically. During the pandemic, women are more likely to be caregivers for family members and work as frontline health workers than men, increasing their risk of exposure.

Over time, though, worldwide data is showing that women and men are getting infected with COVID-19 at near equal rates. Stereotypes regarding the types of occupations and tasks taken on by women that led them to get more serious COVID-19 infections did not hold up once the statistics started to come in. In fact, men are more likely to die from a COVID-19 infection than women.

To understand why this is so, the social scientists from this project highlight both biological sex characteristics and socially constructed gender. They note that men have higher levels of an enzyme called ACE2. This enzyme allows viruses to enter cells more easily, which might tend to make men sicker than women. In addition to biological differences, the evidence highlights differences in behavior and social structures. In general, men tend to engage in more risky health behaviors such as drinking and smoking. These behaviors lead to poorer overall health and more risk of early death. Also, men tend to seek treatment later than women. The scientists write: However, experience and evidence thus far tell us that both sex and gender are important drivers of risk and response to infection and disease. For example, even in the case of ACE2 (the enzyme that helps the virus enter the body’s cells), there are generally more ACE2 receptors in the heart cells of someone with pre-existing heart disease. And heart disease itself is associated with gender. In many societies today it is men who are more likely to suffer from heart disease and chronic lung disease as they are more frequently smokers, drinkers, or working in occupations that expose them to the risk of air pollution.

Other gender-based drivers of inequality may include men’s generally lower use of health services, including preventive health services – which might mean that men are further along in their illness before they seek care, for example. (The Sex, Gender and COVID-19 Project 2022)

We are reacting to the COVID-19 pandemic and trying to understand complex links between the causes of pandemic sickness and death at the same time, so our scientific conclusions may change as we learn more. Even if the final analysis changes, gender is one dimension of difference that helps to explain unequal health outcomes during COVID-19.

Gender is also a key variable in understanding health with a wider lens. Women are affected adversely both by unequal access to and institutionalized sexism in the healthcare industry. According to a report from KFF, women experienced a decline in their ability to see needed specialists between 2001 and 2008. In 2008, one-quarter of women questioned the quality of their healthcare (Ranji & Salganico 2011). Quality is partially indicated by access and cost. In 2018, roughly one in four (26 percent) women—compared to one in five (19 percent) men—reported delaying healthcare or letting conditions go untreated due to cost. Because of costs, approximately one in five women postponed preventive care, skipped a recommended test or treatment, or reduced their use of medication due to cost (Ranji, Rosenzweig, and Salganicoff 2018).

In addition, many critics also point to the medicalization of women’s issues as an example of institutionalized sexism. Medicalization refers to the process by which previously normal aspects of life are redefined as deviant and needing medical attention to remedy. Historically and contemporaneously, many aspects of women’s lives have been medicalized, including premenstrual syndrome, menstruation, and menopause. The medicalization of pregnancy and childbirth has been particularly contentious in recent decades, with many women opting against the medical process and choosing natural childbirth.

Fox and Worts (1999) find that all women experience pain and anxiety during the birth process but that social support relieves both as effectively as medical support. In other words, medical interventions are no more effective than social ones at helping with the difficulties of pain and childbirth. Fox and Worts further found that women with supportive partners had less medical intervention and fewer cases of postpartum depression. Of course, access to quality reproductive health support outside the standard medical models may not be readily available to women of all social classes. It is also important to note that not all people with a uterus who may need this kind of healthcare identify as female and may face additional burdens finding reproductive healthcare.

Reproductive health is not limited to pregnancy and childbirth. It also includes the ability to choose when or whether to be pregnant. For centuries, women have controlled conception and pregnancy using plants and devices. As women’s bodies became more medicalized, contraception and termination of pregnancy became managed by doctors. In some cases, this was useful. Doctors developed “the Pill” in the 1950s. It was widely available in the 1970s (Liao and Dolin 2012). By reliably preventing conception, women had more choices in when to get pregnant. Often, this gave them more freedom to work, make money, and gain economic power.

The technology to provide safe, effective terminations of pregnancy also evolved. Abortion is the spontaneous or voluntary termination of pregnancy. As women fought to control their reproduction, the right to choose abortion became a hotly contested debate.

On January 22, 1973, the Supreme Court affirmed the right to a woman’s privacy in matters surrounding her pregnancy in a 7-2 decision, commonly known as Roe v. Wade. The decision reads in part: The Due Process Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment protects against state action the right to privacy, and a woman’s right to choose to have an abortion falls within that right to privacy. A state law that broadly prohibits abortion without respect to the stage of pregnancy or other interests violates that right. Although the state has legitimate interests in protecting the health of pregnant women and the “potentiality of human life,” the relative weight of each of these interests varies over the course of pregnancy, and the law must account for this variability (Oyez N.d.).

Since then, women have had access to abortion services in all US states. With access to safe and effective abortion, women’s health outcomes improved. Maternal mortality decreased, and there was less infant mortality (World Health Organization 2021).

However, like many social problems, some people did not agree that this law was correct. The conflict in values is based on politics, religion, and power. If you look at the conflict based on political party, you see that the Republican party argues that the unborn child has a right to life that can- not be violated. The Democratic party argues that people have the right to choose whether to get pregnant or to terminate pregnancy and to have access to safe, legal, affordable contraception and abortion.

However, not all Republicans and Democrats support their own party’s platform. Republicans who do support the platform are likely to be Protestant. 40% of them are White evangelical Christians (Lipka 2022). Republicans who don’t support the right to life are much less likely to be religious. 80% percent of Democrats support the right to life. The 20% who don’t are commonly White evangelical, Hispanic Catholic, or Black Protestant. The combination of race and religion appears to have a unique influence on beliefs about reproductive rights (Lipka 2022).

But differences in politics and religion mask a deeper divide: the debate over who controls women’s bodies. Generally, men make the laws that control women and pregnant people’s bodies.

We see the power of patriarchal systems in the challenges to Roe v. Wade. On June 24, 2022, access to abortion was removed as a federally protected right. Each state could decide whether abortions were legal or illegal. Many states limited the right to abortion. Other states protected the right to abortion.

The Supreme Court’s decision to have states decide abortion rights has worsened health outcomes for women, particularly if they are poor or women of color. Women and people with uteruses may be arrested in some states if they have abortions. Doctors may face legal charges if they take action to terminate pregnancies, even when it is to save the mother’s life. In mid-October 2022, a doctor was concerned about legal action in one case where the fetus would not survive at birth. The woman endured “a roughly six-hour ambulance ride to end her pregnancy in North Carolina, where she arrived with dangerously high blood pressure and signs of kidney failure” (Kusisto 2022). Because poor women and women of color, who are disproportionately poor, can’t afford to travel to states that protect abortion rights, they are even more at risk.

The medicalization of health, particularly regarding reproduction, encourages women and pregnant people to work for reproductive justice, a framework that centers on the human right to have children, not have children, and parent the children we have in safe and healthy environments.

Health Inequalities by Sexual Orientation and Gender Identity

Gender identity and sexual orientation may also impact how a person experiences health and illness. However, understanding these unequal experiences based on sociological data is challenging. Because it has been illegal to be queer or transgender until recently in the United States, many people do not disclose their unique identities. The agencies that sexual orientation gender identity and sexual orientation have only recently begun to re-tool their sexual orientations so that people can report their gender identity or sexual orientation. Despite these limitations, though, we notice inequality.

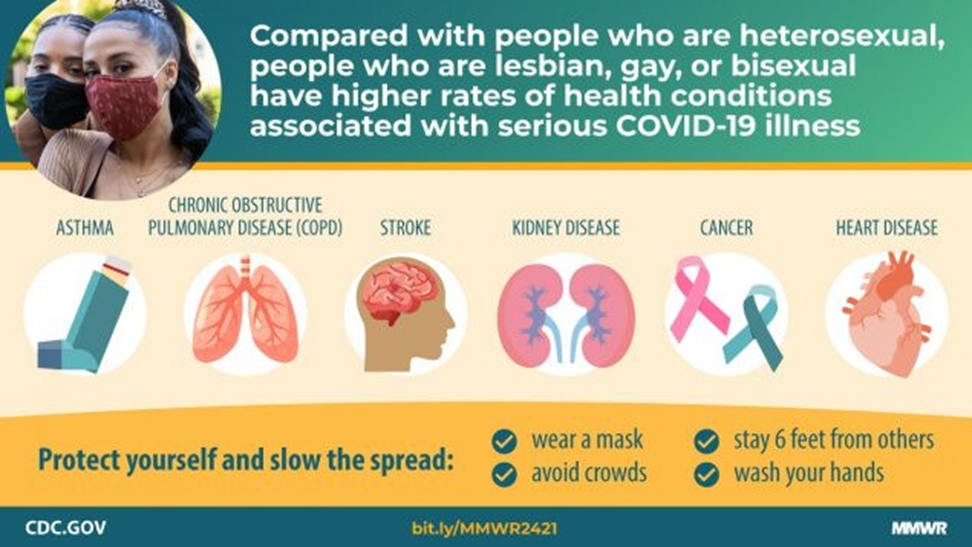

For example, when the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) examined risk factors for COVID-19 illness or death, they found that gay, lesbian, and bisexual people had challenging underlying health conditions more often than straight people. The report points primarily to economic causes as a core cause of the difference, indicating that lesbian, gay, and bisexual people, particularly if they are Black or Brown, experience less economic stability (Heslin and Hall 2021).

When examining the overall health of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender people, the American College of Physicians finds similar issues. They also highlight the connections between laws, discrimination, and rejection that result in poorer health outcomes for LGBTQIA+ people:

These laws and policies, along with others that reinforce marginalization, discrimination, social stigma, or rejection of LGBT persons by their families or communities or that simply keep LGBT persons from accessing health care, have been associated with increased rates of anxiety, suicide, and substance or alcohol abuse. (Daniel 2015)

Transgender people have unique health concerns that are rarely addressed well by current practices. Although transgender people differ in their desires regarding medical support for their physical transitions, many of the procedures are not covered by insurance. When examining health outcomes for transgender people, the report states:

Transgender persons are also at a higher lifetime risk for suicide attempt and show a higher incidence of social stressors, such as violence, discrimination, or childhood abuse, than non-transgender persons. A 2011 survey of transgender or gender nonconforming persons found that 41 [percent] reported having attempted suicide, with the highest rates among those who faced job loss, harassment, poverty, and physical or sexual assault (Daniel and Butkus 2015).

Perhaps this doesn’t need to be said, but it is not the gender identity or sexual orientation per se that causes poorer health outcomes. Instead, it is the social structure embedded with stigma, discrimination, and violence that makes life riskier and shorter for LGBTQIA+ people.

Sociological Theories of Health

Like all social problems, the concepts of health and illness are socially constructed. The definition of the social construction of illness experience is based on the idea that there is no objective reality, only our own perceptions of social constructions and the social construction of health emphasize the social and cultural aspects of the discipline’s approach to physical, objectively definable phenomena.

The Cultural Meaning of Illness

Most medical sociologists contend that illnesses have both a biological and an experiential components and that these components exist independently of each other. Dominant White culture influences the way we experience illness, dictating which illnesses are stigmatized, which are considered disabilities or impairments, and which are contestable illnesses (Conrad & Barker 2010).

Contested illnesses are those that are questioned or questionable by some medical professionals. Disorders like fibromyalgia or chronic fatigue syndrome are real physical experiences, but some medical professionals contest whether these ailments are definable in medical terms. This causes a problem for a patient with symptoms that might be explained by a contested illness—how to get the treatment and diagnosis they need in the face of a medical establishment that does not believe their symptoms are real.

We also see the social construction of health and illness when we try to measure and treat pain. Individual and cultural perceptions of pain can make it difficult for healthcare workers to treat illnesses since they cannot be measured using a device. A person’s experience of pain is subjective, and a physician’s response to treating pain is highly variable. In addition to individual and cultural differences in the response to pain, the medical system’s response to pain varies by race. Minority women are less likely to receive adequate pain medication during childbirth (Lange, Rao, and Toledo 2017) and the postpartum period (Badreldin, Grobman, and Yee 2019).

Sick Role and Functionalist Perspective

Health is vital to the stability of the society, so illness is often seen as a form of deviance. The American sociologist Talcott Parsons studied the social system. He examined the functions of sickness and health in his book The Social System, published in 1951, exploring the roles of the sick person and the doctor. The sick role is defined as patterns of expectations that define appropriate behavior for the sick and those who take care of them.

Having a physician certify that the illness is genuine is an important symbolic step in taking on the sick role. It also reveals the strong power and authority differential between the physicians. An example of the power differential between a patient and the physician is if a physician calls the patient on the phone and leaves a voice message, the social norm is that the patient will call the physician back as soon as possible.

However, if the patient calls the physician, the expectation is that it may take several days for the call to be returned. In this example, the physician’s priorities are different from that of the patient’s. The patient has more social expectations to do what the physician says, and the physician has fewer social norms compelling them to respond to the patient. A long-term illness can make our world seem smaller, more defined by the illness than anything else. An illness can be a chance for discovery, for re-imaging a new self (Conrad and Barker 2007).

Social Disparities and the Conflict Perspective

According to conflict theory, the dominant group in society, those people with power and money, make decisions about how the healthcare system runs. Therefore, they ensure that they have access to quality healthcare. To ensure that subordinate groups stay subordinate, they restrict access to care. This creates significant healthcare and health disparities between the dominant and subordinate groups. These ideas come straight from the conflict perspective introduced in Healthcare institutions including thousands of doctors, staff, patients, and administrators. They are highly bureaucratic. They do not serve every- one equally, often because of structural racism, sexism, ageism, and heterosexism. When health is a commodity, marginalized people are more likely to experience illness caused by poor diet, and living and working in unhealthy environments.

Medicalization and the Symbolic Perspective

The term medicalization of deviance refers to the process that changes bad behavior into sick behavior. A related process is demedicalization, in which sick behavior is normalized again. Both of these concepts come from the symbolic perspective of sociology, which asserts that society is created by repeated interactions between individuals and groups. Medicalization and demedicalization affect who responds to the patient, how people respond to the patient, and how people view the personal responsibility of the patient (Conrad & Schneider 1992).

So far in this chapter, we have discussed medicalization as the process in which situations and behaviors are considered medical problems rather than social problems. In the case of the medicalization of deviance, the social problems that may be medicalized are deviant behaviors. Another important example of medicalization is the significant differences in who delivers babies worldwide. In Great Britain, midwives deliver half of all babies, including Kate Middleton’s first two children, Prince George and Princess Charlotte. In Sweden, Norway, and France, midwives oversee most expectant and new mothers, enabling obstetricians to concentrate on high-risk births. In Canada and New Zealand, midwives are so highly valued that they’re brought in to manage complex cases that need special attention.

The medicalization of childbirth in the US is so pervasive that most expectant mothers in the US give birth in hospitals, with fetal monitors, medications, and other medical interventions that are unnecessary for most healthy pregnancies. In fact, severe maternal complications in the US have more than doubled in the last 20 years.

Maternity care shortages have reached critical levels, with nearly half of all US counties without a practicing obstetrician-gynecologist. In rural areas, hospitals offering obstetric services have fallen more than 16 percent since 2004. Midwives are far less prevalent in the US than in other affluent countries, attending around 10 percent of births. The extent to which they can legally participate in patient care varies widely from one state to the next. At times, the cultural stigmas regarding medical practices can cause people to seek medical services that don’t meet their needs. There are other aspects of the US healthcare system that rise as important social problems to be addressed.

Intersectional Theories of Health

When we consider the causes of poor health outcomes, a common theory about why People of Color have poor health outcomes is because they are disproportionately poor. They don’t have the money or health insurance that they need to get the needed level of medical care. This theory is partially true. However, researcher Arline Geroniumus argues that racism itself can impact health outcomes. She coined the term weathering to describe the impact that social location can have on health. Weathering is the idea that chronic exposure to social and economic disadvantage leads to an accelerated decline in physical health outcomes (Geronimus 2023).

The Hispanic Paradox

Healthcare researchers also explore health outcomes for Hispanic people. They describe these outcomes as the “Hispanic Paradox.” Hispanics make up the largest and fastest-growing minority group in the US (Funk and Lopez 2022). For decades, health services researchers have puzzled over a paradox among them. Hispanics live longer and have lower death rates from heart disease, and any other leading causes of death than non-Hispanic White people despite having social disadvantages, including lower incomes and worse access to health coverage.

There are many theories about why this might happen. The possibilities include stronger social networks, healthier eating habits, and lower smoking rates among some Hispanic groups, particularly newer arrivals. However, focusing on national data can mask important differences. It also matters if people have health insurance, speak primarily Spanish or English, or grew up in the US or another country. The very heterogeneity of the Hispanic population— they were born here and they come from more than 20 countries, with widely differing experiences and social circumstances, including immigration status makes it hard to pinpoint problems, including high rates of diabetes, liver disease, and certain cancers and poor birth outcomes among some Hispanic groups. The same diversity challenges the validity of the Hispanic paradox. (Hostetter and Klein 2018).

Health Equity is Social Justice

As we examine the social structures of health and healthcare in the US and world the governments influence health outcomes. In this policymaking step of the social problems process, governments decide who gets insurance, how people have access to healthy water, or whether health initiatives related to reproductive health. We’ll see how health laws, policies, and practices related to health care and health access affect the social problem of health.

Changing US Healthcare Policy

US healthcare coverage can broadly be divided into two main categories: public healthcare, which is funded by the government, and private healthcare, which a person buys from a private insurance company. The two main publicly funded healthcare programs are Medicare, which provides health services to people over sixty-five years old and people who meet other standards for disability, and Medicaid, which provides services to people with very low incomes who meet other eligibility requirements. Other government-funded programs include The Indian Health Service, which serves Native Americans; the Veterans Health Administration, which serves veterans; and the Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP), which serves children. Private insurance is typically categorized as either employment-based insurance or direct purchase insurance. Employment-based insurance is health plan coverage provided in whole or in part by an employer or union. It covers just the employee or the employee and their family. Direct purchase insurance is coverage that an individual buys directly from a private company.

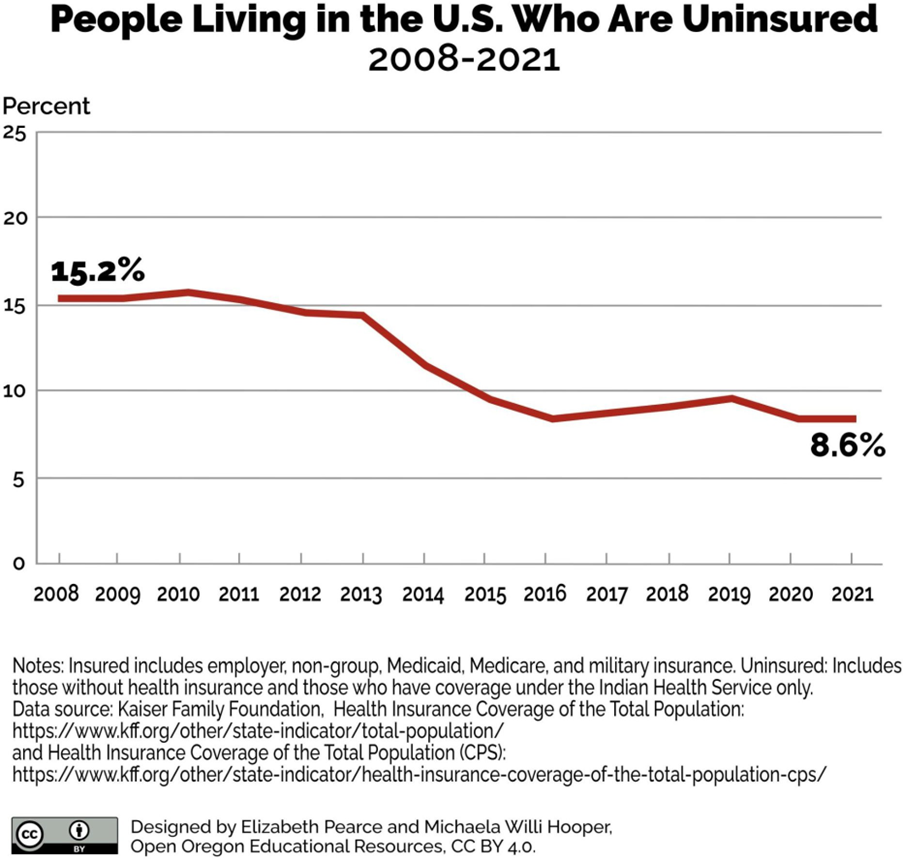

The number of uninsured people is far lower now than in previous decades, but that doesn’t mean everyone has the healthcare they need. In 2013, and in many years preceding it, the number of uninsured people was in the 40 million range, or roughly 18 percent of the population.

The Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA), which was implemented in 2014, allowed more people to get affordable insurance (Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act – Glossary N.d.) The Affordable Care Act has been a savior for some and a target for others. As Congress and various state governments sought to have it overturned with laws or to have it diminished by the courts, supporters took to the streets to express its importance to them. The Affordable Care Act (ACA) was a landmark change in US healthcare. Passed in 2010 and fully implemented in 2014, it increased eligibility to programs like Medicaid, helped guarantee insurance coverage for people with pre-existing conditions, and established regulations to ensure insurance premiums collected by insurers and care providers went directly to medical care (as opposed to administrative costs). It also included an individual mandate, which required anyone filing for a tax return to either acquire insurance coverage by 2014 or pay a penalty of several hundred dollars. Other provisions, including government subsidies, are intended to make insurance coverage more affordable, reducing the number of underinsured or uninsured people.

The ACA remained contentious for several years. The Supreme Court ruled in the case of National Federation of Independent Businesses v. Sebelius in 2012, that states cannot be forced to participate in the ACA’s Medicaid expansion. This ruling opened the door to further challenges to the ACA in Congress and the Federal courts, some state governments, conservative groups, and private businesses. The ACA has been a driving factor in elections and public opinion. In 2010 and 2014, the election of many Republicans to Congress came out of concerns about the ACA.

The uninsured number reached its lowest point in 2016, before beginning to climb again (Garfield, Orgera, and Damico 2019). People having some insurance may mask the fact that they could be underinsured; that is, people who pay at least 10 percent of their income on healthcare costs unencumbered by insurance or, for low-income adults, those medical expenses or deductibles are at least five percent of their income (Schoen et al. 2011).

However, once millions of previously uninsured people received coverage through the law, public sentiment and elections shifted dramatically. Healthcare was the top issue for voters going into the 2020 election cycle. The desire to preserve the law led to Democratic gains in the election (just a short time before COVID-19 began to spread globally). With its passage, response, subsequent changes, and new policies, the ACA demonstrates the interplay between policymaking, social problems work, and policy outcomes, the last steps of Best’s claims-making process. Even with all these options, a sizable portion of the US population remains uninsured. In 2019, about 26 million people, or eight percent of US residents, had no health insurance. That number increased to 31 million in 2020 (Keith 2020). People don’t have health insurance for many reasons. Many small businesses can’t afford to provide insurance to their employees. Many employees are part-time, so they don’t qualify for insurance benefits from their employers. Some people only have health insurance for part of a year (Keisler-Starkey and Bunch 2020). In addition, all states except for California and recently Oregon make it illegal for undocumented immigrants to receive Medicaid services through the ACA. Other states, such as Texas, are pushing to stop the spread of Medicaid to low-income citizens.

Changing Healthcare Policy Around the World

Clearly, healthcare in the United States has some areas for improvement. But how does it compare to healthcare in other countries? Many people in the United States believe that this country has the best healthcare in the world. While it is true that the United States has a higher quality of care available than many nations in the Global South, it is not necessarily the best in the world. In a report on how US healthcare compares to that of other countries, researchers found that the United States does “relatively well in some areas—such as cancer care—and less well in others—such as mortality from conditions amenable to prevention and treatment” (Docteur and Berenson 2009). This conflict between values and outcomes is another example of the conditions of a social problem: that values and outcomes do not match. Some consider the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA) to be a slippery slope that could lead to socialized medicine, a term that for many people in the United States has negative connotations lingering from socialized medicine earlier. Under a socialized medicine system, all medical facilities and expenses are covered through a public insurance plan that is administered by the federal government. It employs doctors, nurses, and other socialized medicine run the hospitals (Klein 2009). The best example of socialized medicine is in Great Britain, where the National Health System (NHS) covers the cost of healthcare for all residents. Despite some US citizens’ reactions to policy changes in socialized medicine, the United States Veterans Health Administration (VA) is administered in a similar way to socialized medicine in other countries.

It is important to distinguish between socialized medicine, in which the government owns the healthcare system, and universal healthcare, which is simply a system that guarantees healthcare coverage for everyone. Geruniversal health- care Canada all have universal healthcare. People often look to Canada’s universal healthcare system, Medicare, as a model for the system. In Canada, healthcare is publicly funded and administered by separate provincial and territorial governments.

However, the care itself comes from private providers. This is the main difference between universal healthcare and socialized medicine. The Canada Health Act of 1970 required that all health insurance plans must be “available to all eligible Canadian residents, comprehensive in coverage, accessible, portable among provinces, and publicly administered” (Kaiser Family Foundation 2010).

Reproductive Justice is Social Justice

Access to health insurance is not the only urgent social problem related to health. Issues related to reproduction and pregnancy are also social problems of health. Women have been sharing information about health forever, but this work became more focused on the 1970s women’s movement. A women’s collective wrote Our Bodies Ourselves to share concrete practical information about women’s health. In their work, they told each other stories about their first periods and how they learned about menstruation. Generally, information about periods had been shrouded in mystery and shame. The book challenges this mystery and shame related to women’s health, offering women clear, accessible information about health, information that wasn’t generally accessible at the time. This collective is still going strong today (Our Bodies Ourselves Today 2023).

Women’s commitment to reproductive justice didn’t stop with writing books and education. Feminists, including women, men, and nonreproductive justice work for reproductive justice. These efforts include supporting the 1973 Roe v Wade decision, which protected the right to have an abortion. More recently, this social movement generated several Women’s Marches in Washington D.C., and protests related to reproductive rights. The song “I Can’t Keep Quiet” became one of the anthems of recent women’s marches. Feel free to listen if you’d like.

Beyond education, writing, and protesting, many organizations provide reproductive justice through healthcare services. Sister Song, the women of color reproductive justice coalition was formed in 1997 by 16 organizations of women of color. They write: Sister Song’s mission is to strengthen and amplify the collective voices of Indigenous women and women of color to achieve reproductive justice by eradicating reproductive oppression and securing human rights (2023). They connect issues of gender, class, and race to create a national multi-ethnic movement to support reproductive justice, which includes not only access to safe abortion, but access to contraception, and freedom from forced sterilization. The organization collects funds and distributes them to birthing People of Color and queer or trans people who need birth support (Sister Song 2023).

Finally, midwives and birth doulas are offering options to ensure reproductive justice. Black Doulas, for example, help Black women and birthing people to have babies safely. This alternative is important to combat the racism in reproductive care, in which Black women are three times more likely to die than White women from pregnancy-related causes. A birth doula provides emotional and physical support to a pregnant person before, during, and after the birth. This culturally specific care improves outcomes for pregnant people: As doula care is a proven, cost-effective means of reducing racial disparities in maternal health and improving overall health outcomes, policy advocates, legislators, and other stakeholders should undertake efforts to increase Medicaid and private insurance coverage of doula services. (Robles-Fradet and Greenwald 2022). Reproductive Justice solutions include education, activism, and providing needed care. Reproductive Justice is social justice.

Chapter adapted from: “Health Equity is Social Justice” by LibreTexts is licensed under CC BY.