3 Topic: The Social Problem of Mental Health

Learning Outcomes

- Understand the social and structural factors influencing mental health and access to mental health care.

- Analyze the stigma surrounding mental illness and its impact on individuals and society.

- Evaluate policies and interventions aimed at addressing mental health as a social issue.

We examine the social problems of mental health, mental illness, and mental well-being. Our human lives contain sadness, loss, excitement, joy, and, especially in the United States, feeling like you are not enough. But what are the boundaries between having a tough week and mental illness? To begin, we’ll read my story about my interactions in a mental hospital.

At first blush, mental health appears to be a uniquely personal phenomenon: mental health, mental well-being, and mental illness seem to be intensely private experiences outside the realm of sociological analysis. After all, who but psychologists and psychiatrists are truly equipped to understand mental health and illness? In this chapter, we aim not only to understand the role of sociology in the study of mental health but to gain a deeper understanding of the effects of social life on our mental well-being. You will be introduced to the major concepts and techniques of understanding mental health and illness from a sociological perspective.

This topic is interdisciplinary. It includes material from many fields. But there is a coherent organizing theme: the need to understand mental illness in a broad social context. Too often, scientists and psychologists study people who have diseases of the mind without regard to their social origins and the institutions of social control involved in mental illness. We examine how history, institutions, and culture shape our conceptions of mental illness and people with mental health challenges. Mental health and mental illness become a social problem because of the conflict in how people disagree about these ideas. We will consider the social factors contributing to the rates and the experiences of mental illness. By this point in our exploration, you will not find it surprising that social location impacts the social problem of “Who is OK?”

We examine the epidemiology of mental health and mental illness to discover how race, class, gender, and other social locations impact how people are diagnosed and treated. We explore how sociologists explain this difference, using concepts such as stigma. Finally, we consider the interdependent nature of mental health and mental illness. These conditions impact individuals, but they also affect families and society. The questions that focus our curiosity are:

- What is the difference between mental health, mental illness, and mental well-being?

- How can we understand mental health as a social problem?

- Why do people experience different mental health issues, diagnoses, and treatments based on gender, race, class, and other social locations?

- How does the social construction of the mixed-race identity explain social inequality, particularly in relation to mental health?

- How are mental health and mental illness underlying factors in other social problems?

- How does the structural oppression of patriarchy impact social problems, particularly related to women, queer, transgender, and non-binary people?

- How do sociological explanations of mental health and mental illness differ from primarily medical or psychological models?

- What creative solutions to providing mental health services combine individual agency and collective action to expand social justice?

In our everyday lives, we might say someone is crazy. Or we might say that we feel out of it. These terms are commonly used, but social scientists must be more precise in their language. Once we have defined our terms, we explore why mental health and mental illness are social problems, not just individual ones.

Mental health is a state of mind characterized by emotional well-being, good behavioral adjustment, relative freedom from anxiety and disabling symptoms, and a capacity to establish constructive relationships and cope with the ordinary demands and stresses of life (American Psychological Association 2023). It includes our emotional, psychological, and social well-being. It affects how we think, feel, and act. It also helps determine how we handle stress, relate to others, and make choices.

Mental health includes subjective well-being, autonomy, and competence. It is the ability to fulfill your intellectual and emotional potential. Mental health is how you enjoy life and create a balance between activities. Cultural differences, your evaluation of yourself, and competing professional theories all affect how one defines mental health. Mental health is important in every stage of life, from childhood and adolescence through adulthood. When sociologists study mental health, they look at trends across groups. They look at how mental health varies between all genders, different racial and ethnic groups, different age groups, and people with different life experiences, including socioeconomic status. In addition to this, though, they also explore the factors that maintain or distract from mental health, such as stress, resilience, and coping factors, the social roles we hold, and the strength of our social networks as a source of support.

The term mental health doesn’t necessarily imply good or bad mental health. At some times in your life, you will feel really good and have good coping skills, strong social networks, a fulfilling career, and a healthy personal and family life. At other times, things may not be going so well for you. You may have work or family conflicts, you find your- self engaging in poor coping skills, not contacting your social network for support. Both times, you are dealing with mental health. In the next section, we will explore the concept of mental illness, which, contrary to common belief, is not the opposite of mental health. Rather, it is one type of experience a person can have with their mental health.

Throughout your life, if you experience mental health problems, you’re thinking, mood, and behavior could be affected. Some early signs related to mental health problems are sleep difficulties, lack of energy, and thinking of harming yourself or others. Many factors contribute to mental health problems, including:

- biological factors, such as genes or brain chemistry

- life experiences, such as trauma or abuse

- family history of mental health problems

All of us will experience mental health challenges throughout our lives—times when we’re not sleeping, eating, or socializing as well as we know we could be. We may have times when we feel mildly depressed for a matter of days or just don’t feel like doing much. These experiences are common and do not mean you have a mental illness. Mental illness, also called mental health disorders, refers to a wide range of mental health conditions and disorders that affect your mood, thinking, and behavior. Examples of mental illness include depression and other mood disorders like bipolar disorder, anxiety disorders, schizophrenia, eating disorders, and addictive behaviors (Mayo Clinic Staff 2022). When substance use disorders co-occur with other mental health disorders, it is known as dual diagnosis. Having a dual diagnosis increases symptoms and decreases responsiveness to treatment. Drug use can precipitate overdoses on drugs such as methamphetamines, cocaine, and cannabis and can also worsen diagnoses such as bipolar disorder and schizophrenia.

Unlike mental health, mental illness has a very specific definition. Psychiatrists, psychologists, and even your primary care doctor use a manual called the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM), which lists every recognized mental illness. The DSM lays out each condition—297 in the most recent iteration— that professionals recognize as a mental illness (American Psychiatric Association 2013). Each mental illness listed in the DSM has a list of diagnostic criteria that a person must meet to be considered to have that particular mental illness. For example, to get an official diagnosis of major depressive disorder, a person must meet five out of eight symptoms, such as severe fatigue, feeling hopeless or worthless, or much less interest in activities they used to enjoy, for at least two weeks to be considered clinically depressed.

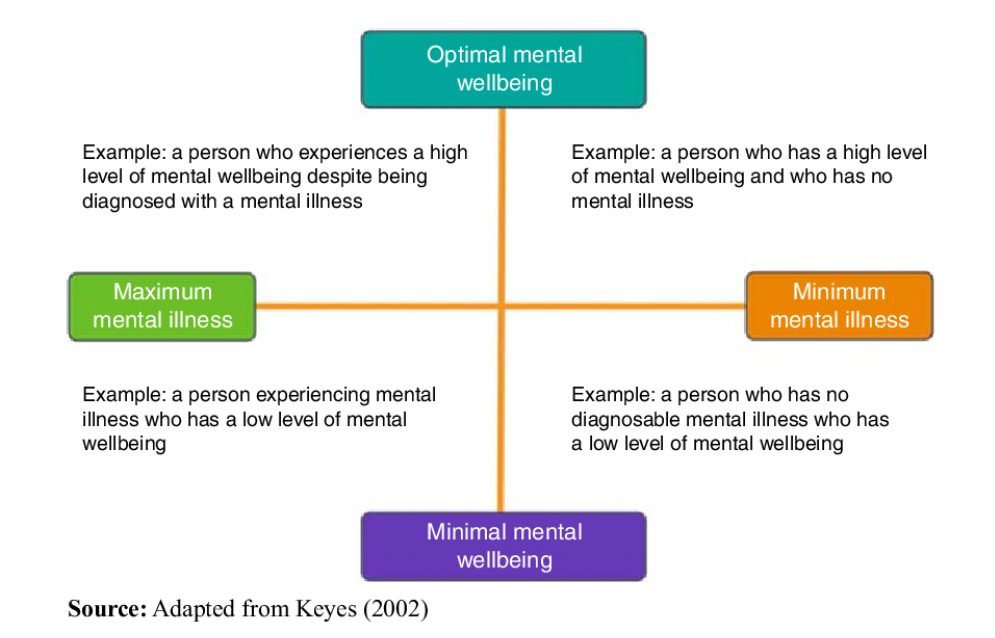

In addition to the definitions of mental health and mental illness that we commonly use to discuss diagnosis or lack thereof, some people are starting to use the description of mental well-being. Mental wellness is an internal resource that helps us think, feel, connect, and function; it is an active process that helps us to build resilience, grow, and flourish (McGroarty 2021). While people can support their mental well-being with self-care activities and connecting with family and friends, the core concept is more profound. It comprises the activities and attitudes that all of us can cultivate to ensure our resilience, whether we have a mental health diagnosis or not. The community activists and researchers who created the phrase mental well-being use it for two reasons. First, by separating a mental health diagnosis from the quality of mental well-being, we have a model that helps us understand that mental illness can be like a chronic disease. Some days, weeks, or even years, the illness is very well managed, and the person leads a productive, happy, and fulfilling life. On other days, the illness is not well managed, and the person needs more support. On the other axis, some people may experience a life event that makes them deeply sad or feel powerless. They don’t have a mental health diagnosis but may need mental health treatment or support anyway.

Second, some people and communities stigmatize people who have mental illnesses or need mental health treatment. In those cases, using the language of mental well-being avoids stigma. The National Alliance on Mental Illness (NAMI) hosts these sites, which you can explore if it interests you: Sharing Hope: Mental Wellness in the Black Community and Compartiendo Esperanza: Mental Wellness in the Latinx Community. Both sites have excellent videos exploring issues relating to mental wellness and resilience, mental health, and mental illness in these specific communities.

Mental Health and Mental Illness Go Beyond Individual Experience

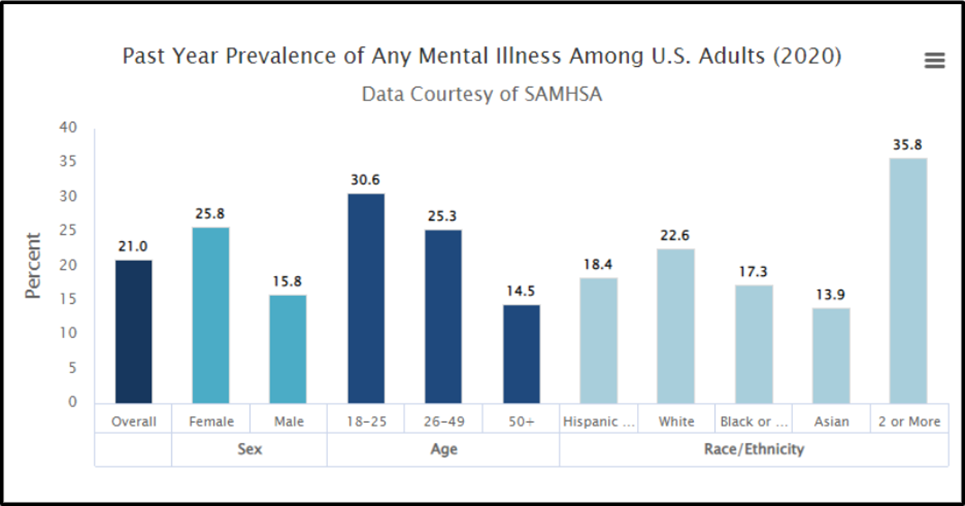

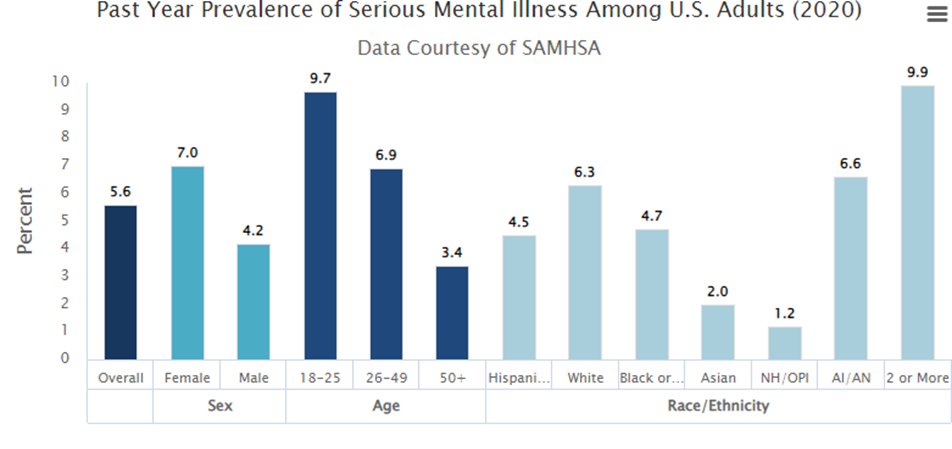

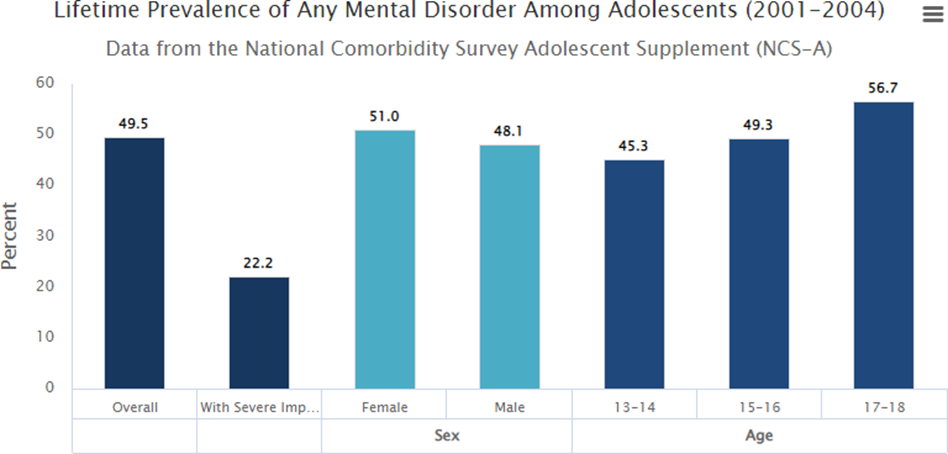

Mental illnesses are common in the United States. Nearly one in five US adults live with a mental illness (57.8 million in 2021) (National Institute of Mental Health 2023). Mental illnesses include many different conditions that vary in degree of severity, ranging from mild to moderate to severe. Two broad categories can be used to describe these conditions: Any Mental Illness (AMI) and Serious Mental Illness (SMI). AMI encompasses all recognized mental illnesses. SMI is a smaller and more severe subset of AMI. Below it shows the prevalence of AMI and SMI among adults in 2020, and the bottom chart shows the rates of mental illness in adolescents. Some group-level differences in this data are important to notice. The prevalence of AMI among women is much higher than that of men. There is a 10% gap between the two groups. Why might this be?

We see several differences between groups of people. For now, we will focus on just one of the bars on this image: the 35.8% of people who experience any mental illness and report as two or more races. We’ll look at two factors that might influence the mental health of multiracial people: legal history and double discrimination, although there are many more contributing factors.

Mental Health and Mental Illness as a Social Problem

We see how America has changed,” describes several demographic trends of “mixing” occurring recently in the United States. People from different races have always had relationships with each other. Sometimes, in the cases of slavery, these relationships were non-consensual sexual violence. The laws against miscegenation, or the mixing of two races, were only overturned at the federal level in the United States in 1967, less than 50 years ago. (Greig 2013). In fact, “the 2000 Census was the first time that citizens of the United States could select multiple racial categories for self-identification apart from Hispanic ethnicity in a census” (Whaley and Francis 2006). The lack of legal, governmental, and systems recognition of multiracial identity is an additional stress for multiracial people.

A second contributing factor to mental health risks for multiracial people is double-discrimination, the concept that you experience discrimination from both of your communities. This popular media article about Kamala Harris quotes Diana Sanchez, a professor who studies multiracial identity: Sanchez says that multiracial people can face what she refers to as double discrimination, where they experience discrimination from both communities they are members of. In Harris’s case, that leads to South Asians saying she’s not South Asian enough and Black people saying she might not be Black enough. “So there’s all these different sources of discrimination that are affecting the development of your multiracial identity and your experience with it, and that can make it hard to navigate,” Sanchez said. (Chittal 2021)

Social Location and Mental Illness Prevalence

Studies show that your social location—your race, class, gender, and sexuality—influences whether or not you develop a mental illness. Our social environments—the way we were socialized as children to be men or women, and the privileges and disadvantages granted by our race, class, and birth sex—all contribute to rates of mental illness. This does not mean that a particular person is more or less likely to get a mental illness but that the rate of mental illness in a particular social group is influenced by that group’s location in the social structure.

We will focus on the different prevalence of serious mental illness between women and men. Worldwide, women are more likely than men to experience mental health issues (Andermann 2010). In the past, social scientists commonly concluded that women are more emotional than men. Today, we consider other factors. In the optional article, Culture and the Social Construction of Gender: Mapping the Intersection with Mental Health, psychiatrist Lisa Andermann calls us to look beyond individual explanations of women’s mental health and explore structural factors:

Identifying the psychosocial factors in women’s lives linked to mental distress, and even starting to take steps to correct them, may not be enough to reduce rates of mental illness or improve well- the well-being of women around the world. More studies that take into account the interaction between biological and psychosocial factors are needed to explore the perpetuating factors in women’s mental health, explain why these problems continue to persist over time, and suggest strategies for change. And for these changes to occur, health system inadequacies related to gender must be addressed. (Andermann 2010).

When 21% of all adults have a mental illness, and almost half of all teenagers have mental disorders, the condition goes beyond being a personal trouble and enters the realm of a public issue. Biology: Scientists are mapping changes in the brain in much more detailed ways. During adolescence, the brain adds new connections, particularly connections related to executive planning and regulation. Half of adults with mental disorders experience the onset of the disorder by age 14, and 75% of adults experience the onset by age 24 (Kessler 207). Remembering that the human brain is in formation until age 25, these data suggest that experiences during adolescence shape mental health outcomes.

Scientists are mapping brain development in new ways that reveal the importance of the neural networks that are being created in adolescence. An adolescent brain is creating new connections, particularly connections related to planning and regulation. These connections help to stabilize a person’s mental health. Further, if a person’s experience or biology does not map new connections in essential pathways, a person’s mental health may be less stable. Because adolescent brains not only respond to the same experiences as adult brains but develop faster and more extensively, experiences in adolescence may shape the brain’s functioning more powerfully than those experiences in adulthood. Experiences that negatively impact brain development include child and adolescent illness, hormonal shifts, exposures to toxins such as drugs and alcohol, food insecurity, trauma history, and emotional and physical abuse. As we learned, ACEs predict health outcomes. Impact on brain development is one of how childhood trauma impacts adult health outcomes. Specifically, trauma and stress factors negatively impact normal brain development and increase vulnerability to mental or emotional illness.

Other researchers suggest that part of the difference between the two age groups has to do with being able to contact people. Many youths are still connected with school and family, even if they are experiencing mental health issues. Most mental health surveys don’t contact people in residential living, including assisted living, group homes, prisons, or jails. Also, they do not contact houseless people. Because of this, mental health issues in adult and senior populations may be significantly under-reported (Kessler and Wang 2008). More stress, less stigma: Also, researchers are exploring whether the increase in reporting of mental health issues for teens and young adults is due to experiencing more stressors or experiencing less stigma around reporting mental health concerns.

Conflict in Values

One major conflict in values we see in the social problem of mental health and mental illness is the value of community care versus the efficacy of psychiatric care. Historically, many people with mental illnesses were institutionalized. Many state hospitals provided essential care. People were isolated from their families and communities and significantly stigmatized. Also, because these facilities were often locked, outside oversight was often limited. In 1955, over half a million people were hospitalized (Talbott 2004). Since this high, the institutionalized population has decreased by almost 60% (Yohanna 2013). Some of that decrease is due to a change in values. Talbott writes, “The impact of the community mental health philosophy is that it is better to treat the mentally ill nearer to their families, jobs, and communities” (2004). This perspective humanizes people with this condition. Unfortunately, government funding for community mental health services and other social supports is insufficient to meet the need. Instead of finding wrap-around support, many people who were deinstitutionalized became homeless instead (Pierson 2019).

Socially Constructed but Real in Consequences

Scholars disagree over whether mental illness is real or a social construction. The predominant view in psychiatry, of course, is that people have actual mental and emotional functioning problems. These problems are best characterized as mental illnesses or mental disorders and should be treated by medical professionals (Kring and Sloan 2009). But other scholars, adopting a labeling approach, say that mental illness is a social construct (Szasz 2008). In their view, all kinds of people sometimes act oddly, but only a few are labeled as mentally ill. If someone says they hear the voice of an angel, we attribute their perceptions to their religious views and consider them religious, not mentally ill. Instead, if someone insists that men from Mars have been in touch, we are more apt to think there is something mentally wrong with that person. We socially construct our concepts of mental illness, labeling some people but not others. This intellectual debate notwithstanding, many people suffer serious mental and emotional problems, such as severe mood swings and depression, that interfere with their everyday functioning and social interaction. Other symptoms of mental illnesses include psychosis, which is the loss of contact with reality; hallucinations, which are seeing or hearing things that others cannot; and delusions, which are believing things that are not actually true. Sociologists and other researchers have investigated the social epidemiology of these problems. As usual, they find social inequality (Cockerham 2011).

Unequal Outcomes

Sociologists see unequal outcomes when they examine the prevalence and outcomes of mental illness. First, social class affects the incidence of mental illness. To be more specific, poor people exhibit more mental health problems than rich people. They have higher rates of severe mental illnesses such as schizophrenia, serious depression, and other problems (Mossakowski 2008). However, sociologists are careful not to confuse correlation with causation. Some sociologists believe that the stress of poverty can contribute to having a mental illness. Others think that having a mental illness may increase the chances that the person might be poor. Although there is evidence that both cause poverty, most scholars believe that poverty contributes to mental illness more than the reverse (Warren 2009).

Second, gender is related to mental illness in complex ways. The nature of this relationship depends on the type of mental disorder. Women have higher rates of eating disorders and PTSD than men and are more likely to be seriously depressed. Still, men have higher rates of antisocial personality (a lack of empathy, or psychopathy), disorders, and substance use disorders that lead them to be a threat to others (Christiansen, McCarthy, and Seeman 2022). Although some medical researchers trace these differences to sex-linked biological differences, sociologists attribute them to differences in gender socialization that lead women to keep problems inside themselves while encouraging men to express their problems outwardly through violence (Kessler and Wang, 2008). Women are socialized to talk about their feelings more than men, who tend to be less connected to their feelings. To the extent that women have higher levels of depression and other mental health problems, the factors that account for their poorer physical health, including their higher rates of poverty, stress, and rates of everyday discrimination, are thought to also account for their poorer mental health (Read and Gorman 2010). Mental health is a social problem, although people rarely take to the streets to protest about mental illness.

Social Location and Mental Health

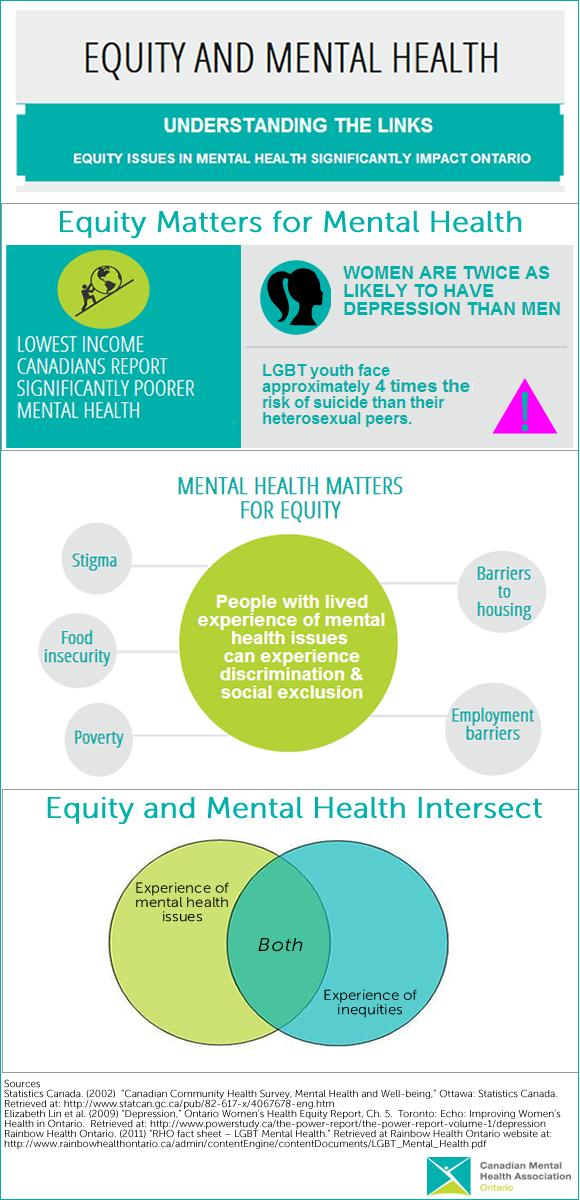

Figure 16 “Equity Matters to Mental Health” highlights the intersectional nature of social location and mental health. In the related report, the Canadian Mental Health Association-Ontario detrimental relationship between equity, mental health, and intersectionality:

- Equity matters for mental health. Due to decreased access to the social determinants of health, inequities negatively impact the mental health of people who live in Ontario. Marginalized groups are more likely to experience poor mental health. In addition, marginalized social determinants of health to the social determinants of health essential to recovery and positive mental health.

- Mental health matters for equity. Poor mental health has a negative impact on equity. While mental health is a key resource for accessing the social determinants of health, historical and ongoing stigma has resulted in discrimination and social exclusion of people with lived experience of mental health issues or conditions.

- Equity and mental health intersect. People often experience both mental health issues and additional inequities (such as poverty, racialization, or homophobia) simultaneously.

Intersectionality creates unique experiences of inequity and mental health that pose added challenges at the individual, community, and health systems levels (Canadian Mental Health Association 2014). Mental health status itself can influence your ability to stay in school, hold a job, or raise a family. And the reverse is also true if you are struggling to put food on the table, keep your kids stable, or stay safe in your neighborhood, you are more likely to have poor mental health.

Race and Ethnicity

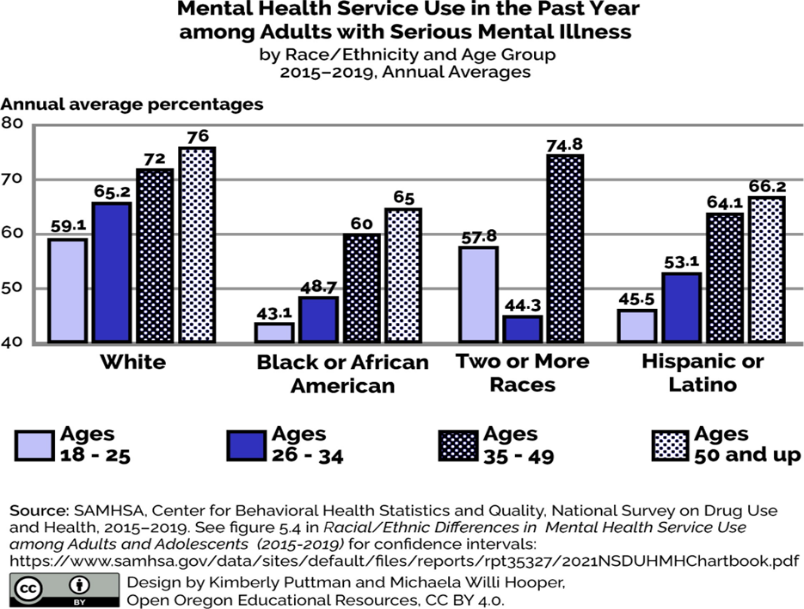

We can also examine the number of unmet needs for mental health services according to race and ethnicity. When we do this, we see that People of Color have more unmet needs than non-Hispanic White people. Black and Brown people have a harder time accessing quality mental health services. When they do receive services, they are more likely to have a negative experience. Some cultures have more stigma around mental health issues than White Americans generally have. This can be a barrier for some immigrants and first- and second-generation Americans to seek services.

For immigrants, mental health providers often lack language and cultural competency skills, which makes the treatment much less effective. Finally, People of Color are profoundly underrepresented in research and clinical trials for new treatments. Mental health researchers often don’t consider the unique experiences of People of Color when they develop new treatment options or medications.

Class Issues in Mental Health Treatment

One of the most consistent findings across studies is that lower socioeconomic groups have greater amounts of mental illness. One of the earliest studies of the sociology of mental health came from the University of Chicago in the 1930s. Sociologists explored whether mental illness caused poverty or whether poverty caused mental illness. The two researchers who led this project—Faris & Dunham—looked at psychiatric admissions to Chicago hospitals by neighborhood. What they found was rather shocking—there was a nine times increased rate of schizophrenia from people who came from poorer neighborhoods, than from more middle-class neighborhoods. The researchers tried to figure out why.

One idea was social selection, the idea that lower-class position is a consequence of mental illness. Mentally ill people would drift downward into lower-income groups or poorer neighborhoods because they couldn’t keep jobs. In addition to considering social selection, they considered social causation, also. In this model, which Faris & Dunham later refuted, the lower class position was a cause of mental illness. The results of this early study came back mixed. At first, Faris & Dunham said that the isolation and poverty of living in the central city created schizophrenia cause. But then, they changed their minds and said people with schizophrenia have a downward drift and move to the central, poorer part of town after developing schizophrenia. Later studies have found that Faris & Dunham’s study was actually trying to tell us that it’s both—cause and effect. Social selection theories and social causation theories can be used to account for the relationship between schizophrenia and poverty.

As our infographic on equity and mental health shows, people with mental health issues can struggle with educational and economic stability because sufficient social support is not in place to support them. Poverty itself can be a risk factor for poor mental health.

Gender

Gender has often been an explanation for the occurrence of mental health and mental illness. While traditional explanations focus on women, as explored in the previous section, newer research focuses on the interactions of nonbinary and gender fluid folx (a deliberately non-binary word) and their mental health.

Unpacking Oppression, Embodying Justice: Patriarchy

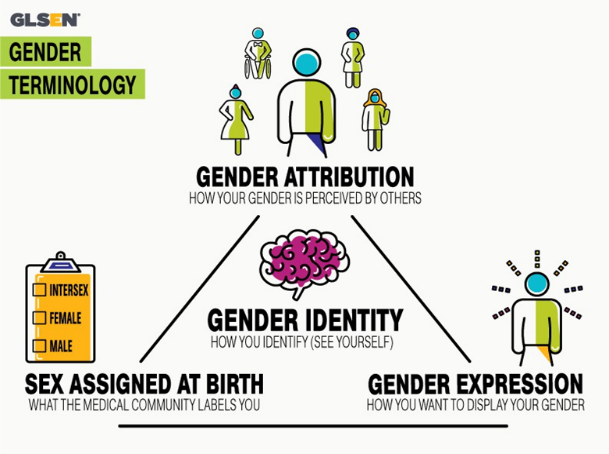

Traditionally, sociologists defined gender as the attitudes, behaviors, norms, and roles that a society or culture associated with an individual’s biological sex. Gender describes the social differences between females and males or the meanings attached to being feminine or masculine. This definition is somewhat outdated because it labels gender as only female or male rather than seeing gender expression and gender identity as a continuum.

The Human Rights Campaign Foundation (HRC) defines gender identity as one’s innermost concept of self as male, female, or a blend of both or neither—how individuals perceive themselves and what they call themselves (Human Rights Campaign 2023). One’s gender identity can be the same or different from the sex assigned at birth. For example, you may know yourself as female, even if your physical body has a penis. Alternatively, you may feel like female or male gender labels don’t fit you at all. HRC further defines gender expression as the external appearance of one’s gender identity, usually expressed through behavior, clothing, body characteristics, or voice, and which may or may not conform to socially defined behaviors and characteristics typically associated with being either masculine or feminine (Human Rights Campaign 2023).

Often, your identity and your expression match. Sometimes, you may choose to wear skirts, glitter, and paint your nails, even if your gender identity is male. Gender, then, is a complex construct. Gender develops throughout life. We may change our gender identity as we age.

Social Location and Mental Health

How sociologists understand gender changes as we listen carefully to people who don’t fit in traditional gender boxes. How each of us “does” gender changes as we become more authentically ourselves throughout our lives. Even though our concept of gender is fluid, our social structures consistently privilege people with a male gender and marginalize people of a female or nonbinary gender.

Patriarchy is a form of mental, social, spiritual, economic, and political organization/ structuring of society produced by the gradual institutionalization of sex-based political relations created, maintained, and reinforced by different institutions linked closely together to achieve consensus on the lesser value of women and their roles. This is a powerful definition, but it is complicated to understand. Think of it this way. Put simply, feminism is the radical idea that women are people. Patriarchy is the social structure and related behaviors that give men power, and oppression women and people of non-traditional gender. As social problems scholars, we want to understand how patriarchy works in a much deeper way.

Leadership is a male role and a source of male power. The third principle, male identification, locates men at the center of what is right and good. We see this principle in action when we use words like all mankind when we mean all people. The fourth and final principle is male-centeredness. In this principle, we focus on and value the activities of men and boys, rather than women, girls, and nonbinary gendered people.

Combining many of these principles in action, the US Soccer Federation only agreed that female and male soccer players should earn equal pay in 2022. For more on this landmark victory, feel free to read The US National Women’s Soccer Team Wins $24 million in equal pay settlement.

Models and Treatments

We will explore the different models of mental health and mental illness. These models come to us from different academic disciplines—psychology, psychiatry, and sociology. All three have something to offer to mental illness and mental health and mental illness.

The dominant models of mental illness are biological, medical, and psychological, and so are important to learn about even in a sociology course! Cultural views and beliefs about mental illness have varied enormously throughout his- tory. For example, ancient humans once believed that mental illness was caused by the influence of evil spirits over the afflicted person. Accordingly, treatments back then involved removing part of the patient’s skull to allow the demon to escape. Later, during the Middle Ages, mental illness was thought to be connected to the moon (hence the term lunacy). Another common belief was that a person with mental illness was being punished by God.

Fortunately, we’ve come a long way since then. However, scientists are still struggling to pinpoint exactly what causes mental illness. Most people, however, agree that mental illness can be influenced by a variety of things, including biological factors, personal history and upbringing, and lifestyle. To help provide a framework for understanding these potential causes, experts have developed several different models, which we’ll explore here.

Biological model

The biological model of mental illness approaches mental health in much the same way a doctor would approach a sick or injured patient. They look for problems or irregularities in the body that are causing the symptoms. Adherents of the medical model believe that mental illness is primarily caused by biological factors such as abnormal brain chemistry or genetic predisposition (McLeod 2023).

Medical model

The medical model of mental illness has proven to be true in many cases. For example, depression has long been linked to deficiencies in certain neurotransmitters (a chemical substance that is released at the end of a nerve fiber), and schizophrenia has been shown to run in families. Science like this forms the basis of psychopharmacology, which is the treatment of mental illness with medication that adjusts the level of neurotransmitters present in the brain. Researchers still do not know what turns on or off the brain/chromosome structures. The result is an impairment of a person’s overall level of functioning. However, critics of the medical model believe that it is too simple because it ignores important social factors in a person’s life.

Psychological model

As you might expect, in the psychological model of mental illness, psychologists look at psychological factors to explain and treat mental illness. For example, they look at attachment theory, which is a theory that examines how you relate to other people. There are over 500 different psychological models of therapy there is a right model for everybody, and a psychologist’s or therapist’s job is to figure out which of those models works for which patient. Of course, psychologists have preferences, and skill sets no psychologist can practice 500 forms of psychotherapy.

Sociological Approaches to Mental Illness

The previous models focus on biology, medicine, and psychology. However, as sociologists, we know that social factors matter. They apply also to mental health. The social determinants of health help us to explain why mental illness a social problem is also. Let’s look more deeply at sociological theories of mental health.

Functionalist

Functionalist sociologists begin to layer social approaches to medical and psychological models. Functionalists look at the function that mental illness and mental health play in society. They look at how mental health functions in a person’s life. To this end, they developed psychosocial and biopsychosocial models of mental illness. One functionalist model of mental illness is called the psychosocial model of mental illness. The psychosocial approach focuses on how individuals interact with and adapt to their environment. Specific factors of interest might include a person’s relationships, past trauma, economic situation, outlook on life, and religious beliefs.

For example, stress both good and bad can affect your mental health. Social scientists pay attention to where these stressful areas are. Starting a new job is in the top three stressful things but most people are happy to start new jobs. Happiness aside, the new expectations, roles, and attitudes you find at your new workplace cause stress. Of course, negative things can also cause stress, and psychologists help people develop resilience against this sort of stress so they can successfully navigate the stressful situation.

Another thing psychologists consider is your social roles. Having conflicting social roles—such as being a parent during COVID-19 and having a full-time job, is a role conflict that can cause stress. There are several kinds of role strain, when one role takes up too much of the time you need to dedicate to other roles or when two different roles compete with each other.

As the name implies, the psychosocial model focuses on the importance of psychological and social factors in informing a person’s mental health. Rather than looking to a person’s brain for clues, a proponent of the psychosocial model of mental illness might look to a patient’s personal history, attitude, beliefs, and life circumstances to better understand their mental illness.

However, the psychosocial model is also limited because it doesn’t take biological or genetic factors into account. To address this, sociologists, psychologists, and psychiatrists have developed the biopsychosocial model of mental illness, which addresses the idea that mental health problems are caused by a combination of biological, sociological, and psychological features.

For example, it can be true that a patient has a biological disposition to mental illness and has experienced trauma that is causing or exacerbating their symptoms. Similarly, many patients have discovered that a combination of psychotropic medication and talk therapy helps address their mental health issues. In fact, many mental health care providers integrate both approaches into a more holistic framework called the biopsychosocial model.

Symbolic Interactionist

Mental illness impacts individuals, so why do sociologists, who study groups, research it? Michaels MacDonald, historian of psychiatry, observed, “is the most solitary of afflictions to the people who experience it; but it is the most social of maladies to those who observe its effects” (1981:1). Mental illness has social and cultural dimensions which compel sociological interest.

Psychiatry generally focuses on the suffering individual while sociologists study the social aspects and implications of an individual’s mental disturbance on friends, family, community, and society. Sociologists ask questions like:

- How can we define and draw boundaries around mental illness and distinguish it from eccentricity or mere idiosyncrasy?

- Who determines what is “normal” difference and what is pathological?

- Who has the privilege to make such decisions? Why? Do such things vary across time and cross-culturally?

- How have societies responded to the presence of those who do not seem to share our common sense notions of reality?

As part of the answer to these questions, the social construction theory of mental illness states that mental illnesses, mental health, normality, and abnormality are all social constructions and are not based on biological reality. One socially constructed concept is the idea of what is normal. People in power say that normal is being happy and productive. If you are not these things, you are deemed “abnormal” or “sick.” The National Alliance for Mental Illness, or NAMI, challenges this idea and argues that people with mental illnesses are indeed “normal,” although they may be different. Differences are to be celebrated, not labeled as dangerous or damaged.

At the same time, mental illness has profoundly disruptive effects on individual lives and on the social order we all take for granted. Mid-twentieth century writings still constitute some of the most provocative and profound sociological meditations on the subject, is perhaps best known for his searing critique of mental hospitals as total institutions. From the late nineteen-sixties through the nineteen-eighties, the intellectual distance and even hostility between sociologists and psychiatrists often seemed to be growing. Within five years of the appearance of Goffman’s groundbreaking book Asylums, the California sociologist Thomas Scheff had authored a more radical assault on psychiatry. Scheff dismissed the medical model of mental illness altogether and attempted to replace it with a societal reaction model, where mental patients were portrayed as victims—victims, most obviously, of psychiatrists (Scheff 1966).

Noting that despite centuries of effort, “there is no rigorous knowledge of the cause, cure, or even the symptoms of functional mental disorders,” argued that we would be better off adopting “a [sociological] theory of mental disorder in which psychiatric symptoms are considered to be labeled violations of social norms, and stable ‘mental illness’ to be a social role.” And “societal reaction [not internal pathology] is usually the most important determinant of entry into that role” (Scheff 1966:25).

During the 1960s and 1970s, the societal reaction theory of deviance enjoyed broad popularity and acceptance among many sociologists. Scheff’s was one of the principal works in that tradition. In the face of an avalanche of well-founded objections, Scheff was eventually forced to back away from many of his more extreme positions. By the time the third edition of his book appeared (Scheff 1999), most of its bolder ideas had been quietly abandoned. Labeling and stigmatization of the mentally ill have remained important subjects for sociologists. This stigmatization of illness is when shame or disgrace is aimed at a person with a physical or mental illness or condition. The idea of stigmatization is powerful, even if few would now argue that they have the significance once attributed to them.

Though the labeling theorists’ skeptical claims have been sharply curtailed, much of the sociological work on mental illness has retained its critical edge. Four major inter-related changes have occurred in the psychiatric sector in the past half-century. The first change is the progressive abandonment of the prior commitment to hospitalization for patients for life when they have serious mental illness. The second change is the rundown of the state hospital sector.

Deinstitutionalization, for example, was initially presented as a grand reform, ironically just as the mental hospital had originally been. From the mid-1970s, however, a more skeptical set of perspectives emerged. Psychiatrists had assumed that the new generation of antipsychotic drugs had been the main drivers of the expulsion of state hospital patients. In reality, it was a political and economic decision by the federal government to close mental hospitals because they were expensive and overcrowded. Also, there was a move toward community mental health, which provides a patient-centered approach, but these services were not sufficiently funded. Also, there are not enough beds in current hospitals and psychiatric wards for the people who need them.

Unfortunately, deinstitutionalization had several unintended consequences, including a rise in homelessness (Mechanic and Rochfort 1990). Another unintended consequence is that the prison system became a de facto asylum system. Approximately half of current prison and jail inmates experience a mental illness. However, treatment there is irregular and insufficient (Bronson and Berzofsky 2017).

In addition, the hegemony, or dominance, of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual (DSM) began to attract attention, with critics examining both the processes by which the successive editions had been produced and the intended and unintended effects of its widespread use. The sources and the impact of the psychopharmacological revolution drew increased interest, with attention paid to both the role of the pharmaceutical industry and changes in the intellectual orientation of the psychiatric profession.

Mental Health Is Social Justice

As the title of this topic suggests, “It’s Okay not to be Okay.” This was one of the themes of the media response to COVID-19 and the related mental health problems people experienced due to the isolation and fear brought on by the pandemic. For example, the 2020 song OK Not to Be OK by Marshmello and Demi Lovato deals with this topic head-on. By the winter of 2020, the CDC reported that up to 40% of Americans reported mental health problems due to the pandemic (Kostic 2020). In conjunction with the White House, the CDC, and Health and Human Services, the Ad Council created a new advertising campaign that discussed coping skills for dealing with the pandemic. Feel free to watch the ad campaign Coping-19.

To explore alternative approaches to addressing this problem, let us examine two programs that increase mental health access to treatment in non-traditional manners. The Crisis Assistance Helping Out On The Streets (CAHOOTS) program in Eugene, Oregon, addresses mental health and drug-related issues integrated into the police and 911 emergency access services system operated jointly by Policeite Bird Clinic and the Eugene police. CAHOOTSs began as an offshoot of the counter-culture movement in Eugene. The organization provided volunteer-operated mental health services to the community. It also presented periodic role-playing seminars to the Eugene police related to managing and defusing mental health-related situations in policing. In the 1980s, the police department began taking advantage of this community initiative, informally referring mental health cases to the CAHOOTS organization to reduce the direct involvement of police in non-crime-related scenarios. CAHOOTS volunteers still offer crisis response services and access to other community services to persons experiencing mental health or drug-related issues.

Following a 2015 lawsuit against the city for excessive use of force and racial discrimination in a fatal shooting of a veteran with PTSD by the Eugene police, the incidents helped focus public attention on Eugene’s response to a mental health crisis. In response, the Eugene city council committed $225,000 of the city police budget to fund the 24/7 availability of the CAHOOTS services and access to the 911 dispatch system. As the CAHOOTS organization began to respond to calls, the delays in responding to issues decreased significantly, to a level of about double the time required for a response by the police. CAHOOTS estimates that in 2021, roughly 17 percent of the calls to 911 in Eugene resulted in a dispatch of a CAHOOTS team reducing the involvement of the official police significantly. Chris Skinner, the Eugene chief of police, commented before the pandemic hit that increasing the number of CAHOOTS teams is a benefit of probability “The less time I put police officers in conflict with people, the less time those conflicts go bad.”

In 2019, Eugene voters approved a payroll tax to bring in $23 million for additional community safety positions. In the initial proposal, two-thirds of this money was intended to go to the police department for additional positions. Reacting to the Black Lives Matter protests, the city council instead redirected that money to community organizations. CAHOOTS received some of that money and benefited from county use of federal CARES Act funding to open a 250-bed homeless shelter in buildings on the Lane County Fairgrounds. The federal funding expired in June of 2021, but talks are in place to expand the use of some police funds to maintain the program, roughly $1 out of every $50 committed to the police budget.

A different approach by the Loveland Foundation addresses resources to communities of color in a number of locations nationwide, including Texas, Georgia, California, Ohio, and New York. The Loveland Foundation was established in 2018 by Rache Cargle in response to a fundraiser for therapy support for Black women and girls. The organization partners with organizations providing culturally competent therapy resources for Black women and girls in the areas where they operate. The organization funds all or part of the costs of access to therapy. Additionally, the organization operates workshops for therapy providers to educate about eating disorders in Black women and girls in partnership with the Renfrew Center for Eating Disorders. The workshops are a six-part series focusing on providing the historical context, etiology, intergenerational trauma, and its impact on body image, assessment, and treatment.

One unusual feature is their approach to building future therapy support resources for specifically People of Color. According to the American Psychological Association, only 17 percent of therapists in the US identify as People of Color, and only 3 percent identify as Black or African American. The Loveland Foundation is investing significant scholarship funding in enabling undergraduate and graduate education for BIPOC to offer therapy to the BIPOC community, including addressing the use of unpaid internships and the lack of dependable mentors to provide support resources to students wishing to address this need. If you would like to learn more about the services of the Loveland Foundation, you can check out their site, The Loveland Foundation.

When we consider mental health, mental illness, and mental well-being, we notice interdependent solutions supporting social justice. Each of us has agency in our mental health and the mental health of our friends and families. We can care for ourselves and each other. At the same time, we experience different rates of trauma, prejudice, and mental illness. We need equity in mental health resources and treatment options. Organizations like NAMI, CAHOOTS, and the Loveland Foundation work to address the systemic inequities in mental health experiences. Working together we can weave interdependent social justice mental resilience and social justice.

Chapter adapted from: “Inequality and Interdependence: Social Problems and Social Justice (Kimberly Puttman et al.)” by LibreTexts is licensed under CC BY.