4 Topic: Death and Dying as a Social Problem

Learning Outcomes

- Analyze the social factors that influence death and dying, such as inequality in life expectancy and the social construction of death.

- Compare and contrast cultural differences in death and dying practices.

- Evaluate interdependent solutions that promote social justice for individuals and communities experiencing death and dying.

We will be exploring the social problems of death and dying. Some of us have lived with a lot of death in our lives. The experience is familiar, even though every death is painful. Some of us have never even thought about death. Please remember to practice good self-care as you walk with us through this material. And, as much as we once knew about the process of dying and death itself, dealing with death during the COVID-19 pandemic brings its own set of challenges.

To put this story in a wider context, over 767 million people contracted COVID-19 worldwide as of August 2023. Nearly 7 million people worldwide died from COVID-19. (World Health Organization 2023). That’s about half the population of the Pacific Northwest or just under twice the population of Los Angeles. Although some people would have died anyway, many of these deaths were unexpected. Sociologists call this pattern excess death, the difference between the observed numbers of deaths in a particular period and the expected deaths for that same period (CDC 2023).

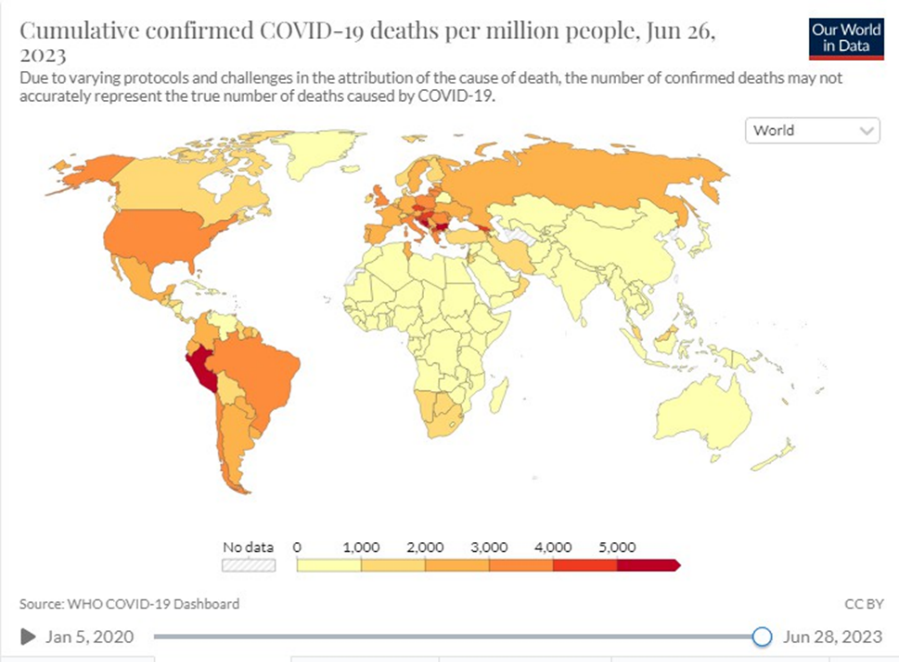

The level of illness worldwide overwhelmed our healthcare system. The amount of unexpected death overwhelmed our end-of-life systems as well. Hospitals in New York and elsewhere needed to park morgue trucks in their parking lots to handle the number of bodies. Spiritual care staff, including chaplains, pastors, ministers, rabbis, and other religious leaders, performed funerals on Zoom and prayed over burials in uncountable numbers. Every country has been impacted by unexpected deaths due to COVID-19. You can see the cumulative death per million people on the map.

As we consider what may be the most personal of all human experiences, death, we also see that death is a social problem. We notice that where you live, and by country, changes the likelihood that you will die of COVID-19. Even by this simple measure, death is also a social problem.

Death and Dying as a Social Problem

“Nothing is certain but death and taxes.” This phrase summarizes some of the wisdom of living in a modern economy. If we think back to the sociological imagination, we know that of course, death is personal. It happens to each of us diversely and individually. However, death is also a social event. Our families, friends, and communities walk through the process with us. We depend on the social institutions of hospitals and hospices and the businesses of more deaths and funeral homes to care for deaths. Even the government must issue death certificates for deaths to be considered valid. In this sense, death is also a social problem.

Beyond the Experience of the Individual

Death is one of the most intimate and personal issues a person will ever confront. What happens to an individual is affected by the social context within which it takes place, but death also has broader social implications. At a micro level of analysis, death, and the dying process involves the loss of social roles and a shift in existing roles. For instance, when a parent dies, you lose someone in the parental role. Older siblings, grandparents, or family friends may need to step in and take on parenting responsibilities. Social relationships are also altered. The loss of a member of our social circle affects all who are part of that social network. As a result of a death, the group dynamics and relationships may need to be renegotiated, and a new shared meaning developed.

At a social institutional level, death and the resulting loss of a worker, a teacher, or a community leader affect institutional processes and shift institutional resources to fill vacated roles. While a single death may have one type of impact, numerous deaths may have a more immediate and significant societal impact. The COVID-19-related workforce issues disrupted the flow of goods and services worldwide.

Conflict in Values: Right to Die

All human societies must answer the profound questions of who lives and dies. We discussed the conflict in values related to who lives when we discussed reproductive justice. We also see a conflict in values in talking about who dies. Who gets to decide who dies? What criteria or values do people use to make this decision? This conflict in values is expressed in right-to-die laws. These right-to-die laws are the laws that allow a person who suffers from a terminal disease and meets the required criteria to choose to end their life on their terms. They provide an option for eligible individuals to legally request and obtain medications from a physician to end their lives in a peaceful, humane, and dignified manner. As of 2023, only 10 states and the District of Columbia have a Death with Dignity law.

In recent decades there has been a growing movement to ensure that individuals have the autonomy and agency to control their own end-of-life decisions, including the right to die. With medical professionals’ advice, the government sets standards, accepted practices, and legal statutes concerning end-of-life options. These regulations and standards may conflict with the personal preferences of those who are in the dying process.

This highlights a fundamental question, “Who has the ultimate right to decide how and when an individual’s life ends?” Those working for the passage of so-called “right-to-die” legislation (also referred to as physician-assisted suicide or physician-assisted death) assert that individuals should be able to decide how much pain, suffering, and debilitating symptoms at end-of-life they should endure.

The first right-to-die law in the United States was enacted in Oregon in 1997. Oregon’s Death with Dignity Act (DWDA) allows a terminally ill individual to end their own life with a self-administered lethal dose of medication prescribed by a physician for that purpose (Oregon Health Authority 2022). The Oregon law sets out a very structured procedure with specific requirements and criteria that must be met for an individual to utilize this option. Generally, you must be able to make decisions for yourself, and two physicians must agree. Those who oppose this type of legislation express fear over a lack of oversight. They cite concerns that the final decision to end one’s own life will be made by others on behalf of those who may be too ill to speak on their behalf. Some fear the normalization of physician-assisted death to the point that patients will feel responsible for relieving the burden their care places on their loved ones. And many believe it is the job of physicians to alleviate suffering, not the role of the patient to decide.

Beliefs grounded in a sanctity of life orientation strongly emphasize the basic duty to preserve life. This perspective is often grounded in cultural and religious tenets that explain life as being a sacred gift granted to humans accompanied by a requisite responsibility to care for the body. Such an orientation may lead to a preference for using all available medical options to live as long as possible.

Alternatively, others may focus more on the quality of a person’s life. A quality-of-life perspective argues that when life is no longer meaningful, the obligation to preserve life no longer exists. Although medical technology may be able to extend life, the human experience of living is more important than simply keeping the body medically functioning. From this orientation toward life, the emphasis is placed on the ability to live with dignity and purpose. Decisions concerning the use of end-of-life medical interventions are shaped by the intentional consideration of the distinction between the quantity of life and the quality of that life.

Inequality in Life Expectancy

Although death is an inevitability of the human condition, mortality rates vary based on social location. When and how a person dies is more than just the outcome of individual genetics and human physiology. Life expectancy and cause of death are also affected by the social determinants of health, such as access to healthcare, quality of life indicators, geographic location, and socioeconomic variables. Differential patterns in life expectancy and death rates based on gender and race/ethnicity are affected by broader social issues and systemic inequalities.

Social institutional features involving work, family, social class, healthcare, and social construction of gender role expectations contribute to the ongoing differential life expectancy, the number of years a person can expect to live, based on an estimate of the average age that members of a particular population group will be when they die (Ortiz-Ospina 2017). When we look at life expectancy based on gender, we see a difference. Males are predicted to live only 76.3 years on average, while females are expected to live 81.4 years on average (National Center for Health Statistics 2021).

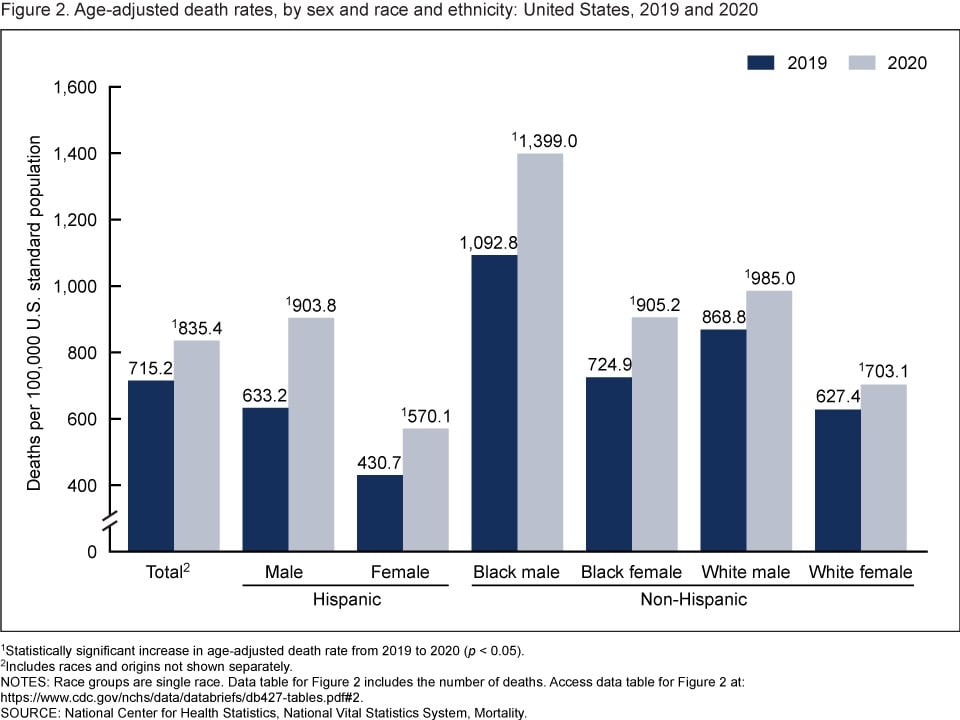

Comparative death rates based on race and ethnicity also reflect systemic inequalities in social systems and people’s social experiences.

The impact of social inequalities is also evident during significant catastrophic events that challenge society, such as the COVID-19 pandemic. With the emergence of a new virus, this medical crisis strained social institutions and fundamentally interrupted previous patterns of social activity. Any one of us could get COVID-19, but the probability of contracting the virus and the likelihood of death from the infection are affected by social factors. Many of these social risk factors disproportionately impact people based on social location indicators such as race, ethnicity, and social class.

| Race/Ethnicity | Number of Cases | Percent of Cases | Number of Deaths | Percent of Deaths | Percent of CA Population |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Latino | 3,171,021 | 42.5% | 42,360 | 41.9% | 36.3% |

| White | 2,042,907 | 27.4% | 35,688 | 35.3% | 36.8% |

| Black | 313,576 | 4.2% | 6,919 | 6.8% | 6.5% |

| Asian | 1,122,993 | 15.1% | 15,105 | 14.9% | 15.4% |

| Other | 339,452 | 4.6% | 4,525 | 4.5% | 4.7% |

| Total | 7,453,970 | 100.0% | 101,212 | 100.0% | 100.0% |

As you look at this table, you may want to start at the last column. This column reflects the percent of California’s total population for a particular group’s race and ethnicity. If race and ethnicity did not influence the rate of catching COVID-19 or dying from COVID-19, you would expect that columns Cases (column 2) and Deaths (column 4) would match the last column. They do not. Instead, we see that White, Asian, and multi-ethnic people have a slightly lower-than-expected death rate. People of all other races and ethnicities have a slightly higher death rate. When you consider what you learned about why this is true for health, you can apply those learnings to understanding the consequences of social location on death.

The Social Construction of Death

Determining when a death takes place seems straightforward and obvious. When a person’s body ceases to function, death has occurred. But as one delves deeper into the details and specifics, that task becomes far more complex. Historically, there have long been accounts of people who were determined to be dead when, in fact, they were still very much alive. Although not common, such instances were often a result of shallow breathing or faint heartbeats that went undetected. Advancements in medical technology address this possible problem. At the same time, they introduce new challenges in determining when death occurs. Modern medicine’s ability to artificially keep people alive raises new and difficult questions in determining when death occurs. Therefore, society found a need to clearly define what determines death, delineate the criteria to be used to establish that death has occurred and develop a process to socially recognize and certify death.

Clinical Death

The customary method of determining death has centered on the cessation of basic vital signs of life – the absence of breathing and a heartbeat. However, advancements in new technology have raised new issues and challenges in using these conventional methods for establishing death. The use of advanced life support systems, such as ventilators, respirators, and various methods of cardio-pulmonary support, can now artificially support life for long periods of time. In these cases, a person can be kept “alive” through mechanical means for days, months, and in some cases, years. While in this state, do we say that the person is alive, or that the person is dead?

With the ability to keep a person breathing and the heart beating through artificial means for long periods of time, the medical community turned to the concept of brain death to determine death. Based on the work of the 1968 Harvabrain Death School Ad Hoc Committee, brain death, or what became known as the “whole-brain” definition of death, involved the following criteria: the absence of spontaneous muscle movement (including breathing), lack of brain-stem reflexes, the absence of brain act brain death the lack of response to external stimuli. This criterion for brain death is used to augment the customary use of vital signs when they may be ambiguous.

Legal Death

The definition of death affects many aspects of our daily lives. The death of an individual often triggers government laws that regulate issues directly related to how the body of the deceased is handled and the options for the final disposal of the corpse. Issues arising after death may also require some type of official government documentation verifying a death has occurred. A government-issued death certificate with verified information as to the date, place, and in some cases, the cause of death is needed to execute wills and inheritances, file necessary taxes, assess any civil and criminal liabilities, and a host of other legal issues regulated by the government. With the broad-based acceptance of the medical criteria for death, legislative discussion ensued to develop a standardized, legal means for determining that a death has occurred. Efforts focused on updating the legal standards used to determine death that closely aligned with the criteria being used by the medical community.

Social Death

Social death involves the loss of social identity, loss of social connectedness, and loss associated with the disintegration of the body (Králová 2015). This can be marked by a specific event, such as biological death. But it can also involve a series of changes, such as the loss of the ability to take part in daily activities, the loss of social identities, and/or the loss of social identity during end-of-life and the dying process. When there is a social determination of death, a person’s place in society changes. There is a shift in their social status that denotes a separation from society and community. Establishing when social death occurs signals others as to the expected adjustments in social interactions.

Social death can change social role expectations, social status, and social interactions. When a person is dying, they may no longer be able to fulfill their social roles. For instance, a mother or father may no longer be able to care for the children. The children may need to become care providers for the parents. Adult children may become the care provider for an aging parent. The meaning of friendship expectations changes and social interaction within community or work settings is altered or severed.

After biological death, the status transition of the deceased from the world of the living to the spiritual realm or the world of their ancestors is often denoted by funeral rituals. Socio-cultural beliefs, values, and norms form the basis for the determination and meaning of social death. In the US dominant culture, the meaning of social death may be directly linked to the absence of medical/ biological indicators such as breathing, heartbeat, brain-based reflexes, and processes that then lead to various funerary rituals.

In other cultural belief systems, biological death is only one aspect of determining social death. For the Toraja people of Indonesia, social death does not come until the body leaves the home. They often keep the body of the biologically deceased in the home as an ongoing social member of the family and community for weeks, months, or even years. During this time, the person is perceived as being sick or in a prolonged sleep. They are fed and bathed, and their clothes are periodically changed. They are talked to, hugged, caressed, and moved to various settings to ensure they are included in family and community activities. The removal of the body from the home and completion of funerary rituals denotes the change in social status and social determination of death (Arora 2023; Seiber 2017).

Interdependent Solutions

The final characteristic of a social problem is that it requires both individual agency and collective action to create social justice. When we apply this characteristic to the experience of death and dying, we can change both the individual willingness to talk about death. We can also create communities that collectively support the experience of dying. Many of us are afraid to even talk about dying. However, this isn’t the only way to approach death. Instead, we can be open to learning about death and talking about it. We can be death-positive. Death positive doesn’t mean that we want to die now. Death positivity means that we are open to honest conversations about death and dying. It is the foundation of a social movement that challenges us to reimagine all things tied to death and dying (Lewis 2022).

One of the ways to have individual agency is to have “the conversation.” In this conversation, you can talk to your parents, your children, your partner, or your friends. You can talk about what you want at the end of life, what you think will happen when you die, how you want your funeral to be, or what gives meaning and value to your life. By having these conversations now, you begin to prepare for the end of your life or the end of life for those you care about.

You can also participate in a Death Cafe. A Death Cafe is a social gathering, usually with tea and cake, where people talk about death. The question may range from, “What do you want to be remembered for?” to “What is the best funeral you ever attended?” Because people talk about death, they support each other and are more prepared to deal with it when it happens (Death Cafe N.d.). Having the conversation and attending a death cafe are acting at an individual and community level. However, death positivity is also a social movement. Rather than marching with signs, activists are creating compassionate communities. People are forming communities that care for each other, whether physically living together, meeting regularly, or connecting online. Hospice Palliative Care Ontario describes it this way, “A Compassionate Community is a community of people who feel empowered to engage with and increase their understanding about the experiences of those living with a serious illness, care” (Hospice Palliative Care Ontario 2019). At these individual, community, and institutional levels, we see action creating social justice. We’ll examine many more interdependent solutions as the chapter continues.

Inequality in End of Life and Death

We will explore three ways to understand inequality in the social problem of death and dying. First, we examine the sociological concept of life course, which helps us understand the expected paths of our lives and the differences in power and privilege that occur at each stage. Then, we look more deeply at inequalities based on cultural death in a White US culture “does” death in culturally specific ways. People from Latinx, Black death Indigenous cultures have other ways of understanding end-of-life, death, and life after death. When cultures collide, we see inequality. Finally, we look at end-of-life. In this section, we specifically highlight the challenging social location of being rural. Ruralness itself contributes to shorter life expectancy. We’ll look at why that is. First, let’s find out more about the relationship between power and age.

Unpacking Oppression, Living Justice

Sociologists and other social scientists study the human life course or life cycle to make sense of these questions and many more. As human beings grow older, they go through different phases or stages of life. It is helpful to understand aging in the context of these phases. A life course is the period from birth to death, including a sequence of predictable life events such as physical maturation. Each phase comes with different responsibilities and expectations, which of course, vary by individual and culture.

Inequality in End of Life and Death

The life course in Western societies often includes preconception and pregnancy, infancy, childhood, adolescence, adulthood, and old age. Children love to play and learn, looking forward to becoming teenagers. Teenagers, or adolescents, explore their independence. Adults focus on creating families, building careers, and experiencing the world as independent people.

Finally, many adults look forward to old age as a wonderful time to enjoy life without as much pressure from work and family life. In old age, grandparenthood can provide many of the joys of parenthood without all the hard work that parenthood entails. For others, aging is something to dread. They avoid it by seeking medical and cosmetic fixes. These differing views on the life course are the result of the cultural values and norms into which people are socialized. In most cultures, age is a master status influencing self-concept, as well as social roles and interactions.

You may also experience changes in power and privilege as you move through life stages. Young children, as you might expect, have little power. They depend on others to care for them. When a person turns 18 in the United States, they can vote, which is a level of power and privilege. As people move from adulthood to senior citizens, they may experience more frequent ageism, which is discrimination based on age.

Often, your power and privilege decline as you age. For example, sometimes older workers are laid off first, right before they reach retirement age so that companies don’t have to pay full retirement benefits. Older people aren’t hired for jobs because hiring managers assume that they don’t understand technology or won’t be able to keep up with the demands of the job. In an intersectional example, Black elders often can’t retire or can’t retire well because of the Black wealth gap. Because of racism in employment and housing Black families (and other families’ wealth) cannot accrue generational wealth at the same rate as White families (National Partnership for Women and Families 2021). Therefore, they have less to fall back on when it comes to getting the care that they need during retirement, end of life, and dying.

Also, sociologists see a connection between ageism and death and dying. When people fear death and dying, they don’t want to interact with people who are aging or at the end of life. When they worry about dying, they are more likely to be ageist (Banerjee, Brassolotto, and Chivers 2021), discriminating against people as they age or enter their end of life. For example, a doctor or caregiver might assume that an older person can’t make their end of life decisions based on their chronological age. However, age is only part of the picture. Physical health, mental health, and cognitive capacity all play a role in whether a person is capable of making decisions for themselves (Kotzé and Roos 2022).

As we look at the life course, related more specifically to death and dying, professionals use this model in two ways. The first way helps us understand what constitutes a good death good medicine defines a good death as one that is free from avoidable death and suffering for patients, families, and caregivers in general, according to the patients’ and families’ wishes (Gustafson 2007). Albert Albert McLeod is a Status Indian with ancestry from Nisichawayasihk Cree Nation and the Metis community of Norway House in northern Manitoba. He is an activist and Two-Spirit leader.

When children die, for example, grief is particularly challenging in part because their death is unanticipated and not part of the normal life course. When people who are poor die of diabetes or heart disease as young adults, this is also not a good death because these deaths could have been prevented. Medical professionals also integrate this idea of a good death into their models of health and illness. This infographic is intended for doctors, so it is very complicated. However, if you examine it piece by piece, you will find that we have covered most of these ideas in this book. The infographic helps to synthesize our knowledge.

The circles on the left side represent the social ecology model. A person’s health is impacted at the micro level of individual interactions to the macro level of the laws and policies that create or change structural inequality. People who talk about racial environmental justice might notice how neighborhood exposure to oil or coal burning would impact health outcomes.

The Exposome is the equivalent of Adverse Childhood Effects (ACEs) or the protective factors. The chart maps resilient heath to less health during the aging process. It also shows how the likelihood of illness or death changes depending on social factors. Finally, the chart displays how health and illness may unfold over the life course, depending on social and individual factors. The concept of life course helps sociologists understand how a “good life” and a “good death” unfold for people from a particular culture. When a life or a death does not unfold that way, sociologists can explain why. Social problems scientists can then propose action. Activists, community members, and governments can act or choose not to act to support good living and good dying for everyone.

Cultural Differences in Death and Dying

One of the ways we can think about inequality in death and dying is to consider cultural differences. Think for a minute about the last funeral you attended. For some of you, this may have been a recent experience. Others of you may never have attended a funeral. However, when we examine how people from different cultures think about and do death and dying, we notice many differences.

In dominant White culture, there is often a funeral. People come together to pay their respects to the dead person. The body of the dead person may be present in a casket, or a cremation may occur. People may also attend a viewing or wake, where they can sit with the family and the body to pray or say goodbye. There may be a burial of the body or placement of the cremated remains in a columbarium. Finally, the process may end with a memorial service or a celebration of life, depending on the wishes and beliefs of the person or their family.

This pattern is very common. We also notice three themes related to death and dying in dominant White culture. The first is the denial of death. We don’t often talk about death, prepare for death, or talk about a person who died (Hughes 2014). Although the denial of death is not unique to US culture, the dominant US cultural norm is that being young and beautiful is the right standard. We live as if we will stay young and healthy forever.

The second element of death and dying in the dominant culture is that death and dying is a big business. It costs money for the casket, for embalming the body, the cremation, the rituals, the burial plot, the mausoleum, or columbarium, the flowers, the food, and all of the things associated with the funeral rites. Journalist Jessica Mitford drew attention to this problem. She wrote an article in “The Undertaker’s Racket” for the Atlantic Monthly magazine in 1963. In it, she details all of the people and all of the costs of a traditional US death. At the time of the article, she estimated that the funeral business was a 2-billion-dollar industry in the US (Mitford 1963:56). As of 2023, the funeral industry makes over 20 billion dollars annually (Marsden-Ille 2023). Dying is a big business.

Finally, the dominant White culture leaves very little space for grief. Although bereavement leave exists, it is often short and unpaid. In dominant White culture, people often talk about “getting over” someone’s death as if the grief will go away at some point. It is not common to sit in prayer for several days or to restrict your activities to allow space for grief. However, this way of dying, death, and grieving isn’t the only way. We’ll illuminate inequalities in death and dying by exploring the Day of the Dead/Dia de los Muertos in Mexican and Mexican American culture, RIP T-shirts from the Black community, and current practices in two Indigenous communities. We will use qualitative data, or stories, to do this exploration.

Because we are using stories, we don’t have numbers to demonstrate the inequality present between dominant and non-dominant cultures. However, doing death differently than traditional White culture requires explaining what you need and insisting that you get it activities of resistance that take energy and focus. This additional load is an example of inequality in action.

Before we begin, let’s look at another social location: religion. As you might expect, religion has a lot to do with how we go about death and dying.

Unpacking Oppression, Believing Justice

How people deal with death and dying is often related to their religions and spiritual beliefs. Religion is a personal or institutional system of beliefs, practices, and values relating to the cosmos and supernatural. This definition has two key components. First, people experience religion as a personal set of beliefs and practices. Second, religion is a social institution, a structure of power with hierarchies, doctrines, practices, and beliefs. The religion you belong to is often included when sociologists discuss power and privilege. In the United States, the dominant religion is Christianity. About 64% of Americans are Christian, and the number is dropping (Pew Research 2022). However, Christian privilege is embedded in our society in other ways. For example, our Pledge of Allegiance contains the words, “One nation under God.” Our national holidays include Christmas, a holiday that is only celebrated in Christianity. We most often swear oaths for public service or juries on the Bible, the holy book of Christianity. Recognized churches that closely match the Christian pattern get tax breaks. What other examples can you think of?

Other religions and spiritualities are non-dominant, even though the number of people who are not Christian is rising. Except for Judaism, non-Christian religions like Hinduism, Buddhism, Islam, and others are growing. Additionally, people who identify as “None” or have no religious affiliation will be many people in the US by 2070 (Pew Research 2022). While estimates that far in the future are somewhat unreliable, the number of “Nones” is growing. These differences in religious power and privilege drive inequality in death and dying. Differences in religious practices around death and dying also create conflict. In some religions, for example, it is essential to cremate the body. In others, only burial will work.

Cultural Differences – RIP T-Shirts and Social Justice

When we consider grief and social justice, one of the privileges that wealthy, White people have is time to grieve and resources to have an expensive funeral. In Black communities, on the other hand, grief is disenfranchised. This disenfranchised grief is “grief that is unacknowledged and unsupported both within their sub-culture and within the larger society” (Bordere 2016). Bordere describes this grief: African American youth, for instance, who reside in urban areas are often disenfranchised grievers. Many African American youth cope with numerous profound death losses related to gun violence and non-death losses, including the loss of safety…[these youth are often inappropriately described as desensitized. Consequently, these losses are dealt with in the absence of recognition or support for their bereavement experience in primary social institutions, including educational settings, where they are expected to continue in math and writing as if a loss has not occurred (Bordere 2016).

As a partial response to disenfranchised grief, RIP (Rest in Peace) T-shirts have become part of the funeral rites in Black communities. Dr. Kami Fletcher is the aunt of an African American man who was murdered. Further still, RIP T-shirts allow room for healing by metaphorically filling the void of the loved one’s absence, serving as a second skin to keep him close, and even allowing mourners to fill out the imprint he left, with our own image, (Fletcher 2020). These shirts are also worn after the funeral itself, bringing the presence of the loved one to birthday parties or other family events.

They also become a call for justice because they remind people of the importance of the person’s life. They call out White supremacist violence by both naming and picturing the person who was murdered: From Mike Brown and Sandra Bland to Willie Oglesby, Jr., and Breonna Taylor, and George Floyd, Black bereaved family members politicize their grief in ways that highlight what caused the death as well as use it as a tool to fight for justice. As a walking memorial, the RIP T-shirt is a reminder of the life cut short by injustice. It is a reminder that we have not forgotten and that we won’t forget. (Fletcher 2020).

Wearing RIP T-Shirts becomes another way to “say their name”, to make their name visible, ensuring that the consequences of racial violence are obvious. If you would like to learn more about this memorial proactively, you can read Fresh to Death: African Americans and RIP T-Shirts.

Rural Challenges

What does it mean to be at the end of your life? Common sense would say that the end of life is the period before you die. However, none of us know when we will die. How, then, can we understand when the end of life happens? Researchers depend on two definitions. First, end-of-life is defined by Medicare and Medicaid as a person who is in a six-month or less period before their death. The government uses this definition to decide who qualifies for hospice, particularly when the government is paying for the care.

A second definition focuses on the end of life as a physical process. End of life is the period preceding an individual’s natural death from a process that is unlikely to be arrested by medical care (Hui et al. 2014). The end of life is a fertile ground for social problems. End-of-life decisions raise issues of culture, choice, and values. End-of-life options also vary depending on where you live or how much money you have. Let’s look at the case of rural living.

We introduce the social location of being rural. Social locations such as age, gender, socioeconomic status, and geographic locality affect all aspects of a person’s life. The variability in access to resources and services based on these factors has a significant impact on the dying experience. One social location that matters is geography. People in urban areas and cities tend to have access to more services. To be rural means to live in areas that are sparsely populated, have low housing density, and are far from urban centers (US Census Bureau 2017). US rural populations tend to be older, have higher mortality rates, be more likely to suffer from chronic diseases, and be disproportionately poorer than urban populations (Rural Health Information Hub 2022).

Palliative Care

Death is an unavoidable event in the life course. We are born. Eventually, we will all die. But with the advancements in modern medicine and its ability to manage disease and prolong life, dying has increasingly become an elongated process rather than a sudden specific event. The dying process is now often the result of chronic disease and/or age-related physical decline that can be accompanied by pain and distressful symptoms. Palliative care is often used to improve the quality of life and relieve pain and suffering during end-of-life care. As a treatment strategy, palliative care is specialized medical care for people living with serious illnesses and medical conditions (Definition of Palliative Care N.D.). The focus is on anticipating, preventing, and treating physical, psychological, and emotional pain and relieving symptoms. Rural populations are generally older and poorer than urban palliative career palliative care for palliative care, but they have less access to palliative care (Rural Health Information Hub 2021). Data also indicates that caregivers for the medically fragile who live in rural areas often spend more time providing care and are more likely palliative care of people than in urban or suburban areas. This is especially concerning considering the role palliative care programs can play in supporting those who provide daily caregiving and support for loved ones (Center to Advance Palliative Care 2019).

Readily available access to palliative care has advantages for the patient, those who provide daily care, and the healthcare system. Community-based palliative care programs lower healthcare costs and reduce the need for hospitalization (Weng, Shearer, and Grangaard Johnson 2022). Early diagnosis of care needs and promptly addressing medical needs before hospital care is needed provide obvious benefits for the patient. The availability and accessibility of support services for care providers are also critical to the overall well-being of the patient and the caretakers. In addition, minimizing hospital visits helps bring down overall medical costs and conserves system-wide medical resources at a time when the healthcare system is struggling to control escalating costs.

Rural areas face disproportionate barriers in providing palliative care options. Financially, the sheer volume of patients in urban areas is better able to support the resource allocation needed for hospital and community palliative care programs. Larger patient numbers can financially support the viability of healthcare teams specifically designated and trained to provide palliative care. However, rural areas lack sufficient patient numbers and the necessary medical resources to maintain palliative care programs. These areas are hindered by geographically dispersed patients, significant travel and driving time, the lack of rural hospitals and medical specialists, and the difficulty in recruiting and retaining trained healthcare providers (Weng et al. 2022).

Nursing Care and Home Health Care

The scarcity of nursing care facilities and hospice services in rural areas poses barriers to accessing end-of-life care assistance with medical and personal needs. Nursing care facilities (sometimes referred to as nursing homes) are residential centers designed to provide health and personal care services for those who can no longer care for themselves. These facilities provide a broad array of services dependent upon the specific focus of a facility. Levels of service can range from assisted living settings where residents may need assistance with meals, help with medication, and housekeeping to skilled nursing care facilities where the focus is more on medical care, including rehabilitative services (e.g., physical, occupational, and speech therapy), and complete support with daily activities. These facilities can be essential end-of-life options, but for rural residents, they are often not available. Rural nursing care facilities face many of the same challenges as rural palliative care programs. Rising operational costs due in part to the lower number of patients, distance to resources, and difficulty in finding and retaining trained staff have resulted in a high rate of nursing facility closures across rural America. Rural residents who must often leave their community, family, and friends to access these services face the stress of relocation and isolation because of less contact with loved ones.

When end-of-life health care can be delivered to a patient’s home, it can be less expensive, more convenient, and just as effective as services provided in hospitals or nursing care facilities. However, there is limited access to these services in rural areas, where the service may be based out of cities 50-100 miles away and have limited openings or long waiting lists to enroll. In many instances, there are no options available for specialized medical needs, occupational or physical therapy, or mental health support. To help fill this service gap, telemedicine is increasingly feasible. Research indicates that the use of telemedicine can improve access to healthcare professionals for patients at home. Its visual features allow genuine relationships with healthcare providers (Steindal et al. 2020). However, for rural residents, limited cellular coverage and internet access are barriers. Any cost savings to the patient and the health care system may be far less than what is needed for investment in extending the needed technological infrastructure.

Hospice

Hospice programs provide an important option for end-of-life care. Hospice is specialized health- care for those approaching end-of-life. Hospice focuses on the quality of life and comfort of the patient and supports the patient’s family. The focus of hospice care is not to cure disease or medical conditions. Instead, the goal is to support the patient and their loved ones while facilitating the highest quality of life possible for whatever time the patient has left. To qualify for hospice services, a physician or primary healthcare provider must verify that the patient is terminally ill with 6 months or less to live. A patient’s enrollment can be extended as many times as necessary to support a patient until the end of life. A patient can disenroll whenever they choose or request re-enrollment at any time. The focus within hospice programs is on reducing pain and keeping the patient as comfortable as possible.

The broad-based approach to addressing overall well-being during end-of-life includes attention to physical, psychological, social, and spiritual needs. To address these needs, a hospice team can involve doctors, nurses, and other health care providers as needed, as well as social workers, counselors, and volunteers. Depending upon patient preference, hospice programs may include access to options such as aromatherapy, touch and massage, art therapy, music therapy, and pet therapy. These complementary services can help with pain management and psychological well-being and contribute to the patient’s comfort and quality of life (Hospice Alliance N.d.).

Although hospice programs are increasingly available nationwide, less than 20% of hospices operate in rural areas. Rural hospice programs face many of the same barriers as the other end-of-life care options discussed above. Due to lower patient numbers, staffing shortages, high staff turnover, and long driving distances and time, they are financially vulnerable and have limited services. This is further complicated by a common lack of available family member caregivers, which is essential to the home-based hospice option. Adult children or other caregivers often live far away, making it difficult for the dying patient to be cared for by a family member and live out their life in their home. Although quality end-of-life care can take many forms, rural residents have less access to needed services during the process of death and dying. The social location of rural is a unique location of oppression.

Dying Well is Social Justice

As we look at the complex issues related to death and dying, we see that the question of who dies when is complicated by privilege, oppression, and difference. At the same time, we can take interdependent action to increase social justice for people who are dying and their families. We already talked about the community actions of death cafes and conscious communities. We discussed changes in the laws related to the end of life and the right to life. In this section, we learn about three additional ways that people are taking interdependent action: POLSTs and Advance Directives, Green Burials, and Last Words.

| POLST | Advance Directive |

|---|---|

| Medical Order to a doctor | Legal document |

| A health care professional completes the form | An individual completes the form |

| Is a specific Medical Order | Contains general wishes about treatment |

| A copy is in the patient’s medical record | May not be in the patient’s medical record |

| Was created in 1990 by Oregon Health and Sciences University | Began in 1967, as part of a living will |

| Oregon POLST | Sample Advance Directive |

The state of Oregon is once again an innovator. In the early 1990s, healthcare professionals and the state legislature created the POLST or Portable Orders for Life-Sustaining Treatment®. The POLST allows patients to describe what measures they want doctors to use to sustain their lives. These orders are useful when patients are too sick to speak for themselves. The POLST form is in addition to an advanced directive, a legal document that states a person’s wishes about receiving medical care if that person is no longer able to make medical decisions because of a serious illness or injury. An advance directive may also give a person (such as a spouse, relative, or friend) the authority to make medical decisions for another person when that person can no longer make decisions. Unlike an advance directive, the POLST focuses on what a doctor can or cannot do for the patient, including providing CPR or assistance with breathing. The POLST process is now widely used in all US states, although state regulations vary (National POLST N.d.).

Green Burial

In the United States, until the 1930s, most people died at home. Their loved ones took care of their body. They were buried in-home or city-owned cemeteries. After this time, however, many states required trained morticians to report the deaths, embalm the bodies, and bury them in cemeteries with caskets. Often, these caskets were covered in cement, preventing the normal decay of the body. This style of burial adds toxic chemicals to the environment, risking the health of funeral workers. It also contributes toxins to the cemeteries. As an alternative, eco-death activists agitate for green burials. A green burial is a way of caring for the dead with minimal environmental impact (Green Burial Council. N.d.). This aids in the conservation of natural resources, reduction of carbon emissions, protection of worker health, and the restoration and or preservation of habitat. If a body is buried without these chemicals in a wooden box, the decomposing body can eventually nurture plants.

Last Words Project: Art as Activism

In addition to implementing new laws and policies related to end-of-life, and new options for funerals and burials, one woman is creating new alternatives for expressing grief. Crystal Akins is an arts activist, musician, spiritual director, and death doula. In the Last Words Project, she united people with words and music to create support for the dying and celebrate the dead. In these interdependent actions changing laws and policies, providing new ways to deal with bodies, and using art and song to create change we expand the possibilities for social justice for people who are dying, their families, the dead, and our ancestors.

Chapter adapted from: “Inequality and Interdependence: Social Problems and Social Justice (Kimberly Puttman et al.)” by LibreTexts is licensed under CC BY.