2 Topic: Problems Associated with Drug Use

Learning Outcomes

- Understand the various health, social, and legal consequences associated with drug use and abuse.

- Analyze the impact of drug addiction on individuals, families, and communities.

- Identify effective prevention and intervention strategies to reduce the risks associated with drug use.

When we consider the social problem of problematic drug use, we enter a challenging space. Like many social problems, opinions are often extreme and heartfelt. In the 2020 optional-reading article, Don’t Forget the Other Pandemic Killing Thousands of Americans, author Kate Briquelet writes, “Amid social distancing, authorities nationwide are reporting a surge in fatal opioid overdoses. Addiction and recovery advocates say the US is now battling two epidemics at once. From 1999 to 2018, opioid overdoses involving prescription and illicit drugs have killed nearly 450,000 Americans.” We have not just one pandemic but two.

The COVID-19 pandemic has enabled us to see how social environments and conditions impact the consequences of drug use and addiction. For example, many experts are worried about the negative impacts of social isolation on those with substance use disorders. Isolation might increase depression, and the related self-medication will employ illegal substances. In addition, individuals who use opioids alone and overdose would have no one there to call 911 or administer Narcan, the overdose reversal medication. Beyond the individualized psychological view of drug use, a sociological perspective reveals the social conditions that can cause substance use, as well as make the consequences worse for certain structurally vulnerable groups.

Social scientists assert that people often seek to alter their consciousness deliberately. Sometimes, they choose prayer or meditation. Sometimes, they choose to dance or sing in a choir. Sometimes, they choose a pound of chocolate or a runner’s high. Sometimes, they choose alcohol, cannabis, or other mind-altering substances. Many find this altered state without it becoming either a personal or a social problem.

As we look at the social problem of problematic drug use worsened by COVID-19, the following questions guide our curiosity:

- How can we describe drug use and misuse as a social problem?

- How does social location impact the experience of harmful drug use?

- How do the five models of addiction differ in how they explain the causes and consequences of harmful drug use?

- Which interdependent actions increase social justice related to problematic drug use?

The Social Problem of Drug Use and Misuse

There are many ways to construct drug use and addiction as a social problem. Addiction is a chronic, relapsing disorder characterized by compulsive drug seeking and use despite adverse consequences (National Institute on Drug Abuse 2020). But it’s not just the antisocial problem of drug use that is the social problem equal impact of drug use on families and communities the social prodrug users chapter will not discuss drug use as inherently bad. The opioid epidemic impacts everyone, from individuals to families, hospitals, workplaces, and governments. It goes beyond the experience of one individual.

Secondly, in our exploration of drug use and misuse, we see social construction at work. You may notice that throughout this chapter, we use the word cannabis to describe the drug that is commonly known as marijuana or weed. The common word for marijuana is racist. It reflects a racist past. More specifically, the United States experienced an increase in Mexican immigration after the 1910 Mexican War of Independence. Some immigrants used the herb marijuana for casual smoking. Although the immigrants were important in providing needed agricultural labor, the increase in immigration raised xenophobic fears.

Mexican immigrants were often blamed for property crimes and sexual misconduct. White people in power conveniently blamed the use of marijuana for this. “One Texas state legislator pro-claimed on the senate floor: “All Mexicans are crazy and this stuff [cannabis] is what makes them crazy” (Ghelani 2020). In 1937, Harry Ainsliger, head of the Federal Bureau of Narcotics testified before Congress saying, “marihuana is an addictive drug which produces insanity, criminality, and death” (Ghelani 2020). Associating the use of cannabis with Mexican immigrants by manpower marijuana was a way to assert power and control over a particular ethnic group. This is using language as a social construction. To resist this oppression, we will use the word cannabis instead of the word marijuana in this chapter, except when we are quoting from other people. In addition, we remember that a social problem arises when groups of people experience inequality. This point is particularly important when we discuss drug use and harmful drug use. People of all races use drugs at the same rate. However, People of Color are likely to be arrested and jailed for drug offenses. White people are more likely to be seen as needing medical intervention, and therefore they are more likely to receive treatment. More specifically:

Although Black Americans are no more likely than Whites to use illicit drugs, they are 6–10 times more likely to be incarcerated for drug offenses. (Netherland and Hansen 2017)

This racialized response to harmful drug use is a deep source of inequality, a key component of a social problem. Finally, we recall that social problems must be addressed interdependently, using both individual agency and collective action. In this case, citizens, lawmakers, health care workers, community advocates, and the individuals themselves must act to address the social problem. We’ll look at various solutions in more detail in Recovery is Social Justice.

Drug Use

Drug use can be a problem for anyone, but it is people’s different social locations that determine how harmful the drug use will be for themselves and for their family, friends, and community. Harmful drug use occurs when it negatively impacts a person’s health, livelihood, family, freedom, or other important aspects of their life.

One of the dominant approaches to understanding addiction involves looking solely at how a person’s brain is affected by drug use. Another popular approach focuses on the psychology of the user and the chemical traits of the substance. Both approaches ignore social issues such as poverty, racism, and sexism that increase the harmfulness of drug use for certain individuals, populations, and neighborhoods. Incarceration, disease (such as HIV), other negative health impacts, job loss, and family disruption are examples of harms associated with drug use that are more or less likely to occur depending on one’s social location.

Problematic Drug Use

Social scientists point out that a person’s socioeconomic class may impact whether they can continue to work or go to school while using substances (Zinberg 1984; Singer and Page 2014; Friedman 2002). For example, White middle-class users of opioids, like heroin, are less likely to get arrested or go to jail. Therefore, they can more often keep their jobs and still earn money.

Racism in our society creates differences in how White people and People of Color are treated when they use drugs. White people are more likely to be seen as people experiencing a medical condition. Therefore, they need drug treatment to recover. Black, Brown, and Indigenous people are more likely to be seen as criminals. They are more likely to be arrested and put in jail than receive treatment This chapter will discuss how racist social structures shape the experiences of problematic drug use.

A problem in deciding how to think about and deal with drugs is the distinction between legal drugs and illegal drugs. It makes sense to assume that illegal drugs should be the ones that are the most dangerous and cause the most physical and social harm, but research shows this is not the case.

Rather, alcohol and tobacco cause the most harm even though they are legal. As Kleiman and his research team note about alcohol: When we read that one in twelve adults suffers from a substance abuse disorder or that 8 million children are living with an addicted parent, it is important to remember that alcohol abuse drives those numbers to a much greater extent than does dependence on illegal drugs. (2011). According to the CDC, cigarette smoking kills 480,000 people due to complications from smoking or secondhand smoke (CDC 2022). Alcohol use prematurely kills 140,000 people per year in the US. These deaths are caused by physical damage related to long-term use. They are also caused by drinking too much alcohol in a short period of time. DUI fatalities are one example of this premature death. The rate of premature death is much higher for legal drugs than illegal ones.

Dependence

Substances that we consider drugs interact with our bodies in different ways. Drugs are often grouped by the kinds of physical effects they have. Some drugs, called depressants, slow down the central nervous system. Hallucinogens cause people to hallucinate, to see, hear, or experience things that are not physically real. Narcotics, derived from natural or synthetic ingredients, are effective at relieving pain, but they depress the nervous system. They are also highly physically addictive. Stimulants speed up the nervous system, potentially causing alertness, euphoria, or anxiety. Finally, cannabis may create euphoria, hunger, and relaxation and dull the sense of time and space.

Important distinctions exist between addiction, physical dependence, and drug use. These three are not mutually exclusive, but they differ from each other in significant ways. Addiction is often associated with a mental health diagnosis such as substance use disorder. Rather than using the diagnosis of addiction, health professionals now use the language of substance use disorder (SUD), which is a condition in which there is uncontrolled use of a substance despite harmful consequences. People with SUD have an intense focus on using a certain substance(s), such as alcohol, tobacco, or illicit drugs, to the point where the person’s ability to function in day-to-day life becomes impaired (Saxon 2023). Physical dependence means that the body has built up a tolerance to the drug and that one must take the substance to not feel ill. Drug use is just the intake of a substance that produces a change in your body. This can happen with or without addiction or physical dependence.

Harmful Drug Use: Exploring Unequal Outcomes

By 1994, the deindustrialization of the US economy produced by global economic shifts, was having a deleterious impact on working-class Black communities. The massive loss of jobs in the manufacturing sector, especially in cities like Detroit, Philadelphia, Chicago, New York, and Los Angeles, had the result, according to Joe Willam Trotter, that “the black urban working class nearly disappeared by the early 1990s.” Combined with the disestablishment of welfare state benefits, these economic shifts caused vast numbers of black people to seek other—sometimes “illegal”—means of survival. It is not accidental that the full force of the crack epidemic was felt during the early 1980s and 1990s (Davis 2021).

The massive expenditures on the curtailment of the drug epidemic also shifted our views on drug use. The United States became much more punitive towards drugs. The courts treated harmful drug use as a criminal justice issue rather than as a substance dependence issue. The War on Drugs created tougher sanctions on drug use in America. The Drug Enforcement Agency was created in 1973 to provide another arm of the government to tackle the specific issue of drugs. By the 1980s, lengthy sentences for drug possession were also in place. One to five-year sentences for possession were increased to more than 25 years.

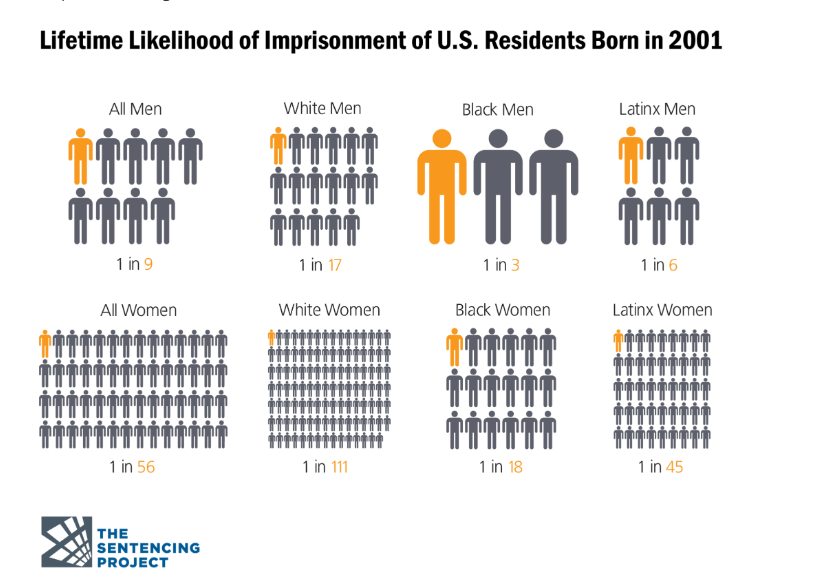

The War on Drugs and its associated policies also drove massive increases in prison populations. Between 1980 and 2010, the US prison population quintupled. The population only began to decline slightly in the early 2010s. As of 2019, the United States still imprisoned more than 2 million people in prisons and jails. Mass incarceration refers to the overwhelming size and scale of the US prison population. The United States has the largest prison population in the world, but how did this come to be the case?

The War on Drugs is one of the major drivers of the prison population in the United States. In 1971, President Richard Nixon declared a War on Drugs, dedicating increased federal funding and resources to quelling the supply of drugs in the United States. This war continued to ramp up through the 1980s and 1990s, especially as crack cocaine became a growing concern in the media and public sphere. Crack cocaine was publicly portrayed as a highly addictive drug sweeping its way through America, allowing politicians to capitalize on this hysteria and pass policies that rapidly increased the prison population. Even so, the vast majority of arrests and enforcement were not of high-level, violent dealers. More often, police arrested small-time dealers or people struggling with addiction. In fact, during the 1990s, the period of the largest increase in the US prison population, the vast majority of prison growth came from cannabis arrests (King and Mauer 2006).

The 1980s and 1990s were also an era where states turned to partnerships with private companies to meet the booming demand for facilities, leading to the rise of private prisons. Private prisons are for-profit incarceration facilities run by private companies that contract with local, state, and federal private prisons. The business model of private prisons incentivizes them to keep their prisons as full as possible while spending as little as private prisons care for inmates. Down 16 percent from its peak in 2012, private prisons still held 8 percent of all people incarcerated at the state and federal level as of 2019 (The Sentencing Project 2022). This general statistic hides state-to-state differences, though. For instance, Oregon has private prison facilities in the state, while Texas has the highest number of people incarcerated in private prisons.

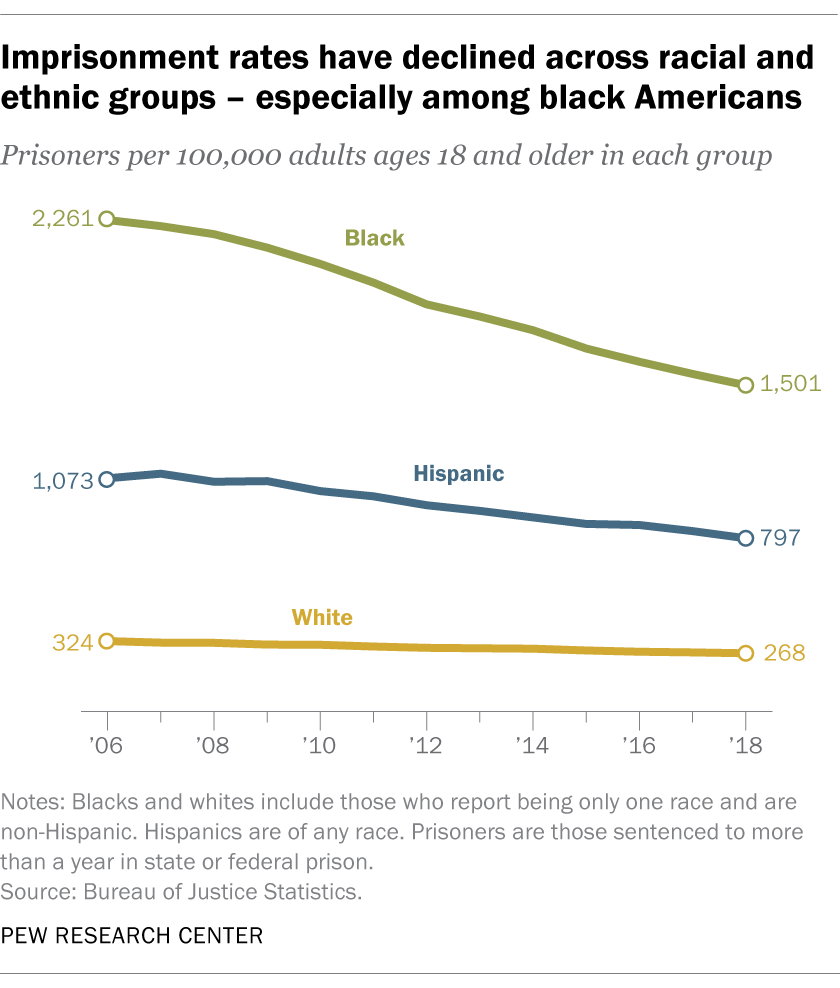

Even as the racial gap in incarceration has narrowed in recent years, the US disproportionately incarcerates Black Americans. While Black Americans make up 12 percent of the population, they make up over 33 percent of incarcerated individuals (Gramlich 2019). Similar trends exist among Latino Americans: while Latinos comprise 16% of the US population, they account for 23% of incarcerated individuals (Gramlich 2019). In contrast, while White Americans comprise 63% of the population, they only make up 30% of those incarcerated (Gramlich 2019).

This network of policies and unequal institutional practices led to what scholar Michelle Alexander terms The New Jim Crow. The New Jim Crow refers to the network of laws and practices that disproportionately funnel Black Americans into the criminal justice system, stripping them of their constitutional rights as a punishment for their offenses in the same way that Jim Crow laws did in previous eras. Because of these new mass incarceration policies, a new iteration of the racial caste system has emerged: one where Black Americans can legally be denied public benefits, housing, the right to vote, and participation on juries because of a criminal conviction.

Nearly three-quarters of the people in federal prison are nonviolent offenders with no history of violence. Black men are disproportionately arrested and imprisoned. These statements are all true, but what do they actually mean? Sociologists look at patterns of difference or change over time to measure inequality between groups and to explain it. Social problems sociologists often explore the efficacy of possible interventions. Because we want to take effective action, we must examine the information we use to make decisions very carefully.

We see deep inequalities in our criminal justice system. However, we also see competing claims about what is true. How, for example, can the first two statements be true at the same time? The issue lies in combining two populations in the first statement—people who commit violent crimes and people who have a prior criminal record. Getting a prior criminal record might include being arrested for being at a protest, even if you weren’t convicted. It could include failure to pay child support. It could also include having a few grams of cannabis in Oregon prior to 2015 when the related law changed. Many people have a criminal record, but they are not actually dangerous to society.

When you examine the second statement, it only includes one group of people: people who are in prison for non-violent offenses. Many of these offenses are related to drug possession, and some of them are related to drug distribution. Although harmful drug use causes harm, these offenses are non-violent. By looking at the numbers in this way, we open the door to considering options for social justice that are effective rather than carceral.

Harmful Drug Use: Exploring Unequal Outcomes

Disproportionality is the overrepresentation or underrepresentation of a racial or ethnic group compared with its percentage in the total population. We can see disproportionality across group disproportionality locations. Racial disproportionality is commonly related to harmful drug use and the criminal justice system. White people make up 60% of the overall population of the United States, but they make up only 38% of people who are incarcerated. Black people make up 13% of the overall population of the United States, but they are also 38% of the incarcerated population. Hispanic people are 18% of the total population and 21% of people in prison or jail. Finally, Native Americans have disproportionality, and 2% of those in jail. In every case, we see disproportionality.

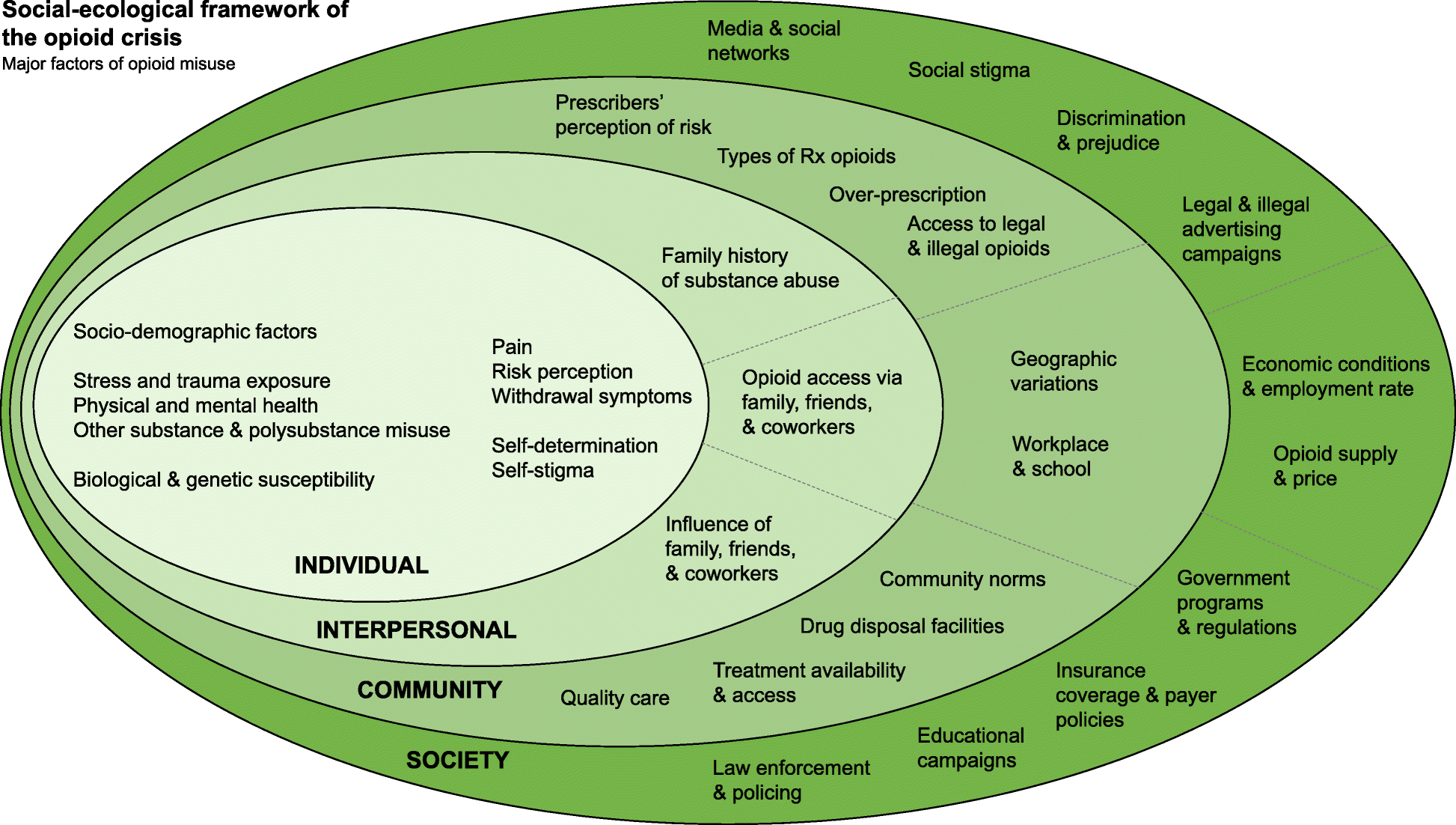

However, the measure of disproportionality doesn’t tell us why the difference exists or what to do about it. If you consider the infographic The Social Ecological Framework of the Opioid Crisis, you see many causes of inequality. The causes of disproportionality are often disparity. Disparity is the unequal outcomes of one racial or ethnic group compared with outcomes for another racial or ethnic group (Child Welfare Information Gateway 2021). Disparity can be used to compare any groups with different social locations.

However, as we consider the War on Drugs as an example, we see that systems, laws, policies, and practices privilege White people over People of Color. In one example, the sentencing for crack cocaine and powder cocaine are significantly different. Distributing 5 grams of crack cocaine has a 5-year mandatory minimum federal prison sentence. Distributing 500 grams of powder cocaine has the same sentence. More than 80% of the crack cocaine defendants in 2002 were Black, even though two-thirds of the crack cocaine users were White or Hispanic (The Sentencing Project 2004). Powder cocaine is more likely to be used by wealthier people, who are disproportionately White (Vagins and McCurdy 2006).

Even when judges have more discretion in what sentences they impose, racial disparities exist: Racialized assumptions by key justice system decision-makers unfairly influence outcomes for people who encounter the system. In research on presentence reports, for example, scholars have found that People of Color are frequently given harsher sanctions because they are perceived as imposing a greater threat to public safety and are therefore deserving of greater social control and punishment. (Nellis 2021).

These biases are both conscious and unconscious, and they occur at every level of the criminal justice system, from police to lawyers, to judges, to the politicians who make the laws in the first place. Structural racism and individual racist ideas result in racial disparity in the criminal justice system.

The Opioid Crisis: Medical Intervention, not Crime

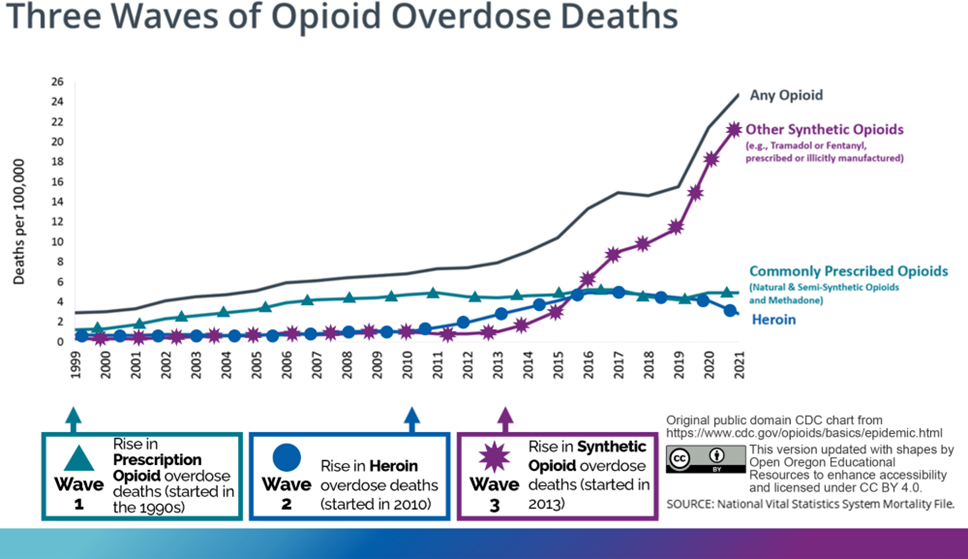

Another way to notice racism at work in response to harmful drug use is to examine the opioid crisis. The opioid crisis refers to the surge in fatal overdoses linked to opioid use (DeWeerdt 2019). The overdose fatality rate rose by 345% between 2001 and 2016 (Jalali et al. 2020). Opioids are a class of drugs that cause euphoria. Opioids include heroin, morphine, codeine, hydrocodone, OxyContin®, and fentanyl (Johns Hopkins Medicine 2023). Heroin is an illegal drug. The others are prescription drugs that doctors prescribe for pain relief.

Nearly 75% of drug overdoses in 2020 involved a legal or illegal opioid (Centers for Disease Control 2022). The CDC describes the crisis using three waves. The first wave started in the 1990s. In this wave, the deaths were primarily due to overdoses on prescription opioids, like OxyContin® and Vicodin®. This wave was a result of the over-prescription of opioid-based painkillers, causing some individuals to become physically dependent. The second wave started in 2010.

The second wave was due to overdoses related to using heroin. This use of heroin partially resulted from a decrease in the amount of legally available prescription painkillers. The third wave started in 2013. This wave marked an increase in overdose deaths from synthetic opioids like fentanyl and tramadol. While fentanyl can be prescribed, this wave was driven by illegally manufactured substances.

The response to heroin use and misuse was carceral. Race was at the core of drug policy that emerged from an increase in heroin use in urban centers in the 1960s. According to media accounts, the face of the heroin user at that time was “black, destitute and engaged in repetitive petty crimes to feed his or her habit” (Hart and Hart 2019:7). A popular solution to this racialized drug scare was to incarcerate Black users of heroin and offer methadone treatment to White users.

New York state was a forerunner in creating harsh drug laws to address heroin use in cities. The infamous Rockefeller drug laws of 1973 created mandatory minimum prison sentences of 15 years to life for possession of small amounts of heroin and other drugs (Hart and Hart 2019). 90% of those convicted under the Rockefeller drug laws were Black and Latinx, though they represent a smaller proportion of people who use drugs in the population (Drucker 2002).

The societal response to opioid use and dependence among White people during this crisis has been gentler, relying more on treatment than the criminal justice system (Hart and Hart 2019; James & Jordan 2018). According to statistics from the Bureau of Justice, 80% of arrests for heroin trafficking are among Black and Latinx people, even though White people use heroin at higher rates and are known to purchase drugs within their own racial community (James & Jordan 2018).

As we examine the response to the over prescription of opioids and the harmful use of fentanyl, we see a stark difference in public response. We see a focus on monitoring doctors so that they don’t overprescribe opioids. We see a focus on the overuse of opioids as a medical disease needing treatment rather than criminalizing the user of the drug. Our response to drug overuse in the opioid crisis is racialized. Researchers Netherland and Hansen summarize the unequal response this way:

The public response to White opioids looked markedly different from the response to illicit drug use in inner-city Black and Brown neighborhoods, with policy differentials analogous to the gap between legal penalties for crack as opposed to powder cocaine. This less examined ‘White drug war’ has carved out a less punitive, clinical realm for Whites where their drug use is decriminalized, treated primarily as a biomedical disease, and where White social privilege is pre- served… in the case of opioids, addiction treatment itself is being selectively pharmaceutical in ways that preserve a protected space for White opioid users, while leaving intact a punitive, carceral system as the appropriate response for Black and Brown drug use. (Netherland and Hansen 2017)

We can see a racialized response in the differential access to treatment options for the harmful use of opioids White people who use opioids have been given more access to the preferred addiction treatment medication, buprenorphine. Treatment with buprenorphine is less stigmatized because it is dispensed like any other pharmaceutical medication at a private doctor’s office. Another treatment option is methadone. This method requires frequent visits to a methadone clinic. Often BIPOC receive treatment at the less- preferred methadone clinics (Hansen 2015). Politicians legalized Buprenorphine treatments for opioid use disorder, supporting the privileged lives of middle-class White addicts (Netherland & Hansen, 2017).

These characteristics of the social landscape contribute to increased health harms, such as contracting HIV or hepatitis C, for Black people who use drugs. Health harms caused by substance use are higher among Black people who use drugs, not because they participate in riskier drug use behavior, but because they reside in under-resourced communities that hinder access to health-promoting services and materials (Cooper et al. 2011). Accordingly, opioid overdose rates for Black people have historically been higher than those for White people in some states. Recently this rate has been increasing more rapidly, though the media attention surrounding the opioid crisis mostly focuses on drug use by White people (James & Jordan 2018). We also see differences in the harm caused by harmful drug use because of the lack of treatment centers in rural areas. The lack of treatment centers harms White people who live in these areas and People of Color.

Five Models of Addiction

In this section, we explain the five models of addiction that are dominant in US society: the moral view, the disease model, a public health perspective, a sociological approach, and an intersectional approach. We will discuss these five views or models, as well as where this society can be found in action within society.

Moral View

The moral view depicts the use of illicit substances and the state of addiction as wrong or bad. Illicit drug use is understood as a sin or personal failing. Faith-based drug rehabilitation programs are one location where we see the moral model in use. Through qualitative interviews with individuals who had attended such a facility, Gowan and Atmore (2012) found that within the teachings of evangelical conversion-based rehab, substance use is thought to be rooted in immorality. This requires the user to convert and submit to religious authority to recover. Gowan and Atmore (2012) found that addiction implied that the root of addiction was in secular or nonreligious life. The rigid structure of faith-based drug treatment programs can be helpful for some people in recovery. Some people also find that faith-based community programs like twelve step programs are effective.

| Schedule | Definition | Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Schedule I | No currently accepted medical use and a high potential for abuse. | Heroin, LSD, and cannabis |

| Schedule II | High potential for abuse, with use potentially leading to severe psychological or physical dependence. These drugs are also considered dangerous. | Vicodin, cocaine, methamphetamine, etc. |

| Schedule III | Moderate to low potential for physical and psychological dependence. Abuse potential is less than Schedule I and Schedule II drugs but more than Schedule IV. | Tylenol with codeine, ketamine, etc. |

| Schedule IV | Low potential for abuse and low risk of dependence. | Xanax, Soma, Valium, etc. |

| Schedule V | Lower potential for abuse than Schedule IV and consist of preparations containing limited quantities of certain narcotics. | Robitussin AC with codeine, Lomotil, etc. |

The moral view toward drug use can also be seen in our criminal justice system and the criminalization of drug use. Criminalization is the act of making something illegal (Definition of Criminalize 2023). The 1970 Comprehensive Drug Abuse and Control Act (US House 1970) created drug categorizations, called schedules, based on the drug’s potential for abuse and dependency and its accepted medical use. This new system of categorization acknowledged the medical use criminalization while heightening the criminalization of other drugs. Drug policy in the United States is guided by the moral view of drug use. It calls for those who use substances to be punished, whether it is through fines, some form of home arrest, or incarceration.

Disease Model

Understanding drug use and particularly addiction to mind-altering substances as a disease is another dominant model found within US society and its social institutions. The idea of considering substance use a disease is at least 200 years old. Researching the history of the disease concept of addiction, sociologist Harry Levine (1978) found that habitual drinking during the eighteenth century was not considered a problematic behavior. The emergence of the temperance movement in the nineteenth century shifted American thought toward understanding addiction as a progressive disease. In this idea of disease, a person loses their will to control the consumption of a substance. In the 1940s, the National Council of Alcoholism was founded by E.M. Jellinek, a professor of applied physiology at Yale. The purpose of this council was to popularize the disease model of addiction by putting it on scientific footing by conducting research studies on drug use. Science promoted the disease model. It did not create it (Reinarman 2005).

The disease model of addiction also involves the use of pharmaceuticals, such as methadone, to treat physical and psychological dependence on opiates. Physicians Vincent Dole and Marie Nyswander successfully researched the use of methadone to stabilize a group of 22 patients previously addicted to heroin. Dole and Nyswander (1965) found that with the medication and a comprehensive program of rehabilitation, the patients showed marked improvements. They returned to school, obtained jobs, and reconnected with their families. The researchers found that the medication produced no euphoria or sedation and removed opiate withdrawal symptoms.

The legitimacy of the disease model of addiction was reinforced by the clinical research findings of Dole and Nyswander, which showed that a pharmaceutical (i.e., methadone) could be used to treat addiction. Dole and Nyswander (1965) wrote: “Maintenance of patients with methadone is no more difficult than maintaining diabetics with oral hypoglycemic agents, and in both cases, the patient should be able to live a normal life.” Those who support the disease model of addiction often compare addiction to diabetes. The analogy demonstrates the similarity of addiction to other diseases.

Since the 1990s, addiction has been understood as a neurobiological disease and referred to as a chronic relapsing brain disease or disorder. Using brain imaging technology, scientists and researchers came to find that addictive long-term use of substances changed the structure and function of the brain and had long-lasting neurological and biological effects. Social scientists have questioned the sole use of the disease model to understand addiction, asserting that addiction also involves a social component. They point out that the disease of addiction is not diagnosed through brain scans. Rather, it is often identified when one is breaking cultural and social norms around productivity and compulsion (Kaye 2012).

Public Health Perspective

A public health perspective toward substance use incorporates a sociological understanding of drug use but focuses on maintaining the health of people who use drugs. Often this approach is labeled harm reduction. Harm reduction is a set of strategies and ideas aimed at reducing negative consequences associated with drug use (Harm Reduction Principles N.d.). Harm reduction is also a practical movement for social justice built on a belief in, and respect for, the rights of people who use drugs. It focuses on providing people who use drugs with the information and material tools to reduce their risks while using drugs. This perspective focuses on reducing the harm of substance use rather than requiring harm reduction all drug use. Similar harm reduction strategies are wearing seat belts or providing adolescents with condoms.

One of the most well-known harm reduction practices is syringe exchange. This became legal during the HIV epidemic of the 1980s and ’90s to help people who inject drugs avoid infection with the then-deadly virus. Currently, harm reduction is also associated with the distribution of the opioid overdose reversal antidote—Narcan or Naloxone. This harmless medication can almost instantaneously reverse an opioid overdose, saving a person’s life. The public health or harm-reduction perspective toward drug use can be controversial because some believe that it enables drug use. There is no scientific evidence to support this idea. Instead, scientific evidence shows that syringe exchange reduces HIV and hepatitis C rates, and the distribution of Narcan lowers drug overdose mortality rates (Platt et al. 2018; Fernandes et al. 2017; Chimbar & Moleta 2018).

Sociological Model

The sociological model of drug use and addiction examines how social structures, institutions, and phenomena may lead individuals to use mind-altering substances to cope with difficulty and distress. A sociological view also examines how social inequalities can make the impacts of drug use worse for some social groups than others. Within the sociological model, a socio-pharmacological approach looks at how social, economic, and health policy might exacerbate harm to people using substances. Socio pharmacology is a sociological theory of drug use developed by long-time drug use researcher Samuel R. Friedman. Friedman (2002) writes that approaches toward understanding drug use that focus on the psychological traits of the people using the drugs and the chemical traits of the drugs ignore socioeconomic and other social issues that make individuals, neighborhoods, and population groups vulnerable to harmful drug use.

To consider how the socio-pharmacological approach plays out in everyday life, consider how drug policy prohibits the use of heroin and results in several harmful effects. New syringes can be hard to find. People will inject in unclean and rushed circumstances, which may negatively impact their health by putting them at risk of contracting HIV or life-threatening bacterial infections. This type of analysis is also thought of using the analytic concept of risk environments developed by Tim Rhodes. A risk environment is a social or physical space where a variety of things interact to increase the chances of a drug-related risk environment. An analysis of the risk environment looks at how the relationship between the individual and the environment impacts the production or reduction of drug harm.

In his socio-pharmacology theory, Friedman also notes that the social order might cause misery for some social groups, which might cause people to self-medicate with drugs. People who experience class, gender, or racial oppression suffer harm. As a way to deal with that harm, they may choose to self-medicate with drugs or alcohol. For example, working a low-paying service job where you deal with unhappy customers and mis- treatment from your boss may lead you to blow off steam by using substances. Individualistic theories of drug use stigmatize and demonize individuals who use drugs as being weak or criminal. According to the socio-pharmacological approach, if anything should be demonized, it should be the social order—not the individual who uses drugs (Friedman 2002).

Looking at the social determinants of the opioid crisis provides a way to discuss a sociological approach to studying drug use. opioid crises to understand the opioid crisis focus on the supply of opioids in the US and whether they were pharmaceutical or illicit. This approach misunderstands the reasons individuals use opioids. The label deaths of despair has been used to describe three types of mortality that are on the rise in the US. Deaths of despair have caused a decline in the average lifespan among Americans. These three deaths occur from drug overdose, alcohol-related disease, and suicide. Death from these conditions has risen sharply since 1999, especially among middle-aged White people without a college degree (Dasgupta, Beletsky, and Ciccarone 2018).

Researchers are examining how economic opportunities impact opioid use and overdose rates. In a study focused on the Midwest, Appalachia, and New England, areas that are predominantly White, researchers found that mortality rates from deaths of despair increased as county economic distress worsened. In rural counties with higher overdose rates, economic struggle was found to be more associated with overdose than opioid supply (Monnat 2019). Analysis of the social and economic determinants of the opioid crisis notes that the jobs available in poor communities, which are often in manufacturing or service, present physical hazards and cause long-term wear and tear on the worker’s body (Dasgupta et al. 2018). An on-the-job injury can lead to chronic pain, which may disable a person. The disability may cause them to seek pain relief through opioids. The resulting addiction pushes them into poverty and despair.

A 2017 report from the National Academy of Sciences used a sociological view of drug use when it commented on the cause of the opioid crisis. The report states: Overprescribing was not the sole cause of the problem. While increased opioid pre- scribing for chronic pain has been a vector of the opioid epidemic, researchers agree that such structural factors as lack of economic opportunities, poor working conditions, and eroded social capital in depressed communities, accompanied by hopelessness and despair, are root causes of the misuse of opioids and other substances. (Zoorob and Salemi 2017)

However, this research into deaths of despair focused on the increased opioid-related deaths due to overprescription in the first wave of the opioid crisis. Although the researchers don’t name it specifically, they were looking at patterns of drug use and abuse by White people. The researchers demonstrate implicit bias. As the crisis continues, researchers are examining of the second and third waves of the crisis. According to a study from Marjorie C. Gondré-Lewis, Tomilowo Abijo, and Timothy A. Gondré-Lewis: Categorically, from 2015 to 2017, African Americans experienced the highest OOD increase of all races analyzed; 103% for opiates and 361% for synthetic opioids in large central metropolitan cities, and respectively 100% and 332% in large fringe metros Illicitly manufactured fentanyl accounts for increased overdose deaths more than any other opioid across the USA. (2022)

The opioid crisis is now impacting urban, Black people disproportionately. Despite the research biases we notice here, a sociological view of drug use helps us to understand the social contexts that can lead to drug use and cause it to be harmful or deadly. Without a sociological analysis, we’d only be looking at individual people and drugs. We would miss the entire social environment which influences both drug use and the consequences of drug use. A sociological analysis notices widespread social structural elements that might increase drug use: racism, economic despair, and hopelessness. This analysis can help us create policies and programs that can be beneficial for large numbers of people. From the sociological perspective, we see that, like other social problems, differences in social location create unequal outcomes.

Intersectional Model: Colonization and Drug Use

Indigenous people report the second highest rate of illicit drug use disorder between 2015 and 2019, at 4.8%. The highest percentage is among people who identify as two or more races or ethnicities. Indigenous people are also the highest percentage of people who sought treatment for illicit drug use disorders and received it (Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality 2021).

The work of researcher and professor Maria Yellow Horse Brave Heart, explains how the historically-based trauma experienced by Indigenous communities in the United States may impact substance use. She emphasizes that the traumatic losses suffered across generations by the North American Indigenous populations meet the definition of genocide. She lists massive traumatic group experience trauma as part of the intergenerational trauma experienced by this community, which may contribute to substance use (2003).

This list includes traumas such as massacres; prisoner of war experiences; starvation; displacement; separation of children from families and placement in compulsory and often abusive boarding schools; disease epidemics; forced assimilation; and the loss of language, culture, and spirituality. All of this contributes to the breakdown of family kinship networks.

Brave Heart points to an 1881 US policy outlawing the practice of Native ceremonies, which prohibited traditional mourning practices. This undermined practices of healing and resolution that might improve wellness and potentially lower problematic substance use levels. Urban Indigenous people who use alcohol and/or other illicit substances reported symptoms of historical trauma (Wiechelt et al. 2012). Brave Heart (2003) points out that alcohol was not part of Indigenous culture except for specific ceremonies before colonial contact.

Researchers suggest that treatments for substance use disorder among Indigenous peoples should coincide with decolonizing practices. This means that Indigenous communities should be supported in making attempts and achieve control of land and services. Nutton and Fast report that:

…communities that have made attempts to regain control of land and services have been found to have lower suicide rates, reduced reliance on social assistance, reduced unemployment, the emergence of diverse and viable economic enterprises on reservation lands, more effective management of social services and programs, including language and cultural components, and improved management of natural resources. (2015).

Identity formation can also be a helpful part of drug treatment for Indigenous individuals. Research indicates that increased participation of Indigenous peoples in their culture of origin can decrease the prevalence of substance use disorder. (Nutton & Fast 2015). Finally, all drug treatment interventions should be culturally adapted for Indigenous communities. For example, among Indigenous people inhabiting the Great Plains, the Sun Dance was performed in thanksgiving for a bountiful year and a request for another year of food, health, and success. Today community members pledge to do the Sun Dance to maintain their sobriety from alcohol or drugs.

Recovery is Social Justice

Though the continued opioid (and now fentanyl) crisis may be a reason to despair, there are many individuals, social movements, and other organizations who are working to address problems associated with substance use. Social science, public health, biomedical, and legal scholars and researchers are diligently producing more evidence-based knowledge to guide societal efforts toward more humane and pragmatic responses to substance use. Reducing harmful drug use is social justice.

Harm-Reduction Movement

Harm reduction offers a lens through which we can understand and address issues associated with substance use. Harm reduction can be understood as a set of practices. It can also be understood as a social justice movement. The philosophy behind harm reduction revolutionizes the way we respond to human problems, namely addiction, drug overdose, and HIV. Harm reduction uses a grassroots approach based on advocacy from and for people who use drugs and accept alternatives to abstinence that reduce harm (Marlatt 1996). According to the Harm Reduction Coalition, the central harm reduction organization in the US, a core principle of harm reduction philosophy “accepts for better or worse, that licit and illicit drug use is part of our world and chooses to work to minimize its harmful effects rather than simply ignore or condemn them.”

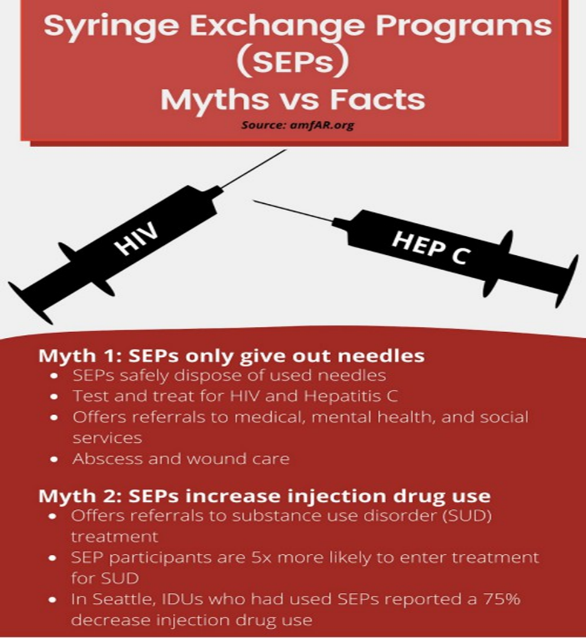

Syringe exchange programs, or their more current name—syringe service programs—were one of the early harm reduction efforts made to address the AIDS crisis of the 1980s and ’90s. The Harm Reduction Coalition states that “Syringe service programs (SSPs) distribute sterile syringes, safer drug use supplies, and education to people who inject drugs.” The current opioid crisis in the United States is causing a dramatic increase in infectious diseases associated with injection drug use, such as HIV or hepatitis C. Syringe service programs are known to reduce HIV and hepatitis C infection rates by an estimated 50% (Platt et al. 2017). When paired with medication-assisted treatment to treat opioid dependence, syringe service programs can reduce HIV and hepatitis C transmission by over two-thirds (Platt et al. 2017; Fernandes et al. 2017). Sometimes people oppose syringe service programs because they think it might enable drug use.

Research shows the opposite. According to the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2019), new users of syringe service programs are “five times more likely to enter drug treatment and three times more likely to stop using drugs than those who don’t use the programs.” Syringe service programs can also prevent opioid overdoses by educating people who use drugs about ways to prevent overdose. Syringe service programs provide training on how to recognize an overdose and how to use naloxone or Narcan, a harmless medication that reverses opioid overdoses. Often syringe service programs will distribute overdose prevention kits that include naloxone (CDC 2019).

Decriminalize Low-Level Drug Offenses

National social justice advocates recommend decriminalizing low-level drug offenses as a way to decrease oppression in our criminal justice system. Decriminalization is the act of reducing penalties for possession/use of small amounts from criminal sanctions to fines or civil penalties (Galvin 2014). For example, in order to address the racial and ethnic disparities in criminal justice systems, Ashley Nellis from the Sentencing Project recommends that we: discontinue arrest and prosecutions for low-level drug offenses which often lead to the accumulation of prior convictions which accumulate disproportionately in communities of color. These convictions generally drive further and deeper involvement in the criminal legal system. (Nellis 2021)

Decreasing criminal involvement in the first place related to harmful drug use is a step in treating harmful drug use like a medical condition that needs treatment rather than a criminal condition that needs punishment.

Legalization of Cannabis

Social movements, as well as individuals who sought to decriminalize and legalize cannabis, were often motivated by the United States’s long history of systemic racism and the war on drugs. Legalization means to make the possession and use of a drug legal (Galvin 2014a). Since 2012, 24 states and Washington, D.C., have legalized cannabis for adults over the age of 21. Legalizing cannabis has meant fewer arrests and jail time. In Oregon, the number of cannabis arrests decreased by 96 percent from 2013–2016, the year cannabis was legalized for adult recreational use Drug Policy Alliance 2022).

The Drug Policy Alliance, a nonprofit organization that advocates for the decriminalization of drugs, examined rates of youth cannabis use. They found that since the legalization of cannabis use in some states, youth use rates have remained stable and, in some cases, legalization has also found that legalization has not made roadways less safe due to driving under the influence of cannabis. Finally, they show that states are using the money generated through taxes on legal cannabis for social good (The Drug Policy Alliance 2022). In Oregon, 40% of the cannabis tax revenue goes to the state school fund, and 20% goes to alcohol and drug treatment.

However, health researchers remain concerned about the impacts of cannabis legalization on adolescent cannabis use. Increasing amounts of research reveal correlations between adolescent cannabis use and short and potentially long-term impairments on cognition, worse academic/vocational outcomes, and increased prevalence of psychotic, mood, and addictive disorders (Hammond et al. 2020). Though cannabis use rates among adolescents are higher in states that have legalized the substance, those rates were higher even before legalization (Choo et al. 2014; Wall et al. 2011; Ammerman et al. 2015). Legalization itself did not cause higher usage rates.

Other negative impacts of cannabis use have risen in states where cannabis is legalized. Motor vehicle accidents and deaths where cannabis was involved have increased. Young children and pets accidentally overdose more often. Finally, emergency rooms see more patients and hospitalize them more often due to potent cannabis causing psychosis, depression, and anxiety (Committee on Substance Abuse & Committee on Substance Abuse Committee 2015, as cited in Hammond et al. 2020).

When considering whether cannabis should be legal, Hammond et al. (2020) point out that we must balance the negative impacts (discussed above) with the positive effect of decriminalization, reducing youth juvenile justice involvement. Youth involvement in the juvenile justice system can have long-lasting negative impacts on the life outcomes of youth. For example, involvement in the juvenile justice system may disrupt education or cause long-lasting mental health problems. We must consider the reduction of these types of issues alongside the known negative impacts of youth cannabis use. Another equity issue arises with the legalization of cannabis and the rise of a money-making industry. A drug-related felony on an individual’s record may be a barrier to gaining a license to sell cannabis through a dispensary. As we’ve discussed in this chapter, due to systemic racism within drug policy enforcement, those with drug-related felonies on their record are disproportionately Black. This means that Black entrepreneurs may be disproportionately blocked from entering the cannabis industry. Several cities have implemented equity programs to address this issue. In California, a prior drug felony cannot be the sole basis for denying a cannabis license. In Portland, Oregon a portion of cannabis sales tax revenue is spent on funding women-owned and minority-owned cannabis businesses (DPA).

Decriminalizing Personal Possession of Illegal Drugs in Oregon

On November 3, 2020, Oregon became the first state in the United States to decriminalize the personal possession of illegal drugs. By approving Measure 110, Oregon voters significantly changed the way drug possession violations are addressed. People found with smaller amounts of controlled substances (such as heroin, cocaine, or methamphetamine) are issued a Class E violation, which is punishable by a $100 fine. Alternatively, people in violation can have the fine waived if they complete a health assessment at an addiction recovery center. Measure 110 also created a new drug addiction treatment and recovery grant program funded by the anticipated savings due to reduced enforcement of criminal drug possession penalties, as well as cannabis sales tax revenues (Lantz and Neiubuurt 2020). Advocates for Measure 110 saw it as a way to eliminate drug policies that were having a disproportionately negative impact on Black and Indigenous People of Color. This law also shifted the societal response to drug use from a punitive, moralistic approach to one that involved treatment and compassion.

During the same election vote in 2020, Oregonians also approved Measure 109, which directs the Oregon Health Authority to license and regulate the manufacturing, transportation, delivery, sale, and purchase of psilocybin products and the provision of psilocybin services (Oregon Health Authority N.d.). Psilocybin is the main psychoactive component of magic mushrooms (Figure 11.18). This substance has been utilized for thousands of years in spiritual ceremonies in Indigenous cultures (Lowe et al. 2021). Psilocybin is considered a psychedelic hallucinogenic drug that produces both mind-altering and reality-distorting effects.

Following negative stigmatization of the substance due to its use within the hippie counter culture movement, in 1970, the federal government changed the classification of psychedelics (including psilocybin) to Schedule 1 drug, which ended all scientific research on psychedelics. Research interest in the therapeutic uses of psychedelics resumed in a 2004 pilot study from the University of California, Los Angeles, which investigated the use of psilocybin treatment in patients with advanced-stage cancer (Grob et al 2010).

Since then, significant amounts of research into the use of psilocybin to treat an array of health concerns, from anxiety to cluster headaches, have taken place. Measure 109 in Oregon required a comprehensive review of the scientific literature on psilocybin’s therapeutic uses. This review found research that suggests that psilocybin can reduce depression and anxiety. The FDA has designated psilocybin as a “breakthrough therapy” for the treatment of depression, which means that psilocybin treatment may be a significant improvement over existing therapies to treat depression Psilocybin therapy involves the administration of the substance in the context of counseling support in the weeks before and after dosing (Abbas et al. 2021). Though Oregon’s regulated psilocybin treatment programs will not be up and running until 2023, they offer hope to those suffering from mental health disorders for whom other treatments do not work. Oregon’s decriminalization of low-level drug offenses is revolutionary, but it follows the advice of national social justice advocates, who recommend this action to address systemic inequalities related to harmful drug use.

Community Collaboration for Drug Treatment

A final way to address the social problem of harmful drug use is to expand access to effective drug treatment. Expanding options takes collaboration by federal, state, and community partners to make a difference.

The Intersectionality of Drug Treatment

Socioeconomic status and race impact access to drug treatment. Most elective drug treatment programs require some form of payment for services. Those without insurance and without the financial means to pay will be unable to receive treatment. Researchers have also found that racial discrimination has prevented entry for Black and Indigenous People of Color into more desirable forms of drug treatment (Hansen 2015).

While some may actively seek drug treatment, others may be forcefully mandated to attend strong-arm or faith-based rehabilitation pro- grams. Sociologist Teresa Gowan asserts that these types of mandated rehab programs are used by the state to manage the poor. Poor individuals with a drug violation may be mandated to undertake forms of treatment that are designed to “transform basic behavioral dispositions and instill a new moral compass” (Gowan 2012).

At strong-arm rehab centers, all DWI (driving while intoxicated) and many low-level drug offenders are encouraged to define themselves as addicts, even if they may not actually have a substance use disorder. They are also punished for relapse and rewarded for a “cure.” Gowan found that cultural styles and tastes that were not middle-class were brought into the so-called therapeutic habilitation process and considered to be in need of reform. Bringing up the role of poverty or racism in one’s life is thought to be immature and evidence of the addict’s ego (Gowan 2012).

Race and class also play a role in determining which type of opioid use disorder treatment one will receive. Hansen (2015) found that BIPOC was often only offered the option of the less desirable methadone treatment, which requires near-daily visits to a clinic and a demeaning and constricting practice of surveillance (Bourgois 2000). In contrast, White middle-class individuals were more likely to be given the opportunity to receive buprenorphine treatment for their opioid use disorder. This type of treatment is more private and requires significantly fewer medical interactions. Hansen (2015) sees this systemic discrimination as working to maintain the race and class privilege of White middle-class individuals.

Increasing Drug Treatment Options in Local Communities

Drug treatment in Oregon is particularly lacking. Oregon ranks 47th among the 50 US states in access to treatment for substance use disorders. Treatment needs are significantly unmet. In fact, only 8.5% of teens and adults in Oregon who needed treatment received it (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Administration 2020). How might increasing treatment options impact the social problem of harmful drug use? Higher levels of social capital within a community might protect it from higher overdose rates. Social capital is defined as the social networks or connections that an individual has available to them due to group me social capital researchers measured social capital by looking at voting rates, the number of non-profit and civic organizations in a community, and response rates to the census (Zoorob and Salemi 2017). These are all indicative of one’s engagement with their community, as well as increased social linkages between people through community organizations.

Community connections can also decrease drug use. Research documents the relationship between experiences with racism and illicit drug use among Black women (Ehrmin 2002). This research shows that while socioeconomic class was a factor, it was not the sole determinant of drug use (Stevens-Watkins et al.2012). Instead, Black women used drugs less if they had a strong ethnic identity and were connected to their communities (Maclin-Akinyemi et al. 2019).

Increasing funding for drug treatment, including drug treatment facilities, harm reduction programs, and community-based drug treatment pro-rams can expand social justice for drug users. Community-based drug treatment programs serve over 53% of people in recovery (Bowser 1998). They include Twelve Step programs and other peer-led recovery groups. These community-based organizations may serve people with specific social identities, such as recovery groups for firefighters, queer people, or women, as examples. In addition, a recent study found that even when harm reduction or drug treatment services were available, they wouldn’t offer enough wrap-around services to their clients. For example, even though many clients were unhoused, most programs didn’t offer housing. Even when clients were parenting, the programs had no funding for childcare services (Krawczyk et al 2022).

One way to increase funding for drug treatment is through local ballot measures. Measure 110, which decriminalizes possession of small amounts of illicit drugs, was passed in the 2020 election in Oregon. This law increases state funding for drug treatment services.

Chapter adapted from: “Inequality and Interdependence: Social Problems and Social Justice (Kimberly Puttman et al.)” by LibreTexts is licensed under CC BY.