7 Topic: The Economics of Health Disparities

Learning Outcomes

- Analyze the social determinants of health, including factors like income, housing, education, and employment, and explain how they contribute to health disparities and inequities.

- Evaluate how systemic racism and historical policies have led to racial and ethnic health inequities in the United States, affecting access to resources and opportunities.

- Discuss the impact of economic instability, such as poverty, housing insecurity, and food insecurity, on health outcomes across different populations.

Health is influenced by a myriad of factors, many of them beyond genes or biology. Factors such as income and wealth, housing quality, access to greenspace, access to healthcare, education, stressful environments, and more – are often lumped into a category we call the Social Determinants of Health (SDOH). The U.S Department of Health and Human Services provides a broad definition as:

Social determinants of health (SDOH) are the conditions in the environments where people are born, live, learn, work, play, worship, and age that affect a wide range of health, functioning, and quality-of-life outcomes and risks.

Variance in these environments and conditions that people are born into and live in cause stark differences in health outcomes. Life expectancy overall is influenced by zip code. Life expectancy at birth can vary by 10 years or more between different census tracts within the same county (NCHS, 2022). Indeed, as the Vice President of the California Endowment (a non-profit health equity advocacy group) Dr. Tony Iton states: “When it comes to health, your zip code matters more than your genetic code.” (Iton, 2021).

Health Disparities

Health disparities refer to differences in health outcomes (morbidity and mortality) between populations that are not based in genetics or individual biology. Health inequities are defined as an increased risk of poorer health correlated with race/ethnicity, gender, sexual orientation, socioeconomic status, health insurance status, rural/urban residence or (geographical location), and housing status (U.S. DHHS, HRSA, Office of Health Equity., 2020). Although the terms “disparities” and “inequities” are often used interchangeably (even in this text), it is the inequities in health opportunities that often lead to the disparities we see in health outcomes of different groups. In other words, we are recognizing that there are differences in how long we live and what diseases affect us (and how seriously sick we become) that have more to do with social, economic, political, and environmental factors than any genetic or biological influence. Why do people in one zip code live longer than those in another? Why is income or education level such a strong predictor of health? These social determinants of health are perhaps the strongest predictors of overall population health. “Health inequities refer to inequalities that are unfair, unjust, avoidable or unnecessary, and that can be reduced or remedied through policy action”(U.S. DHHS, HRSA, Office of Health Equity., 2020). Pursuing health equity – providing opportunities for all to attain their highest level of health – is a paramount role for public health (Healthy People 2030, n.d.).

Race and Ethnicity

The concept of different races within the species homo sapiens is a social construct; it has no basis in genetics or biology (Yudell et al., 2016). Races are categorized as characteristics of an external phenotype (such as skin color, eye color, hair type), and/or as a cultural identity or inheritance. A person’s race may be a part of their own social identity, or could be applied to them by society, based on their appearance.

Ethnicity is different from race in that it is more associated with a cultural heritage, language, religion, customs, shared history, or attachments to ancestral land (Seabert et al., 2021). Ethnicity is also socially constructed, and an ethnic identity may change over time with different generations. For example, a person with dark skin may be treated by other members of society as Black (racially). Assumptions and stereotypes may be made about them, microaggressions aimed at them and they may experience discrimination for being Black. The same person may also identify as ethnically Nigerian-American. Their parents or grandparents may have immigrated from Nigeria, they may adopt and express various customs and cultural expressions of both Nigerian and American culture – and perhaps a Nigerian-American subculture. Another individual with light skin may check the box for “White” or “Caucasian” on government documents, and may be ethnically Armenian. Each person’s lived experience within society is influenced by all of their identities, whether the identity is ascribed to them by U.S. society, or owned and expressed by themselves.

How both race and ethnicity influence health outcomes via the social determinants of health has much more to do with racism, xenophobia, and ethnocentrism in American social, economic, and political structures than any influence from genetics, or cultural behaviors. (Genetic predispositions to specific health conditions that can be passed to offspring are covered briefly in chapter 9). Racial health disparities are not genetic predispositions to poor health. Ethnicities are poorly defined, complex, and fluid. Ethnicity in public health research often depends on self-identification with arbitrary classifications (such as “Hispanic” or “Asian”). Yet race and ethnicity are still used by the U.S. government in collecting census data, and still used in epidemiology – particularly to help identify health inequities that may be caused by systemic and structural racism, and Anglo/European-ethnocentrism (Bhopal, 1997).

Race and Ethnic Health Inequities

A recent report from the Office of Minority Health, an agency of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS), outlines how federal policies have caused and maintained structural disadvantages to obtaining long, healthy lives in minoritized communities. This report also uses the term minoritized groups rather than minority or minorities to further describe how structures and policies have affected populations, rather than these disparities being a result of numbers of a specific demographic in a population. (These terms will also be adopted in this text). The assertion is that racial and ethnic disparities in health and health outcomes are significantly caused or made worse by historical or existing governmental policies, and therefore a path toward health equity involves new federal policies and accountability (National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, 2023).

The United States’ early history of Native American extermination, land seizure, kidnapping of native children and required assimilation has caused, and continues to perpetuate significant health repercussions for American Indians and Alaskan Natives (AIAN). Concurrently, the forced immigration and enslavement of Africans, subsequent Jim Crow laws, and even purposeful public health abuses (such as the Tuskegee Syphilis Study), have negatively affected the health of Black Americans for centuries. Additionally, federal policies relating to immigration and social services also play a role in health disparities, particularly those experienced by immigrants and asylum seekers, and their children. Although health disparities are also correlated with poverty and lack of education, those racial and ethnic inequities exist at all socioeconomic strata – indicating that the explanation lies beyond income or education alone. A section in the report summarizes just some of the health inequities in America:

There are higher rates of childhood asthma among low-income households, higher morbidity and mortality from chronic diseases among individuals with lower educational attainment, and higher exposure to air pollution among residents of disinvested communities—disproportionately individuals who are racially and ethnically minoritized. Moreover, the effects of the structural determinants of health on many health outcomes persist when accounting for income and education (National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine., 2023).

According to an earlier DHHS Health Equity Report in 2019-2020, significant racial disparities in health and social determinants of health have persisted across the decades. Although measures like life expectancy and educational status have improved for all Americans, there are still differences in these and other measures between racial groups. Racially minoritized groups have twice or higher the poverty rates as non-Hispanic Whites do (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Health Resources and Services Administration, Office of Health Equity., 2020). According to the most recent report from the U.S. Census Bureau tracking poverty rates for the year 2022, the poverty rate for those identifying as non-Hispanic White or Asian was 8.6%, whereas it was 17.1% and 16.9% for those identifying as Black and Hispanic respectively, and 25% for American Indian and Alaskan Natives (Shrider & Creamer, 2023).

This disparity in poverty rates is also reflected in the increased likelihood of minoritized populations living in impoverished zip codes. Southeastern and Southwestern states tend to have the highest poverty rates, a trend which has remained consistent over time, and is consistent with higher unemployment rates in these areas. Neighborhoods that have been historically racially segregated as “non-White” have associations with lower life expectancy and higher rates of homicide, infant mortality, and all-cause mortality, as well as higher rates of mental distress, community violence, excessive drinking and smoking, and HIV prevalence (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Health Resources and Services Administration, Office of Health Equity., 2020). These neighborhoods often also have higher exposures to environmental toxins like air pollution and lead (Doctrow, 2022).

According to the KFF (formerly known as the Kaiser Family Foundation) health tracking polling, many disparities exist with how safe minoritized groups feel in their homes and neighborhoods, and how discrimination impacts everything from housing to healthcare. This foundation conducted a survey on racism, discrimination, and health in a representative sample of 6,000 Americans in 2023. Hispanic, Black, Asian and AIAN individuals are less likely to report feeling safe in their neighborhoods. About twice as many racially minoritized respondents reported a family member being victimized by violence as did White respondents. Also consistent with earlier surveys, minoritized groups are significantly more likely to have a family member who has experienced mistreatment from law enforcement (Artiga, 2023). “Nearly half of Black Americans say they have been afraid their life was in danger due to their racial background,” (Reich, 2022). All of these disparities impact health on multiple levels across the lifespan; not the least of which is the heightened chronic stress due to discrimination, racism, and poverty.

Systemic Racism

Systemic and structural racism cause disparities in access to goods, services, and opportunities using laws, policies, practices, or attitudes. Systemic racism is often hidden, and practices or social values are accepted as the norm without questioning whether racism had any influence on their creation. Below are two examples of how systemic and structural racism continue to impact racially minoritized communities and cause health inequities.

Systemic racism has influenced neighborhoods through redlining: a practice of segregating Black Americans into urban neighborhoods and denying them residential loans. Black neighborhoods were considered financial “risks” by banks and lenders. Newly-built housing tracts often came with contracts requiring that anyone who purchased one of the new houses could not sell it later on to folks from other races or ethnicities – thus keeping suburban communities segregated. Even when the Fair Housing Act of 1968 opened up FHA loans for Black Americans legally, the practice of discrimination continued on within financial institutions. At the same time, home prices continued to increase in the suburbs, which continued to keep loans out of reach for many (Rose, 2023). A majority of those communities that were redlined almost a century ago are still low income, minoritized neighborhoods. Since home ownership is one of the primary mechanisms of building wealth for the middle class, this had a generational effect on racial wealth disparities (Reich, 2019).

Structural racism also influences access to education and economic advancement via funding for public schools. Public schools are funded primarily by state taxes and local property taxes, with much smaller portions from federal funds or community fundraising. This means that if home values are lower in a particular neighborhood, their school district gets less money compared to a school district with higher home values. In those states that have approved them, voucher programs also redirect tax dollars from public schools into private, charter schools – cutting into public school budgets even further. Schools in lower income neighborhoods tend to have more trouble attracting and maintaining teachers, and they may spend more of their limited resources on safety measures and behavioral interventions rather than enhancing learning programs (Reich, 2023). In school, young Black men are more likely to receive harsher punishments, and schools are more likely to call the police when disciplining them – thus increasing the risk of incarceration and eroding trust (P. A. Braveman et al., 2022). In these ways and many others, both current and historic policies continue to create structures and systems that provide fewer opportunities for wealth and impact long-term health outcomes in racially minoritized neighborhoods.

Economic Stability

Economic stability refers to the ability to afford things like housing, food, and health insurance, and the social structures and built environments that come along with wealth. Economic stability can certainly be assessed with income levels, but income alone may not provide a complete picture. Other metrics like home ownership (which can be a surrogate for wealth), or self-reported stress about food or housing are also important ways to measure the effects of money on health. Population economic stability is certainly affected by macroeconomic and political factors such as inflation, unemployment rates, and the minimum wage. Individual changes in socioeconomic status such as job gain or loss, property ownership or loss, and even marriage or divorce can also be factors that impact health outcomes.

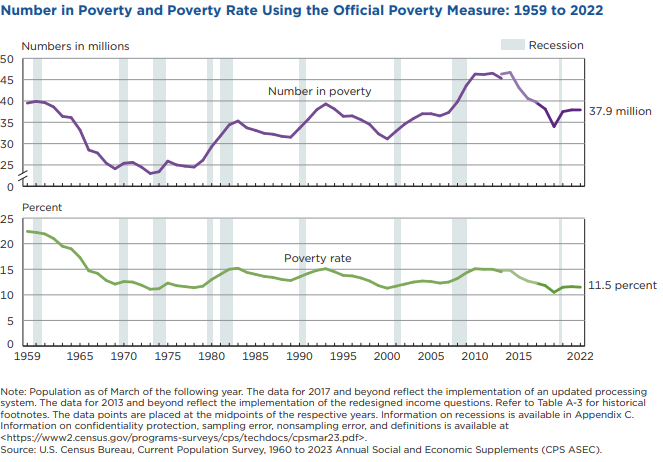

Poverty is a significant factor in many different health outcomes. Poverty in America is defined as an income at or below a certain standard set by the U.S. federal government, which changes over time due to inflation. In 2022, the poverty level for an individual annual income was set at $14,880, or $29,950 for a family of 4. This is up from $12,880 and $26,500 respectively just a year prior in 2021 (U. S. C. Bureau, 2023b). Over 37 million Americans currently live at or below the poverty rate by this official poverty measure, which in 2022 was 11.5% (as seen in Figure 22 below). Notably, these income limits do not change in different areas to reflect the geographic variance in the cost of living. So it may require an income significantly higher than the poverty rate to be able to afford housing and food in a larger metropolitan area where these things can be more expensive. Additionally, some folks who receive government assistance may not be factored into the official poverty measure, so a supplemental poverty measure (SPM) is also used as a metric to account for these factors. The SPM for 2022 was 12.4%, and although the official poverty measure did not change between 2021-2022, the SPM increased by 4.6% over that year (Shrider & Creamer, 2023).

Many of those living in poverty are children. Childhood poverty is calculated using the SPM which takes into account people receiving social assistance like the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP). There are also racial differences with poverty for children, with the highest poverty rates in Hispanic and Black children, and the lowest poverty rates in non-Hispanic White children. In 2020 and 2021, social assistance programs were expanded in response to the pandemic, which included SNAP and the Child Tax Credit (CTC). The latter specifically reduced childhood poverty significantly (in all groups) – lifting 5.3 million people out of poverty, including 2.9 million children (U. S. C. Bureau, 2022). In 2021 childhood poverty hit a historic low at 5.4%, but then climbed back up to 12.8% in 2022. The expiration of the expanded CTC benefits is at least partially to blame for this relapse in poverty (Parrott, 2023). Food and housing insecurity negatively impact childhood health in several ways; including poor nutrition, a lack of physical activity, behavioral and academic problems in school, and higher risk of health problems like obesity and type II diabetes ( U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Health Resources and Services Administration, Office of Health Equity., 2020).

Whether you have a lived experience of poverty or can imagine it, wondering if you’ll be able to pay rent, utilities, buy food, and medicine can be mentally and emotionally debilitating. Worrying about housing costs can cause severe psychological distress, and is associated with poorer self-reported health. Even risks of chronic diseases like heart disease, high blood pressure, and diabetes are associated with higher stress around housing affordability. Additionally, home ownership is often a proxy for wealth, so renters are more likely to experience this kind of stress than homeowners. The majority of renters who live in government-subsidized housing are women (⅔), and often these renters are single or divorced, and experience much higher distress levels than those who own a home. (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Health Resources and Services Administration, Office of Health Equity, 2020).

Obesity rates, diabetes rates, and sedentary rates increase inversely with wealth (American Diabetes Association). Wealthy people are more likely to engage in healthy behaviors like exercise and less likely to engage in unhealthy behaviors like smoking. Wealth in terms of home ownership also increases the social cohesion of a neighborhood, with those who own homes reporting more trust in their neighborhood. This social cohesion also results in more engagement in voluntary organizations and local activities (religious centers, sports, community activities, etc.). In fact, parents living in wealthier neighborhoods are far more likely to report social support of their community in watching out for each other’s children and helping each other out. People who own their home are also likely to live there for longer than if they were renting ( U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Health Resources and Services Administration, Office of Health Equity., 2020). Wealth and home ownership are thus strong factors in health and well-being outcomes for individuals and communities.

Employment

It is important to note that employment status has a significant effect on economic stability. Both unemployment and under-employment impact a person’s ability to pay their bills and their sense of security in meeting their basic needs. Underemployment includes intermittent unemployment, poverty wages, or being unable to find a job that matches or appropriately compensates the person’s education level and skill set. Part-time employment can also fall into this category, as many workers who would like to work full-time must take several part-time jobs instead. And, do these jobs pay a “living” wage – that is, can someone work the equivalent of full-time, or 40 hours per week, and afford rent and food based on their area’s typical prices? If not, a person may have to work overtime, juggle multiple jobs, live with several family members or roommates, and/or accept substandard living conditions (see Housing Instability and Quality below). Many low-wage jobs are also high-stress, which has an impact on mental health and a correlation with substance abuse (Employment – Healthy People 2030, n.d.).

Housing Instability

A lack of sufficient and quality housing affects health in both large cities and rural areas. Perhaps the first problem we think about with a lack of housing is homelessness, or a state of being unhoused. Although images of tent encampments on sidewalks are often what is portrayed on the news media to describe the “homelessness crisis”, the unhoused population includes more people than those visibly living on the street. Folks who have no permanent residence may be living out of their car, in hotel rooms, or “couch surfing” and staying with friends or family temporarily. They may also be living in temporary subsidized housing or staying in shelters overnight. Housing status can be dynamic and change rapidly over time, so it can be difficult for public health officials to get a true count of housing needs in a particular area. For example, the Los Angeles Homeless Services Authority (LAHSA) conducts a point-in-time count of unhoused individuals over 3 days, twice per year, which includes those in shelters, transitional housing, and hospitals, as well as a visual count conducted by volunteers across the city (Greater Los Angeles Homeless Count, 2024). This may still undercount some individuals who lack permanent housing, or are housing insecure – which can also mean being at risk for losing housing within the next couple of weeks. Housing instability is obviously a complicated problem.

Both a lack of permanent housing and housing insecurity can cause significant physical and mental stress. Those without housing are at higher risk of being assaulted, are likely to go hungry and have food insecurity, and lack access to basic hygiene facilities – which increases risks of infectious disease and malnutrition. The psychological stress of housing insecurity can be debilitating; anxiety, depression, and substance abuse are common. Yet American society adds to these hardships by stigmatizing and dismissing those who are unhoused as “lazy” or “drug addicts” (Bhattar, 2021). Local governments often take steps to remove homelessness from the sight of other residents, many times without actually providing sufficient housing for those affected. Some attempts to convert or build temporary housing facilities are met with strong opposition from local residents due to this stigma (Canadian Observatory on Homelessness, 2021). Hostile architecture like bars in public benches, or pylons under bridges are built to make it impossible for people to find shelter in those locations. Some local governments make camping on the street illegal, increasing the likelihood of hostile police interactions and incarceration for the unhoused. Assaults by private individuals and police officers on the homeless have been documented (Bhattar, 2021).

Individuals experiencing a lack of housing are not a monolith, yet homelessness does tend to affect marginalized groups at higher rates. Some are suffering from mental illness and addiction. Veterans suffering with post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) often lack housing and may have other disabilities as well. There are also those who have one or more jobs and their wages are insufficient to support them. Other individuals have been kicked out of a family home, or left abusive relationships. LGBTQ+ youth can be at a high risk of homelessness, and victims of domestic abuse often face homelessness while leaving an unsafe relationship. A lack of affordable housing in many areas of the U.S. exacerbates these problems (Bhattar, 2021). College students are also often among those lacking housing. For example, a CA State Assembly report found that 5% of UC students, 10% of CSU students, and 20% of community college students in CA reported experiencing some form of housing insecurity – often from a lack of affordable housing close to the campus they are attending (Burke, 2022). Lacking those basic necessities can have a significant impact on the academic performance of those students.

Housing Quality

Substandard housing is also a public health issue. The U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) considers substandard housing to be any permanent residence lacking hot and cold water, sink, toilet, or shower, and kitchen facilities like a stove, refrigerator, and sink with running water. Living in a place without any of these utilities can affect personal hygiene, the ability to cook fresh and healthy meals, and ultimately increases the risk of both infectious and chronic diseases. A recent report estimates that substandard housing affects over 1.5 million people living in cities and over 368,000 people living in rural areas. American Indian and Alaskan Natives have the highest rates of lacking appropriate plumbing and kitchen utilities, followed closely by rural communities and people with disabilities (Swendener et al., 2023).

Even if housing has adequate plumbing and kitchen facilities, there may be other issues that impact health such as rodent or insect infestation, mold, lack of heating or cooling, or exposure to household toxins like lead or formaldehyde. Even low levels of lead exposure can have significant effects on neurodevelopment in children. Dilapidated structures pose higher risks for injuries for children, older adults, and people with disabilities (Quality of Housing – Healthy People 2030, n.d.).

A lack of disposable income can make it difficult to pay for home repairs, and landlords can sometimes shift responsibilities to tenants – particularly in competitive rent markets. One report found that even prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, nearly 15% of rental homes either needed substantial repairs, had rodent infestations, or lacked some resource (like heating or water), and these homes were more likely to be rented to the poorest – and most rent-burdened families (U.S. Government Accountability Office, 2020).

Other issues around housing include struggling to pay rent or a mortgage, spending more than 30-50% of income on housing, overcrowding, and having to move frequently (Housing Instability – Healthy People 2030, n.d.). Housing is considered “affordable” when it costs 30% or less of the household income (Braveman et al., 2011). Children who have to move more than 3 times in one year have much poorer health and are also less likely to have health insurance. Overcrowding increases the risks of infectious disease transmission and can also impact mental health. The COVID-19 pandemic only highlighted the impact of overcrowding and poor ventilation in living spaces. All of these factors can impact both physical and psychological health of individuals and the social cohesion of a community. Over their lifespans, people living in areas of poverty or experiencing homelessness have significantly worse health outcomes (Housing Instability – Healthy People 2030, n.d.).

Food Insecurity

Food insecurity describes not only experiencing the physical pain of hunger, but also not knowing when or where the next meal will be, and/or a reduction in the quality and desirability of food. In fact, the USDA describes two levels of food insecurity as being low food security and very low food security depending on whether or not a person has limited access to only quality or both quality and amount of food (Food Insecurity – Healthy People 2030, n.d.). Food insecurity is also associated with obesity, diabetes, and other chronic diseases that are often caused by overconsumption of calories. This is sometimes referred to as the food insecurity paradox. Although to date research has not identified a clear reason for this, one of the proposed mechanisms focuses on food cost vs. quality. For example, a person may have adequate access to total calories (or too many calories), yet those calories may be provided by highly processed foods with very little nutritional value. They may not be able to purchase fresh fruits and vegetables, meat, fish, eggs and dairy products, and/or their meals might mostly consist mostly of canned, frozen or prepackaged foods, or meals from vending machines, fast-food restaurants, and convenience stores. These cheaper, more convenient food products also tend to be higher in fat, sugar, salt, and calories. Thus, although in developing countries food insecurity is associated with dangerously low body weight, in wealthier countries like the U.S. food insecurity is associated with obesity – particularly in women (Carvajal-Aldaz et al., 2022). In terms of other health effects, certainly worrying about the next meal or being able to afford food impacts a person’s stress level and their mental health as well (Food Insecurity – Healthy People 2030, n.d.).

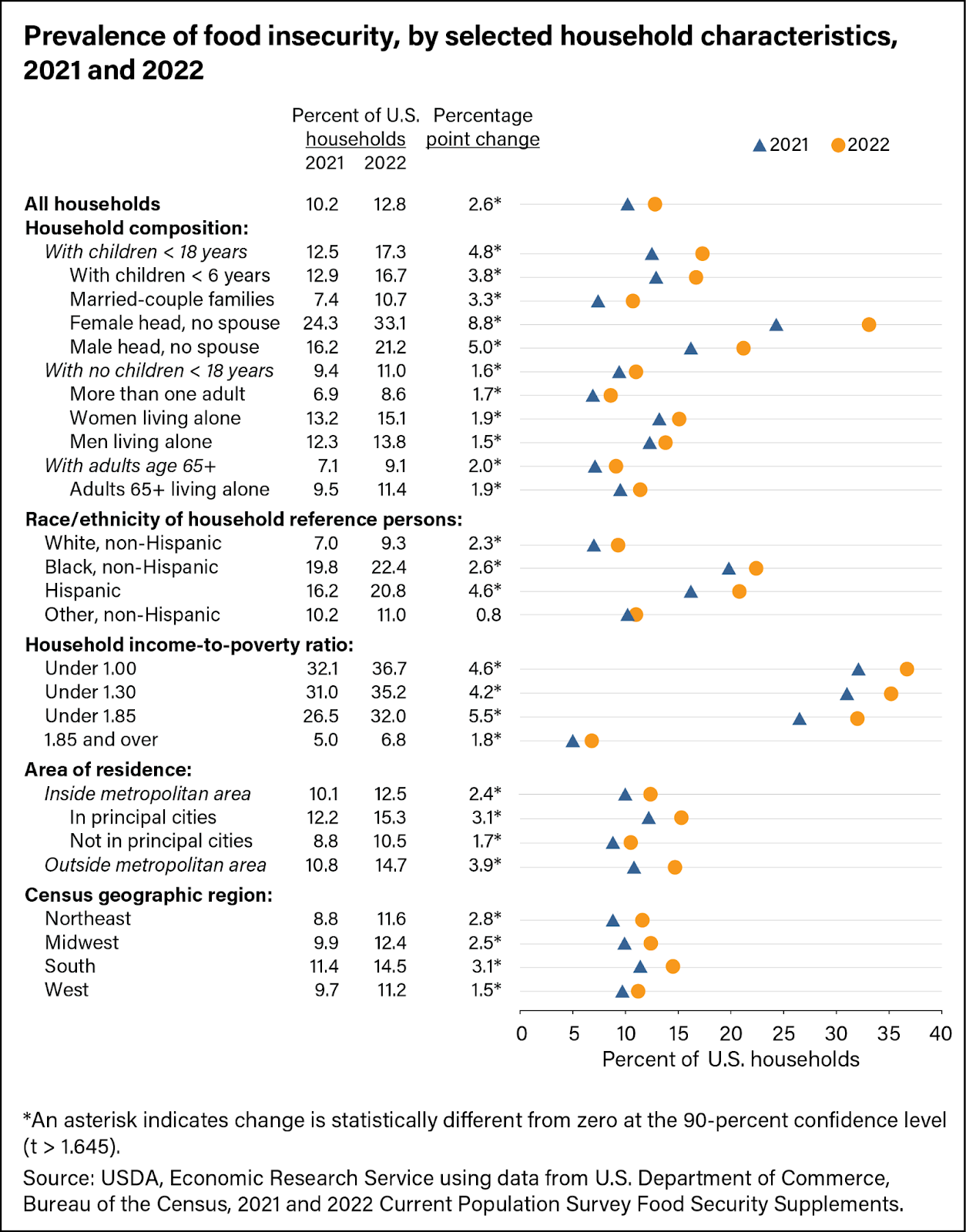

In 2022, food insecurity affected 12.8% of households, which is a significant increase since 2021, when food insecurity was at 10.2%. Rates of food insecurity were the highest – and increased the most between 2021 and 2022 – for single mothers with children under 18 (USDA ERS, 2023). See Figure 23 below.

Education Access

On the whole, higher levels of education are linked with better paying jobs and better health over the lifespan. Graduating from college decreases the risk of future unemployment (and thus many of the health factors that come with economic instability), and college graduates report better health than those who only complete high school. College education is more often required for white-collar jobs, which tend to pay better wages and are more likely to provide health insurance benefits. This also means college graduates may be able to afford better quality housing, and have more access to healthy dietary patterns and leisure-time physical activity. Unhealthy behaviors like smoking and drinking excessively are lower in more educated populations (Enrollment in Higher Education – Healthy People 2030, n.d.).

Education levels of parents are also correlated with the health of the rest of the family. Childhood obesity is negatively correlated with the education level of the head of the household (HHS reports). If parents have higher education, children are less likely to experience adverse childhood experiences (ACEs). These types of experiences can include trauma from physical or sexual abuse, neglect, witnessing a family member use drugs or have mental health problems – including attempting or committing suicide – or having a family member become incarcerated. They can also include witnessing violence in the home or community, becoming homeless, or experiencing stress from housing and food insecurity (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Health Resources and Services Administration, Office of Health Equity., 2020).

As mentioned earlier, racial disparities in health and life expectancy persist across educational strata. However, one increasingly common cause of death primarily affects white, non-college educated, middle-aged men, who live in mostly rural areas and small towns. Correlated with the decline in blue-collar job opportunities in middle America, so-called “deaths of despair” have increased over the last decade. These include deaths from suicide, drug (mostly opioid) overdoses, and liver disease, all associated with physical and psychological pain (Scutchfield & Keck, 2017). This is a tragic example of a combination of social determinants of health converging: unemployment, poverty, and a lack of access to healthcare (mental health care in particular), all contributing to higher rates of depression and substance abuse.

High School Graduation and Enrollment

Graduating high school is often used as a key metric since it is associated with better economic opportunities. Most jobs – even entry level, minimum wage jobs – require at least a high school diploma or equivalent. Dropping out of high school is associated with other social determinants of health such as poverty and unemployment, but also health outcomes such as higher risk for chronic disease. Teens who have gotten pregnant during high school are more likely to drop out, as are students who have less support for their education from parents. A perception of safety and caring in the classroom is also important. Students are more likely to complete high school when they feel like their teachers are invested, and don’t apply unfair punishment or discipline within the classroom (High School Graduation – Healthy People 2030, n.d.).

In recent years, high school completion rates have improved, however disparities still exist. For example, in the 2019-2020 academic year, the graduation rate was 87%, which is the highest it was in 8 years. Asian/Pacific Islander and White student graduation rates (93% and 90%) were still the highest compared to Hispanic (83%) Black (81%) and American Indian/Alaska Native (75%) (COE, 2023). And these racial disparities continue into college enrollment. According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) in October of 2022, 62% of 16-24 year olds who had graduated high school the year prior were enrolled in college. This percentage was not a significant change from the 2 years prior, but prior to the pandemic in 2019 the college enrollment percentage was just above 66%. Women are also significantly more likely to go to college, with 66% of young women and only 57% of young men enrolling. Enrollment rates in 2022 were highest for Asians (72%), slightly lower for Blacks (64%) and Whites (62%) and lowest for Hispanics (58%) (College Enrollment and Work Activity of Recent High School and College Graduates Summary, 2023).

Higher education can have many benefits for both income and health across the lifespan. Although there are always a small percentage of those with a high school diploma that make more money than bachelor’s degree holders, and a small percentage of bachelor’s degree holders that make more than graduate degree holders, the general trend for the majority of the population favors college educated individuals getting higher earnings with each level of degree (associates to doctorate/professional degrees) (The College Payoff: More Education Doesn’t Always Mean More Earnings, 2021). Higher paying jobs are often less dangerous, can lead to growing wealth, better housing, and often come with more reliable access to health insurance and better retirement potential. College graduates are also less likely to engage in harmful health behaviors like excessive drinking, and more likely than their non-college educated peers to adopt positive health behaviors like exercising and getting routine health screenings (Enrollment in Higher Education – Healthy People 2030, n.d.)

Nutrition Access

Food insecurity is associated with long term health consequences such as obesity and a higher risk of chronic diseases. This may be because food insecurity does not only include potentially skipping meals or not getting enough to eat, it also includes being forced to opt for cheaper, less-healthy food items. Access to healthy nutrition includes both the availability of healthy foods and their cost.

In order for a person to engage in healthy behaviors, they first must have an environment that allows for those behaviors. Perhaps nowhere is this more obvious than with health-supporting nutrition. According to the USDA, a healthy dietary pattern includes fruits and vegetables, grains (particularly whole grains), low-fat and fat-free dairy products, protein foods (including meat, eggs, and plant-based protein sources), and oils. Eating patterns that include these types of foods are associated with lower rates of chronic diseases including heart disease, diabetes, and some cancers. Epidemiological evidence points to higher rates of obesity and diabetes in neighborhoods with fewer fresh produce sources and more fast-food restaurants. Children who attend schools with a plethora of fast-food chains within ½ a mile tend to eat fewer fruits and vegetables, drink more soda, and are more likely to be obese than those who attended schools without fast-food nearby. Low-income and racially minoritized communities tend to also have fewer grocery stores in their neighborhoods, and have to travel farther to purchase fresh produce (Access to Foods That Support Healthy Dietary Patterns – Healthy People 2030, n.d.). This has led to the theory of “food deserts”; geographic locations around the U.S. where healthy food options are scarce, or residents have to travel long distances to reach a grocery store. These are not limited to urban areas either – ironically, people living in rural farmlands may also have to travel long distances to obtain a variety of fresh produce and protein foods. Rural food insecurity rates are similar to the high rates in inner cities (Rural Hunger and Access to Healthy Food Overview, 2024). Additionally, “food swamps” refer to areas replete with fast-food restaurants. Some studies indicate that living in a food swamp influences obesity rates even more so than food deserts. A neighborhood can be both a “food desert” and a “food swamp” at the same time (L. D. Burke & Weill, 2023).

Food prices tend to rise with general inflation, but can also outpace inflation particularly for specific food items. According to the USDA, the Consumer Price Index for foods increased dramatically in 2022 at around 10%, above the overall average increase in prices for other goods, and the largest increase in several decades (Consumer Price Index: 2022 in Review: The Economics Daily: U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, n.d.). This price increase was less during the following year, yet the costs of healthier foods have long been higher than the prices of less healthy, fast-foods or highly processed foods. Furthermore, people who live in low-income communities may pay higher prices for limited fresh produce options at convenience stores than those who live in more affluent communities with more large grocery stores (Access to Foods That Support Healthy Dietary Patterns – Healthy People 2030, n.d.). Fast food options and pre-packaged foods are also convenient for people who may not have time to prepare or cook whole foods purchased from a grocery store. The time-cost of healthy food becomes increasingly important to those who work multiple jobs, have long commute times, are caregivers, and/or those who have a disability.

Chapter adapted from: “Public Health 101” by LibreTexts is licensed under CC BY.