5.1 Social Determinants of Drug Use, Misuse, and Involvement

Christy Bazan; Brandi Barnes; Ryan Santens; and Emily Verone

Introduction

Why do some people use drugs, while others do not? Why do patterns of drug use for some people escalate to drug misuse? And, further, why do some individuals become involved in the cultivation, manufacture, distribution and sale of illicit drugs, despite knowing these behaviors carry with them increased risk of involvement in the criminal justice system?

While your own behaviors may contribute to drug use and misuse, the decision to use and misuse drugs is now understood to encompass complex behaviors situated within a matrix of ecological interaction occurring at multiple levels. Individuated treatment approaches centered on individual behavior via health beliefs, self-efficacy, or reasoned action (Rhodes, 2002) are ill equipped to address the generative interactivity across the biological, familial, sociocultural, economic, and physical environments (Thomas, 2007). These social-ecological factors are comprised of determinants that, as we will see throughout this module, disproportionately influence drug-related harms to particular groups of people and communities (World Health Organization, 2010).

Learning Content

Use and Misuse of Illicit Drugs, Alcohol, and Tobacco: Demographic Trends

As we begin to discuss in detail the social determinants of drug use, misuse, and involvement (e.g., cultivation, manufacture, distribution and sale of illicit drugs), it is important to have a clear sense of the broad demographic patterns of use and misuse of licit and illicit drugs in America.

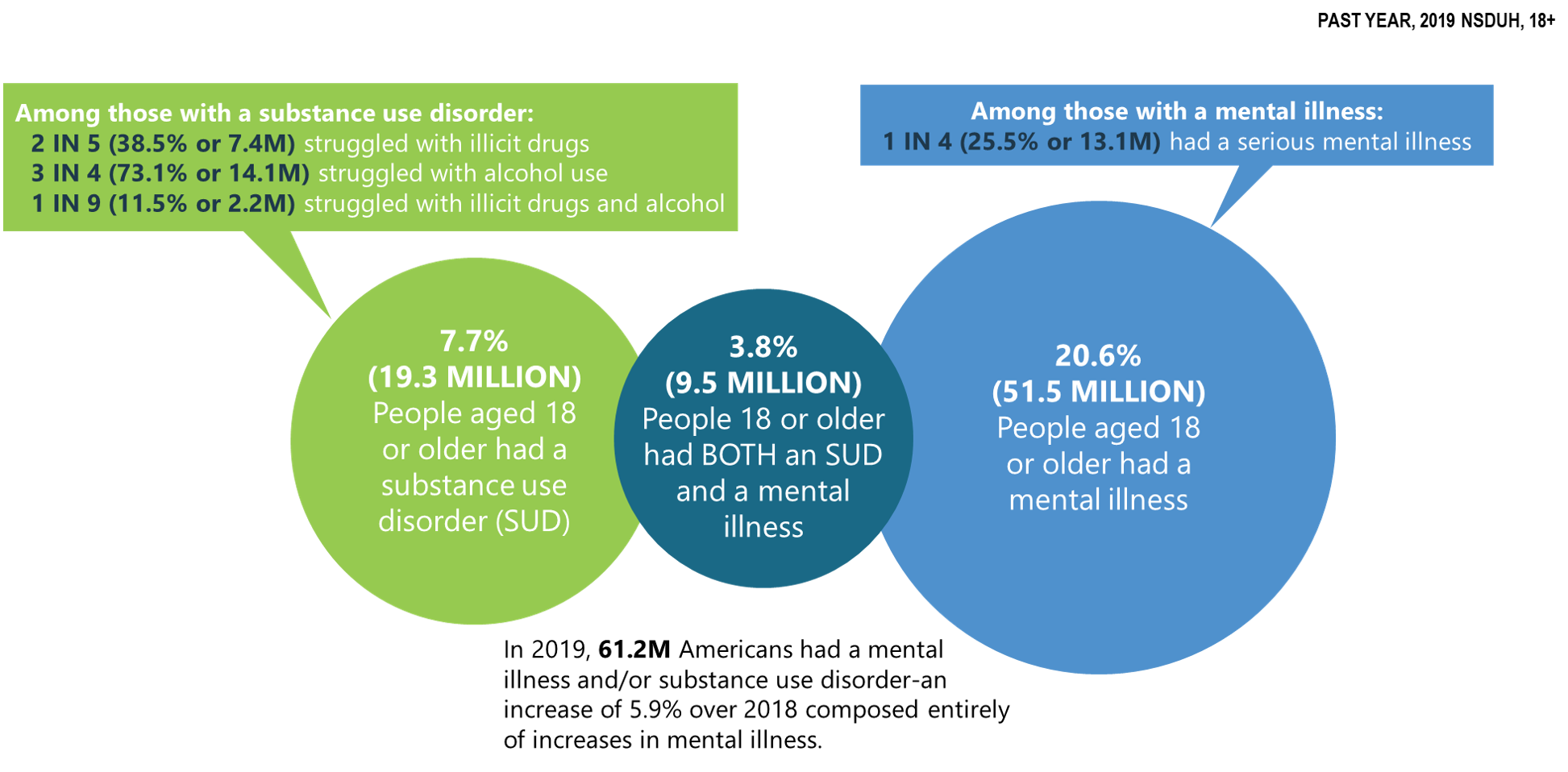

Mental Illness and Substance Use Disorders in the U.S.

Chart 5.1 – Chart from The National Survey on Drug Use and Health: 2019

Education

Educational attainment is not generally a reliable predictor of illicit drug use among adults aged 26 or older within the past year. This is demonstrated by the fact that adults who have graduated from college generally have lower rates of illicit drug use (17.4%) than those who have some college experience or an associate’s degree (21.2%), whereas, oddly, both of these “college experience/graduation” groups have higher rates of illicit drug use than adults whose highest level of educational attainment is high school graduate (17.2%) or less than high school (16.3%).

Notably though, with-in group rates, i.e. rates within the same group, of illicit drug use for 3 out of 4 of these educational attainment groups showed statistically significant increases from 2018 to 2019. In that timeframe, illicit drug use increased for adults who did not graduate from high school (13.8% to 16.3%), high school graduates (15.5% to 17.2%), and adults with some college or an associate’s degree (19.6% to 21.2%); whereas the change among college graduates was not statistically significant (Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality, 2020). What this tells us is that although graduating from college does not appear to impact whether or not you will use illicit drugs versus a person with less education, the rates of illicit drug use among college graduates is relatively stable, whereas it seems to be increasing for those with less educational experience.

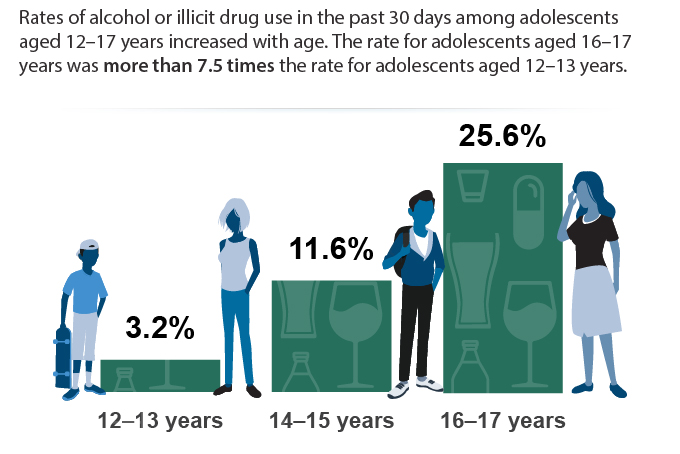

Adolescents

Chart 5.2 – Alcohol or Illicit Drug Use Among Adolescents in the Past 30 Days in 2017

College-Aged Adults

Findings from a 2019 national survey on drug use among college-age adults administered by the Institute on Social Research revealed:

- Cigarette smoking continued a downward trend, with 7.9% of college students reporting having smoked in the past month. Among their peers who are not in college, 16% reported having smoked in the past month, an all-time low.

- Binge drinking (five or more drinks in a row in the past two weeks), which has been declining gradually over the past few decades, showed no significant changes for young adults attending or not attending college. In 2019, 33% of college students and 22% of same-age adults not in college reported binge drinking. High-intensity drinking (10 or more drinks in a row in the past two weeks) has stayed level at about 11% since 2015 for people between the ages of 19 and 22, regardless of college attendance.

- Prescription opioid misuse continued to decline, with 1.5% of college students and 3.3% of those not attending college reporting non-medical use of opioids (narcotic drugs other than heroin) in the past year. This represents a significant five-year decline from rates of 4.8% and 7.7%, respectively, in 2014.

- Amphetamine use continued to decline, with 8.1% of college students and 5.9% of non-college respondents reporting non-medical use of amphetamines in the past year.

- While cigarette use is down, vaping both nicotine and marijuana is increasing among college aged students regardless of whether they are enrolled in college.

Overall, for college-aged adults many drug and alcohol use and misuse categories continue to show downward trends (e.g. cigarette smoking, prescription opioid misuse, amphetamine use), while others remain unchanged (e.g. binge drinking) or are increasing (e.g. vaping both nicotine and marijuana).

Further, there are no clear relationship patterns regarding whether or not college attendance for college-aged adults impacted drug and alcohol use and misuse. In some cases, such as cigarette smoking and prescription opioid misuse, college-aged adults not enrolled in college reported rates of use 2 times higher (16% smoking; 3.3% opioid misuse) than their college-enrolled counterparts (7.9% smoking; 1.5% opioid misuse). In the opposite direction, rates of binge drinking and amphetamine use were higher for college-aged adults enrolled in college (33% binge drinking; 8.1% amphetamine use) when compared with those not enrolled in college (22% binge drinking; 5.9% amphetamine use). (Schulenberg, J. E. et al., 2020).

Employment

Employment status affects current illicit drug use, with unemployed adults reporting the highest rates of use.

Among adults aged 26 and older, the rates of illicit drug use within the past year for those who were unemployed (30.3%) were 47.1% higher than those working full time (20.6%), 62% higher than those with part-time (18.7%) employment, and more than twice the rates of those whose employment status was “other” (13.9%), which includes students, persons keeping house or caring for children full time, retired or disabled persons, or other persons not in the labor force.

These data show important findings that those who are unemployed use illicit drugs at much higher rates than all other levels of employment. The severity of the negative impacts of unemployment on illicit drug use, however, becomes much clearer when examining the role of unemployment as a factor for an illicit substance use disorder (substance use disorder involving an illicit drug). When compared with all other levels of employment status, adults 26 or older who are currently unemployed report rates of illicit substance use disorder (9.1%) at more than four times the rate of all other employment levels: full-time (2.1%), part-time (2.1%), or “other” (1.9%) (Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality, 2020).

Generally, unemployment tends to increase the likelihood of illicit drug use and misuse.

Poverty

As we examine the rates of illicit drug use stratified by poverty, it is important to first understand the poverty thresholds for a specific household size within a particular year, as the poverty threshold increases or decreases depending upon household size and can change year to year with inflation.

The poverty threshold for a household of 4 in 2019 was equal to a total annual household income of $25,750.00. Poverty threshold levels for statistical indices in 2019 were:

- less than 100% if the total annual household income for a household of 4 is below $25,750,

- 100-199% if the total annual household income for a household of 4 is between $25,750.00 and $51,242.50, and

- 200% or more if the total annual household income for a household of 4 is more than $51,500.

Rates of illicit drug use and illicit drug use disorder tracked against poverty thresholds for adults aged 18 or over show a gradient pattern of use and dependence with the highest rates associated with the poorest adults, whereafter the rates decline as poverty decreases (or total annual household income increases). Adults 18 or over living in households at less than 100% of the poverty threshold report rates of illicit drug use in the past year (27.2%) at levels nearly 20% higher than those at 100-199% of the poverty threshold (22.9%), and 40.2% higher than their most affluent peers (2.4% in the 200% or more category).

As observed when fielding patterns of illicit drug use and dependence related to unemployment, increased drug use can lead to increased dependence. This is also the case regarding poverty where the poverty level (less than 100%) reporting the highest use also reported the highest rates of illicit drug-use disorder. In other words, just as drug use and misuse was the highest for those who were unemployed, similarly, it is the highest for those who suffer from poverty. Among adults aged 18 or over, persons living in households at less than 100% of the poverty threshold reported illicit substance use disorder (5.3%) at rates 60.6% more than those at 100-199% of the poverty threshold (3.3%), and more than twice their more affluent peers at 200% or more of the poverty threshold (2.4%). (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2019; Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality; 2020).

Criminal Justice System Involvement

Criminal justice system involvement is also strongly correlated with use and misuse of illicit drugs and alcohol. Adults aged 18 or older who were placed on parole or other supervised release from prison in the past year report using illicit drugs in the past month at more than 2.5 times the rate of individuals who are not on parole or supervised release from prison (30.8% versus 13.3%, respectively). When considering the use of more severe illicit drugs (excluding marijuana from the illicit drug category), this difference (16.7% parole/supervised release) increases to nearly fivefold that of individuals not on parole or supervised release from prison (3.4%). Following these trends, rates of heavy alcohol use for those who are on parole or other supervised release from prison in the past year (12.6%) are twice that of adults who are not on parole or supervised release from prison (6.3%). (Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality, 2020)