2.2 Date & Mate Selection

Seventy years ago, individuals often chose their partners based on their parents’ approval, the perceived health and morality of the person, and their economic stability. Today, however, we often seek soul mates in our partners. What caused this shift in how we approach selecting a mate? The changes in society over this time period played a significant role. Before examining these changes, let’s clarify the purpose of dating and what we aim to achieve through it.

Marriage

As mentioned, seventy years ago and continuing through the 1960s, people typically sought a partner primarily to start a family. They aimed for what was known as an institutional marriage, often referred to as a “good enough marriage,” which adhered to clearly defined gender roles, reflecting functionalist ideas. During this period, marriage was not primarily about love but rather about establishing a family together. The main objective was marriage itself, particularly to have children, and the means to achieve this was to settle down and start a family as soon as possible. There was little emphasis on finding the perfect partner; instead, the focus was on promptly starting a family. Getting married and becoming a parent were seen as markers of adulthood. For both men and women of that time, marriage and parenthood were the primary pathways to achieving adult status in society. For men, becoming a husband and father allowed them to fulfill the role of breadwinner, showcasing their masculinity through financial responsibility for their dependents. This transition to adulthood was considered unlocked through marriage. For women, marriage was seen as a means to become mothers and fulfill traditional feminine roles. The significance of marriage extended beyond personal feelings of love; it was viewed as a crucial economic and political institution. As Coontz (2006) aptly stated, marriage was too crucial an economic and political institution to be based solely on something as irrational as love.

In the past, there were limited ways for young people to transition into adulthood, so marriage often followed just six months of dating. The rush was to gain independence from parental oversight and start the next chapter of life. Back then, love was understood within the framework of traditional gender roles, rather than appreciating the unique qualities of the individual partner. This stands in sharp contrast to today’s approach, which prioritizes individual desires. The rise of the soulmate marriage model reflects the increasing emphasis on personal emotional and romantic fulfillment, paralleling the growing individualism in the United States and a shift away from communal values.

The soulmate marriage model is driven by a desire for passionate love, focusing on personal fulfillment rather than solely on traditional societal roles like procreation. Dating is now viewed as a journey toward self-discovery and happiness, rather than solely a means to start a family. In 2024, we have the luxury of taking more time to explore relationships before rushing into marriage, allowing us to search for ‘the one’ at our own pace. However, while soulmate marriages offer the potential for great fulfillment, they also carry a high risk of disappointment. In our current society, we expect our partners to fulfill roles that were once provided by an entire community: offering a sense of belonging, identity, continuity, transcendence, and mystery, all within one person.

View the video provided below to witness Stephanie Coontz’s portrayal of the evolution of marriage, comparing its past and present states. Stephanie Coontz is renowned as one of the leading authorities on marriage in the United States.

Dating

Take a moment to glance around your classroom. How many single people do you think are sitting there? In simpler terms, how many people in the same room do you think are currently unattached? And of those, how many do you find attractive enough to consider as a potential date, and how many do you instinctively feel you’d probably never date? These are the kinds of questions and answers that researchers explore when studying dating and mate selection. But before we delve into this, it’s crucial to recognize that our perceptions of attractiveness are shaped by societal norms, culture, and our own personal experiences.

The concept of dating as we know it today emerged during the 20th century. Dating involves meeting and spending time together to get to know one another. Before dating became widespread, courting was the norm in the United States. Courting, characterized by strict rules and customs, transitioned into dating thanks to the widespread use of automobiles following the Industrial Revolution. The newfound mobility provided by automobiles allowed young people more freedom, often away from the watchful eyes of their parents for the first time. With the shift from agrarian lifestyles to industrial work, love rather than practical necessity became the primary basis for marital relationships. Nowadays, dating takes on various forms, including traditional couple outings, group activities, online platforms, apps, and casual encounters.

In the United States, there are millions of individuals aged 18-24, which is considered prime dating and mate selection age. According to the National Center for Education Statistics (NCES), approximately 30.6 million people fell into this age group in 2017, accounting for around 9.4% of the U.S. population. Does this mean there are potentially millions of suitable mates out there? In theory, yes, but realistically, it would be impossible for anyone to interact with such many people in their lifetime. Dating and mate selection aren’t about quantity but rather about finding quality and intimacy in relationships.

When we encounter others, we subconsciously categorize them as either potential dates or not based on societal norms of attractiveness and suitability. This process, known as filtering, involves various criteria, including physical appearance, mutual acquaintances, and personal preferences.

Propinquity refers to the geographic closeness between potential partners. It’s the nearness you might feel when living in the same dorms or apartment buildings, attending the same university or college, working at the same job, or being part of the same religious community. Essentially, it means being in the same place at the same time, breathing the same air. Proximity is important because the more you see or interact with someone, whether directly or indirectly, the more likely you are to view them as a potential partner. Increased contact increases the likelihood of seeing someone as dateable.

Attraction and the assessment of physical appearance are subjective and vary from person to person, influenced by cultural standards of attractiveness. What one person finds attractive may not be what others find appealing. However, there are certain biological, psychological, and socio-emotional factors related to appearance that generally make an individual more attractive to a wider range of people. These factors include possessing slightly above-average desirable traits and facial symmetry. Nevertheless, societal norms play a significant role in shaping perceptions of attractiveness.

According to the Centers for Disease Control, the average height and weight for men and women in the United States are as follows: men are approximately five feet ten inches tall and weigh about 177 pounds, while women are about five feet four inches tall and weigh about 144 pounds (Sampson and Brazier 2023). Have you ever compared yourself to these averages or to people you know? Many of us tend to gauge our own attractiveness based on such comparisons. Understanding that we subjectively assess our attractiveness is crucial because it often shapes our choices in dating partners, as we tend to limit our options to those we perceive to be in our same attractiveness category.

If you are six feet tall as a man or five feet eight inches as a woman, you are slightly above the average height. For cisgender men, possessing what society deems “manly” facial features (such as a strong chin and jaw, along with some upper body musculature, and a slim waist) can make them more universally desirable. Conversely, cisgender women with larger eyes, softer facial features, a less prominent chin, fuller lips, and an hourglass figure tend to embody more culturally desirable traits. Essentially, individuals who fit into society’s norms of attractiveness are often perceived as more appealing.

But what if you don’t possess these universally desirable traits? Are you automatically excluded from the dating and mating pool? Not necessarily. One principle that significantly influences how we choose our partners is homogamy. Homogamy refers to the tendency for individuals to seek out partners who are similar to them in terms of attractiveness, background, interests, and needs. This tendency holds true for most couples as they typically pair off with someone who shares more similarities than differences with them. While it’s commonly said that opposites attract, research suggests that similarities in a relationship can indirectly contribute to its long-term quality by minimizing disagreements and fostering mutual understanding.

Conversely, heterogamy involves dating or pairing with individuals who possess differences in traits. While all of us engage in relationships with both heterogamous and homogamous individuals, there tends to be more emphasis on the latter over time, especially after commitments are made. Couples often find themselves developing more similarities as they spend more time together, adopting similar mannerisms, interests, and even dressing alike.

Abraham Maslow (1970), one of the most influential psychologists of the mid-20th century, introduced the concept of the Hierarchy of Needs, depicted in his famous pyramid. Maslow’s theory sheds light on how and why we choose our partners by focusing on how they fulfill our needs. For example, individuals from dysfunctional families may be attracted to partners who can provide the nurturing and support they lacked in childhood. On the other hand, those from supportive backgrounds may seek partners who offer growth and support in intellectual or self-actualization areas of life. While it may seem self-centered, our choices in dating and mating are often based on what we perceive we can gain from the relationship or how our needs can be met.

ANALYZING FAMILY STRUCTURES

Dating & Courtship

Compare the practices of courtship and dating. Describe how industrialization and consumerism brought about changes in how people explore relationships. Do you think courtship has evolved for better or for worse? Qualify your answer with examples.

“Dating & Courtship” by Katie Conklin, Lemoore College is licensed under CC BY 4.0

Finding a date

Surprisingly, nowadays, online dating has become the most common method for people to connect with each other. While traditional ways of meeting, such as through friends, family, or community gatherings, have been on the decline, the trend of meeting online has been steadily rising. According to a recent study conducted by Stanford sociologist Rosenfeld, which analyzed data from a nationwide survey of American adults in 2017, it was found that approximately 39 percent of heterosexual couples reported meeting their partners online. This is a significant increase from the 22 percent reported in 2009 (Shashkevich 2019). Take a look at this excerpt from the Stanford News discussing Rosenfeld’s findings.

Mate Selection

The social exchange theory, along with its rational choice formula, sheds further light on the process of selecting a partner. We aim to maximize the benefits and minimize the drawbacks in our choices of a mate. It’s like a simple equation:

REWARDS – COSTS = CHOICE

When we engage with potential dates and mates, we mentally weigh the pros and cons. For instance, she might think, “He’s tall, confident, funny, and friends with my friends.” But as the conversation progresses, she might add, “But, he chews tobacco, only wants to party, and just flirted with another woman while we were talking.” Throughout our interactions, we assess them based on various factors like appearance, personality, goals, and how we see ourselves in comparison. Rarely do we seek out the most physically attractive person unless we perceive ourselves as equally desirable. Instead, we typically evaluate the overall exchange rationally, aiming to maximize our gains while minimizing our losses.

Furthermore, the evaluation of a potential relationship also heavily depends on factors like racial and ethnic background, religious beliefs, socioeconomic status, and age similarities. The process of selecting a partner involves many obvious and subtle processes that you can relate to your own experiences. If you’re single, you can apply these concepts to your own dating and mate selection endeavors.

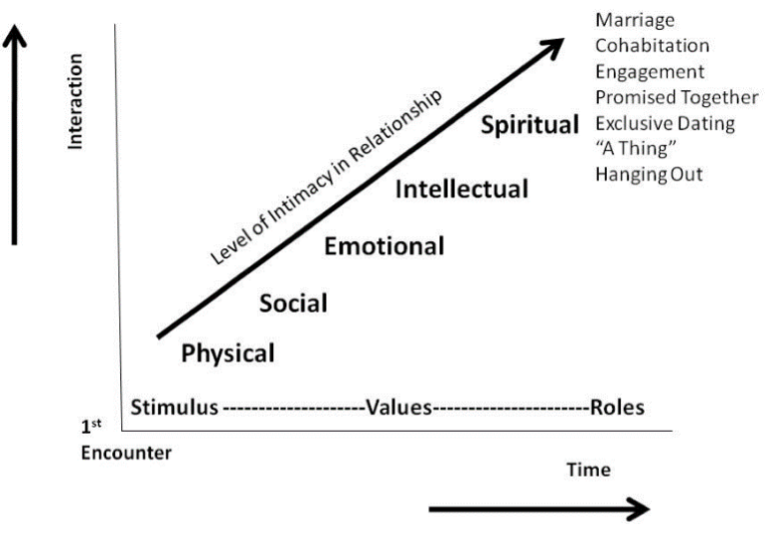

Bernard Murstein explored the stimulus-value-role theory of marital choice in the early 1970s. According to Murstein (1972), the exchange in a relationship is mutual and relies on the subjective attractions and assets each individual brings. The stimulus is the initial trait, usually physical, that draws you to someone. As you spend time together, you compare values to assess compatibility and calculate the balance between maximizing rewards and minimizing costs. If compatibility and relational support align, the couple may progress to assuming roles such as boyfriend, girlfriend, husband, or wife, which may include exclusive dating, cohabitation, engagement, or marriage. The figure below illustrates how the stimulus-values-role theory overlaps with a couple’s development of intimacy through increased time and interaction.

But how do strangers move from not knowing each other to living together or getting married? From the first encounter, two strangers embark on a process that either excludes or includes each other as potential partners and begins establishing intimacy. Intimacy involves a mutual sense of acceptance, trust, and connection, despite acknowledging each other’s imperfections. In essence, intimacy is about becoming close to one another, accepting each other as is, and feeling accepted by the other. It’s important to note that intimacy isn’t limited to sexual intercourse although it may be one expression of it. When two strangers meet, there’s a stimulus that catches one or both parties’ attention.

In Judith Wallerstein’s book, there’s a story about a woman who, while on a date, heard another man laugh in a way that reminded her of Santa Claus. Wallerstein (2019) asked her date to introduce her, and that marked the beginning of a relationship that eventually led to her marrying the man with the distinctive laugh. Many people share stories of feeling a subtle connection, like reuniting with a long-lost friend, when they first meet someone they click with.

The process of forming a connection starts with a stimulus, which could be physical, social, emotional, intellectual, or spiritual, sparking interest and initiating interaction. As time passes and interaction increases, two individuals may compare and contrast their values, which ultimately determines whether they include or exclude each other from their lives. The more time spent together, coupled with growing trust and self-acceptance, the greater the intimacy and likelihood of a long-term relationship.

Although Figure 2.2 suggests that intimacy typically increases smoothly over time, this isn’t always the case. As a couple develops a bond, they establish patterns of commitment and loyalty, leading to the roles listed in Figure 2.2. These roles increase in commitment level but don’t follow a predictable sequence. For instance, some couples may stick to exclusive dating, the mutual agreement to exclude others from dating either individual in the relationship, while others may progress to cohabitation or marriage.

Figure 2.2 Stimulus-values-role theory

Source: Hammond, Ron, Paul Cheney, Raewyn Pearsey. 2021. Sociology of the Family. Ron J. Hammond & Paul W. Cheney. Retrieved May 7, 2024 (https://freesociologybooks.com/Sociology_Of_The_Family/08_Dating_and_Mate_Selection.php).

Source: Hammond, Ron, Paul Cheney, Raewyn Pearsey. 2021. Sociology of the Family. Ron J. Hammond & Paul W. Cheney. Retrieved May 7, 2024 (https://freesociologybooks.com/Sociology_Of_The_Family/08_Dating_and_Mate_Selection.php).

It’s worth noting that what you look for in a date may differ from what you seek in a spouse. Dates are temporary adventures where factors like physical attraction, personality, entertainment value, and social status matter. Dates can be short-term or consist of a few outings. Many college students develop relationships that are noticed by themselves and their peers but lack a defined destination until they have a DTR, or “Define the Relationship” talk, where they openly discuss their goals for the relationship, such as exclusive dating or ending it.

Have you ever experienced a DTR? Many find them awkward due to the stakes involved. DTRs can be risky because they require vulnerability and self-disclosure. In the TV show The Office, Jim and Pam navigate several DTRs early in their relationship, reflecting on the challenges many couples face in real life.

Jim and Pam’s story also highlights the importance of cultural similarities in relationships. Despite coming from the same region and sharing many social and cultural traits, their relationship faced hurdles. Cultural and ethnic background traits influence inclusion and exclusion decisions in relationships, with the similarity principle playing a key role. This principle suggests that perceived similarities between individuals increase the likelihood of relationship success, with individuals often prioritizing certain background traits over others based on personal preferences and beliefs.

In the movie My Big Fat Greek Wedding, the main character, a Greek American woman, meets a charming man from a different ethnic background. She struggles with including him as a potential partner due to her perception that her cultural and family background might not be desirable to others. However, he finds her family deeply appealing because they fulfill his need for connection, tradition, and support. He embraces the Greek culture and adopts her family as his own.

In reality, most people don’t make such significant compromises when choosing a partner. Relationships are more likely to develop when there are common traits, particularly in areas that individuals consider important. Dating often leads to exclusive relationships, allowing young adults to gain experience in intimate relationships and daily routines together. While not all dating relationships evolve into long-term commitments, the experience gained is invaluable compared to the pain of a breakup.

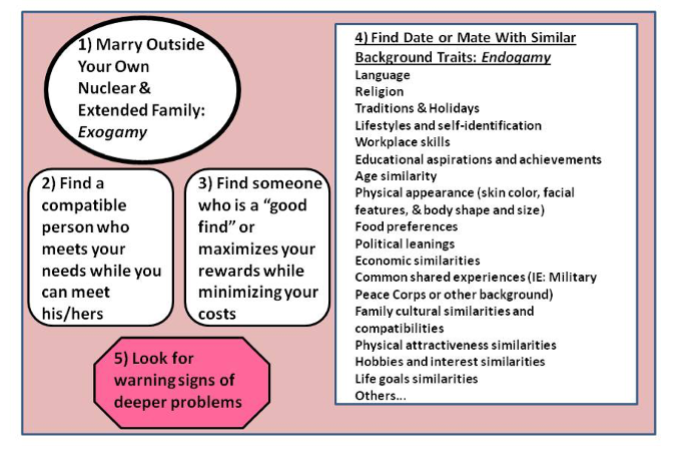

Figure 2.3. summarizes several rules that can guide how we include potential partners in our dating pool. Rule #1 is exogamy, which involves pairing off or marrying someone outside of your own familial groups. Rule #4 emphasizes maximizing homogamy by seeking commonalities that ease daily adjustments in the relationship. While finding a perfect match on all traits is unlikely, compatibility in personality and background characteristics is crucial. Rule #5 is particularly important as it involves identifying trouble and danger signs in a potential partner. Intimate violence is a serious concern, especially for women, and early warning signs should not be ignored.

Figure 2.3 Dating & Mate Selection Rules

Source: Hammond, Ron, Paul Cheney, Raewyn Pearsey. 2021. Sociology of the Family. Ron J. Hammond & Paul W. Cheney. Retrieved May 7, 2024 (https://freesociologybooks.com/Sociology_Of_The_Family/08_Dating_and_Mate_Selection.php).

Source: Hammond, Ron, Paul Cheney, Raewyn Pearsey. 2021. Sociology of the Family. Ron J. Hammond & Paul W. Cheney. Retrieved May 7, 2024 (https://freesociologybooks.com/Sociology_Of_The_Family/08_Dating_and_Mate_Selection.php).

Most people don’t encounter extreme dangers while dating, but emotional risks are common. Engagements often occur more frequently in warmer months, leading to the initiation of various social experiences as couples announce their plans to family and friends. Engagement announcements mark the exclusion of other potential suitors as the couple transitions into exclusive monogamy. The engagement ring symbolizes the agreement to marry, with its cost varying widely. Wedding plans are formalized through newspaper announcements, mailed invitations, or online posts. In-laws become part of the family network upon marriage, though relationships with them may not always be smooth sailing. There’s a recent article by Jennifer Bernstein (2019) titled “What does an engagement ring actually signify?” that’s definitely worth checking out.

Establishing connections with extended family members is essential for a successful engagement. In-law relationships are expected to be at least somewhat compatible with the new family member (the fiancé), ideally leading to close bonds. Engagement signifies the couple’s commitment to the direction of their relationship, ultimately leading to marriage and the blending of social networks, possessions, finances, intimacy, rights, children, and other aspects. It offers opportunities for the couple to practice various aspects of married life. While most engagements culminate in marriage, some end in breakups where the wedding is called off. Couples may realize they aren’t as compatible as they initially thought, face geographical separation, encounter conflicts with in-laws, or simply drift apart.

Finding a spouse can be challenging due to what social scientists term a marriage squeeze in the United States—a demographic imbalance in the number of eligible males and females. Additionally, there’s the phenomenon of the marriage gradient, where women tend to marry slightly older and taller men, while men tend to marry women perceived as slightly more attractive. According to the U.S. Census, there are approximately 15,675,000 males and 15,037,000 females aged 18 to 24, leaving a surplus of 638,000 males in the marriage market within this age group (Walker et al. 2023). This surplus contributes to a “marriage squeeze” because women generally prefer to marry men who are slightly older, resulting in an imbalance where there are too few females for all available males.

China and India face significant challenges related to their marriage squeeze issues. Sex-selective abortion, cultural preferences for males, female infanticide, and societal views that consider female children burdensome rather than sources of joy have led to tens of millions of missing females in these populations. For example, India had an excess of 35 million men nationwide (Denyer and Gowen 2018). Similarly, China was reported to have approximately 35 million more men than women (Denyer and Gowen 2018).

ANALYZING FAMILY STRUCTURES

The Cost of Singlehood

Read the article, “The Cost of Singlehood,” from The Atlantic.

Respond to the article with the following:

- Summarize the main idea and conclusion the authors conveyed.

- What was your reaction or feelings about the reading?

- What is the most important idea or concept presented as it relates to the economic and social impact of remaining single?

“The Cost of Singlehood” by Katie Conklin, Lemoore College is licensed under CC BY 4.0