3.4 Sexuality

Sexuality holds significance for us because it marks a transition into adulthood, offers pleasure, and reinforces gender roles and aspirations. However, despite its importance, sexuality is a relatively passive aspect of our daily lives. In 1993, Samuel and Cynthia Janus (1993) conducted The Janus Report on Sexual Behavior, studying 2,765 men and women to uncover general trends in U.S. sexual practices. They found that sexual frequency is quite similar across age groups, with most individuals engaging in 2-3 sexual encounters per week.

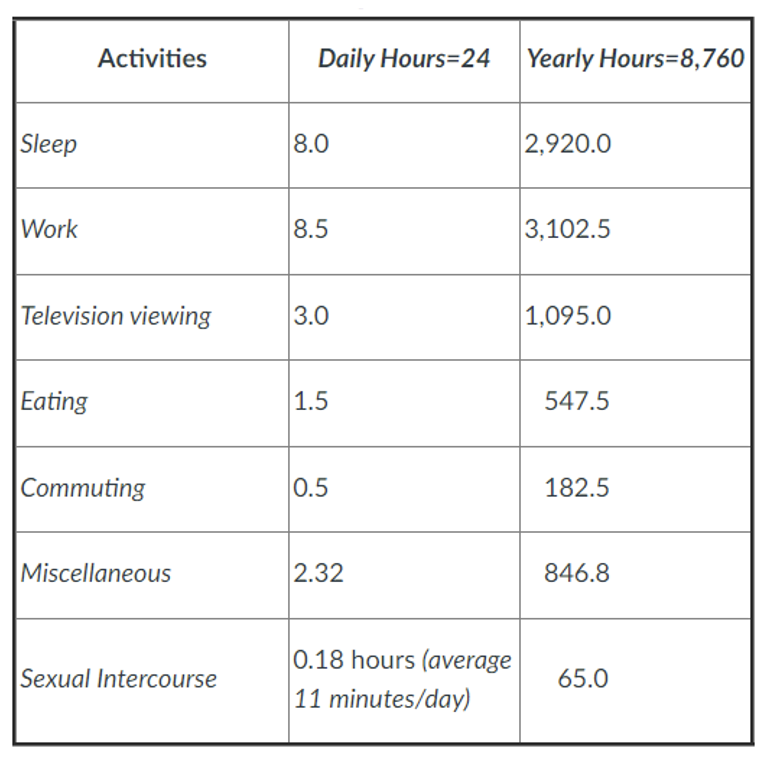

On average, individuals with a sexual partner engage in sex about three times a week, with each session lasting around 25 minutes. This amounts to approximately 75 minutes per week or 65 hours per year spent on sexual activity. While this might seem like a significant portion of time, it pales in comparison to other daily activities.

Consider the following breakdown: assuming the average person sleeps for eight hours, works for 8.5 hours, eats for 1.5 hours, commutes for 0.5 hours, watches TV for three hours, and engages in miscellaneous activities for 2.5 hours daily, sexual intercourse comprises a relatively small portion of our time (Janus and Janus 1993).

Table 3.1. Daily and Yearly Hours Spent in Various Activities for an Average Person

Source: Hammond, Ron, Paul Cheney, Raewyn Pearsey. 2021. Sociology of the Family. Ron J. Hammond & Paul W. Cheney. Retrieved May 3, 2024 (https://freesociologybooks.com/Sociology_Of_The_Family/07_Sexual_Scripts.php).

Source: Hammond, Ron, Paul Cheney, Raewyn Pearsey. 2021. Sociology of the Family. Ron J. Hammond & Paul W. Cheney. Retrieved May 3, 2024 (https://freesociologybooks.com/Sociology_Of_The_Family/07_Sexual_Scripts.php).

Sexual intercourse plays a passive role in the lives of most individuals, accounting for only 65 hours per year on average. Many people abstain from regular sexual activity until their twenties, and those who are unmarried are less likely to engage in it compared to married individuals. Additionally, these estimations do not include individuals without sexual partners or those who abstain from intercourse, which would further lower the average involvement in sexual activity.

Indiana University is renowned for conducting the largest sex-focused survey in the United States, known as the National Survey of Sexual Health and Behavior (NSSHB). The survey’s initial phase was done in 2009, gathering data from over 20,000 participants aged 14 to 102. This extensive study has resulted in more than 30 research publications, exploring various aspects of sexual behavior (NSSHB 2024).

The survey delves into diverse sex-related topics, including condom usage, intimate behaviors like kissing and cuddling in relation to sexual arousal and intimacy, patterns of sexual behavior across different sexual orientations and identities, knowledge about sexually transmitted diseases, and relationship dynamics (NSSHB 2024).

The findings from the first wave of data collection revealed several interesting trends. A majority of U.S. youth were found not to engage in regular intercourse, and condom use was not commonly associated with reduced sexual pleasure among adults. Men were more likely to experience orgasm during vaginal intercourse, while women’s orgasm experiences were more varied, often influenced by factors like oral sex (NSSHB 2024).

Despite a relatively small percentage identifying as gay, lesbian, or bisexual, a significant number reported engaging in same-sex behavior at some point. Women were more inclined to identify as bisexual rather than lesbian. Interestingly, there was a discrepancy between men’s perception of their partners’ orgasms and women’s actual reported experiences. Older adults were found to maintain active sex lives, with the lowest rate of condom use observed among those over 40 (NSSHB 2024).

Subsequent waves of data revealed further insights. Women were generally more accepting of individuals identifying as bisexual compared to men. Most participants reported being in monogamous relationships, but same-gender sexually oriented individuals were less likely than their opposite-gender counterparts to report monogamy (NSSHB 2024).

Sexual Orientation

Sexual orientation refers to the part of a person’s identity that involves being attracted to another individual, whether in a sexual, emotional, physical, or romantic sense. Traditionally, sexual orientation has been viewed as binary, either heterosexual (attraction to the opposite sex/gender) or homosexual (attraction to the same sex/gender). However, recent advancements in sexuality research have led to discussions about orientation occurring on a continuum, encompassing a variety of orientations (Killerman 2020).

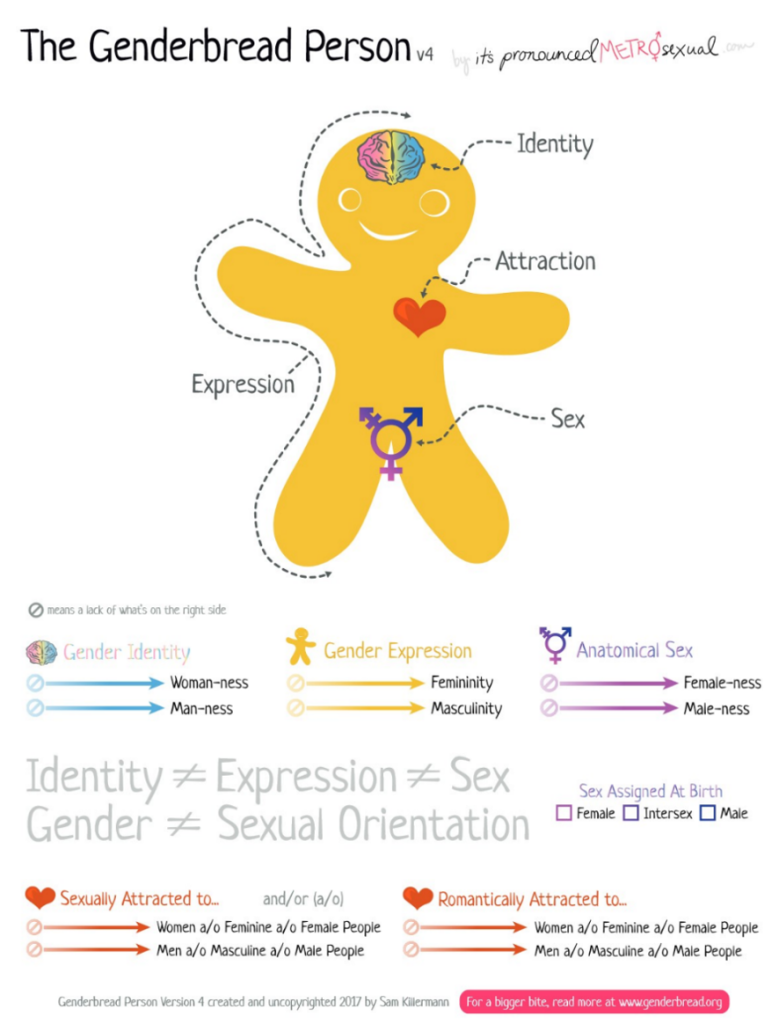

Before examining into the broader spectrum of orientations, it’s essential to understand the Genderbread Person concept in Figure 3.2 (Killerman 2020). This framework helps us comprehend orientation along a continuum, considering factors like birth sex, anatomical sex, gender identity, gender expression, sexual attraction, and romantic attraction.

We are all born with a biological sex, but one’s current anatomical sex may differ from their birth sex, especially for individuals who have undergone sexual reassignment surgery (Killerman 2020). Gender identity pertains to how we perceive ourselves and may not necessarily align with our anatomical sex or gender expression. For instance, one may be biologically female but identify as male or have a fluid gender identity.

Gender expression refers to how we present ourselves in terms of adhering to gender norms. This can range from extremely masculine or feminine to androgynous, with expressions changing over time and in different contexts (Killerman 2020).

Attraction comes in two forms: sexual and romantic. These can vary independently, meaning one may be romantically attracted to individuals of one gender but sexually attracted to another. Sexual attraction involves arousal and desire for sexual intimacy, while romantic attraction relates to emotional connections (Killerman 2020).

Figure 3.2 The Genderbread Person

Source: Killerman, Sam. 2020. “The Genderbread Person v3.3.” It’s Pronounced Metrosexual. Retrieved May 8, 2024 (https://www.itspronouncedmetrosexual.com/2015/03/the-genderbread-person-v3/).

Asexuality refers to a sexual orientation where individuals lack sexual attraction to others, but it’s important to note that it’s not considered a disorder. Despite being one of the least studied orientations, there’s ongoing debate about whether asexuality represents a lack of orientation or is an orientation. Only a small percentage, around 0.5-1% of the population, identifies as asexual, with potential underestimations. Those identifying as asexual are mostly white (Deutsch 2017).

Being asexual doesn’t necessarily mean abstaining from sexual behavior or intercourse, nor is it defined by virginity, low sex drive, or lack of masturbation. Asexual individuals may experience physical arousal, though some may feel disconnected from it, a phenomenon known as auto-crissexualism (Deutsch 2017). Asexuality manifests in various forms, such as gray asexuality, where individuals experience low levels of attraction, and demisexuality, where sexual attraction only occurs after forming a close bond. Importantly, an asexual person may still experience romantic attraction to any gender (Deutsch 2017).

Heterosexuality denotes attraction to the opposite gender and is the most common orientation. Cultural norms historically centered around heterosexuality as the norm, marginalizing other orientations. Though efforts have been made to challenge this mindset, its influence persists (Gates 2011).

Same-gender sexuality, or homosexuality, involves being sexually attracted to individuals of the same gender. Around 3.5% of the U.S. population identifies as having same-gender attractions, with rates higher among women. While fewer individuals identify as homosexual, a significant portion report attraction to the same gender or engaging in same-gender sexual behavior (Copen et al. 2016).

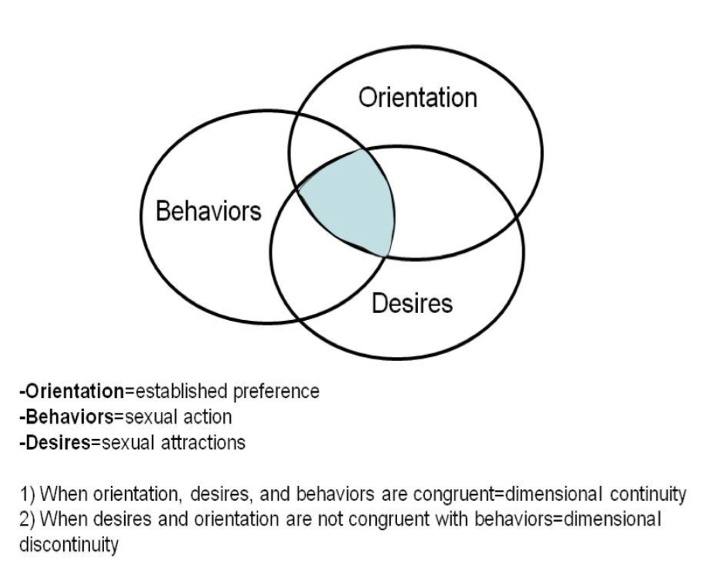

Sexual fluidity challenges binary views of sexuality by acknowledging that attraction can be fluid. Bisexual individuals are attracted to both same and opposite genders, whereas pansexual individuals are attracted to all genders, not limited to a binary framework (Rice 2015). Visual aids like Figure 3.3 help illustrate how sexual orientation, desires, and behaviors can align or diverge. Surprisingly, these dimensions of sexuality often don’t align among adults in U.S. society (Rice 2015).

Figure 3.3 Sexual Orientation, Desires, and Behaviors

Source: Rice, Kim. 2015. “Pansexuality.” In The International Encyclopedia of Human Sexuality (eds A. Bolin and P. Whelehan). https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118896877.wbiehs328

Edward O. Laumann and his team (1994) conducted the most extensive sociological study on U.S. sexuality to date. In their research, they explored the prevalence of self-identified sexual orientations, surveying approximately 3,400 participants. Many individuals in U.S. society identify as heterosexual, although Laumann opted not to use the terms “heterosexual” or “homosexual.” They found that a small percentage of both males and females had engaged in sexual activity with a partner of the same sex (Laumann et al. 1994).

Laumann’s (1994) study also revealed that over 96% of males and 98% of females identified as heterosexual. A very small percentage identified as homosexual, while slightly more identified as bisexual. The Janus Report (1993), another significant study, also examined sexual behaviors and orientations. Their findings indicated that a notable proportion of men and women reported having had a homosexual experience.

According to Janus, many men and women identified as heterosexual, with a small percentage identifying as homosexual or bisexual. Heterosexuality consistently emerges as the most common identification when individuals are asked about their sexual orientation (Janus and Janus 1993).

However, individuals who identify as heterosexual may still have diverse sexual experiences yet maintain their heterosexual identity. Despite variations in sexual experiences, the U.S. is characterized as a nation with a high level of sexual activity. Many men and women reported having had vaginal intercourse, with men typically initiating sexual activity earlier than women. Only a small percentage of individuals reported no sexual experience before marriage (Janus and Janus 1993).

ANALYZING FAMILY STRUCTURES

Is it Love or Lust?

How do you know whether the passion and butterflies in your stomach are signs of romantic love or simply lust? In the video, Is it love or lust?, Dr. Orbuch will discuss signals to distinguish between lust and love, and how to reignite that lustful desire in loving long-term relationships.

Consider the following questions in your response:

Dr. Orbuch is a professor of sociology, and has been referred to as the “Doctor of Love” by some news media outlets. Consider her area of research. What sociological theory underlies her perspectives on love? What signs distinguish lust from love, according to Dr. Orbuch?

“Is It Love Or Lust?” by Katie Conklin, Lemoore College is licensed under CC BY 4.0