1.5 Theoretical Views on the Family

The average person’s daily life is too limited to fully grasp the complexities of today’s social world. We spend our time with friends and family, at work, engaging in leisure activities, and consuming media like TV and the internet. With so much going on in our own small spheres, it’s impossible to comprehend the broader picture of a society with hundreds of millions of people. There are countless communities, millions of interactions between individuals, billions of online sources of information, and numerous trends unfolding without many of us even being aware of them. How can we begin to make sense of this vast and intricate social landscape?

Sociological Imagination

- Wright Mills, a sociologist from the mid-20th century, proposed that when studying families, we can gain valuable insights by considering them within two core societal levels. He argued that understanding both the individual experiences (or “troubles”) and the broader social issues they’re part of is essential. Mills famously stated, “neither the life of an individual nor the history of a society can be understood without understanding both” (Mills 1959:ii). By recognizing both personal challenges and larger social issues, we can begin to uncover the hidden social processes shaping today’s societies.

Personal troubles are individual challenges that arise within a person’s own life and immediate relationships. According to Mills (1959), we play the role of actors and actresses in our personal lives, making decisions about our friendships, family, work, school, and other aspects within our control. We have some level of influence over these personal matters. For instance, a college student who frequently parties, skips classes, and neglects homework faces personal troubles that hinder their chances of success in college. However, when these issues become widespread and affect a significant portion of the population, they are termed larger social issues. For example, when half of all college students nationwide fail to graduate, it becomes a broader social concern.

On the other hand, social issues extend beyond individual control and personal spheres, involving society’s organization and processes. To better understand these issues, we must consider social facts, which are social processes inherent to society rather than individual experiences. Émile Durkheim (1982), a French sociologist, explored the concept of social facts as part of his study of the “science of social facts,” aiming to identify social correlations and laws to comprehend the workings of modern, diverse, and complex societies (p. 50-59).

Several significant social phenomena shape our world today, including conflicts like the war in the Middle East, economic challenges, fluctuations in gas prices, imbalances in the dating market, and the rising demand for plastic surgery. These are what we refer to as social facts, which are aspects of society that exist outside the control of individual people. While they affect us, we often struggle to influence them in return. As Mills highlighted, much of our lives unfold at the personal level, while many societal issues operate at a larger social level. Without understanding both personal experiences and broader social dynamics, we remain unaware of the full scope of social realities, which Mills (1959) termed as false social consciousness.

One example of a larger social issue is the nationwide trend of college freshmen arriving ill-prepared for the demands of college life. Many of them haven’t faced sufficient challenges in high school to develop the skills needed to succeed in college. Across the country, teenagers spend their time texting, browsing the internet, playing video games, socializing with friends, and working part-time jobs. With such distractions, it’s difficult for them to gain the focus and self-discipline required for college-level studies, including completing assignments, participating in group work, and preparing for exams.

The true strength of the sociological imagination lies in our ability to differentiate between the personal and social aspects of our lives. By understanding this distinction, we can make decisions that benefit us most, considering the broader social influences we encounter.

ANALYZING FAMILY STRUCTURES

Using Your Sociological Imagination

Describe and employ your sociological imagination to evaluate family.

Examine your personal family. Discuss at least three of the following, using the subheadings:

- Love

- Mate selection

- Sexuality

- Communication patterns

- Parenthood

- Divorce

How do your life experiences influence how you view family as a social institution?

What agents of socialization have impacted your vision of family and relationships?

“Using Your Sociological Imagination” by Katie Conklin, Lemoore College is licensed under CC BY 4.0

Historical Influences

In today’s United States, the family is profoundly influenced by a key factor that operates at both the broader societal and individual levels: demography. Demography, the scientific study of population growth and change, encompasses all aspects of society and, in turn, is influenced by them.

Following World War II, the United States underwent a period of recovery from the war’s profound and lasting impacts. Families had endured separations, loss of relatives, injuries, and shifts in women’s roles, with many returning from wartime factory work to their homes. This upheaval was reflected in the demographic trends of the time, particularly in the year 1946, which saw significant deviations from typical demographic patterns. During this period, people married at younger ages, had more children per woman, experienced higher rates of divorce and remarriage, and tended to have larger families. This trend, known as the Baby Boom, lasted from 1946 to 1964 and resulted in a significant increase in the birth rate, peaking before gradually declining to pre-1946 levels by 1964. The generation born during this period, the Baby Boomers, numbering approximately 78 million today, had a profound impact on both personal and societal levels due to their sheer numbers and the unique circumstances of their upbringing.

The influence of the Baby Boomers continues to shape U.S. society, particularly in familial dynamics. The earliest cohort of Baby Boomers holds the record for the highest divorce rates, and collectively, Baby Boomers continue to divorce at higher rates compared to previous generations. Their offspring, including Generations X and Y, also experience unique demographic patterns due to the large size of the Baby Boomer generation.

Understanding demographic processes is essential for comprehending the dynamics of U.S. families, with a focus on three key components: births, deaths, and migration. Demography can be simplified into a basic formula:

(Births – Deaths) +/- ((In-Migration) – (Out-Migration)) = Population Change

The natural increase, comprising births minus deaths, and net migration, encompassing in-migration minus out-migration, are fundamental aspects of demographic analysis.

The Industrial Revolution triggered significant demographic shifts in the United States, leading to increased birth rates and decreased mortality rates, which had far-reaching implications for society and family structures (Hammond et al. 2021).

Before the Industrial Revolution, families primarily lived on small farms where everyone in the family worked to support the family economy. Towns were small and similar, and families tended to be large since more children meant more workers. Living standards were lower, and life expectancy was shorter due to poor sanitation. However, with the onset of the Industrial Revolution, factory work replaced farm work, leading men to become breadwinners outside the home. This resulted in the purchasing of goods that were previously handmade or traded. Women took on the role of managing household tasks, overseeing homework, and often worked both at home and in factories. As a result, cities grew larger and more diverse, and families became smaller as less farm work required fewer children. Over time, living standards improved, and mortality rates decreased.

It’s crucial to recognize the significant role of women’s work both before and after the Industrial Revolution. Women have historically performed extensive unpaid labor, such as homemaking. The changes brought about by the Industrial Revolution impacted Western civilization, affecting countries like Western Europe, the United States, Canada, Japan, and Australia similarly. However, alongside the benefits, the Industrial Revolution also introduced social challenges, including poor living conditions, overcrowding, poverty, inadequate sanitation, early mortality, and family pressures. Today, sociology continues to address these complex social issues, particularly within the family context.

Table 1.2 Pre-Industrial & Post-Industrial Revolution Social Patterns

| Pre-Industrial Revolution | Post-Industrial Revolution |

| Farms and cottages | Factories |

| Family work | Breadwinners and homemakers |

| Small towns | Large cities |

| Large families | Small families |

| Homogeneous towns | Heterogeneous cities |

| Lower standards of living | Higher standards of living |

| People died younger | People die older |

Source: Hammond, Ron, Paul Cheney, Raewyn Pearsey. 2021. Sociology of the Family. Ron J. Hammond & Paul W. Cheney. Retrieved May 3, 2024 (https://freesociologybooks.com/Sociology_Of_The_Family/01_Changes_and_Definitions.php).

Sociological Theories

Sociological theories form the cornerstone of the discipline, offering essential guidance to both researchers and practitioners. They equip us with fundamental tools to understand the complexities of society and how its various components interact. Think of theories like a pair of binoculars; just as binoculars magnify and clarify our view of distant objects, theories magnify and illuminate our understanding of society. While you can’t physically touch or see a theory, it serves as a conceptual framework to help us perceive the social world more clearly.

Imagine different social phenomena as objects viewed through different lenses of binoculars. Each theoretical perspective offers a unique vantage point, allowing us to examine society from different angles and uncover diverse insights. Whether we’re analyzing social conflicts, functions, or interactions, theories provide us with distinct perspectives to explore the complexities of social life.

Theories are collections of interconnected concepts and ideas that have undergone scientific scrutiny and synthesis to deepen our comprehension of individuals, their actions, and the societies they inhabit. They serve as guiding frameworks for sociological inquiries, directing researchers to conduct specific types of studies and formulate questions that can evaluate the theory’s premises. Once a study is conducted, its findings and overarching patterns are assessed to determine whether they align with the theory. If the results corroborate the theory, subsequent studies may replicate and refine the process. Conversely, if the findings diverge from the theory, sociologists reassess and revisit the assumptions underlying their research.

Theories play a vital role in examining society, whether it encompasses millions of individuals within a state, country, or globally. When applied to the study of vast populations, these theories are known as macro theories, which are best suited for analyzing large-scale social dynamics (i.e., conflict theory, feminism, functionalism, family systems theory). Conversely, when theories are employed to scrutinize small groups or individuals, such as couples, families, or teams, they are classified as micro theories, which are tailored for investigating interpersonal interactions within smaller social units (i.e., symbolic interactionism, family developmental theory, the life course perspective, and social exchange theory). However, each theoretical perspective can be used at both macro and micro levels, known as multi-level of analysis (i.e., ecological theory). Let’s explore each of these major theoretical perspectives separately.

Conflict theory

Conflict theory, classified as a macro theory, is a sociological framework crafted to explore broader social, global, and societal phenomena. This theory originated from the insights of a German philosopher, economist, sociologist, and revolutionary, Karl Marx (1818-1883). Witnessing the oppression inflicted by society’s privileged class upon the impoverished masses, Marx (1893) grew critical of the capitalist principles underlying such unjust exploitation. He viewed conflict as an inherent aspect of all human societies. Subsequently, another German thinker named Max Weber (1864-1920; pronounced “Veybur”) elaborated on and refined this sociological theory, adopting a more nuanced perspective. While Weber (1930) inquired further into the study of capitalism, he diverged from Marx’s outright dismissal of it.

Conflict theory provides valuable insights into many social phenomena, including war, wealth disparity, revolutions, political unrest, exploitation, and various forms of social conflict such as discrimination, domestic violence, and child abuse. At its core, conflict theory posits that society is characterized by ongoing competition and struggle among individuals and groups for limited resources. Marx and Weber, prominent thinkers in sociology, would likely apply conflict theory to analyze contemporary issues like the recent bailouts orchestrated by the U.S. government, which have effectively facilitated the transfer of wealth from the rich to the affluent.

Central to conflict theory is the notion that individuals who possess power continually seek to enhance their wealth at the expense of those who lack such resources. This power struggle predominantly favors the wealthy elite, often resulting in the exploitation and suffering of the less privileged. Power, defined as the ability to achieve one’s objectives despite opposition, is institutionalized through authority, with the bourgeoisie—comprising royalty, political figures, and corporate leaders—exerting considerable influence.

In this dynamic, the bourgeoisie, akin to societal “Goliaths,” wield significant power and frequently impose their preferences on societal outcomes. Conversely, the proletariat—comprising the working class and the economically disadvantaged—find themselves marginalized and oppressed by the bourgeoisie. According to Marx, the inherent conflict between the bourgeoisie and the proletariat necessitates periodic uprisings and revolutions by the latter to challenge the dominance of their oppressors.

Marx and Weber both recognized the existence of distinct social classes and observed a consistent pattern where a small minority holds significant wealth and power, while the majority struggles with poverty. This disparity in wealth often results in the affluent dictating the course of societal affairs. Consider the collection of images below depicting homes in a particular U.S. neighborhood. On the west side of a gully, these homes appear dilapidated, impoverished, and of low value. Their condition can be starkly contrasted with the opulent mansions situated on the east side, causing frustration among residents who must traverse through these “slums” to access their own lavish residences. Visit the Dollar Street website and compare the housing of families living in the United States. Select a house on the website for additional information about the family and their living conditions inside their home.

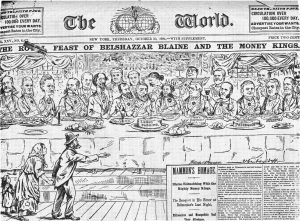

Political cartoon from October 1884, showing wealthy plutocrats feasting at a table while a poor family begs beneath.

Conflict theory has been extensively tested using scientific data, consistently demonstrating its broad applicability across various levels of sociological investigation. However, it’s important to note that not all sociological phenomena adhere strictly to conflict-based principles. Nonetheless, many conflict theorists argue that conflict assumptions frequently hold true. One theoretical perspective heavily rooted in conflict theory is feminism.

Feminism

Feminism is a perspective within sociology that builds upon conflict theory assumptions, but extends its focus to incorporate considerations of sex, gender, sexuality, and other related attributes within the study of society. Feminist theorists often analyze the unequal distribution of power between men and women in both societal and familial contexts. Central to the feminist perspective is the emphasis on choice and the equal valuation of individuals’ choices.

There are four key themes that characterize feminism:

-

- Recognition of women’s oppression

- Examination of the factors that perpetuate this oppression

- Commitment to ending unjust subordination

- Vision of achieving equality in the future

Historically, women’s subordination has been evident in philosophical works such as those of Plato, who espoused the notion of men’s inherent virtue and superior reasoning abilities. The 19th-century Industrial Revolution marked the emergence of the women’s movement, with figures like Elizabeth Cady Stanton establishing organizations like the National Organization for Women (NOW) and Susan B. Anthony advocating for women’s suffrage. The feminist movement gained momentum in the 1960s, coinciding with the Civil Rights Movement, and addressed issues such as equal pay, dissatisfaction among housewives, and the role of power in shaping gender norms.

Feminism encompasses various perspectives, including liberal feminism, social feminism, and radical feminism, each with its own approach to addressing gender inequality. Liberal feminists advocate for social and legal reforms to achieve gender equality, while social feminists focus on redefining capitalism in relation to women’s work. Radical feminists view oppression of women as the most fundamental form of oppression and seek to dismantle patriarchal systems.

Strengths of feminism include their applicability to diverse issues and their critical examination of theories that neglect gender and power dynamics. However, challenges may arise due to the emotionally charged nature of research and practice in this field, as well as potential overemphasis on gender and power dynamics.

Major assumptions underlying feminism include:

-

- Recognition of women’s oppression

- Emphasis on the centrality and significance of women’s experiences

- Understanding gender as a socially constructed concept

- Recognition of the socio-cultural context in analyzing gender dynamics

- Critique of the concept of “family” due to its inherent biases

Feminism has evolved to incorporate the concept of intersectionality, which highlights the interconnectedness of social categories such as race, sexuality, and gender, leading to intersecting forms of discrimination and disadvantage. For example, a Black queer woman may face compounded societal disadvantages compared to a White straight woman, underscoring the importance of considering multiple dimensions of identity.

Functionalism

Functionalism posits that society operates in a state of equilibrium, maintained through the functioning of its various components. Drawing on biological and ecological concepts, this theory likens society to a living organism, with its parts working together to maintain stability. Just as one might analyze the functioning of specific systems within the human body, sociologists study society by examining which societal elements are functioning properly or malfunctioning. They diagnose issues and propose solutions aimed at restoring balance. Examples of functional processes in society include socialization, religious participation, friendships, healthcare, economic recovery, peacekeeping, justice, population dynamics, community cohesion, romantic relationships, and family dynamics, both typical and atypical.

Functionalists and conflict theorists both recognize that society experiences breakdowns and unfair treatment of individuals. These breakdowns, termed dysfunctions, are disruptions in society and its components that endanger social stability. Functionalists distinguish between two types of functions: manifest and latent functions. Manifest functions are the obvious and intended roles of institutions in society, while latent functions are less obvious, unintended, and often unrecognized.

Functionalism, unlike conflict theory, tends to adopt a more positive and optimistic outlook. Functionalists view society as akin to a body that can become “ill” or dysfunctional. By examining society’s components and processes, functionalists seek to understand how society maintains stability or adjusts to destabilizing forces. They argue that most societies achieve a healthy balance and can recover from disruptions, maintaining equilibrium through social processes that counteract destructive forces.

Family systems theory

A crucial concept to grasp when studying families is family systems theory. This theory suggests that families are best understood as intricate, dynamic, and ever-changing systems composed of various parts, subsystems, and individual members. To illustrate, think of a mechanic diagnosing a broken-down car by examining its computer system to identify which components are malfunctioning—like the transmission, electric system, or fuel system. Similarly, therapists or researchers use family systems theory to interact with family members and identify areas within the family system that may need attention or intervention. Family systems theory falls under the functional theory framework and shares its approach of analyzing both the dysfunctions and functions within complex groups and organizations.

To grasp the concept of systems and subsystems, let’s delve into the extended family of Juan and Maria as an illustration. Juan and Maria, a middle-aged couple, reside in a home filled with various family members: Juan’s parents, Maria’s widowed mother, their children Anna and José, Anna’s husband Ming, and their newborn twins. Juan, being financially stable, can support this multigenerational setup, constituting a complex four-generation family system. Within the household, there are three couples: Juan and Maria, Grandpa and Grandma, and Ming and Anna. However, each couple experiences different levels of strain.

In contemporary society, multigenerational family systems, typically involving three generations, are becoming more prevalent, often when adult children and their families move back in with their parents. Juan and Maria raised their children with significant assistance from the grandparents. Maria’s mother, a college graduate, has been especially supportive of José, who is currently a sophomore in college and a member of the basketball team. Meanwhile, Juan’s elderly parents are increasingly reliant on care, particularly his mother, who requires daily assistance from Maria.

Maria shoulders the greatest individual strain within this family system. Both Juan and Maria contend with strains arising from each subsystem and dependent family member. They navigate the presence of in-laws in the household, contribute to the care of elderly relatives, and support their son’s basketball commitments. Yet, the arrival of two newborn babies exacerbates the strain, especially for Maria, as Ming, occupied with medical studies, spends long hours away. Anna, overwhelmed by the demands of caring for the infants, adds to Maria’s responsibilities, making the situation overwhelming.

As the matriarch of the family, Maria is part of multiple subsystems simultaneously, including Daughter-Mother, Daughter-in-law-Father-in-law, Daughter-in-law-Mother-in-law, Spousal, Mother-Son, Mother-Daughter, Mother-in-law-Son-in-law, and Grandmother-grandchildren. However, the existence of numerous subsystems does not inherently imply strain or stress. By viewing the family as a complex system with interconnected and interdependent subsystems, solutions can be sought collectively among its members.

This discussion brings attention to the concept of boundaries. Boundaries represent the emotional, psychological, or physical separations between individuals, roles, and subsystems within the family. Establishing and maintaining boundaries is essential for promoting healthy family dynamics. Family systems theory offers insights into identifying areas of strain within these systems and proposes strategies to alleviate such strain.

Symbolic interactionism

Interactionism encompasses two main theoretical perspectives: symbolic interactionism and social exchange theory. Symbolic interactionism proposes that society is comprised of ongoing interactions among individuals who share symbols and their meanings. This theory proves highly beneficial for understanding people, enhancing communication, navigating cross-cultural relations, and fostering positive roommate dynamics.

From values and communication to love, social norms, and even significant historical events like the September 11 attacks, symbolic interactionism offers insights into various aspects of society. By recognizing that individuals inherently engage in symbolic interactions, we gain insights into how to persuade others, comprehend diverse viewpoints, and resolve conflicts.

Symbolic interactionism delves into the intricate meanings attached to symbols. Consider words like “love,” “lust,” and “lard”—each symbolizes distinct concepts. Through our understanding of these symbols and their meanings, we discern significant differences between terms like “love” and “lust.” This theory extends to our daily interactions, where greetings like “How’s it going?” often carry symbolic meanings rather than literal inquiries.

Furthermore, symbolic interactionism sheds light on our self-concept formation and understanding of social roles and expectations. One notable concept within this theory is the Thomas Theorem, which asserts that if individuals perceive a situation as real, its consequences are real to them. For instance, the story of a woman who, upon receiving a false HIV diagnosis, acted as though she had AIDS illustrates the impact of perceived reality on behavior.

Symbolic interactionism fosters understanding and empathy in various relationships, such as between newlyweds, roommates, and family members. By appreciating the differing symbols and meanings held by others, we can bridge gaps and find common ground. Rosa Parks’s simple act of defiance, underscored by her statement, “All I was doing was trying to get home from work,” symbolized the beginning of significant social change during the Civil Rights Movement. Symbolic interactionism serves as a powerful tool for comprehending human behavior and societal dynamics, facilitating meaningful connections, and fostering positive social change.

Family developmental theory

Family developmental theory, originating in the 1930s, draws insights from sociologists, demographers, family scientists, and others to elucidate the evolving nature of families and the patterns of change they undergo across the family life cycle. Initially, it focused on delineating stages within this cycle, as outlined by Evelyn Duvall (1988):

-

- Married couples without children

- Childbearing families: From the birth of the first child until the oldest child reaches about 2½ years old.

- Families with pre-school children: The oldest child is approximately 2½ -6 years old.

- Families with schoolchildren: The oldest child is around 6-13 years old.

- Families with teenagers: The oldest child ranges from about 13-20 years old.

- Families as launching centers: Begins when the first child leaves home and continues until the last child departs.

- Middle-age parents: Extends until retirement.

- Aging families: Continues until the death of one spouse.

Over time, theorists observed that many families did not neatly fit into these stages, such as when launched children returned home, sometimes with their own children. Subsequent iterations of the theory shifted focus towards roles and relationships within the family, while still emphasizing developmental tasks—essential responsibilities for family growth at various life stages. Successful adaptation to changing needs and demands is critical for family survival.

The theory posits several key assumptions: individual development is significant, but the collective

growth of interacting individuals within the family takes precedence. Developmental processes are both inevitable and vital for understanding families, as they progress through similar stages and encounter analogous transition points and tasks.

To comprehend families, it is imperative to consider the tasks and challenges they confront at each stage, assess how effectively they address them, and evaluate their readiness for subsequent stages. However, a notable criticism of this theory is its limited applicability to diverse family forms and its insufficient cultural sensitivity. In today’s context, where myriad family structures exist and are equally valued, there is a growing need for a more inclusive theory that accommodates various life stages and family compositions.

The life course perspective

The life course perspective is important in family sociology and aging. It serves as a framework for understanding age-related transitions as socially constructed and acknowledged by society members. This perspective aids in comprehending how individuals and populations undergo change over time by examining the interplay between individual life stories and broader social structures.

This theoretical framework centers on the timing of events occurring in an individual’s life. For instance, when viewing marriage through a life course lens, it is seen as an ongoing journey intertwined with other life events. Five key themes characterize the life course perspective:

-

- Multiple time clocks: This refers to various events impacting an individual, including personal, family-related, and societal occurrences. Recognizing the interaction among these time frames is crucial, as historical events, like wars or economic downturns, can influence individual life trajectories.

- Social context of development: The perspective emphasizes the role of an individual’s position within the broader social structure, considering factors such as race, class, and sexuality. It also explores the social construction of meanings, cultural contexts, and the interplay between different levels of social development.

- Dynamic view of process and change: It focuses on the interplay between continuity (stability) and change in human development, considering age, period, and cohort effects. This perspective allows researchers to disentangle the effects of these factors to understand family dynamics more accurately.

- Heterogeneity in structures and processes: Acknowledging diversity across family patterns, this theme highlights the wide range of experiences within families.

- Multidisciplinary view: Development is viewed as biological, psychological, and social, necessitating a multidisciplinary approach to understanding human development.

The life course perspective differs from traditional developmental theory, which often prescribes a normative sequence of life stages and overlooks the diversity of family forms. Instead, the life course perspective recognizes the variability in life events and acknowledges the impact of social and historical events on an individual’s life trajectory. It views marriage as the convergence of two distinct life histories shaped by past social events and influenced by future ones.

Social exchange theory

The other interactionist theory, social exchange theory, posits that society comprises ongoing interactions where individuals seek to maximize benefits while minimizing costs. While sharing some assumptions with conflict theory, social exchange theory is rooted in interactionist principles. Essentially, humans are viewed as rational decision-makers capable of making informed choices by weighing the pros and cons of each option. This theory employs a simple formula to gauge decision-making processes:

REWARDS – COSTS = CHOICE

In other words, individuals assess the available options to determine how to optimize rewards and minimize losses. Sometimes decisions lead to favorable outcomes, while other times they result in poor choices. A key concept in this theory is equity, which refers to a sense of fairness in interactions for both oneself and others involved. For instance, disparities in household chores and childcare between couples with both partners working full-time often stem from perceptions of fairness or equity.

Each person continuously evaluates the pros and cons of choices to maximize outcomes. An illustrative challenge posed to students involves going on a date with someone deemed unattractive, covering all expenses, and ending with a brief kiss. This exercise prompts students to question why they would engage in such behavior, thereby deepening their understanding of social exchange theory.

People rely on each other in relationships where they exchange goods, services, or emotions. What’s valued by each person depends on what they get in return from the other. These exchanges can be one-sided, where one person gives without receiving, or reciprocal, where both give and receive.

When making decisions, individuals often consider their partner’s past choices. They also think about what they expect to gain or lose in the future. In imbalanced relationships, the less dependent person usually holds more power. For instance, someone without a college education or a stable job may depend heavily on their partner who earns the household income.

These exchange relationships aren’t just one-time transactions; they happen over time. For a relationship to continue, each person must see more value in staying than in leaving. For example, as long as a married couple sees more value in their relationship than in divorce, they’ll stay together. Sometimes, though, people stay in difficult relationships because they see even fewer desirable alternatives or fear punishment from their partner.

Social exchange theory recognizes that people don’t always act rationally, but it assumes that their actions follow certain patterns. Ultimately, it’s up to each individual, not sociologists, to decide what they value most in a relationship.

Ecological theory

One theory used by sociologists and child development specialists to understand how society shapes individuals and families is Urie Bronfenbrenner’s ecological theory (1974). This theory places the individual at the center and examines various contexts or settings that surround them. These contexts include family, peers, education systems, communities, cultural beliefs, religion, politics, and the economy.

The major assumptions of ecological theory are as follows:

-

- Humans depend on the environment.

- The entire system and its components rely on each other and operate in connection.

- Changes in any part of the system impact the whole system and other parts.

- All humans depend on the world’s resources.

- Family plays a primary role in human development.

- Families interact with multiple environments.

- Interactions are governed by both natural laws and human-made rules.

The microsystem refers to the immediate social environments where an individual interacts face-to-face. These include family, school, work, church, and peer groups. The mesosystem connects two microsystems, either directly or indirectly. For instance, if a child like 10-year-old La’Shawn is at the center of the model, her family represents one microsystem, while her classroom at school represents another. The interaction between these two, such as during a parent-teacher conference, forms part of her mesosystem.

Moving outward, the exosystem comprises settings where the individual isn’t directly involved but significant decisions affect those who do interact with them. Examples for a child might include neighborhood and community structures or their parents’ work environment. The macrosystem acts as the blueprint for organizing the institutional life of society, encompassing broad patterns of culture, politics, economy, and other large social structures. Lastly, the chronosystem reflects changes or consistencies over time in both the individual’s characteristics and their environment. This can include shifts in family structure, socio-economic status (SES), place of residence, societal attitudes towards divorce, and cultural and historical changes.

For example, when applying Ecological Theory to a child of divorce, one would consider how their family dynamics have shifted (microsystem), how changes in parental involvement may affect their schooling (mesosystem), how their parent’s work situation impacts them (exosystem), societal attitudes towards divorce (macrosystem), and how their SES and living situation may have changed over time (chronosystem). Investigating these areas helps Ecological Theorists understand the child’s experiences and challenges.

Theoretical applications

Each of the sociological theories can be applied to examine individual and collective behaviors, but some may offer more insight than others based on how well their assumptions align with the specific issue being studied. For example, conflict theory can be used to explore divorce by examining how conflicts arise and escalate, sometimes resulting in violent disputes. On the other hand, functionalism can shed light on divorce as a mechanism for resolving unsustainable social situations, aiming to restore equilibrium within families or communities.

Symbolic interactionism offers a perspective on divorce that focuses on how individuals define their roles before, during, and after the marriage’s dissolution, and how they navigate new identities as single adults. Meanwhile, social exchange theory can provide insights into the decision-making processes involved in divorce, including the negotiation of asset distribution, child custody arrangements, and the legal transition to single status.

For further reading, Levinger and Moles’ book “Divorce and Separation: Context, Causes, and Consequences” (1979) examines the various factors contributing to divorce and its broader implications.