2.1 Sex & Gender

To understand the dynamics of dating and mate selection, we must first explore the concepts of sex and gender. While often used interchangeably, they refer to distinct aspects. Sex pertains to one’s biological classification as male or female, determined at conception when an X or Y chromosome-carrying sperm fertilizes an egg, resulting in either XX (female) or XY (male) chromosomes (Young 2009). The term “sex” emphasizes biological differences, such as hormone production variations.

Biological differences between sexes primarily manifest in reproductive organs, which begin development around nine weeks into gestation in reaction to hormonal levels. Occasionally, hormonal irregularities during this phase can lead to ambiguous external genitalia, termed intersex. Intersex describes various conditions where reproductive or sexual anatomy doesn’t align strictly with “male” or “female” categorizations, reflecting biology’s natural variation.

Despite perceived differences, males and females share many biological traits, including organs, hair, skin, limbs, nervous and endocrine systems, with similarities outweighing disparities. However, societal focus often fixates on physiological distinctions to explain behavioral variations.

Conversely, gender denotes a cultural marker of personal and social identity, distinct from biological sex (Young 2009). Gender starts with sex assignment based on observable genitalia at birth, with sex being inherent and gender learned through socialization. It’s a socially ingrained construct evident in daily interactions and behaviors, encompassing masculinity, femininity, and androgyny. Androgynous behaviors defy strict masculine or feminine categorizations, illustrating the learned nature of gender roles and expressions.

Gender encompasses attitudes, feelings, and behaviors culturally associated with one’s biological sex, with gender-normative behavior aligning with cultural expectations and gender non-conformity diverging from them. Gender expression, including appearance, clothing, and behaviors, may or may not conform to an individual’s gender identity, defined as one’s sense of being masculine, feminine, androgynous, or transgender.

Gender dysphoria occurs when there’s discomfort due to a misalignment between one’s gender identity and assigned sex at birth. Transgender is an umbrella term for those whose gender identity differs from societal norms associated with their birth sex. Gender is shaped through social learning, influenced by various external factors like family, media, and culture.

Western conceptualizations of gender often adhere to a binary model, recognizing masculinity and femininity as dominant categories and reinforcing the idea of fixed gender roles. However, this perspective overlooks the diversity of gender identities, as seen in cultures like some Plains Indian communities where individuals can embody both masculine and feminine traits, challenging Western notions of gender duality.

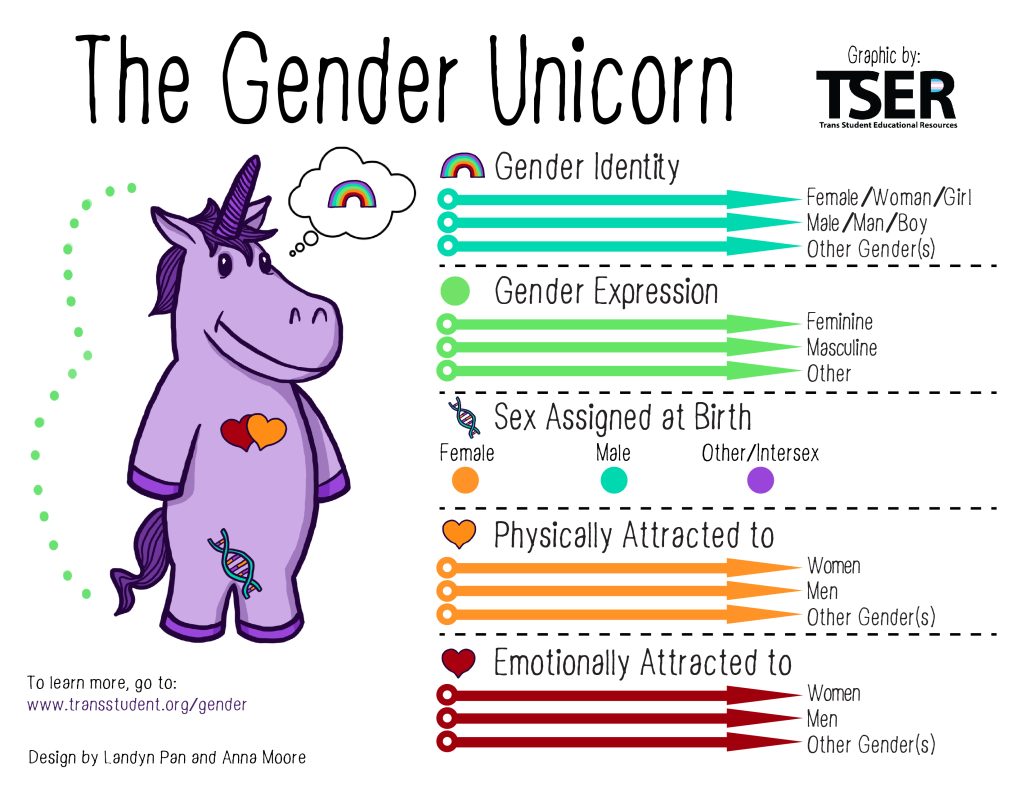

The “Gender Unicorn” in Figure 2.1 illustrates a broader spectrum of elements including sex assigned at birth, gender identity, expression, and attraction, challenging binary categorizations. This graphic emphasizes that while “sex” focuses on biological features, “gender” encompasses fluid and performative characteristics, shaped by social interactions rather than inherent traits.

Figure 2.1 The Gender Unicorn

Male hormones and behavior

Both males and females produce hormones but in varying amounts. Estrogen is predominantly secreted by females, while males produce more testosterone. Studies have suggested a correlation between higher testosterone levels and increased aggressive behavior, primarily observed in animal studies where elevated testosterone levels lead to aggression. However, it’s crucial to note that such findings shouldn’t excuse aggressive behavior with simplistic statements like “Boys will be boys.” This overlooks the role of social influences and individual experiences in shaping behavior.

In human research, higher testosterone levels have been associated with heightened edginess, competitiveness, and anger in both females and males. Moreover, hormone levels fluctuate throughout the day and can be influenced by environmental factors. For instance, consider the contrast between hormone levels before skydiving and while relaxing on the couch watching TV, illustrating the impact of environment on biology. Thus, the notion that testosterone alone dictates men’s behavior has been disproven.

Furthermore, hormones play a role in mood regulation but don’t determine behavior. Despite hormonal influences, individuals can control their actions based on social contexts. For instance, in situations like classrooms or workplaces, individuals may regulate their emotions and behaviors despite feeling aggressive or upset. Behavior is primarily shaped by situational factors rather than hormones alone.

Research also challenges the stereotype that only men exhibit aggression. Women can display similar levels of aggression, especially when incentivized or when social repercussions are minimal. Examples such as athletes like Ronda Rousey and Serena Williams, political figures like Hillary Clinton, and performers like Pink and Chyna demonstrate how women can excel in domains traditionally associated with masculine behaviors. These individuals are not biologically less female but instead challenge societal norms and expectations.

Female hormones and behavior

Women’s hormone levels, especially testosterone, don’t fluctuate as much throughout the day as men’s do. Let me emphasize that again: Women’s hormone levels, particularly testosterone, remain relatively stable throughout the day. Instead, hormonal changes in women are influenced by monthly reproductive cycles and menopause later in life.

Both boys and girls are exposed to negative attitudes toward menstruation from a young age, which can shape women’s perceptions of Premenstrual syndrome (PMS) symptoms. If women are taught to expect PMS to be terrible, they might anticipate it and exhibit behaviors reflecting that expectation. While many women do report mood swings and physical discomfort during this time, research suggests that external stressors can exacerbate these changes. Women might attribute undesirable behavior to PMS, but it’s important to note that hormonal fluctuations don’t determine behavior. It’s a bit like the “Boys will be boys” excuse, isn’t it? In studies involving both men and women, men were just as likely to experience mood swings, work-related issues, and physical discomfort (Hammond and Cheney 2021). Interestingly, men also undergo a daily hormone cycle with testosterone levels peaking around 4 am and lowest around 8 pm.

Gender Socialization

How do we come to understand and perform gender? This process is known as gender socialization, where individual behavior and perceptions are shaped to align with socially defined expectations for males and females. Gender roles, or the expected behaviors and attitudes associated with one’s biological sex, are ingrained in various aspects of society. These include family dynamics, education systems, religious teachings, popular culture, media portrayals, sports, and legal frameworks (Launius and Hassel 2022). Gender roles essentially outline what behaviors are considered acceptable or desirable based on perceived gender.

Gender roles are so deeply ingrained in our daily lives that we often don’t even realize we’re performing them. It’s so ingrained that many people believe gender is innate rather than something we learn and perpetuate through our actions. Essentially, gender is a human creation that only exists when individuals actively engage in it (Zimmerman 1987).

Why do so many people want to know the sex of a fetus before birth? It’s not because knowing affects the baby’s health or happiness or development. It’s often about planning, like decorating the nursery. The color of the nursery might seem trivial, but it reflects deeply ingrained gender expectations. Studies show that a significant majority of parents-to-be want to know the sex of their baby so they can plan accordingly, from nursery decor to toys and even future aspirations (Shipp et al. 2004).

Even before a child is born, parents often have gendered expectations based on the child’s sex. This influences everything from the clothes they buy to the activities they encourage. Gender socialization begins early; parents play a significant role in shaping their child’s understanding of gender. While other factors like peers, media, and religion also contribute, parents wield considerable influence, especially during a child’s formative years.

Adults tend to treat baby girls and boys differently, possibly influenced by their own upbringing and societal gender expectations they experienced as children themselves. For example, in the U.S., it’s often seen that fathers teach boys practical skills like fixing and building, while mothers tend to teach girls domestic tasks like cooking, sewing, and housekeeping (Andersen and Hysock 2009). Sounds a bit old-fashioned, right? Sociologists acknowledge exceptions but note that children still tend to receive more praise from parents when they conform to gender norms and adopt traditional roles, despite changing social attitudes. This reinforcement comes not only from parents but also from other social influences like media and peers, shaping children’s understanding of gender from a young age.

This early socialization leads children to form a gender identity—how they see themselves in terms of being female, male, or neither and develop gender role preferences, aligning with culturally expected behaviors associated with their gender identity (Andersen and Hysock 2009; Diamond 2002).

These childhood gender roles often persist into adulthood, influencing how people perceive decision-making, parenting, financial responsibilities, and even workplace dynamics. It’s important to note that gender roles aren’t inherently good or bad; they simply exist and shape our perceptions of the world around us. Since they’re not biologically determined, they can vary across generations, social groups, and individuals.

Gendered social norms also establish external standards for how females and males should behave, often justified by religious or cultural beliefs. In Western culture, alternatives to traditional gender norms have historically been rare (Foucalt 1972). While there’s no single “correct” way to express gender, individuals are often pressured to conform to societal expectations, reinforcing existing gender norms. Failure to adhere to these norms may lead to individuals being judged based on their character, motives, and predispositions (Zimmerman 1987).

Family

The family, particularly parents or guardians, plays a significant role in shaping a child’s understanding of gender, transmitting their own beliefs about gender to their children both explicitly and implicitly. Research suggests that parents begin to have different expectations for their sons and daughters as early as 24 hours after birth (Rubin et al. 1974). For instance, boys are often perceived as stronger and are treated more roughly and actively engaged with compared to girls from infancy. As children grow, girls tend to receive more protection and less autonomy than boys, and they may face lower expectations in academic and career achievements, especially in areas like mathematics and careers traditionally associated with men (Eccles et al. 1990).

Moreover, many parents consciously or unconsciously steer their sons away from feminine traits. According to Emily Kane, a sociology professor and author, parental efforts to maintain a boundary between masculinity and femininity can limit boys’ options, reinforce gender inequality, and uphold heteronormativity (Kane 2012). These parental messages about gender, tailored to the child’s sex category, are internalized by the child and influence their development into adolescence and adulthood. As a result, gender role stereotypes are often firmly established in childhood (Arliss 1991).

Peers

Peers also play a significant role in shaping a child’s understanding of gender roles. Children often react when their peers deviate from expected gender behaviors. For instance, boys are more likely to face criticism from their peers if they engage in behaviors considered “gender-bending” compared to girls. Consider this: What do we usually call a girl who enjoys wearing boys’ clothes? That’s right, a “tomboy.” But what about boys who prefer feminine attire? In the book “Dude, You’re A Fag,” sociologist C. J. Pascoe (2012) discusses how the concept of the “fag” is used as a way to regulate boys’ behavior, focusing more on gender norms than sexuality itself.

Negative reactions from peers, especially from those of the same gender, often lead to changes in behavior. This feedback reinforces traditional gender roles, restricting children’s freedom to express their gender in diverse ways.

School

Teachers also play a role in shaping how girls and boys experience education; it’s important to note that they’re not to be blamed for reinforcing gender norms. They’re just one part of a larger picture! Schools often prioritize qualities traditionally associated with femininity, like being quiet, obedient, and passive. As a result, girls typically enjoy school more and perform better academically than boys, especially in the early grades. Even in preschool, boys receive more criticism from teachers, who may unintentionally treat children based on gender stereotypes. Unfortunately, there’s often a lack of awareness about research findings, such as the fact that girls perform just as well as boys in most areas of math. This lack of awareness may lead parents and others to unintentionally discourage girls from excelling in these subjects.

Media and toys

Children begin watching TV at a very young age, typically around 18 months old. Television holds significant sway over young minds, being one of the most influential forms of media. Since young children often struggle to differentiate between fantasy and reality, they are particularly susceptible to the portrayals of gender roles on television, especially in cartoons, which dominate children’s TV viewing from ages two to eleven. As a result, children may use the depictions of males and females in cartoons as templates for their own gender performance, aiming to conform to societal norms.

In a study analyzing 175 episodes from 41 different cartoons, researchers observed significant disparities in the prominence and portrayal of male and female characters. Males were consistently given more screen time, appeared more frequently, and had more dialogue compared to their female counterparts (Thompson and Zebrinos 1997). This research underscores the powerful influence of television on shaping children’s perceptions of gender roles in society. Susan Witt (2000) suggests traditional gender roles, which encourage men to be assertive leaders and women to be submissive and reliant, are detrimental, especially to women. These roles limit the spectrum of expression and achievement. It is essential for children to grow in a gender-neutral environment that fosters a sense of belonging and encourages everyone to fully participate in society.

Numerous factors beyond the family contribute to the way we learn about gender roles. In media like television and children’s books, masculine and feminine roles are often depicted in ways that reinforce stereotypes. For instance, men are commonly shown as aggressive, competent, rational, and powerful in the workforce, while women are frequently portrayed as focused on housework or childcare (Louie and Louie 2001).

Children’s books often follow gendered themes: boys’ books may feature robots, dinosaurs, astronauts, and sports, while girls’ books may emphasize princesses, fairies, makeup, and fashion. There’s nothing inherently wrong with these themes, but it becomes problematic when they’re consistently presented as exclusively for one gender. After all, girls can enjoy adventure and pirates, and boys can appreciate cute animals and dressing up. Why limit children’s interests based on their gender?

Parents and guardians are usually the ones who buy toys for children, meaning young kids typically have little say in what toys they have at home. After all, they’re not the ones doing the shopping, are they? Unfortunately, this often leads to parents selecting toys that are specific to gender and reinforcing play behaviors that align with gender stereotypes (Witt 2000). For instance, research has found that girls’ rooms tend to have more pink items, dolls, and toys that encourage nurturing play, while boys’ rooms are more likely to have blue items, sports gear, tools, and toy vehicles (Witt 1997).

Gender Research

Margaret Mead’s (2003) groundbreaking work became a pivotal force in the women’s liberation movement and played a significant role in reshaping the perception of women in many Western societies. Her research, focused on the gender dynamics of three tribes—Arapesh, Mundugamor, and Tchambuli—triggered a national dialogue that prompted many to reassess conventional assumptions about sex and gender.

In her studies, Mead discovered intriguing variations in gender roles across these tribes:

- Among the Arapesh, both men and women exhibited what were traditionally considered feminine traits, such as sensitivity, cooperation, and low aggression levels.

- In the Mundugamor tribe, both genders displayed characteristics typically associated with masculinity: insensitivity, uncooperativeness, and high levels of aggression.

- In contrast, the Tchambuli tribe challenged conventional gender norms, with women being assertive, rational, and socially dominant, while men assumed passive roles focused on artistic and leisure pursuits.

Mead’s findings led her to question the prevailing belief that reproductive roles determined cultural and social opportunities. She pondered whether our own society had progressed similarly to these tribal cultures, challenging the idea that biology alone dictated gender roles. Instead, she proposed that tradition and culture exerted a stronger influence than biology.

Mead’s work fundamentally altered perceptions of sex and gender, advocating for the understanding that biology is only one aspect of the complex interplay between sex and gender. She emphasized that sex does not necessarily dictate gender. Despite criticism, Mead’s research underscored the influential role of culture in shaping gender dynamics, highlighting the importance of considering both biological and cultural factors in understanding how men and women are treated in society.

Gender Diversity & Norms

Cultural gender-role standards differ not only within the United States but also across various cultures worldwide. In the U.S., for instance, these standards can differ based on factors like ethnicity, age, education level, and occupation. Now, having looked at how sex and gender are defined and constructed, let’s take a closer look at some traditional gender norms from cultures that don’t entirely conform to Eurocentric, Westernized gender norms.

North America

In traditional Zuni culture, there’s a group called lhamana, who are male-bodied individuals taking on social and ceremonial roles typically carried out by women. They wear a mix of men’s and women’s clothing and often work in areas traditionally assigned to Zuni women. Additionally, they’re known for their role as mediators (Bost 2003).

Among the Mojave in North America, distinct institutional structures were established for both males and females (Roscoe 1988). For instance, husbands and wives collaborated in farming, with men handling planting and watering, and women managing the harvest. Both genders participated in storytelling, music, artwork, and traditional medicine (Hill 1935).

In Mojave society, pregnant women believed they could predict the biological sex of their children through dreams, sometimes hinting at their child’s future gender variant status. Boys displaying unusual behavior before their puberty ceremonies might undergo a two-spirit ceremony to confirm their status. During this ceremony, witnessed by the community, if the boy danced like a woman, he would be recognized as an alyha, with his gender status permanently changed. Alyha would then adopt aspects of female life, including menstruation, puberty rituals, and roles as healers, particularly in treating sexually transmitted diseases.

Many other Native American tribes had similar rituals for children displaying non-conforming gender behavior, with each tribe having unique traditions. Today, various Native American cultures recognize and have specific terms for two-spirit individuals, such as nàdleehé among the Dinéh (Navajo), winkte among the Lakota (Sioux), lhamana among the Zuni, mexoga among the Omaha, achnucek among the Aleut and Kodiak, ira’ muxe among the Zapotec, and he man eh among the Cheyenne (Nanda 1999).

In traditional Hawaiian culture, there was a celebration of diverse expressions of gender and sexuality as authentic aspects of being human. Throughout Hawaiian history, individuals known as “māhū” emerged, identifying their gender between male and female. Among the Kanaka Maoli indigenous people, there existed a tradition of multiple genders. Māhū could be biological males or females occupying a gender role that encompassed both masculine and feminine characteristics or fell somewhere in between. They held a revered social role as educators and preservers of ancient traditions and rituals. However, with the arrival of Europeans and the colonization of Hawaii, native culture was nearly eradicated, leading to discrimination against māhū in a society heavily influenced by white Eurocentric ideals (Perkins 2013).

Mexico

In Juchitán, located in Oaxaca, Mexico, gender norms differ significantly from traditional Western practices. Women here typically manage businesses, wear vibrant traditional attire, and exude confidence. They’re seen as empowered individuals, and the community has a long-standing acceptance of homosexuality and transgender individuals as part of their cultural tradition. Men who adopt traditional female roles, known as “Muxes,” are not only welcomed but also celebrated as symbols of good fortune (Maiale 2010). This community represents a unique gender system that deviates from the binary gender classifications prevalent in many other cultures worldwide.

India

In Indian Hindu culture, compared to indigenous North American cultures, the gender system is predominantly binary, but the concepts themselves differ significantly from Western perspectives, often rooted in religious beliefs. Some Hindu myths depict androgynous or hermaphroditic ancestors, a theme echoed by ancient poets through imagery blending physical attributes of both sexes. These ideas persist in Hindu culture, even becoming institutionalized. The most well-known group embodying this is the hijras (Nanda 1999). Today, hijras are not categorized as male or female but rather as “hijra.” Being a hijra involves a commitment that provides social support, some economic stability, and a cultural identity, connecting them to the broader community (Nanda 1999).

Brazil

In Brazilian culture, while a gender binary exists, it differs from the traditional Western model. Instead of strictly categorizing individuals as men and women, certain regions of Brazil classify them as men or “not-men.” Men are associated with masculinity, while those displaying feminine traits are labeled as “not-men.” This classification stems from the notion that gender is determined by sexual penetration, with individuals who are penetrated considered “not-male.” Regardless of sexual orientation, anyone not fitting this criterion is still regarded as male in Brazilian society (Kulick 1997).

Among the groups most frequently discussed concerning gender in Brazil are the travestí, who are transgender sex workers. Unlike in indigenous North American and Indian cultures, the travestí’s existence isn’t rooted in religious beliefs; rather, it’s an individual choice. Born as males, they undergo significant transformations to appear more feminine. However, they acknowledge they are not female and cannot fully transition into female. Instead, their culture revolves around this notion of being either a man or “not-man” (Kulick 1997).

Thailand

In Thailand, the term “kathoey” is used by both men and women to describe individuals who cross-dress and adopt identities that differ from their assigned birth gender, encompassing both masculine and feminine traits. Historically, until the 1970s, individuals of all genders who engaged in cross-dressing could be referred to as kathoey. However, the term is now specifically used for male individuals who are transgender. Feminine females who cross-dress are now called “tom” (Nanda 1999). Consequently, “kathoey” is commonly understood today as a category for male transgender individuals, often referred to colloquially as “lady-boys” (Nanda 1999).

The term “kathoey” originates from a Buddhist myth depicting three original human sexes/genders: male, female, and a biological hermaphrodite, known as “kathoey.” Unlike merely being a variation between male and female, “kathoey” is viewed as an independent third sex in Thai culture.

Nigeria

In Nigerian Yoruba society, social dynamics and gender roles diverge from those in the Western world. Instead of emphasizing gender differences, the culture primarily emphasizes age distinctions. The Yoruba language lacks strong gender distinctions, and their traditional culture maintains gender balance. This cultural perspective sheds light on alternative ways of understanding gender, which are common among various indigenous communities. Furthermore, men who opt to wear women’s attire, jewelry, and cosmetics are designated as “wife of the god,” as the role of wife is traditionally associated with women in relationships with mortal men (Case 2016).

Indonesia

In Indonesia, the term “waria” refers to a third gender outside of the conventional masculine and feminine norms in this predominantly Islamic country. Waria individuals are biologically male but exist along a spectrum of gender identity that goes beyond traditional Western notions of masculinity. The term encompasses individuals who may identify as male but exhibit feminine traits, occasionally wearing makeup, jewelry, and women’s clothing. Some waria identify so strongly as female that they can seamlessly pass as female in their everyday interactions within society (Boellstorff 2004).

Australia

In Australia, indigenous transgender individuals are referred to as “sistergirls” and “brotherboys.” Like in some other indigenous cultures, historical evidence suggests that transgender and intersex individuals were widely accepted before colonization. However, the influence of Eurocentric ideas on Western gender norms has led to increased stigma surrounding sistergirls and brotherboys in contemporary Australian society. Despite this, the emergence of more support groups tailored to these individuals suggests the potential for change. Gender, as we’ve seen, is constantly evolving and reshaping, reflecting the dynamic nature of societal constructions (Pullin 2014).

Gender Inequality & Oppression

In certain cultural traditions, females face significant challenges compared to males. These challenges include depriving females of nutrition, abandonment by husbands and fathers, abuse, neglect, violence, displacement as refugees, diseases, and childbirth complications, often exacerbated by lack of government support. Oppression refers to the systemic mistreatment of a particular group of people, which can manifest in various ways. This mistreatment can include cultural and symbolic forms, such as unrealistic standards of beauty and success, as well as material forms, like structured neglect or deprivation that affect certain groups more than others (Launius and Hassel 2022). While instances of sexism, classism, racism, and other forms of oppression can occur on a personal level, sociologists use the sociological imagination to examine these issues on a larger scale, focusing on how they influence cultural, economic, social, and material structures. To understand the historical oppression of women, it’s essential to consider three key social factors across different societies: religion, tradition, and economic dynamics driven by labor supply and demand.

Religion

In most of the world’s major religions, such as Christianity, Islam, Hinduism, Judaism, and others, there are clear expectations regarding gender roles. These expectations dictate what is considered normal, desirable, acceptable, and expected behavior for males and females in various roles within societies and organizations throughout their lives. These gender roles significantly influence the daily lives and activities of individuals living under religious cultures both historically and in contemporary times.

For instance, religious texts like the Book of Leviticus in the Judeo-Christian Old Testament include numerous rituals related to women’s hygiene, despite lacking scientific evidence supporting their health benefits or relevance to reproduction. These rituals were part of religious codes rather than scientifically justified practices.

Many ancient religious texts discuss perceived flaws of females, their reproductive challenges, their temperament, and regulations governing their conduct within religious communities. While some religious doctrines have evolved to reflect modern values of gender equality, religion often continues to justify gender inequality in patriarchal societies.

Throughout history, religions have wielded significant influence in many societies, with religious doctrines often reinforcing cultural values that subordinate women to men in various ways. For example, passages like Genesis 2:18 and 3:16 in the Bible depict Eve as an afterthought and suggest a hierarchical relationship between men and women, with man created in the image of God and woman as a secondary creation.

It’s worth noting that interpretations of religious texts can vary widely based on individual and community perspectives, influenced by the social construction of reality. Different groups may interpret the same scriptures differently, shaping their understanding and behavior in diverse ways. Thus, it’s not just the words of the scriptures themselves but also the collective interpretation and construction of their meaning that influence how they are understood and applied in society.

Traditions

Alongside religion, tradition is another powerful social influence. Traditions have often been harsh towards women. Even though, on average, women live three years longer than men worldwide, and seven years longer in developed countries, there are still some countries where cultural and social oppression directly results in shorter life expectancies for women. These oppressive practices persist both publicly and privately.

Although pregnancy itself is not a disease, it poses significant health risks, particularly when governments fail to allocate resources to support expectant mothers before, during, and after childbirth. Maternal death refers to the death of a pregnant woman due to complications arising from pregnancy, delivery, or recovery. In 2017, an estimated 295,000 women died from pregnancy or childbirth-related causes, with a majority succumbing to severe bleeding, sepsis, eclampsia, obstructed labor, or the consequences of unsafe abortions – all of which have highly effective interventions available (UNFPA 2019). Preventing infections, managing complications, and assisting mothers typically require minimal medical attention.

Addressing this issue necessitates a comprehensive approach at the societal level, involving government policies, healthcare systems, economic support, family dynamics, and other institutional efforts. In 2017, the maternal mortality rate was significantly higher in low-income countries, with 462 maternal deaths per 100,000 live births, compared to 11 per 100,000 live births in high-income countries (World Health Organization 2019).

Female genital mutilation (FGM) involves the traditional cutting, circumcision, or removal of most or all external genitalia from women, resulting in the closure of some or part of the vagina until marriage when it’s cut open. This practice is often carried out to uphold the perceived purity of females before marriage, which is an ideal in certain cultures. Some traditions have religious influences, while others are rooted in customs and rituals passed down through generations. However, it’s important to note that the main body of any major world religion does not endorse or mandate this practice. Female genital mutilation predates Islam, although it is prevalent in some predominantly Muslim countries where local traditions have distorted the original teachings of the religion (Obermeyer 1999).

Female genital mutilation has no medical or therapeutic benefits and can lead to various adverse medical consequences, including pain, complications during childbirth, illness, and even death. Despite efforts from numerous human rights groups, the United Nations, scientists, advocates, the United States, the World Health Organization, and others, progress in eradicating this practice has been slow. One challenge is that women often perpetuate the ritual and continue the tradition as it was imposed upon them.

Foot binding was a practice in China that, much like the obsession with tiny waists in Victorian England, symbolized the epitome of female refinement. In families with daughters eligible for marriage, foot size served as a form of social currency and a way to climb the social ladder. Small feet were considered a sign of wealth, as women with bound feet couldn’t engage in strenuous work for extended periods. This economic status eventually became a symbol of sexual desirability for potential suitors. Even though foot binding has ancient roots, it persists in some regions today. Although it’s banned in China, there are still instances of women and girls practicing foot binding.

The most sought-after bride possessed a foot measuring three inches, referred to as a “golden lotus”(Gates 2014). Having four-inch feet, known as a “silver lotus,” was also respectable. However, feet measuring five inches or longer were deemed too large and dubbed “iron lotuses.” Girls with feet this size had limited marriage prospects (Gates 2014).

To put it into perspective, imagine holding up your iPhone. Regardless of the model, its length is close to five inches. So, feet the size of your iPhone were considered less attractive, reducing a woman’s chances of marrying into high social status. In fact, even women with feet just one inch shorter than the iPhone were not valued as highly as those with feet two inches shorter.

How does foot binding work? First, starting around the age of two or three, a girl’s feet were soaked in hot water and her toenails trimmed short. Then, all her toes, except the big toe, were bent and pressed flat against the sole, creating a triangular shape. The foot was then bent double, straining the arch. Finally, the foot was tightly bound using a silk strip measuring ten feet long and two inches wide. These bindings were removed briefly every two days to prevent infections. Sometimes, any “excess” flesh was trimmed or left to rot. Girls were made to walk long distances to accelerate the breaking of their arches. As time passed, the bindings became tighter and the shoes smaller, crushing the heel and sole together. After about two years, the process was complete, resulting in a deep cleft that could hold a coin in place. Once a foot had been crushed and bound, its shape could not be reversed without subjecting the woman to the same pain all over again (Smithsonian Magazine 2015).

Indeed, despite its incredible nature, foot binding was endured and enforced by women themselves. While the practice is now condemned in China— the last shoe factory producing lotus shoes operated until 1999—it persisted for a millennium, partly due to women’s social adherence to the tradition.

Child marriage, which is when someone gets married or enters into an informal union before turning 18, affects both boys and girls, although girls are disproportionately impacted (UNICEF 2022). Currently, approximately one-third of women aged 20-24 in the developing world were married as children. Those who marry before 18 face higher risks of domestic violence, marital rape, and even homicide.

According to a recent UNICEF report, around 10 million girls are married off before they turn 18 worldwide each year. While most child marriages occur in sub-Saharan Africa, India contributes significantly to this issue as well.

In India, child marriages are against the law and those involved can face fines and up to two years in prison. However, this tradition is deeply rooted in Indian culture, particularly in remote villages, where the entire community often supports it. It’s rare for anyone to report these marriages to the police, making it difficult to stop them.

Child marriage is mainly driven by gender inequality, disproportionately affecting girls. Globally, girls are six times more likely than boys to be married off before they turn 18. In some societies, girls are viewed as financial burdens, and marriage shifts this responsibility to the girl’s husband. Economic hardships, including dowry expenses, may prompt families to marry off their daughters at a young age to alleviate financial strain.

Patriarchy, social class, and caste also play significant roles in shaping attitudes and expectations regarding the roles of women and girls. In many communities where child marriage is prevalent, rigid norms confine girls to roles as daughters, wives, and mothers. Girls are often regarded as possessions of their fathers and later, their husbands. Limited educational opportunities for girls, particularly in rural areas, further expose them to the risks associated with child marriage.

Sexual violence is a form of oppression that disproportionately affects women. Rape, an unlawful act involving forced sexual intercourse or threats of harm against a person’s will, is a global issue (Amnesty International 2008). However, it is more prevalent in the United States compared to most other countries worldwide. Among the 195 countries globally, the U.S. consistently ranks in the top five percent for incidents of rape. South Africa has the highest rates of all crimes, including rape, according to consecutive studies conducted by the United Nations (United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime 2024).

Women aged 15 to 44 are at a higher risk of experiencing rape and domestic violence than they are of cancer, motor accidents, war, or malaria, as reported by the United Nations using World Bank data (United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime 2024). A study by the U.S. Bureau of Justice Statistics in 2000, which defines rape as forced penetration by the offender, found that 94% of reported rape victims are female, while 6% are male (Renninson 2000).

Most rapes in the United States go unreported, according to various sources, including the American Medical Association (1995). Sexual violence, particularly rape, is considered one of the most under-reported violent crimes (National Institute of Justice 2010). Victims often cite reasons such as fear of retaliation, shame, and self-blame for not reporting the rape. Under-reporting affects the accuracy of data on sexual violence.

The practice of forced veiling or covering females’ bodies from head to toe has sparked both opposition and support. Various religious groups, including Christians and Hindus, have historical traditions of veiling or covering. However, in the past three decades, certain fundamentalist Muslim nations and cultures have reverted to more traditional practices. The term “hijab,” meaning to cover or veil in Arabic, has become increasingly common. In daily life, hijab often signifies modesty and privacy.

While some individuals in certain countries view hijab as a personal choice, for others, it’s enforced through laws mandating veiling. Such laws violate human rights, including equality, privacy, and freedom of expression and belief (Amnesty International 2019). Previously, the Taliban even imposed the death penalty for non-compliance, along with restrictions on women’s education and use of makeup. Many women’s rights groups have raised concerns about this trend. It’s not just about the act of covering females, but rather, it symbolizes religious, traditional, and labor-related forms of oppression that have plagued women and persist today.

Misogyny appears in various forms, including male privilege, patriarchy, gender discrimination, sexual harassment, belittlement, violence against women, and sexual objectification (Code 2000). The public denigration of women has been tolerated across different cultures because it aligns with the prevalent attitudes and interactions in daily life, where those who are privately undervalued or deemed flawed are publicly demeaned. Misogyny, characterized by the hatred and mistreatment of women, often manifests as physical or verbal abuse and oppressive behavior towards women. Misogynistic language comes in many shapes and leads to undesirable consequences. It can perpetuate harmful masculine ideals, reinforce dominant gender norms, oppress women, and constrain men from expressing their gender more freely (Moloney and Love 2018).

Gender Disparities in the U.S.

Gender inequality remains a pervasive issue in the United States, spanning across various domains of society. This section delves into several key aspects of gender inequality, shedding light on the persistent challenges faced by women. Wage disparity continues to plague the workforce, with women earning less than men for comparable work, perpetuating economic disparities. In the realm of politics, women still struggle for equal representation and face barriers in breaking the highest political glass ceiling. Gender violence, including intimate partner violence, rape, and sexual assault, remains prevalent, highlighting the alarming rates of violence experienced by women. Moreover, the use of misogynistic language perpetuates harmful stereotypes and attitudes towards women, contributing to a culture of discrimination and oppression. Through an examination of these interconnected issues, this section aims to elucidate the multifaceted nature of gender inequality and the ongoing efforts towards achieving gender equity in the United States.

Wage disparity

Wage gaps between men and women are often explained by differences in labor supply and demand. Statistics reveal historical and ongoing inequalities, with women typically earning less than men. In a 1997 presentation to the United Nations General Assembly, Diane White highlighted that American women lose an estimated $250,000 over their lifetimes due to this wage gap (United Nations 2024). Nationally, women working full-time, year-round jobs earn a median annual pay of $40,742, while men in similar positions earn $51,212, resulting in women being paid 80 cents for every dollar paid to men (U.S. Census Bureau 2022).

The wage gap is even wider for women of color. For instance, African American women earn approximately 63 cents and Latinas earn just 54 cents for every dollar earned by white, non-Hispanic men (U.S. Census Bureau 2022). Asian women fare slightly better, earning 85 cents for every dollar earned by white, non-Hispanic men, though specific ethnic subgroups may experience more significant disparities.

Why do women receive lower wages? Part of the explanation lies in traditional views of women’s roles as primarily reproductive, which are often considered inferior or supplementary. These beliefs, coupled with the perception that reproductive responsibilities disrupt work continuity, contribute to wage disparities. Outdated notions and economic factors have perpetuated the practice of paying women less than men for comparable work, despite similar levels of education, experience, and effort.

Politics

Women have faced numerous challenges in American politics, from fighting for their right to vote to advocating for equal representation in decision-making roles. Despite legislative efforts to promote gender equality, discrimination against women persists in the political arena. It wasn’t until 1981 that the first woman, Sandra Day O’Connor, was appointed to the Supreme Court, followed by Ruth Bader Ginsburg. In 2024, four out of the nine sitting justices are women: Sonia Sotomayor, Elena Kagan, Amy Coney Barrett, and Ketanji Brown Jackson.

In 1996, Madeline Albright became the first female Secretary of State, a position later held by Condoleezza Rice and Hillary Clinton. Women’s presence in politics gained significant attention during the 2008 election when Hillary Clinton ran for the Democratic nomination against Barack Obama, becoming the first woman with a substantial chance of securing a major party’s nomination. However, her candidacy faced scrutiny regarding her appearance and style, highlighting persistent gender biases.

Despite some progress, gender stereotypes continue to affect perceptions of female politicians. Data from a 2006 study showed that both male and female voters tended to view men as more competent politicians than women (Sanbonmatsu and Dolan 2007). In 2024, women hold only 24 out of 100 seats in the Senate, constituting 24% of its members, and 104 out of 535 seats in Congress, representing 27% of total seats. While this marks a significant increase compared to a decade ago, it still falls short of reflecting the proportion of women in the U.S. population.

Gender violence

Gender-based violence refers to violence directed against an individual because of their gender (European Institute for Gender Equality 2014). Shockingly, in the United States, nearly 20 people are physically abused by an intimate partner every minute. This adds up to over 10 million women and men experiencing such abuse in a single year. Studies show that approximately 1 in 3 women and 1 in 4 men have encountered some form of physical violence from an intimate partner during their lifetime. Additionally, about 1 in 5 women and 1 in 7 men have suffered severe physical violence from an intimate partner in their lifetime. Disturbingly, 1 in 7 women and 1 in 18 men have been stalked by an intimate partner to the extent that they felt intense fear for their safety or the safety of someone close to them (Black et al. 2011).

Intimate partner violence constitutes 15% of all violent crimes. This type of violence has severe repercussions on physical, mental, and sexual health. It has been associated with various health issues such as adolescent pregnancy, unintended pregnancy, miscarriage, stillbirth, nutritional deficiencies, gastrointestinal problems, neurological disorders, chronic pain, disabilities, anxiety, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), and non-communicable diseases like hypertension, cancer, and cardiovascular diseases. Moreover, individuals who are victims of domestic violence are at a heightened risk of developing addiction to alcohol, tobacco, or drugs (World Health Organization 2013).

Rape and sexual assault

The United States Justice Bureau defines rape as “forced sexual intercourse, including psychological coercion and physical force, where penetration by the offender(s) occurs. This definition encompasses attempted rapes, with victims of both genders and of various sexual orientations, including heterosexual and same-sex rapes. Attempted rape also includes instances of verbal threats of rape” (Bureau of Justice Statistics 2024). Shockingly, one in five women and one in 71 men in the United States have experienced rape in their lifetime. Nearly half of female (46.7%) and male (44.9%) rape victims were assaulted by someone they knew. Among these cases, 45.4% of female victims and 29% of male victims were raped by an intimate partner. Interestingly, from 1995 to 2010, the estimated annual rate of female rape or sexual assault victimizations decreased by 58%, from five victimizations per 1,000 females aged 12 or older to 2.1 per 1,000. During 2005-2010, women aged 34 or younger, those from lower-income households, and residents of rural areas experienced some of the highest rates of sexual violence. Moreover, during the same period, 78% of sexual violence incidents involved an offender who was a family member, intimate partner, friend, or acquaintance (Walters et al. 2013).

The Justice Bureau also defines sexual assault as a “wide range of victimizations, distinct from rape or attempted rape, involving unwanted sexual contact between the victim and the offender. These acts may or may not involve force and can include grabbing or fondling, as well as verbal threats” (Bureau of Justice Statistics 2024). Shockingly, one in five women and one in 16 men experience sexual assault while in college. Despite this prevalence, 63% of sexual assaults go unreported to the police. Furthermore, various studies reveal alarming rates of sexual violence, excluding rape, among different sexual orientation groups, with higher percentages reported among bisexual individuals. Traditional gender norms and inequality are closely linked to sexual violence. When societies or systems tolerate or trivialize violence against women, rates of such violence increase. Additionally, scholars have observed that problematic forms of masculinity, often termed toxic masculinity, can contribute to men’s violence against women. This phenomenon arises when masculinity is equated with physical force and violence, reinforcing aggressive, dominant, or hypersexual behavior (Jhally et al. 1999; Kimmel 2013).

Misogynistic language

Misogyny takes various forms, including male privilege, patriarchy, gender discrimination, sexual harassment, the belittling of women, violence against women, and sexual objectification (Code 2000). Sadly, demeaning women in public has often been deemed acceptable across different cultures because it aligns with how society privately devalues and perceives them as flawed. Misogyny, characterized by hatred towards women, frequently manifests through physical or verbal abuse and the oppressive mistreatment of women.

The use of misogynistic language yields numerous negative consequences. It can perpetuate harmful ideals of masculinity, reinforce dominant gender norms, oppress women, and limit men’s ability to express their gender freely (Moloney and Love 2018). Additionally, linguistic sexism is a significant concern, as it involves discrimination rooted in assumptions about biological sex, often leading to the belief that men are inherently superior to women. Misogyny can be seen as an extreme and violent expression of sexism.

Efforts have been made by professional and volunteer organizations to raise awareness about the demeaning language prevalent in English, which often perpetuates biases against women, people of color, the economically disadvantaged, and non-royal individuals. By discussing and addressing the assumptions embedded in language, we contribute to social transformation towards fairness and equality, both culturally and biologically. Understanding the influence of language on our culture and how cultural values impact our treatment of one another underscores the significance of language in shaping our quality of life. For instance, language perpetuates unequal connotations such as master—mistress, bachelor—spinster, and generic terms like “he” or “man” in professions such as policeman or fireman, which exclude women.