3.2 Sexual Response

Sexual response is a complex interplay between biological factors and social influences. Each person has a natural level of arousal in response to sexual stimuli, akin to how some individuals react strongly to loud noises or have varying pain thresholds. Life experiences over time further shape and modify these responses. Individual differences in how sexual stimuli are perceived affect the desire to engage in particular sexual behaviors. Social factors, such as societal norms and attitudes surrounding certain sexual activities, can also impact this process by shaping perceptions of touch and sexual contact. Let’s examine different aspects of the nervous system involved in sexual response.

Sex on the Brain

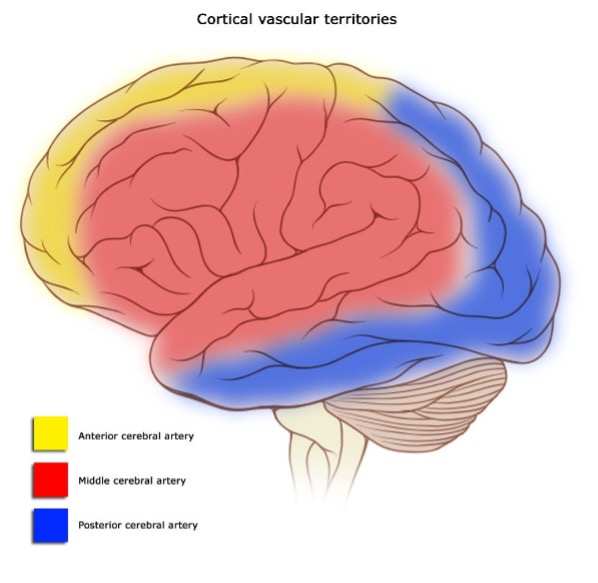

Figure 3.2 Regions of the Brain During Pleasure Experiences

“Brain and brainstem normal human diagram” by Frank Gaillard is licensed CC BY 2.5

Upon initial observation or tactile exploration, the clitoris and penis might appear to be the primary sources of pleasure within our bodies. However, the true seat of pleasure lies within our central nervous system. When experiencing pleasure, various regions of the brain and brainstem become highly active. These include the insula, temporal cortex, limbic system, nucleus accumbens, basal ganglia, superior parietal cortex, dorsolateral prefrontal cortex, and cerebellum (Ortigue et al. 2007). Neuroimaging methods have revealed that these brain regions are engaged during instances of spontaneous orgasms, even without direct skin stimulation (Fadul et al. 2005). Similarly, when individuals self-stimulate erogenous zones, these brain areas show heightened activity (Komisaruk et al. 2011). Erogenous zones are specific areas of the skin connected to the somatosensory cortex in the brain through the nervous system.

The somatosensory cortex (SC) is a region in the brain that plays a key role in processing sensory information from the skin. It’s like the brain’s hub for understanding what you feel on your skin. Interestingly, the size of the area in the somatosensory cortex dedicated to a particular part of your skin corresponds to how sensitive that part is. For instance, areas like your lips, which are very sensitive, have larger representations in the somatosensory cortex, while less sensitive areas like your trunk have smaller representations (Penfield and Boldrey 1937). When you touch a sensitive part of your body, like your lips, your brain typically interprets the sensation in one of three ways: 1) “That tickles!” 2) “That hurts!” 3) “That feels good, do it again!” This means that more sensitive areas of our bodies have the potential to create pleasure sensations.

A study conducted by Nummenmaa et al. (2016) explored this idea further. They showed participants images of bodies and asked them to mark which areas would feel sexually arousing when touched during masturbation or sex with a partner, for both themselves and members of the opposite sex. The study found expected “hotspot” erogenous zones like the genitals, breasts, and anus, but also identified other areas of the skin that could trigger sexual arousal. Nummenmaa et al. (2016) concluded that touching plays a significant role not only in physical pleasure but also in strengthening emotional bonds between partners during sexual activity.

Sensation & Perception

Sensation refers to how the nervous system processes information from the environment including stimuli like light, sound, smell, and touch/pain. Let’s focus on touch within the realm of sensory experience. In this context, transduction is a key process. Receptors in the skin send signals of touch to transmitters in the spinal cord, which then convert these signals into neural messages interpreted by the brain. The brain then prompts responses through effectors, which are neurons within muscles. For example, if something hot touches your hand, this process might lead to a reflexive jerking away of the hand to avoid injury. Perception, on the other hand, involves how individuals attribute meaning to their sensory experiences. Consider the example of masturbation. Physical sensations from touching oneself activate receptor sites and the nervous system, leading to arousal. However, the interpretation of this arousal can be influenced by internal dialogue, such as thoughts about the morality of masturbation. It’s important to recognize how societal attitudes, particularly those related to pleasure and sensuality, can shape our perceptions of our physiological experiences.

Discovering your erogenous zones: Which parts of your body do you find especially enjoyable to touch? Besides the genitals, there are several common areas to explore such as the lower back, inner thighs, lips, nipples, feet, and hands. Remember, each person may have unique spots that bring pleasure, so it’s worth exploring this question with your sexual partners too.

Sensate focus is a method sometimes used in sex therapy to help individuals gain better control over their physiological responses and understand their partner’s pleasure zones, all without directly stimulating the genitals. Many people feel anxious about being sensual as it can make them feel vulnerable and uneasy. Incorporating elements of cognitive-behavioral therapy and behavioral modification, sensate focus shifts the focus onto sensory experiences and aims to change the way individuals perceive sexual interactions. These techniques are accessible to anyone interested and can improve sexual pleasure by promoting self-awareness and enhancing communication with partners centered on pleasure.

Hormones & Pheromones

Androgens, estrogen, and progestin attach to hormone receptor sites, facilitating the production of neurochemicals (Hyde and DeLamater 2017). When experiencing excitement and arousal, hormones like dopamine, oxytocin, and norepinephrine are released into the bloodstream. Subsequently, during orgasm, opioids and endocannabinoids are released (Hyde and DeLamater 2017). Hormones play a role in both activating and deactivating sexual arousal. Testosterone, for example, is closely associated with increasing sexual desire. Imbalances in testosterone levels, either too high or too low, can diminish sexual desire. Additionally, strong emotions like happiness, anger, anxiety, and sadness can heighten sexual arousal due to their impact on our endocrine and nervous systems. For example, both sex and aggression involve hormones like epinephrine and norepinephrine, which also function as neurotransmitters. These hormones induce feelings of excitement followed by resolution. The relationship between emotions and our physiological responses is an increasingly studied area (Hyde and DeLamater 2017).

Hormones, released into the bloodstream, play a role in sexual arousal, while pheromones are chemicals emitted outside the body, communicating information about hormonal levels and ovulation to others on a chemical level. This subconscious signaling, based on our own body’s chemistry, can attract us to others (Hyde and DeLamater 2017). Researchers continue to explore the impact of pheromones on sexual responses (Savic 2014). Studies show that individuals tend to be more attracted to the scent of others that aligns with their sexual orientation, even without additional information provided. Interestingly, the scent of individuals who are biologically related is often perceived as less attractive, possibly linked to evolutionary mechanisms that discourage unintentional incest (Savic 2014). Animal studies, particularly male monkeys, suggests that exposure to the urine of an ovulating female can lead to increases in testosterone levels (Hyde and DeLamater 2017). Pheromones are believed to influence the hormonal balance in others as evidenced by instances where women’s menstrual cycles synchronize when they spend significant time together. These findings highlight the biological and social interconnectedness among humans, illustrating how our bodies respond to chemical signals in addition to social interactions.

Physiology & Sexual Response

The brain and other sexual organs react to sexual stimuli in a consistent pattern known as the Sexual Response Cycle (SRC; Masters and Johnson 1966). This cycle consists of four phases:

- Excitement: This phase is marked by activation of the sympathetic branch of the autonomic nervous system. It leads to increased heart rate, breathing, and blood flow to sexual organs like the penis, vaginal walls, clitoris, and nipples (known as vasocongestion). Involuntary muscle movements, such as facial grimaces, may also occur.

- Plateau: During this phase, which is often considered as “foreplay,” blood flow, heart rate, and breathing intensify further. Individuals with a clitoris may experience a tightening of the outer third of the vaginal walls known as the orgasmic platform. Meanwhile, a person with a penis may experience the release of pre-seminal fluid containing sperm cells. However, this fluid release makes the withdrawal method of birth control less effective.

- Orgasm: The orgasm phase is brief but intensely pleasurable. It involves the release of neuromuscular tension and a surge of the hormone oxytocin, which facilitates emotional bonding. While the muscle contractions during orgasm often coincide with ejaculation, it’s important to note that these events are distinct physiological processes. In other words, ejaculation doesn’t always occur alongside orgasm and vice versa.

- Resolution: In this phase, the body returns to its pre-aroused state. Most individuals with a penis enter a refractory period during which they are unresponsive to sexual stimuli. The duration of this period varies depending on factors such as age, recent sexual activity, intimacy with a partner, and novelty. A person with a clitoris, in contrast, typically does not experience a refractory period, allowing them physiologically to have multiple orgasms.

It’s worth mentioning that the Sexual Response Cycle (SRC) occurs regardless of the type of sexual activity—whether it involves masturbation, romantic kissing, or various forms of sexual intercourse (Masters and Johnson 1966). Additionally, it’s important to note that while having a partner or environmental stimulus can trigger the SRC, it’s not always required for it to happen.