3.3 Sexual Scripts

In sociology, the study of sexuality revolves around understanding how society shapes our perceptions and behaviors regarding sex. This involves recognizing that our ideas about sexuality, including what is expected of us and how we express ourselves sexually, are influenced by the social environment in which we live. Our interactions with various social agents, such as family and mass media, play a significant role in shaping our sexual identities and behaviors. One way sociologists explore sexuality is through the concept of sexual scripts.

Imagine sexual scripts as blueprints or guidelines for how we should behave in sexual situations. These scripts dictate our roles in sexual expression, orientation, behaviors, desires, and how we define ourselves sexually. While we’re all sexual beings, each of us develops our own unique sexual script through socialization. Sexual socialization is the process by which we learn about sexuality; it includes when, where, and with whom we express our sexuality.

From the moment we’re born, we’re driven by biological needs and sexual urges. Sexual drives compel us to engage in sexual activity and adopt certain sexual roles. Once we’ve learned our sexual scripts, they shape how we respond to these biological urges. Our sexuality is not innate; it’s learned through cultural and social influences. While everyone’s sexual script is unique, there are common themes that reflect broader social patterns.

Many of us absorb our sexual scripts passively, through a synthesis of concepts, images, and ideals presented by society. For example, the idea that men and women are fundamentally different beings was popularized in recent years, shaping how an entire generation viewed gender dynamics.

In the United States, an increasing number of people are embracing less religious values and have a broader range of sexual experiences. Additionally, many younger generations are particularly focused on the orgasm during sexual encounters, which signifies the peak of sexual pleasure and involves physical sensations such as muscle tightening in the genital area and the release of pleasure-inducing hormones throughout the body. An orgasm is the peak of sexual pleasure experienced during sexual activity. It involves the tightening of muscles in the genital area, sensations of electricity spreading from the genitals, and a release of various hormones that induce pleasure throughout the body. Various cultures have documented sexual expression, with some even documenting methods to enhance sexual pleasure (Mukherjee 2023).

Traditional sexual scripts, which have been extensively studied, often harbor problematic assumptions. These include beliefs such as men must take charge, women should not openly express enjoyment during sexual activity, and a man’s sexual prowess is measured by his partner’s orgasm. Scripts often perpetuate gender stereotypes and hinder open communication between partners regarding sexual needs and desires. More contemporary approaches to sexual relationships emphasize shared responsibility, open communication, and mutual fulfillment of each other’s desires and needs. These modern perspectives prioritize the importance of both partners actively participating in shaping their sexual experiences to ensure satisfaction and intimacy within the relationship.

Sexual Behavior Scripts

Sexual script theory suggests that our sexual behaviors are influenced by learned patterns and interactions. These scripts are acquired from our environment and culture, shaping our actions to conform to societal expectations. These scripts, largely influenced by culture, often adhere to heterosexual norms and can be reinforced by people in our lives, societal norms, and media. Our personal experiences, both with others and internally, further shape these scripts. Consequently, our interactions with partners often reflect culturally ingrained behaviors, leading to predictable patterns within relationships (Helgeson 2012).

For instance, if a male traditionally initiates sex in a relationship, the female may wait for him to do so, establishing a pattern that may persist; patterns can become internalized and influence future relationships. Deviating from established scripts can lead to negative feelings, such as guilt or judgment, reflecting internalized societal norms (Seabrook et al. 2016).

In the United States, the heterosexual script is dominant and comprises three main components: a double standard, courtship roles, and a desire for commitment. The double standard dictates that women should be passive in sexual encounters while men are expected to be assertive. Men are often praised for sexual conquests, while women are expected to resist sex outside of committed relationships. Courtship roles prescribe men to initiate sex and pursue multiple partners, while women are expected to be desired and less experienced. In terms of commitment, women are scripted to seek intimacy and trust, while men are not necessarily bound by the same expectations (Masters et al. 2013).

Research indicates that deviating from these scripts can have consequences (Masters et al. 2013). For example, if a woman challenges traditional gender roles, a man may lose interest in pursuing a relationship further; non-conforming behavior can lead to judgment and negative repercussions. However, this underscores the importance of clear communication in relationships. Establishing expectations early can help avoid misunderstandings and uncomfortable situations.

Fantasies

Sexual behaviors and fantasies are closely related yet different. Fantasies are thoughts or images related to sexual experiences, and although they are often considered private and individual activities, they can also influence partnered sexual interactions. Ultimately, it’s up to you to decide whether to keep your fantasies to yourself or share them with others.

Leitenberg and Henning (1995) describe sexual fantasies as any form of mental imagery that stimulates sexual arousal. One frequently encountered fantasy is the replacement fantasy, where individuals imagine being with someone other than their current partner (Hicks and Leitenberg 2001). Surprisingly, over 50% of people admit to having forced-sex fantasies (Critelli and Bivona 2008). However, it’s crucial to note that having such fantasies does not imply a desire to cheat on our partners or engage in sexual assault. It’s essential to distinguish between sexual fantasies and actual sexual behaviors.

It’s worth noting that sexual fantasies are distinct from sexual desires. In his book, Tell Me What You Want (2018), sex researcher Justin Lehmiller conducted a survey involving over 4,000 Americans to explore their sexual fantasies. He gathered detailed information about their personalities, sexual histories, and demographics. Lehmiller defines sexual fantasy as a sexually arousing thought or mental image that occurs while awake, rather than during a dream. These fantasies can arise spontaneously or be intentionally summoned for various reasons such as enhancing arousal, alleviating boredom, or simply relaxing. In contrast, sexual desire refers to actions or experiences that an individual actively wishes to pursue in their sex life. It represents future plans or goals regarding sexual activities that one would like to explore at some point.

“How Men’s and Women’s Sexual Fantasies Are Similar And Different” by Dr. Justin Lehmiller is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

Understanding the distinction between fantasy, desire, and behavior is crucial, especially in discussions about fantasies with your partner(s). It’s important to recognize that these concepts are interconnected yet distinct. When communicating fantasies with your partner(s), it’s essential to clarify whether these are merely fantasies or actual desires that you wish to explore. Assuming all shared fantasies represent genuine desires can lead to misunderstandings or unnecessary conflicts. Therefore, it’s beneficial to establish mutual understanding about the purpose of sharing fantasies. Are you sharing fantasies to deepen intimacy, gain insight into each other’s desires, or arouse each other? Alternatively, are you discussing ideas for activities you both wish to explore together (Lehmiller 2021)? Clarifying these intentions can facilitate constructive communication and mutual understanding in your relationship.

Masturbation

Sexual fantasies often play a role in masturbation, which involves stimulating the body for sexual pleasure. Throughout history, masturbation has been stigmatized and labeled as “self-abuse” with false claims linking it to various negative effects like hairy palms, acne, blindness, insanity, and even death . Cultural attitudes still impact how masturbation is perceived. For example, you might have heard sayings that shame masturbation, such as “You’ll grow hair on your palms,” implying that it’s shameful and others will judge you for it. It’s crucial to reflect on your own views regarding this topic.

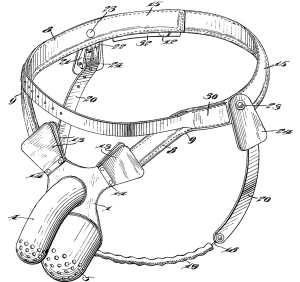

Figure 3.3 United States Early 20th Century Anti-Masterbation Chastity Belt Patent Drawing

Alfred Kinsey, a pioneer in sex research from 1894 to 1956, was one of the first to investigate Americans’ sexual behavior, including masturbation. He surveyed around 18,000 participants. Kinsey’s research revealed that women are equally interested in and experienced with sex as men, and that both genders engage in masturbation without negative health effects (Bancroft 2004). Although these findings were met with criticism initially, they spurred further exploration into the benefits of masturbation.

Many people consider masturbation to be beneficial for various reasons. It’s associated with lower stress levels, decreased engagement in risky sexual behaviors, and a better understanding of one’s own body, which can be seen as empowering and a way to embrace one’s sexuality. Clinical professionals sometimes suggest masturbation to explore physical and sensual aspects of oneself and address challenges related to sexual functioning. Research supports the idea that masturbation contributes to increased sexual and marital satisfaction, and overall physical and psychological well-being (Hurlburt and Whitaker 1991; Levin 2007). Additionally, there’s evidence indicating that masturbation can significantly reduce the risk of prostate cancer in men over the age of 50 (Dimitropoulou et al. 2009).

Masturbation is a common practice among both men and women in the United States. Robbins et al. (2011) found that 74% of men and 48% of women in the U.S. report engaging in masturbation. However, cultural influences can affect the frequency of masturbation. For example, a study in Australia found that only 65% of men and 35% of women reported masturbating; not, in the UK, 86% of men and 57% of women ages 16–44 reported masturbating within the past year (Regenerus et al. 2017). In contrast, rates of reported masturbation in India are lower, with only 46% of men and 13% of women reporting engaging in the practice (Ramadugu et al. 2011). Despite its prevalence, masturbation can be surrounded by feelings of shame and guilt for many individuals. Cultural background, family upbringing, and religious beliefs can all influence how one perceives and experiences solo sexual activity. However, it’s worth noting that, as Kinsey suggested, there are typically few, if any, negative consequences associated with masturbation, except for feelings of guilt and shame in some cases.

“Masturbation Myths” by TED is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

The Double Standard

Research into the double standard in sexual behavior began in the 1960s by Ira Reiss. Reiss explored how society allowed men to engage in premarital sexual behavior but prohibited women from doing so (Milhausen and Herold 1999). This double standard affects various aspects of sexuality such as the age of first sexual intercourse (men being younger) and the number of sexual partners (men having more). In terms of behavior, males are often praised for sexual activity and promiscuity from adolescence onwards, while females may face shame. As males increase their number of sexual partners, they tend to gain more acceptance from their peers, whereas females may experience less acceptance (Kraeger et al. 2016). Additionally, research suggests that a girl’s sexual history leads to a decline in peer acceptance, whereas boys with similar histories may see increased acceptance (Kraeger et al. 2016).

Interestingly, perceptions of the double standard differ when it comes to activities like kissing or “making out.” Girls may be more accepted by their peers for such behaviors, while boys may face less acceptance (Kraeger et al. 2016). These attitudes may not only affect perceptions but also impact actual sexual encounters. For instance, in hookups, males tend to achieve orgasm more frequently than females (Garcia et al. 2012).

While women acknowledge the existence of a sexual double standard, they often deny holding it themselves (Milhausen and Herold 1999). However, research indicates that men are more likely to hold double standards (Allison and Risman 2013). Despite challenges from young men and women, the double standard persists. While a significant portion of individuals reject the double standard, many still hold some degree of it (Sprecher et al. 2013).

Hookup Culture

A hookup refers to a situation where two people who are not in a committed relationship engage in sexual activity, which could involve intercourse, oral sex, digital penetration, kissing, and so forth. Typically, there’s no expectation of forming a romantic bond afterward (Garcia et al. 2012). This trend is becoming increasingly common among young adults in the U.S., but why? In the 1920s, attitudes towards sexual promiscuity started to shift, becoming more open and accepted. As time went on and medical advancements like birth control became available, discussing sex openly and engaging in casual sexual behavior became more widespread, breaking traditional moral and religious boundaries, such as the expectation of abstinence until marriage (Garcia et al. 2012). Nowadays, the term “friends with benefits” (FWB) describes a relationship where two individuals agree to have purely physical intimacy without emotional attachment (Garcia et al. 2012). Around 60% of college students report having been in a FWB relationship at some point.

There are some gender differences in how often people hookup and how they feel afterward. Women tend to be more conservative in their attitudes towards casual sex compared to men. Both genders report mixed feelings after hooking up, with about half of men feeling positive, a quarter feeling negative, and the rest feeling a mix of emotions. For women, it’s somewhat reversed, with about a quarter feeling positive, half feeling negative, and the rest having mixed feelings. Despite mixed feelings, around three-quarters of people overall report feeling regret after a hookup. Factors like hooking up with someone they’ve just met or only hooking up once tend to lead to regret. Men may feel regret because they feel they’ve used someone, while women may feel regret because they feel used. Women tend to be more negatively affected by hookups overall (Garcia et al. 2012).

Most college students don’t worry about contracting sexually transmitted infections (STIs) after a hookup, and fewer than half use condoms during one. Reasons for hooking up vary; substance use, especially alcohol, is often involved and can lead to unintended hookups. Feeling depressed, isolated, or lonely is also a common factor. Generally, individuals with lower self-esteem are more likely to engage in hooking up (Garcia et al. 2012). The impact of hookups varies too; some people report feeling less depressed or lonely afterward, while others may experience an increase in depressive symptoms, particularly if they didn’t have them before (Garcia et al. 2012).