4.1 Intimate Relationships

Humans share a common ancestry with both chimpanzees and bonobos, our closest living relatives in the animal kingdom (Prüfer et al. 2012). Despite significant differences between these two ape species, humans exhibit many behaviors related to relationships and sexuality that are observed in both chimpanzees and bonobos.

When it comes to mating and relationships, human males vary in their behavior, with some displaying protective and aggressive tendencies towards perceived sexual conquests, while others show respect and admiration for strong women in their lives. Similarly, societal attitudes towards sexuality vary greatly, with some cultures enforcing strict rules dictating that sexual behavior should only occur for the purpose of reproduction, while others embrace sexual fluidity for pleasure, connection, and community.

Therefore, human behavior reflects a blend of characteristics seen in both chimpanzees and bonobos, influenced by evolutionary history, societal structures, and prevailing social norms. To dig deeper into the factors driving humans to seek long-term intimate relationships, we can draw upon insights from evolutionary psychology, social psychology, current evidence-based research on healthy relationships, and critical theories that emphasize intersectionality. These perspectives offer diverse lenses through which we can better understand the complexity of human relationships.

Evolutionary Theories

The desire to pass on genes and have children may influence why some individuals choose to pursue intimate relationships. In heterosexual relationships between cisgender individuals, certain behaviors have evolved over time to enhance the likelihood of producing healthy offspring. However, it’s important to note that this perspective may not fully encompass the experiences of sexual minorities and gender-diverse individuals. As you explore sexual selection theory and sexual strategies theory, you’ll notice that they often use the term “sex” rather than “gender.” These evolutionary theories primarily focus on the biological differences in anatomy and function related to sexual behavior.

Sexual selection theory

Darwin observed that certain traits and behaviors in organisms couldn’t be explained solely by their usefulness for survival. Take the peacock’s vibrant plumage, for instance. Rather than aiding in survival, these flashy feathers actually make the peacock more noticeable to predators, increasing its risk of becoming a tasty meal. Why do peacocks have such extravagant feathers? Similar questions arise for other animals, like the large antlers of male stags or the wattles of roosters, which also seem to pose disadvantages for survival.

If these traits are seemingly detrimental to an animal’s survival, why did they evolve in the first place? And how have these animals managed to persist with these traits over thousands of years? Darwin proposed an answer to this puzzle: sexual selection. This theory suggests that certain characteristics evolve not because they improve survival, but because they enhance mating opportunities.

Sexual selection operates through two main processes. The first is intrasexual competition, where individuals of one sex compete among themselves, and the winner earns the chance to mate with a member of the opposite sex. For instance, male stags engage in battles using their antlers, with the victor, often the one with larger antlers, gaining mating access to females. Despite the disadvantage of having large antlers for survival, as they hinder agility in navigating forests and evading predators, they increase reproductive success by making stags more attractive to potential mates. Similarly, human males may compete physically in activities like boxing or team sports, enhancing their appeal to potential partners despite the potential risks to survival. Traits that lead to success in intrasexual competition are passed on more frequently due to their association with increased mating success.

The second process is preferential mate choice, also known as intersexual competition. Here, individuals are attracted to specific qualities in potential mates, such as vibrant plumage, signs of good health, or intelligence. These desired qualities become more prevalent in the population because individuals possessing them mate more frequently. For example, the colorful plumage of peacocks evolved due to peahens’ historical preference for males with brightly colored feathers.

In all sexually reproducing species, adaptations in males and females arise from both survival selection and sexual selection. However, unlike in other animals where one sex typically has control over mate choice, humans engage in mutual mate choice, where both partners have a say in selecting mates. Human preferences often prioritize qualities such as kindness, intelligence, and dependability, which are beneficial for fostering long-term relationships and effective parenting.

Sexual strategies theory

Sexual strategies theory builds upon sexual selection theory, suggesting that humans have developed various mating strategies, both short-term and long-term, influenced by factors such as culture, social context, parental influence, and personal desirability in the mating market.

Initially, sexual strategies theory focused on the contrasting mating preferences and strategies between men and women (Buss and Schmitt 1993). It considered the minimum parental investment required to produce offspring, noting that for women, this investment is substantial as they carry the child for nine months. In contrast, men’s investment is minimal, limited to the act of sex.

These differing levels of parental investment significantly shape sexual strategies. Women face higher risks associated with poor mating choices, such as partnering with unsupportive or genetically inferior mates. Consequently, women tend to be more selective in short-term mating situations. Men, on the other hand, are less selective due to lower associated costs, often engaging in more casual sexual activities. This can lead to men deceiving women about their intentions for short-term gains.

Empirical evidence supports these predictions, indicating that men generally desire more sex partners, engage in casual sex more readily, and lower their standards for short-term mating (Buss and Schmitt 2011). However, in long-term mating situations, where both parties are interested, both men and women invest substantially in the relationship and their children, leading to increased selectivity in partner choice.

While men and women generally seek similar qualities in long-term mates, such as intelligence and kindness, there are differences due to distinct adaptive challenges. Women value resource-related qualities in men, while men prioritize youth and health in women, indicating somewhat divergent preferences shaped by evolutionary pressures. Though these preferences were initially thought to be universal, emerging evidence suggests variations, particularly in industrialized western cultures. Factors like sex ratios, cultural practices, and the strategies of others also influence mate selection, complicating the straightforward application of sexual strategies theory in diverse contexts.

In summary, sexual strategies theory, rooted in sexual selection theory, highlights both commonalities and differences in men’s and women’s mating preferences and strategies. However, numerous other factors beyond evolutionary tendencies also play a role in shaping mate selection processes.

Liking & Loving Long-term

Previously, we’ve explored the dynamics of attraction between individuals just beginning to form connections. However, the fundamental principles of social psychology can also shed light on relationships that endure over time. As friendships deepen, marriages solidify, and families strengthen bonds, relationships evolve, requiring us to understand them in nuanced ways. Nevertheless, social psychology principles remain relevant in deciphering the factors contributing to the longevity of these relationships.

The elements sustaining affection and love in long-term relationships partly echo those fostering initial attraction. Even as time passes, individuals remain intrigued by their partners’ physical attractiveness, albeit with reduced emphasis compared to initial encounters. Similarly, the importance of similarity persists. Relationships thrive when partners share common interests, values, and beliefs over time (Davis and Rusbult 2001). Both perceived and actual similarity tend to increase in long-term relationships, correlating with satisfaction in heterosexual marriages (Schul and Vinokur 2000). Moreover, certain aspects of similarity, such as positive and negative affectivity, influence satisfaction in same-sex marriages (Todosijevic et al. 2005). However, demographic factors like education and income similarity may hold less significance for satisfaction in same-sex partnerships than in heterosexual ones (Todosijevic et al. 2005).

Proximity also remains crucial, as relationships strained by prolonged physical separation are more susceptible to dissolution. But what about passion? Does it endure over time? Yes and no. Individuals in enduring relationships, reporting high satisfaction, maintain feelings of passion for their partners—they still desire closeness and intimacy (Simpson 1987; Sprecher 2006). Moreover, they find their partners increasingly attractive as their love deepens (Simpson et al. 1990). However, the intense passion experienced during initial encounters is unlikely to sustain throughout long-term relationships (Acker and Davis 1992). Nonetheless, physical intimacy retains its importance over time.

As time passes, thinking becomes relatively more significant than feeling, and strong relationships often rely on companionate love. Companionate love is defined as a type of love rooted in friendship, mutual attraction, shared interests, respect, and care for each other’s well-being. This doesn’t imply that lasting love is any less powerful; instead, it might possess a different foundation compared to the initial intense love driven primarily by passion.

“The Secret to Desire in a Long-term Relationships” by TED is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

Closeness & Intimacy

While many factors influencing initial attraction remain relevant in long-term relationships, additional variables also come into play as the relationship progresses. One significant change is that as partners spend more time together, they become more acquainted with each other and develop deeper care and concern for one another. In successful relationships, this growing familiarity leads to increased closeness, whereas in unsuccessful relationships, closeness may stagnate or decline. A key aspect of this closeness is reciprocal self-disclosure, where partners communicate openly, without fear of judgment, and with empathy.

Intimate relationships, as defined by Sternberg (1986), are characterized by feelings of caring, warmth, acceptance, and social support between partners. In these relationships, individuals often view themselves and their partners as a unified entity, rather than as separate individuals. Moreover, individuals who feel close to their partners are better equipped to maintain positive feelings about the relationship, while also expressing negative emotions and making accurate judgments about their partner (Neff and Karney 2002). Additionally, people may use their partner’s positive traits to enhance their own self-esteem (Lockwood et al. 2004).

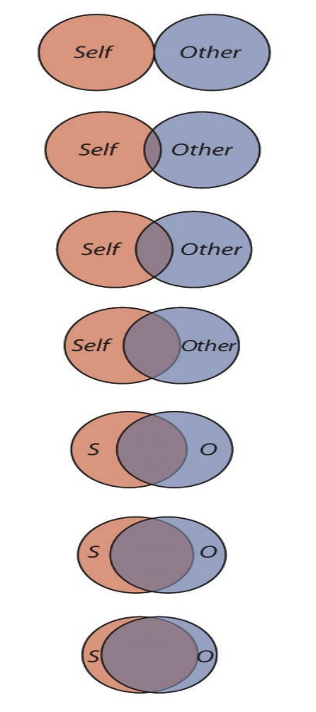

Aron, Aron, and Smollan (1992) directly assessed the role of closeness in relationships using a simple measure called “Measuring Relationship Closeness.” This measure allows individuals to assess the level of closeness in their relationships by indicating how much they perceive themselves and their partner to overlap as depicted in Figure 4.1. Completing this measure can provide insights into the level of intimacy in various relationships, such as those with family members, friends, or romantic partners. Choosing circles that overlap more indicates greater closeness, while less overlap suggests a less intimate relationship.

Figure 4.1. Measuring Relationship Closeness

Source: Goerling, Ericka & Emerson Wolfe. 2002. Introduction to Human Sexuality. Portland, OR: Open Oregon Educational Resources. Retrieved March 27, 2024 (https://open.umn.edu/opentextbooks/textbooks/1273).

This measure helps gauge the level of closeness between two partners. Respondents simply circle the figure they believe best represents their relationship (Aron et al. 1992).

Despite its simplicity, research has shown that the closeness measure is highly predictive of individuals’ satisfaction with their close relationships and their likelihood to stay together. Interestingly, the perceived closeness between romantic partners can be a more accurate predictor of relationship longevity than the number of positive feelings partners express for each other. In successful close relationships, the boundaries between self and other tend to blur, emphasizing acceptance, care, and social support as crucial factors (Aron et al. 1991).

Aron and his colleagues (Aron et al. 1997) conducted an experiment to investigate whether disclosing intimate thoughts to others would increase closeness. In this study, college students were paired with unfamiliar peers and asked to share intimate experiences by answering questions like “When did you last cry in front of another person?” Those who engaged in intimate self-disclosure reported feeling significantly closer to their partners compared to control participants who engaged in small talk (e.g., discussing favorite holidays).

Communal & Exchange Relationships

In close, intimate relationships, partners often become deeply attuned to each other’s needs, sometimes prioritizing the desires and goals of their partner over their own. This level of attentiveness and support, without expecting anything in return, characterizes what psychologists term a communal relationship. In such relationships, partners suspend the need for equality and exchange, offering support to meet their partner’s needs selflessly, without considering the costs to themselves. This is contrasted with exchange relationships, where partners keep track of contributions to the partnership.

Research indicates that communal relationships can be advantageous, with studies showing that happier couples are less likely to keep score of their respective contributions (Buunk et al. 1991). Additionally, reminders of the external benefits partners provide may decrease feelings of love (Seligman et al. 1980).

However, this doesn’t mean partners in long-term relationships always give without expecting anything in return. They may indeed keep track of contributions and benefits received. If one partner feels they are contributing more than their fair share over time, it can lead to dissatisfaction and strain in the relationship. Equity is crucial, with marriages being happiest when both partners perceive they contribute relatively equally (Van Yperen and Buunk 1990). Interestingly, our perception of equity compared to others’ relationships around us also plays a role. Those who perceive they are receiving better treatment than others tend to be more satisfied with their relationships (Buunk and Van Yperen 1991).

Furthermore, individual differences exist in how people perceive equity’s importance. Those high in exchange orientation find equity more critical for relationship satisfaction, while those low in exchange orientation may not show the same association (Buunk and Van Yperen 1991). Still they tend to be more satisfied overall with their relationships.

Ultimately, relationships that endure are characterized by partners who are attentive to each other’s needs and strive for equitable treatment. Yet, the most successful relationships go beyond mere rewards and adopt a communal perspective, focusing on the well-being of the relationship as a whole.

Interdependence & Commitment

Long-term relationships differ from short-term ones in their complexity. As couples establish households, raise children, and possibly care for elderly parents, the demands on the relationship increase accordingly. This complexity leads partners in close relationships to rely on each other not only for emotional support but also for coordinating activities, remembering important dates, and completing tasks (Wegner et al. 1991). Partners become highly interdependent, relying on each other to achieve their goals.

Developing an understanding of each other’s needs and establishing positive patterns of interdependence takes time in a relationship. The image we hold of our significant other is rich and detailed due to the time and care invested in the relationship (Andersen and Cole, 1990). Additionally, as relationships endure, particularly those involving children, the costs associated with ending the partnership become increasingly significant.

In relationships characterized by positive rapport and maintained over time, partners naturally find satisfaction and commitment. Commitment encompasses the feelings and actions that keep partners invested in the relationship. Committed partners view each other as more attractive, are less likely to consider other potential partners, and are less prone to aggression or breakup (Simpson 1987; Slotter et al. 2011).

However, commitment may also lead individuals to stay in relationships even when the costs are high. This can be attributed to the consideration of both the benefits and costs of leaving, as well as the investments made in the relationship over time, known as the sunk costs bias (Eisenberg et al. 2012). Thus, when evaluating whether to stay or leave, individuals weigh the costs and benefits of the current relationship against those of potential alternatives (Rusbult et al. 2001). While interdependence and commitment contribute to the longevity of relationships, they can also complicate breakups. The closer and more committed a relationship, the more difficult a breakup can be.

Love & Attachments

Although we’ve discussed it indirectly, we haven’t looked into defining love itself, despite its clear significance in many close relationships. Social psychologists have explored the role and characteristics of romantic love, discovering that it involves cognitive, emotional, and behavioral elements, and it’s observed across different cultures, albeit with variations in experience.

Robert Sternberg and his colleagues (Arriaga and Agnew 2001; Sternberg 1986) have put forward a triangular model of love, proposing that there are various types of love, each comprising different combinations of cognitive and emotional factors—specifically passion, intimacy, and commitment. According to this model illustrated in Figure 4.2, consummate love, which entails all three components, is likely experienced only in the strongest romantic relationships. Other types of love may involve just one or two of these components. For instance, close friends may exhibit intimacy alone, or if they’ve known each other for a long time, they might also share commitment (companionate love). Similarly, individuals in the early stages of dating might feel infatuation (passion only) or romantic love (both passion and intimacy, but not commitment).

Figure. 4.2 Triangular Model of Love by Robert Sternberg (1986)

Source: Goerling, Ericka & Emerson Wolfe. 2002. Introduction to Human Sexuality. Portland, OR: Open Oregon Educational Resources. Retrieved March 27, 2024 (https://open.umn.edu/opentextbooks/textbooks/1273).

Research investigating Sternberg’s theory has found that the importance of the different aspects of love tends to change over time. Lemieux and Hale (2002) collected data on the theory’s three components from couples at various stages of their relationship—casually dating, engaged, or married. They discovered that while passion and intimacy showed a negative association with relationship duration, commitment displayed a positive correlation with the length of the relationship. Engaged couples reported the highest levels of intimacy and passion.

In addition to these changes in the dynamics of love within relationships over time, there are intriguing gender and cultural distinctions. Despite common stereotypes, men typically express beliefs indicating enduring love and report falling in love more rapidly than women (Sprecher and Metts 1989). Regarding cultural differences, individuals from collectivist cultures generally place less emphasis on romantic love compared to those from individualistic societies. Consequently, they may prioritize companionate aspects of love more and give relatively less importance to passion-based aspects (Dion and Dion 1993).

Attachment styles

One crucial factor that influences the quality of close relationships is how partners interact with each other. This interaction can be understood through attachment styles, which reflect individual differences in how people connect with others in close relationships. Our attachment styles are evident in our interactions with parents, friends, and romantic partners (Eastwick and Finkel 2008).

Attachment styles are developed in childhood, where children form either healthy or unhealthy attachments with their parents (Ainsworth et al. 1978; Cassidy and Shaver 1999). Most children develop a secure attachment style, feeling that their parents are safe, available, and responsive caregivers. These children find it easy to relate to their parents and view them as a secure base from which they can explore the world. However, some children develop insecure attachment styles. For instance, those with an anxious/ambivalent attachment style become overly dependent on their parents and continually seek more affection than they receive. Others develop an avoidant attachment style, becoming distant and fearful, lacking warmth in their interactions.

These attachment styles established in childhood tend to persist into adulthood (Caspi 2000; Collins et al. 2002; Rholes et al. 2007). Fraley (2002) conducted a meta-analysis confirming a significant correlation between infant attachment behavior and adult attachment over a span of 17 years. Another attachment style, the disorganized style, which combines features of insecure attachment, also shows links to adulthood, particularly with an avoidant-fearful attachment style.

The consistency of attachment styles across the lifespan implies that individuals who develop secure attachments in childhood are better equipped to form stable, healthy relationships as adults (Hazan and Diamond 2000). On the other hand, insecurely attached individuals may face challenges in their relationships. They tend to exhibit less warmth, express anger more frequently, and struggle with emotional expression. Moreover, they often worry about their partner’s love and commitment, interpreting their partner’s behavior negatively (Collins and Feeney 2000; Pierce and Lydon 2001).

People with avoidant and fearful attachment styles may encounter difficulties in forming close relationships altogether. They struggle with expressing emotions, experience negative affect during interactions, and have trouble understanding their partner’s emotions (Tidwell et al. 1996; Fraley et al. 2000). They also show less interest in learning about their partner’s thoughts and feelings (Rholes et al. 2007).

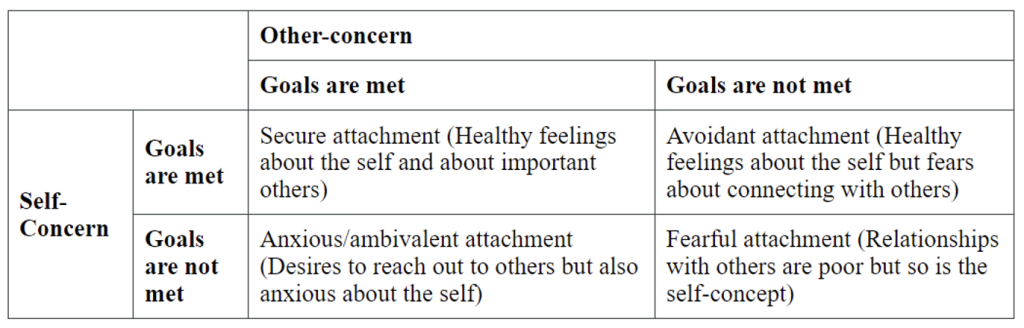

Attachment styles can be viewed in terms of meeting self-concern and other-concern goals in close relationships (see Table 4.1. “Attachment as Self-Concern and Other-Concern”). Individuals with a secure attachment style tend to have positive feelings about themselves and others. In contrast, those with avoidant attachment styles feel good about themselves but struggle in their relationships.

Anxious/ambivalent individuals are primarily other-concerned but have low self-esteem, hindering their ability to form strong relationships. The fourth category represents the avoidant-fearful style, where individuals struggle to meet both self-concern and other-concern goals.

Table 4.1. Attachment as Self-Concern and Other-Concern

Source: Jhangiani, R., & Tarry, H. 2014. Principles of Social Psychology. 1st ed. Retrieved March 27, 2024 (https://opentextbc.ca/socialpsychology/chapter/close-relationships-liking-and-loving-over-the-long-term/).

Given the significant impact of attachment styles on relationships, it’s essential to consider potential partners’ interactions with others in their lives. The quality of relationships with parents and close friends predicts the quality of romantic relationships. However, attachment styles don’t determine everything. Adults have diverse experiences that can influence their ability to form close relationships positively or negatively. Additionally, there is diversity in attachment styles across cultures, suggesting that some attachment styles may be more adaptive in certain cultural contexts (Agishtein and Brumbaugh 2013). Moreover, attachment styles can vary across different relationships and change over time with varying relationship experiences (Pierce and Lydon 2001; Ross and Spinner 2001; Chopik et al. 2013). Therapeutic interventions can leverage these findings to help individuals develop more secure attachment styles and improve their relationships (Solomon 2009; Obegi 2008).

Internet Relationships

Many of us are increasingly connecting with others through digital platforms. Online relationships are becoming more prevalent. However, you might question whether interacting online can foster the same sense of closeness and care as face-to-face interactions. Additionally, you may wonder if spending more time on social media and the internet detracts from engaging in activities with physically close friends and family (Kraut et al. 1998).

Despite these concerns, research indicates that internet usage can contribute to positive outcomes in our close relationships (Bargh 2002; Bargh and McKenna 2002). In a study by Kraut et al. (2002), individuals who reported using the internet more frequently also reported spending increased time with their loved ones and experiencing better psychological well-being.

Moreover, the internet can facilitate the formation of new relationships, with their quality often rivaling or exceeding those formed in person (Parks and Floyd 1996). McKenna et al. (2002) found that many participants in online news and user groups developed close relationships with individuals they initially met on the internet. A substantial portion of participants even reported forming real-life relationships, including marriages, engagements, or cohabitation, with internet acquaintances.

In laboratory studies, McKenna et al. (2002) compared interactions between previously unacquainted college students who met either in an internet chat room or face-to-face. Interestingly, those who initially met online tended to express greater liking for each other compared to those who met in person, even when interacting with the same partner both online and face-to-face. Additionally, people often find it easier to express their emotions and experiences to online partners than in face-to-face encounters (Bargh et al. 2002).

Several factors contribute to the success of internet relationships. The anonymity of online interactions can facilitate self-disclosure, allowing individuals to share personal information more freely. Moreover, the absence of physical attractiveness cues may lead individuals to prioritize other important characteristics such as shared values and beliefs. Additionally, the internet enables individuals to maintain connections with distant friends and family and facilitates the discovery of like-minded individuals with shared interests and values (Wellman et al. 2001).

Furthermore, online interactions can enhance offline relationships. A study by Fox et al. (2013) explored the impact of publicly declaring relationship status on Facebook, known as going “Facebook official” (FBO), among college students. They found that discussions between partners often preceded the FBO status change and that couples who went FBO reported increased perceived commitment and stability in their relationships. Rather than fostering isolation, interacting with others online helps us maintain close connections with family and friends and often leads to the formation of intimate and fulfilling relationships.