4.2 Marriage & Long-Term Relationships

Before discussing marriage, cohabitation, and other forms of relationship building, it’s crucial to consider the diversity present both at a personal and societal level within the United States and globally. As of the publication of this book, the world’s population stands at 8 billion, with 336 million individuals being citizens of the United States (U.S. Census Bureau 2024). These numbers are continually increasing, evident by visiting the website. The United States and the world are experiencing rapid population growth, resulting in a multitude of diverse individuals within our communities. With billions of people globally, diversity is abundant, ranging from various family structures such as polygamous, monogamous, and cohabiting arrangements to differing views on childbirth within and outside of marriage.

Here is an activity we use in our race and ethnicity classes, which usually have about 40 students per section. Scholars are asked to jot down the top one or two traits they admire in other people and then the top one or two traits that really annoy them. After collecting their lists, we tally up the most common admirable and annoying traits, creating ranked lists. We then spend a significant portion of class time on a sympathy-building and empathy-awareness activity.

To start, we read out the most commonly reported admirable traits one by one, pausing for anyone who feels they possess that trait to stand up. This part is usually quite fun as students awkwardly but bravely rise when I mention their trait. Eventually, almost every scholar ends up standing at least once. It can take a bit more encouragement for scholars to stand for the annoying traits, but they come to trust that it’s a safe environment. By the end, most students have stood up for both lists.

Afterwards, we ask scholars to share their observations. Many are surprised to find commonalities with their peers, realizing they’re not as unique as they thought. Some notice traits they have that bother others. This often leads to feelings of sympathy for classmates with less desirable traits. We point out how almost every scholar stood up for both admirable and annoying traits, suggesting an increased capacity for empathy, the ability to understand others’ feelings.

To help scholars grasp the diversity of modern society, we emphasize that everyone likely has traits that someone admires and others find annoying. In such a diverse world, learning to tolerate those with different backgrounds, beliefs, and traits is essential for peaceful coexistence. Tolerance is the baseline for respectful living in today’s society. Feeling sympathy for others can enhance this tolerance.

However, there’s a growing divide between liberal and cultural values, leading to not just a lack of tolerance but outright contempt for opposing views. In the past, tolerance might have been enough, but today, respecting and empathizing with those who hold different political beliefs is crucial. Respecting others, even those with opposing views, is essential in classrooms, workplaces, neighborhoods, and broader society.

If you find it challenging to respect others with differing political views, you’re not alone, as many in our society feel the same. Starting with sympathy and tolerance is a good foundation. The teachings of Reverend Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. offer valuable lessons on how to promote respect and empathy, even in the face of political differences, aligning with the principles outlined in the U.S. Constitution.

On The King Center’s website, you can find Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s philosophy regarding the three evils of racism and his suggestions for overcoming hate, contempt, mistreatment, violence, and bigotry (The King Center 2024). Dr. King didn’t just urge Americans to tolerate people of color; he called for a change in attitudes and beliefs to combat prejudice, blame, contempt, and mistreatment of those who are different. While the website contains more details, Dr. King advocated for nonviolent action, compassion, forming genuine friendships with diverse individuals, choosing love over hate, and addressing harmful actions rather than condemning individuals.

What does this mean for studying marriage and intimate relationships? It implies that, at a basic level, we should be able to tolerate people who are different. It’s important to work respectfully within the bounds of federal and state laws that protect individuals based on their “protected class” status. Protected classes include categories like race, color, religion, ethnicity, sex, sexual orientation, gender identity, national origin, disability, and medical/genetic information, with workplace protections enforced by the U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC). These protections extend to preventing mistreatment in the workplace, including discrimination, harassment, sexual harassment, and retaliation against those who file complaints. Similar rules and laws apply on college campuses.

But what about interactions at home, in public, or within religious settings? There are no laws mandating empathy, sincere friendships, or compassion. While laws exist to address hate crimes, such as those defined in criminal codes, tragic events like the murder of George Floyd highlight that laws alone cannot ensure proper behavior.

What if others pressure you to change your beliefs? It’s important to note that forcing someone to abandon their beliefs is wrong. Diversity of thought is a fundamental aspect of American society. Those who hold contempt for differing beliefs exhibit behavior akin to the arrogance Dr. King identified as one of the three evils of racism. Dr. King described it as the belief that one race (or set of beliefs) is superior to others, demanding submission (King 1963).

As sociologists, our aim is to study rather than judge, striving for objectivity in research and teaching. We invite you to apply this objectivity as we explore lifestyles that may differ from your own. We’ll also examine the widening gap between liberals and conservatives, and how legal definitions of marriage have contributed to this divide in recent decades.

ANALYZING FAMILY STRUCTURES

Supreme Court Opinions

On June 26th, 2015, the United States Supreme Court rendered a decision regarding the legality of same-sex unions. Justice Kennedy wrote that under the 14th Amendment’s equal protection provision, “couples of the same sex may not be deprived of that right and liberty.” This is a historic decision that many civil liberties experts compare to Brown vs. Board of Education and Roe vs. Wade.

As a marriage and family scholar, it is pertinent for you to read the majority opinion written by Justice Kennedy. The opinion is intended to reflect the reasoning and legal precedence behind this historic decision. Read the opinion of the court by Justice Kennedy then write a response to the following questions: https://supreme.justia.com/cases/federal/us/576/644/#tab-opinion-3427255

- State the “four principles and traditions which demonstrate that the reasons marriage is fundamental under the Constitution apply with equal force to same-sex couples” (Kennedy, 2015: 1-5).

- Fill-in-the-blank: The right of same-sex couples to marry is also derived from the Fourteenth Amendment’s guarantee of ________________________________.

- The lead plaintiff in the case, Jim Obergefell, who challenged Ohio’s ban on same-sex marriage, stated that the ruling “affirms what millions across this country already know to be true in their hearts – that our love is equal.” Throughout the written opinion by Kennedy many different couples stories were described. Which story resonated the most with you and why? What hardships were endured as cause for their case before the court?

- How does this decision affect your view of civil liberties and freedom as it relates to marriage?

“Supreme Court Opinions” by Katie Conklin, Lemoore College is licensed under CC BY 4.0

“We”

A couple is essentially a pair of individuals who perceive themselves as belonging together, trusting each other, and sharing a unique bond, distinct from all others. The concept of “We” is closely related, but it emphasizes the relationship itself as an entity. “We” often refers to a married couple, but it can also include cohabiting or other non-married intimate partnerships. This relationship stands out as deeply connected, not closely intertwined with any other relationships to the same extent as the bond between these two partners.

To illustrate, think of a “We” as akin to a jointly owned vehicle that both partners invest in maintaining. Both individuals must nurture and care for it to ensure its longevity. Sometimes, actions or words from one partner can damage the trust within this relationship. The “We” delineates the social and emotional boundaries a couple sets when they commit to each other, encompassing only the husband and wife while intentionally excluding children, extended family, coworkers, and friends.

Establishing a strong marital bond often involves distinguishing oneself as part of this “We” entity and partially disengaging from prior relationships with children, grandchildren, or close friends. This doesn’t mean cutting off ties with parents, relatives, or friends altogether. Instead, it means forging a new, exclusive intimacy reserved solely for the couple. Judith Wallerstein and Sandra Blakeslee’s book “The Good Marriage” explores this aspect.

There’s a popular saying aimed at improving marital relationships: “Marriage requires less of ‘Me’ and lots more of ‘We’.” This highlights the importance of prioritizing the collective partnership over individual needs or desires. Part of forming this “We” involves treating certain matters as “Spouse-only Issues,” which are decisions, advice, and discussions reserved exclusively for partners and intentionally kept separate from family and friends. These may include topics like birth control, budget management, sexual preferences, or resolving arguments. Maintaining confidentiality within the marital relationship is crucial to prevent harmful intrusions from external sources.

Marriage, as a formal, legally recognized union between individuals, contrasts with cohabitation, which is an informal arrangement based on sharing a residence without the legal formalities. While monogamy remains the culturally preferred form of marriage in the U.S. and worldwide, allowing only one spouse at a time, cohabitation has become increasingly popular over the last 30 years. Cohabiting couples live differently from married couples in various aspects of daily life, and while many eventually marry, they often face a higher risk of divorce compared to couples who never cohabited.

In the United States, marriage is commonly associated with monogamy, where one person is married to only one partner at a time. However, in many countries and cultures worldwide, marriage takes various forms beyond monogamy. Polygamy, which involves being married to more than one person simultaneously, is accepted to different extents across the globe, with most polygamous societies concentrated in northern Africa and east Asia (OECD 2019).

Polygamy primarily involves a man being married to multiple women concurrently, rather than the reverse (Altman and Ginat 1996). Despite its acceptance in many societies, the actual practice of polygamy is not widespread. Even in regions where it’s prevalent, only around 11 percent of the population live in such arrangements, on average (Kramer 2020). Typically, these relationships involve older, affluent men with high social status (Altman and Ginat 1996). The average polygamous marriage consists of no more than three wives, with examples such as Negev Bedouin men in Israel often having two wives, although having up to four is acceptable (Griver 2008). Urbanization tends to decrease the prevalence of polygamy due to increased exposure to mass media, technology, and education (Altman and Ginat 1996).

In contrast, polygamy is illegal in the United States. According to a recent Gallup poll, 21 percent of respondents view polygamy as morally acceptable, representing a notable increase from previous polls. However, polygamy remains one of the least acceptable behaviors among those surveyed, ranking lower than consensual sex between teenagers but higher than a married person having an affair (Barosso et al. 2020). Engaging in marriage while still legally married to another person is termed bigamy and is considered a felony in most states.

Polyandry is a type of marriage that allows for more than one husband at the same time. Historically and presently, this practice is rare, but it has been documented in various cultures across the globe, including some Pacific Island cultures, Africa, Asia, Europe, and South America (Wikipedia 2024).

What if someone enters into multiple marriages and divorces over time? This phenomenon is known as serial monogamy or serial polygamy. It involves establishing intimate relationships through marriage or cohabitation that eventually end and are followed by new relationships, repeating the pattern. While polygamists have simultaneous multiple spouses, serial monogamists or polygamists have multiple spouses in a sequence of relationships. Millions of adults in the United States will experience serial marriages and divorces. Despite the risks associated with marriage, many individuals still desire to remarry, even after going through divorce or witnessing their parents’ unhealthy marriages.

Traditional gender roles have historically influenced power dynamics within marriages and families. Patriarchal families, where males hold more power and authority, have been prevalent throughout history, with rights and inheritances typically passing from fathers to sons. However, there is a growing trend towards egalitarian families, where power and authority are more evenly distributed between husbands and wives.

Marriage

Marriage, as legally registered by the state and recognized by the federal government, has evolved over centuries. While in the past, marriage rights were often dictated by fathers, clan or kinship leaders, religious leaders, and community members, today, the state or nation claims authority over marriage licenses and legal recognition. The legalization of same-sex marriage in the United States marked a significant shift in marriage laws, with the U.S. Supreme Court ruling in 2015 granting same-sex couples the right to marry nationwide (Cherlin 2010). This ruling sparked both celebration and controversy, reflecting the deep divide between liberal and conservative viewpoints in American society. Pew Research (2017) reports illustrate the widening gap between these two groups over time, emphasizing the increasing polarization of social issues including same-sex marriage.

The U.S. Census Bureau conducts yearly surveys called the Current Population Surveys, which provide insights into the makeup of the U.S. population. Table 4.2 displays the numbers and percentages of different family types in 2019 compared to 2011. It’s evident that married couples constituted the largest proportion of family types in both years. Marriage remains the most preferred marital status, encompassing various types such as first marriages, remarriages, heterosexual or same-sex marriages, as well as inter-racial or inter-ethnic marriages. The number and percentage of marriages increased from 2011 to 2019. The proportion of widowed individuals remained fairly constant, with minimal changes. On the other hand, the numbers of divorced and separated individuals increased, although not significantly in terms of percentages. There was also an increase in the number and percentage of never-married singles from 2011 to 2019. These changes in marital status composition reflect shifts in society as a whole.

Table 4.2. U.S. Family Types Numbers & Percentages 2019 and 2011

| Types | 2019 & 2011 Numbers in Millions | 2019 & 2011 Percentages |

|---|---|---|

| Married | 137 & (123.9) | 53% & (52%) |

| Widowed | 14.2 & (14.2) | 6% & (6%) |

| Divorced & Separated | 40.3 & (30.0) | 11% & (12.6%) |

| Never Married-Single | 85.2 & (75.8) | 32 % & (30%) |

Source: U.S. Census Bureau. 2023. “MS-1. Marital Status of the Population 15 Years Old and Over by Sex, Race and Hispanic Origin: 1950 to Present.” Retrieved March 27, 2024 (https://www.census.gov/data/tables/time-series/demo/families/marital.html).

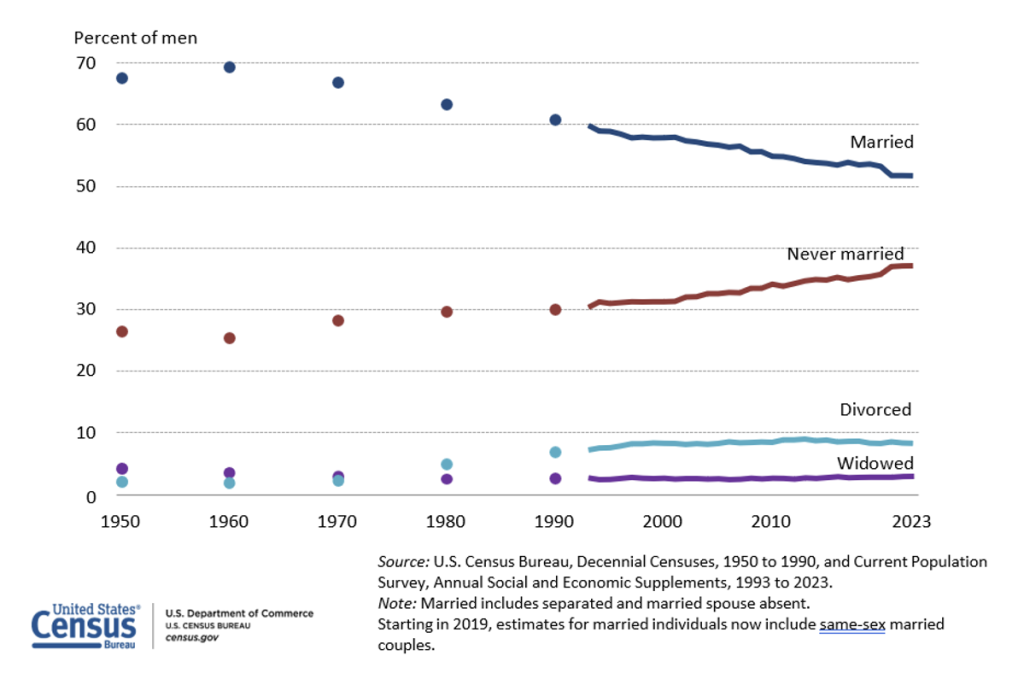

Analyzing U.S. Census data reveals changes in the proportions of marital status for both men and women from 1950 to 2019. Figure 4.3 illustrates the trend of percentages of marital status types for men during this period. Despite being the most common status, the proportion of married men declined from around 70% in 1960 to approximately 53% in 2019. Conversely, the percentage of never-married singles among men increased from about 26% in 1950 to around 36% in 2019. This trend indicates that more individuals from Generation Y and Z are postponing marriage in the United States.

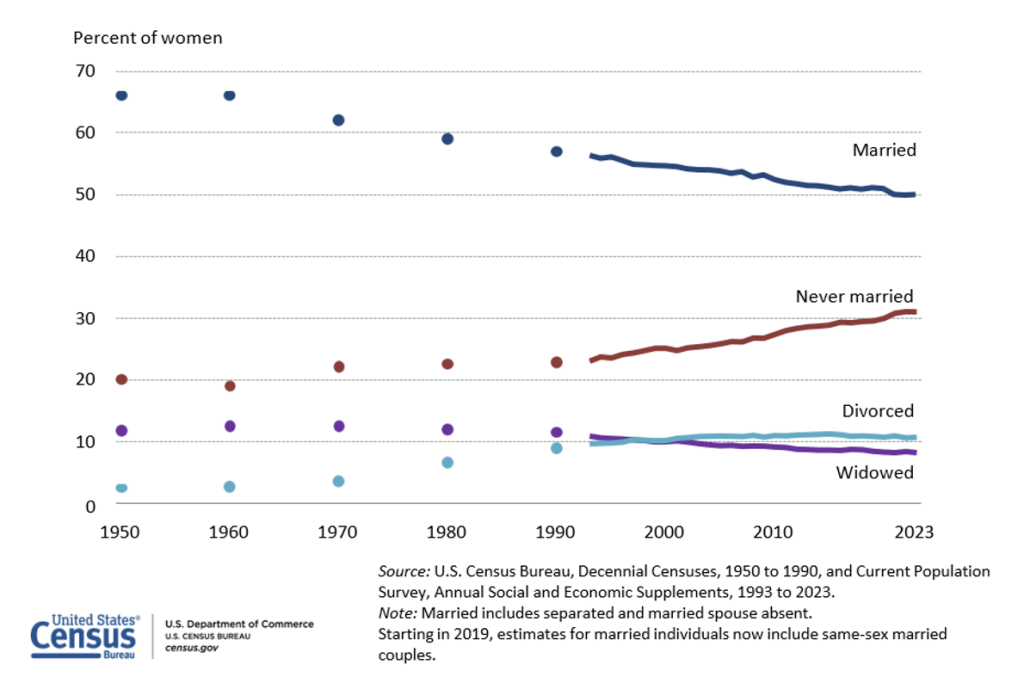

Similarly, Figure 4.4 displays the trend of percentages of marital status types for women from 1950 to 2019. Like men, married women remained the most common status, although it declined from approximately 68% in 1960 to about 51% in 2019. The proportion of never-married singles among women rose from about 20% in 1950 to around 30% in 2019, indicating a similar trend of delaying marriage among women, particularly among Generation Y and Z.

Can we explore why some marriages endure while others end in divorce? Robert and Jeanette Lauer, a husband-wife duo who extensively studied families, authored a book titled “Marriage and Family: The Quest for Intimacy” in 2009. Through their research, they examined the commitment and longevity of married couples, identifying 29 factors among couples who had been together for 15 years or more. Among these factors, both husbands and wives consistently ranked “My spouse is my best friend” and “I like my spouse as a person” as their top two factors. The Lauers also examined the level of commitment couples had toward their marriage, finding that they were dedicated to not only their own marriage but also the institution of marriage as a whole.

Figure 4.3. Men’s Percentage Marital Status Proportions 1950-2019

Source: Hammond, Ron, Paul Cheney, Raewyn Pearsey. 2021. Sociology of the Family. Ron J. Hammond & Paul W. Cheney. Retrieved March 27, 2024 (https://freesociologybooks.com/Sociology_Of_The_Family/09_Marriage_and_Other_Long-Term_Relationships.php).

Figure 4.4. Women’s Percentage Marital Status Proportions 1950-2019

Source: Hammond, Ron, Paul Cheney, Raewyn Pearsey. 2021. Sociology of the Family. Ron J. Hammond & Paul W. Cheney. Retrieved March 27, 2024 (https://freesociologybooks.com/Sociology_Of_The_Family/09_Marriage_and_Other_Long-Term_Relationships.php).

It’s common for marriages to encounter irreconcilable differences, and the key strategy to address them is negotiation, acceptance of differences, and maintaining a positive outlook on the marriage. While technically all married couples face a risk of divorce, this risk varies. Newly married couples, particularly within the first 10 years of marriage, undergo significant adjustments, especially in the initial 36 months. They must establish new boundaries and relationships, negotiate daily life routines, and get to know each other better. However, as couples stay together longer, their risk of divorce tends to decrease. In fact, most marriages in the U.S. endure for a long time.

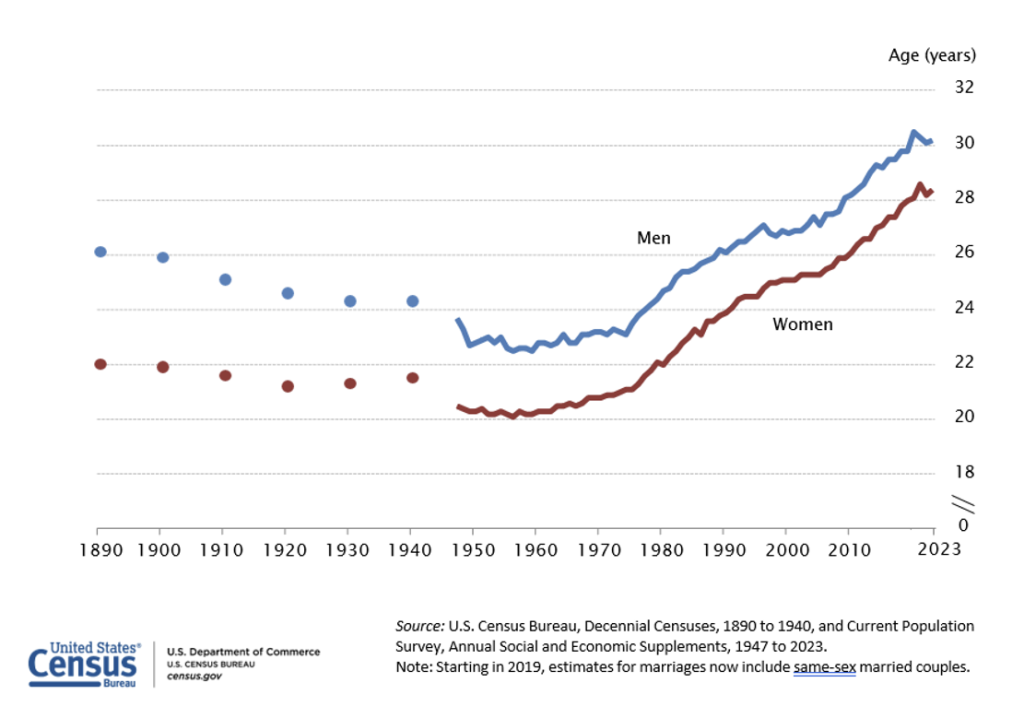

Individuals who marry during their teenage years, even as young as 17, 18, or 19, have notably higher rates of divorce. This might be attributed to the fact that individuals continue to undergo significant changes until around the age of 25-26, when they achieve full psychological maturity. Couples who marry in their teens often find themselves outgrowing each other, including changes in attraction due to evolving preferences. Data from the U.S. Census Bureau (2023) often reveals that individuals marrying in their teenage years have the highest rates of divorce. However, it’s worth noting that the divorce rate may be decreasing as people are waiting longer before getting married. Figure 4.5 from the U.S. Census show that the median age at marriage has risen over the years, reaching its highest recorded levels in 2019, with the median age being 29.0 for men and 28.6 for women in the United States.

Figure 4.5. U.S. Median Age at Marriage for Men and Women 1890 and 2019

Source: Hammond, Ron, Paul Cheney, Raewyn Pearsey. 2021. Sociology of the Family. Ron J. Hammond & Paul W. Cheney. Retrieved March 27, 2024 (https://freesociologybooks.com/Sociology_Of_The_Family/09_Marriage_and_Other_Long-Term_Relationships.php).

As mentioned earlier, most unmarried mothers eventually marry the biological father of their child. However, these marriages are more likely to end in divorce compared to marriages between non-pregnant newlyweds. The presence of children at the time of marriage is often linked to higher divorce rates. Family Scientists have adopted a concept from physics known as entropy, which essentially suggests that matter tends to deteriorate and simplify over time. For instance, if a new car is left neglected in a field, it will eventually decay and deteriorate. Similarly, an untended garden will be overrun by weeds and pests, yielding little to no crop.

Marital entropy applies this principle to marriages, suggesting that without proactive maintenance and improvements, marriages tend to deteriorate and break down. Couples who recognize that marriage isn’t always a constant state of bliss and understand that it requires effort are more likely to experience stability and strength in their relationship. They prioritize preventative measures, treating their marriage like a valuable possession that requires care and attention.

ANALYZING FAMILY STRUCTURES

Marriage Law

Conduct research and find an academic journal article about marriage law changes in the U.S.

- How has marriage law changed over the years?

- Describe the specific laws and changes that have transformed at the federal level.

- What influences or social movements have contributed to these changes?

“Marriage Trends & Benefits?” by Katie Conklin, Lemoore College is licensed under CC BY 4.0

Many individuals struggle to fully embrace their married status, mentally remaining open to the possibility of finding someone better than their current spouse. Norval Glenn argued in 1991 that for many, marriage is seen as a temporary arrangement while they keep an eye out for a better partner. This highlights the cultural values associated with the risk of divorce.

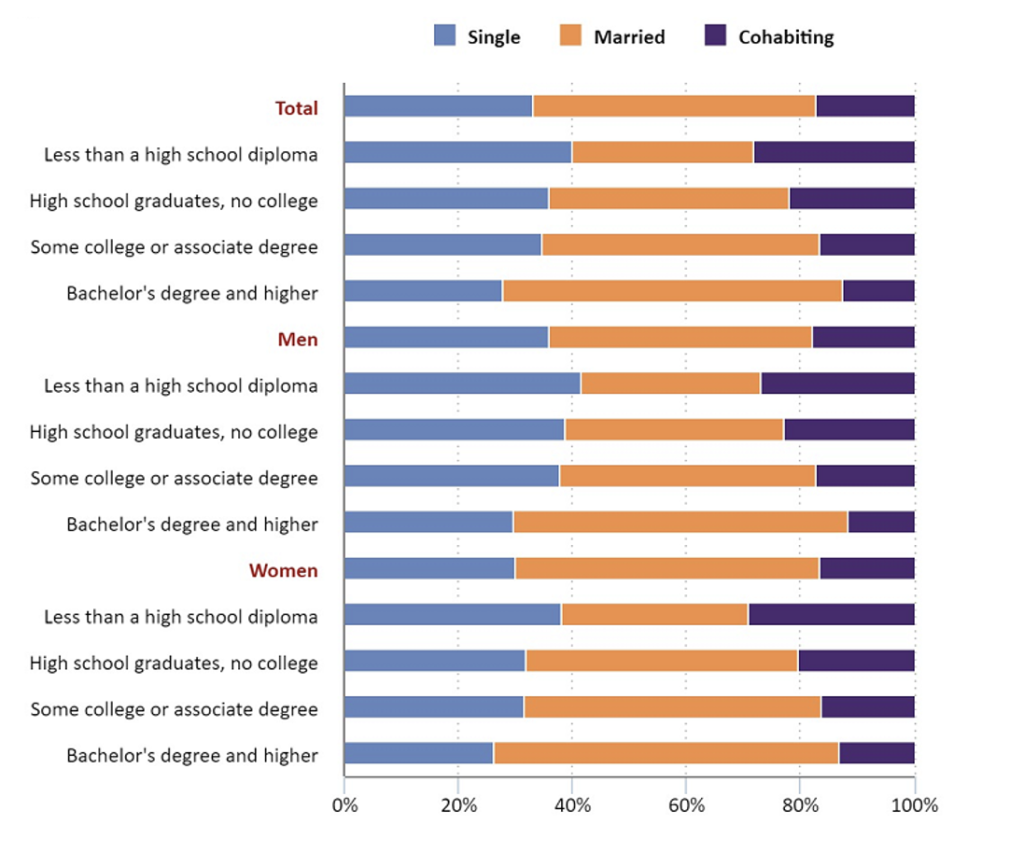

Figure 4.6 depicts a recent study conducted by the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (2020) examined the marital statuses of individuals born between 1980 and 1984, tracking them longitudinally until they reached the age of 33. The study revealed differences between men and women and among individuals with various levels of educational attainment. For example, by age 33, 50 percent of Americans born between 1980 and 1984 were married, while 17 percent were cohabiting, and 33 percent were single. Women were more likely than men to be married at age 33 and less likely to be single. Additionally, individuals with higher levels of education were more likely to be married and less likely to be cohabiting compared to those with lower levels of education. For instance, 60 percent of college graduates born between 1980 and 1984 were married by age 33.

It’s reasonable to expect that your marriage will likely be a positive and fulfilling relationship. However, the key is that the positivity and fulfillment of your marriage depend on the efforts you and your partner choose to invest in it. Gone are the days when traditional marriage was strongly supported by various social institutions like schools, religion, government, media, economy, education, and technology (although there’s debate about how supportive they ever truly were). Nowadays, the responsibility for nurturing a happy and fulfilling relationship falls almost entirely on the personal-level, continuous, proactive, and dedicated efforts of both partners. Despite this shift, the odds are still in your favor for a quality and lasting marriage.

You’ve probably come across commercials boasting about the success of matchmaking websites in pairing people together. While there have been some criticisms of online marital enhancement services, millions of individuals have found them useful. Additionally, there are self-help books, podcasts, seminars, and even websites dedicated to supporting married couples who want to be proactive and preventive in their relationship.

Figure 4.6. Partner Status At Age 33

Source: Hammond, Ron, Paul Cheney, Raewyn Pearsey. 2021. Sociology of the Family. Ron J. Hammond & Paul W. Cheney. Retrieved March 27, 2024 (https://freesociologybooks.com/Sociology_Of_The_Family/09_Marriage_and_Other_Long-Term_Relationships.php).

Taking the time to do your homework during the mate-selection process is crucial. As the saying goes, “An ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure,” and this certainly applies to selecting a partner. Understanding yourself, waiting until you’re in your twenties or older, and forming a strong friendship with your spouse can significantly impact your marital experience. It’s worth noting that most people don’t marry strangers; rather, they meet their partners through social networks such as work, campus, dorms, fraternities and sororities, friends of friends, and other connections.

Marriage remains popular among U.S. adults because it offers numerous rewards that unmarried individuals may not experience. Sociologist Linda Waite, along with Maggie Gallagher, co-authored a book titled “The Case For Marriage: Why Married People Are Happier, Healthier, and Better Off Financially” (2001), which highlights the benefits of marriage based on decades of research. Despite the controversy surrounding marriage, particularly regarding the legalization of same-sex marriage, the political efforts to recognize it underscore its significance as a rewarding and valued institution.

There is a wealth of studies and literature detailing the benefits of marriage for individuals. Table 4.3 outlines ten categories of these benefits for your consideration.

Table 4.3. Ten Benefits of Being Married

- Better physical and emotional health

- More wealth and income

- Positive social status

- More and safer sex

- Lifelong continuity of intimate relationships

- Safer circumstances for children

- Longer life expectancy

- Lower odds of being crime victims

- Enhanced legal and insurance rights and benefits (tax, medical, and inheritance)

- Higher self-reported happiness

Source: Hammond, Ron, Paul Cheney, Raewyn Pearsey. 2021. Sociology of the Family. Ron J. Hammond & Paul W. Cheney. Retrieved March 27, 2024 (https://freesociologybooks.com/Sociology_Of_The_Family/09_Marriage_and_Other_Long-Term_Relationships.php).

Consider that there’s no solid evidence proving that staying in a toxic marriage is better than being unmarried or never married. Rushing into marriage without careful consideration would be imprudent. Additionally, don’t assume that getting married means the end of your problems. A newlywed once exclaimed to her mother, “Now that I’m married, I’m at the end of all my problems.” Her mother wisely replied, “Which end, dear?” Remember, maintaining a fulfilling and satisfying marriage requires consistent, proactive, and timely effort from both partners. Ultimately, the responsibility for the quality of your marriage rests with you and your spouse.

ANALYZING FAMILY STRUCTURES

Marriage Trends & Benefits

Research shows a trend toward delaying marriage until later life. Consider the textbook illustrations that outline the potential benefits of marriage.

- Choose the three most desirable benefits of marriage you enjoy or look forward to.

- Categorize these benefits as either psychological, financial, or social, and share why think these are important to you culturally.

“Marriage Trends & Benefits?” by Katie Conklin, Lemoore College is licensed under CC BY 4.0

Cohabitation

Research on cohabitation has been extensive over the past three decades, particularly focusing on the likelihood of cohabiting couples eventually marrying. The findings consistently show that cohabitation and marriage are distinct, with economic factors playing a significant role in the transition from cohabitation to marriage.

There has been a noticeable increase in non-married cohabiting couples in recent decades, a trend that Pew Research Center reported as continuing in 2019. In 2017, Pew Research (2019) found that 50 percent of adults had ever married, while 59 percent had ever cohabited. This contrasts with their 2002 findings, where approximately 60 percent had ever married and only 54 percent had ever cohabited. Notably, Pew Research also reported that from 1995 to 2019, the percentage of adults living with an unmarried partner rose from 3% to 7%.

Moreover, Pew Research (2019) surveys revealed that a majority of U.S. adults, both cohabiting and married, expressed significant trust in their partner or spouse. However, married adults tended to express higher levels of trust compared to cohabiting adults regarding fidelity, acting in their best interest, honesty, and financial responsibility.

When asked about their reasons for cohabiting, respondents cited reasons such as love, companionship, the desire to make a formal commitment, financial practicality, the intention to have children someday, convenience, and wanting to test the relationship. The Pew Research Center (2019) found U.S. cohabitation rates between 1995 and 2018 have largely stabilized in recent years, showing no significant increase or decrease for most age groups.

In 2012, the U.S. Census Bureau revealed that there were approximately 7,845,000 million heterosexual couples living together and about 687,000 same-sex couples. However, Gallup (2024) reported a significant decline in same-sex cohabitation rates from 12.8 percent before the Supreme Court’s ruling on same-sex marriage (Obergefell v. Hodges, 26 June 2015) to only 6.6 percent in 2017. This decrease coincided with an increase in the number of same-sex couples legally married, rising from 7.9% before the ruling to 10.2% afterward (Jones 2017).

Studies have also examined the duration of first cohabitation relationships and their outcomes. Approximately 42 percent of cohabiting women transitioned to marriage within three years, while 32 percent remained together without marrying, and 27 percent ended their relationship (U.S. Census Bureau 2012).

Research by David Popenoe and others has highlighted the differences between cohabitation and marriage, emphasizing that cohabiting relationships tend to be less stable and less beneficial for children’s well-being compared to marriage (Popenoe 2009; Williams et al. 2008). Serial Cohabiters, individuals who have multiple cohabiting relationships over time, often face higher divorce risks if they eventually marry compared to those who never cohabit serially (Lichter and Qian 2008).

Despite the various forms of relationships, marriage remains the most sought-after and preferred structure for most adults, although cohabitation continues to increase as a choice for many. It is essential to recognize that same-sex marriage, which has been legal in the U.S. for about five years, may have distinct patterns and challenges compared to heterosexual marriage. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s principles of social reform, emphasizing compassion and love for all, including those different from oneself, can provide valuable guidance in navigating interpersonal relationships and promoting a better quality of life for all individuals (Frankl 2006).