5.2 Family Structures

As we discussed in Module 1, family structures refer to the arrangement of individuals in a household who are connected either by blood relations or legal bonds. Typically, this includes households with at least one child below the age of 18. Different types of family structures exist: two-parent households, single-parent households, and situations where children live with neither parent, such as with grandparents or in foster care.

The U.S. Census Bureau (2019) defines various family structures:

- Nuclear family: This consists of a child living with two married biological parents along with any full siblings.

- Cohabiting families: In these families, a child’s parent lives with at least one unrelated adult of the opposite sex. This adult may or may not be the child’s biological parent.

- Same-sex cohabiting/married families: A child’s parent lives with at least one unrelated adult of the same sex. Again, this adult may or may not be the child’s biological parent.

- Stepfamilies or blended families: These are formed through remarriage, resulting in children living with one or no biologically related parents. The presence of a stepparent, stepsibling, or half-sibling indicates a blended family.

- Children with grandparents: An arrangement where grandparents assume primary caregiving responsibilities, often due to circumstances such as parental incapacity, economic needs, or family tradition, providing stability and continuity but also facing financial and physical challenges.

Family Processes & Functions

Family processes refer to how families operate internally to handle cognitive, social, and emotional situations. These include how families adjust, talk to each other, deal with challenges, solve problems, raise children, make choices, organize activities, and take charge (Pasley and Petren 2015). Many family functions overlap with tasks, objectives, and duties of parenting. However, it’s crucial to grasp how these functions and parenting responsibilities influence each other. Here’s a list of family functions that are somewhat universal, meaning most families worldwide share some of these:

- Economic support: This involves providing essentials like food, shelter, and clothing.

- Emotional support: Families offer love, comfort, closeness, companionship, care, and a sense of belonging.

- Socialization of children: This includes raising and guiding children to thrive within their society.

- Control of sexuality: Families establish and regulate when and with whom sexual activity, including marriage, occurs.

- Procreation: Families contribute to the continuation of society and the production of offspring.

- Ascribed status: Families impart social identities such as social class, race, ethnicity, kinship, and religion (Hammond et al. 2021).

Influences of parenting on development

Parenting is a complicated process where parents and children affect each other. Parents behave the way they do for various reasons, and researchers are still studying the many factors that influence parenting. Some suggested influences on parental behavior include traits of the parents themselves, characteristics of the child, and surrounding environmental and cultural factors (Belsky1984; Demick 1999).

Parents bring their own unique characteristics and qualities into the parenting relationship, which shape how they make decisions as parents. These traits include factors such as their age, gender identity, personality, personal history, beliefs, knowledge about parenting and child development, as well as their mental and physical well-being. Additionally, parents’ personalities play a significant role in their parenting behaviors. For instance, parents who are agreeable, conscientious, and outgoing tend to be warmer and provide more structure for their children. Conversely, parents who exhibit less anxiety and negativity are more supportive of their children’s autonomy compared to those who are more anxious and less agreeable (Prinzie et al. 2009). Parents with these personality traits seem better equipped to respond positively to their children and maintain a consistent and structured environment for them.

Moreover, parents’ own experiences during their upbringing, known as their developmental histories, can also influence their parenting approaches. They may adopt parenting practices learned from their own parents, with fathers who received monitoring, consistent discipline, and warmth during their childhood being more likely to employ these constructive parenting techniques with their own children (Kerr et al. 2009). Unfortunately, patterns of negative parenting and ineffective discipline can also be passed down from one generation to the next. However, parents who were unhappy with their own caregivers’ methods may be more inclined to alter their own parenting strategies when they become parents themselves.

Parenting involves a two-way exchange. Not only do parents and caregivers influence their children, but children also have an impact on their parents or primary caregivers (Diener 2024). Certain characteristics of children, like their gender identity, birth order, temperament, and health status, can affect how parents raise them and the roles they assume in caregiving. For instance, having an infant with an easy temperament may make caregivers feel more effective because they can easily soothe the child and elicit positive responses like smiling and cooing. Conversely, caring for a cranky or fussy infant may lead to fewer positive interactions and make parents feel less effective in their role (Eisenberg et al. 2008).

Over time, parents of more difficult children may become stricter and less patient with their parenting (Clark et al. 2000; Kiff et al. 2011). Studies have shown that parents of fussy or difficult children often report lower satisfaction in their relationships and face greater challenges in balancing work and family responsibilities (Hyde et al. 2004). Thus, a child’s temperament is one of the factors influencing how caregivers interact with them.

Another factor is the child’s gender identity. Some parents assign different household chores to their children based on their gender identity. For example, older research indicates that girls are typically tasked with caring for younger siblings and doing household chores, while boys are more often assigned outdoor chores like mowing the lawn (Grusec et al. 1996). Additionally, studies have found that parents communicate differently with their children based on their gender identity, such as providing more scientific explanations to sons and using more emotional language with daughters (Crowley et al. 2001).

The relationship between parents and children doesn’t happen in a vacuum. Various sociocultural factors, such as economic challenges, religious beliefs, political climate, neighborhood environments, school settings, and social support networks, can also shape parenting behaviors. When parents face economic difficulties, they may experience heightened frustration, depression, or sadness, which can impact their ability to parent effectively (Conger and Conger 2004). Additionally, culture plays a significant role in shaping parenting practices. While all parents aim to equip their children with skills to succeed in their community, the specific skills valued can differ greatly across cultures (Tamis-LeMonda et al. 2007). For instance, some parents may prioritize independence and individual achievements, while others emphasize maintaining harmonious relationships and being part of a strong social network. These cultural differences in parental goals can also be influenced by factors such as immigration status.

Moreover, contextual factors like neighborhood safety, school environment, and social connections can also affect parenting, even when both the child and parent are not directly involved in these settings (Bronfenbrenner 1979). For example, research has shown that Latina mothers who perceive their neighborhood as unsafe may exhibit less warmth towards their children, likely due to the added stress associated with living in a threatening environment (Umaña-Taylor et al. 2011).

Parental Investment & Functions

The growth of an individual involves actively adapting within their social and economic environment. For instance, the level of closeness and positive attachment in the parent-infant bond, often with the mother, and the support provided by parents during early childhood, including nutrition, shape a child’s experiences. These experiences influence the development of individual variations in how the brain responds to stress, impacting memory, attention, and emotions. From an evolutionary perspective, this process enables offspring to adjust gene expression patterns. These adjustments contribute to the formation and functioning of neural circuits and molecular pathways, supporting three main aspects: (1) biological defensive systems for survival (e.g., stress resilience), (2) reproductive success to promote establishment and persistence in the present environment, and (3) adequate parenting in the next generation (Bradshaw 1965).

Parenting is the essential process of nurturing, guiding, and preparing children for adulthood. It’s a universal experience found in every culture throughout history. When babies are born, they’re not automatically fully equipped for society. They need to learn social and emotional skills through interactions with family and friends as they grow.

Parents serve various crucial roles in society. They provide care, protection, and guidance to their children from birth through adulthood. They also play a vital role in socializing their children, teaching them the norms, values, and behaviors of their community. Socialization begins early in a child’s life with parents, family, and friends shaping their understanding of the world. This primary socialization continues until the child starts school, influencing how they interact and meet society’s expectations.

Parents act as teachers throughout their children’s lives, imparting skills and values essential for success. They also serve as guardians, ensuring their children’s well-being and making important decisions on their behalf. Additionally, parents act as mediators between their children and the wider community, advocating for their needs and defending them when necessary. They play a crucial role in ensuring their children have the best opportunities for growth and development.

Surprisingly, there has been a decline in the number of babies born per mother in recent years in the U.S. This decline is evident across various demographic indicators. For instance, the General Fertility Rate (GFR), which measures the number of births per 1,000 women aged 15-44, has been decreasing. Additionally, the Completed Fertility Rate, representing the total number of children a woman has in her lifetime, has also seen a decline. A May 2019 Pew Research Report highlights this trend, indicating that U.S. fertility has reached an all-time low according to three significant measures spanning from 1950 to 2018.

In Module 1 of our book, we explored the concept of “instability” in children’s lives, which reveals a significant aspect of parenting in the United States that warrants further discussion. Traditionally, most couples refrained from sexual intercourse until marriage due to limited access to effective birth control, resulting in pregnancies often following unprotected sexual encounters. Andrew Cherlin (2010) highlights how Baby Boomers shaped a cultural shift by extending the pattern of sexual relations beyond marriage to include premarital, extramarital, post-divorce, and post-remarriage scenarios.

Childhood instability refers to frequent changes in household and parental relationship statuses during a child’s first 18 years. This can encompass various scenarios, including children born to single, cohabiting, or married parents, experiencing parental divorce, separation, or remarriage, or encountering parental challenges like incarceration or addiction, and even entering the foster care system.

Cherlin’s book offers in-depth analysis and research on shifts in U.S. family structures over the past century. He argues that a transition in U.S. individualism has shifted focus from collective family units to individual pursuits of self-fulfillment. Cherlin illustrates how this shift in values, evident from Baby Boomers to Generations X, Y, and Z, clashes with the traditional emphasis on marriage, influencing trends in family dynamics observed both domestically and globally.

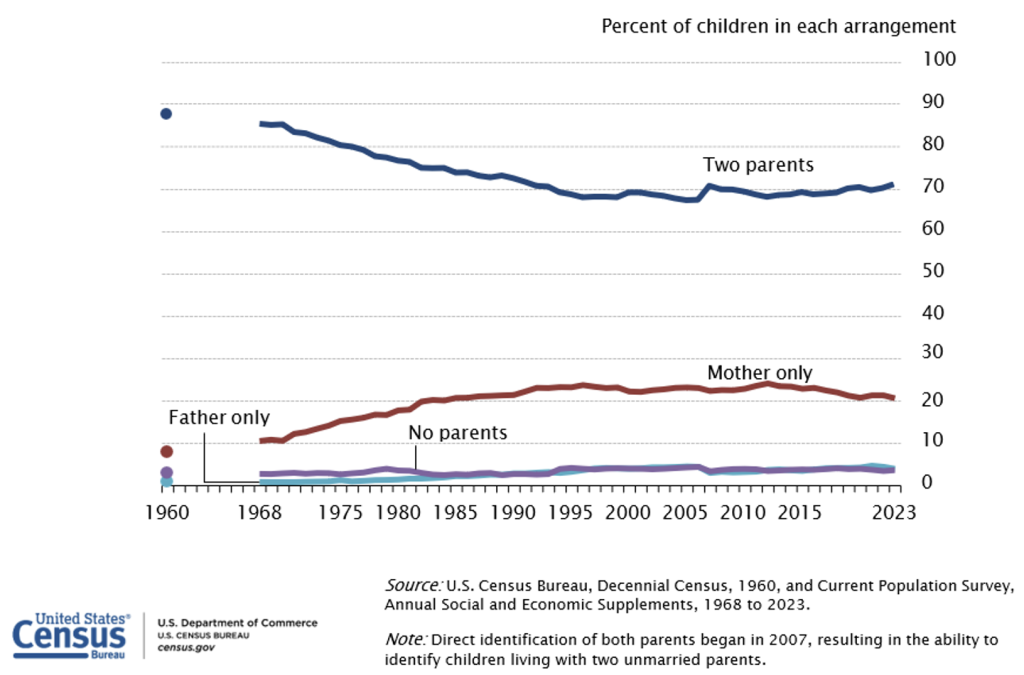

Supported by robust research data, Cherlin demonstrates the significant decline in the percentage of children living with two parents (married or cohabiting) from 88 percent in 1960 to about 70 percent in 2019, as depicted in Figure 5.1 from the U.S. Census Bureau. Furthermore, in 2019, many children residing in two-parent households experience childhood instability even before any remarriage occurs, reflecting broader societal shifts known as the “Marriage Go Round.”

From a developmental standpoint, parents aim to nurture children into becoming independent, competent, and self-reliant adults who can thrive both within and outside their family circles. Typically, children start out with low levels of independence, which gradually increase during adolescence. This period is marked by a process known as individuation, where teenagers strive to establish their own identities and reduce their reliance on others, particularly their parents. The journey toward independence begins as early as the second year of life, with children gradually mastering self-care tasks as they grow older. Table 5.1 provides an overview of the stages of dependence and a child’s ability to care for others across different life stages.

Parenting from birth to age 18 demands a deep understanding of how children grow and evolve from infancy to young adulthood. Psychologists like Jean Piaget, Sigmund Freud, Eric Erickson, and sociologists such as John B. Watson, George Herbert Mead, and Charles Cooley have spent years studying child development, shaping critical research in this field. While we can’t delve into all their theories, let’s explore some key concepts that can aid parents in their journey.

Figure 5.1. Living Arrangements of Children: 1960 to Present

From birth to age 5, children have limited independence and rely heavily on adult caregivers for survival. Although they crave autonomy, their cognitive and physical abilities are still developing, making them reliant on adults for most tasks. However, through play, they begin to exhibit nurturing behaviors.

Between ages 6 and 12, children experience physical growth and emotional and intellectual development. They become more self-sufficient and can assist with tasks, but their ability to nurture is limited due to their still-developing reasoning skills. During adolescence (ages 13 to 18), teens undergo significant cognitive growth, engaging in abstract reasoning and emotional complexity. While they gain some independence and can offer care to others, their emotional volatility can pose challenges.

Parenting strategies must adapt to each age group’s unique needs and developmental stage, recognizing that individual children vary in their response to different approaches. As children transition into young adulthood, they navigate a balance between independence and reliance on their parents for guidance and support. Despite seeking autonomy, they still lean on their parents for advice, resources, and emotional support as they prepare for adult roles. When young adults become parents themselves, they join a legacy of caregivers who have aimed to raise their children effectively. They often turn to their own parents for guidance, benefiting from the wisdom and experience they offer. Studies suggest that young parents thrive with support from friends and family, highlighting the importance of a supportive network in nurturing their own children.

Table 5.1. Children’s Dependence and Their Ability to Nurture Others

| Stage | Independence Levels | Ability to Nurture |

|---|---|---|

| Newborn | None | None |

| 1-5 | Very Low | Very Little |

| 6-12 | Functional | Low |

| 13-18 | Moderate | Moderate |

| 19-24 | Increasingly higher | Increasingly higher |

| Parenthood | High but needs support | High but needs support |

Source: Hammond, Ron, Paul Cheney, Raewyn Pearsey. 2021. Sociology of the Family. Ron J. Hammond & Paul W. Cheney. Retrieved March 27, 2024 (https://freesociologybooks.com/Sociology_Of_The_Family/09_Marriage_and_Other_Long-Term_Relationships.php).

Balancing control and freedom

Given the wide range of development and growth among children, how can parents effectively fulfill their parenting duties? The solution lies in identifying a few key parenting paradigms and approaches. These approaches stem from both classical and modern parenting research.

Many families have a tradition of overcoming past traumas, addictions, heartaches, and tragedies that have shaped their upbringing. In this model, two key strategies are emphasized: individuation and avoiding enmeshment with children.

Individuation is the process by which children establish their own identities, recognizing themselves as unique individuals with distinct tastes, desires, talents, and values. Individuated children can differentiate between the consequences of their own actions and those of others. For example, an individuated child may feel embarrassed by a drug-addicted sibling but understands that the sibling’s choices are separate from the family’s identity. Individuated children also develop the independence to pursue their own paths and assume adult responsibilities.

Conversely, enmeshment occurs when parents and children intertwine their identities so closely that they struggle to function independently. Enmeshed relationships lack clear boundaries and foster unhealthy dependence, resembling overcooked spaghetti noodles melded into a single mass. For instance, parents may exert control over aspects of their adult child’s life, such as finances or marital decisions.

Parents who prioritize their children’s autonomy foster individuation and minimize enmeshment. By allowing children to make their own choices, from selecting clothing to setting personal boundaries, parents encourage independence and self-sufficiency. Studies suggest that providing both support and guidance yields the most positive outcomes for children. While support nurtures individual growth and societal contribution, guidance ensures that children learn to respect limits and accept responsibility for their actions. Ultimately, a balanced approach of support and control empowers children to navigate adulthood successfully.

Baby Boomers, born between 1946 and 1964, were raised by parents who adhered to strict “spare the rod, spoil the child” or “my house, my rules” approaches to parenting. These parents maintained firm control over their children, leaving little room for negotiation or input. Interestingly, the countercultural movement of the Hippie era emerged from this generation, often as a reaction to the authoritarian parenting style they experienced. Children tend to rebel against strict authority figures, making it easier to rebel against rigid parents than those who adopt a more democratic approach. When parents strike a balance between authority and cooperation, rebellion tends to decrease.

In the middle of the parenting spectrum lies a healthy zone where control is shared between parents and children. Healthy parents value their children’s input and involve them in decision-making processes, such as planning vacations or home renovations. They have the confidence to relinquish some control to their children while maintaining overall authority.

Many Baby Boomers, aiming to avoid replicating the harshness of their own upbringing, erred on the side of under-control in parenting. They allowed their children considerable freedom to find their own paths, sometimes to the detriment of the children. Some children of under-controlling parents ended up making serious mistakes in life, perhaps seeking attention or boundaries that were lacking at home. Research suggests that children raised by parents who strike a balance between support and moderate control are more likely to grow into responsible adults who contribute positively to society.

While it’s essential for parents to respect their children’s autonomy, it’s equally important for them to assert authority and provide guidance. Parenting styles that combine authority with opportunities for children to negotiate their own decisions foster healthy development amidst the myriad distractions and choices children face daily.

Many parents grew up facing challenges like emotional, financial, or social struggles, and in some cases, abuse or addiction. Some were forced into caregiving roles at a young age, missing out on their own childhood experiences. As a result, they may enter parenthood hoping to fulfill the needs they missed out on as children themselves, creating a cycle where caregiving is passed down through generations.

Breaking this cycle of counter-caregiving is crucial. Even if parents didn’t have supportive or controlling upbringing and have unmet childhood needs, their primary task is to provide for and nurture their own children and grandchildren. Seeking professional counseling can help parents recognize and address these issues, allowing them to heal and prevent unhealthy patterns from continuing. An apt metaphor for this situation is that “water flows downhill.” Regardless of their upbringing, parents must focus on filling the cup of the next generation’s needs. They should avoid relying on younger family members to fulfill their own needs, as this perpetuates an unhealthy cycle. It’s a simple yet effective way to understand the importance of breaking harmful patterns in parenting.

Behaviorism

Behaviorism is a theory of learning that suggests children repeat behaviors that bring rewards while avoiding those that lead to punishment. This approach is particularly useful when parenting younger children who may not yet grasp complex reasoning. For instance, a four-year-old may not fully comprehend the dangers of playing near a busy street despite warnings. In such cases, parents often resort to methods like time-outs to discourage risky behavior. While spanking was once a common form of discipline, studies show that non-spanking approaches can be just as effective. However, despite changing attitudes towards spanking, it still persists in some families, often behind closed doors.

Understanding what motivates your child is key to effective discipline. Some children respond well to verbal cues or disappointed looks, while others may require more tangible rewards or privileges. Each child’s preferences vary, so it’s important for parents to tailor their approach accordingly. For example, Mrs. Peterson, a kindergarten teacher, found that a single Tootsie Pop could be more effective than multiple spankings or scoldings. By identifying what motivates your child, whether it’s praise, privileges, or treats, you can reinforce positive behaviors and discourage negative ones.

Effective discipline involves connecting the consequence to the behavior. For instance, if a teenager breaks curfew, grounding them from social activities aligns with the natural consequence of their actions. Similarly, rewarding good behavior in public settings reinforces positive conduct.

Ultimately, the goal is to teach children to understand the consequences of their actions and to encourage positive behavior through appropriate rewards and consequences.

Table 5.2. Examples of Rewards and Punishments for Children

| Possible Rewards | Possible Punishments |

|---|---|

| Verbal approval | Verbal disapproval |

| Verbal praise | Verbal reprimands |

| Sweets | Time out (in chair, bedroom, corner) |

| Playtime, friend time | Groundings (from friends, toys, driving, etc.) |

| Special time with parents | Chores |

| Access to toys | No access to toys |

| Money/allowance | Suspended allowance, small monetary fines |

| Permission | Denial of opportunities |

| Driving, outings with friends | Withdrawal of privileges |

Source: Hammond, Ron, Paul Cheney, Raewyn Pearsey. 2021. Sociology of the Family. Ron J. Hammond & Paul W. Cheney. Retrieved March 27, 2024 (https://freesociologybooks.com/Sociology_Of_The_Family/09_Marriage_and_Other_Long-Term_Relationships.php).

The Cognitive Model

One discovery about behaviorism is that it’s most effective with younger children and should be supplemented with a cognitive approach as children grow older. The Cognitive Model of parenting relies on reasoning and explanation to persuade children to understand why certain behaviors are important. As children mature past the age of 7, they develop greater reasoning skills and can engage in more complex discussions.

The Cognitive Model offers a different approach for parents who feel uncomfortable with behaviorism, which they may perceive as bribery or coercion. However, it’s important to recognize that when parents use rewards and punishments, their goal is typically to support the child’s development and growth rather than selfish gain. It’s crucial to understand that children, like adults, are motivated by rewards and seek to avoid punishment. For example, if a driver consistently speeds without consequences, they’re likely to continue speeding. However, if they face the threat of losing their license after accumulating points, they may slow down to avoid the punishment.

The next stage in the parenting model is to gradually introduce children to responsibility and prepare them for adulthood. While parents may want to shield their children from failure, experiencing setbacks can be valuable learning experiences. Some parenting styles encourage children to learn from their own efforts, while others may involve more intervention in the learning process.

While no parenting approach works perfectly for every child, behaviorism and cognitive strategies can be effective, even when emotions override reasoning, especially with teenagers. These methods provide structure and guidance, even in emotionally charged situations.

Types of Parenting

Rescue parents are always stepping in to solve their children’s problems. They might constantly assist with homework, ask teachers for special treatment, or shield their child from any possibility of failure. By doing so, they unintentionally erode their child’s confidence and independence, making them feel incapable of handling things on their own. These children often grow up dependent and lack a sense of individuality.

Dominating parents exert excessive control over their children. They demand obedience and impose strict rules, often dictating their child’s behavior, friendships, and activities. They may resort to humiliation or shame to enforce compliance, creating a dynamic where the child feels trapped and reliant on the parent’s authority.

Mentoring parents, on the other hand, engage in more collaborative parenting. They allow their children to make minor decisions like clothing choices or hobbies while establishing clear guidelines for important matters like dating or technology use. They involve their children in decision-making and offer choices within reasonable boundaries, fostering a sense of autonomy and responsibility. For instance, they might negotiate shared expenses for a car or explain the importance of sun protection while giving their child a choice in clothing options.

Parents often discover that even young children can contribute to household chores and tasks. When chores are presented as positive and rewarding activities, children can learn to assist their parents with housework and yard work. These practical skills are highly valuable in today’s world, as employers often struggle to find teenagers and young adults with experience in fulfilling assigned tasks effectively.

Working together on these everyday tasks can strengthen the bond between parents and children, fostering emotional connections that may not develop when family members are simply engaged in passive activities like watching TV or playing on the computer. With more women participating in the workforce, there are increased opportunities for men and children to engage in house and yard work together. This collaborative approach to chores can be both a bonding experience and an opportunity for personal growth for both parents and children.

When we ask scholars about their childhood chores, and most commonly, they mention tasks like cleaning their rooms or helping in the kitchen. However, occasionally, students from farming backgrounds share stories of more demanding and complex work they did from a young age, highlighting the challenges and dangers associated with farming for children. Many students also work part-time to support themselves through college, and those who have developed strong work ethics and the ability to follow through on tasks tend to have more positive work experiences overall.

Parents aiming to raise their children to become responsible co-adults should understand what it means to be a co-adult child. Co-adulthood refers to the stage children reach when they are independent, capable of shouldering responsibilities and roles, and confident in their own emerging adult identities. On the flip side, dependent adult children, often enmeshed with their parents and family members, represent the opposite of co-adulthood.

A co-adult child is independent, but this independence doesn’t negate the need for support and guidance. In fact, research on college-aged young adults indicates that many continue to rely on their parents well into their mid to late twenties. Psychologists suggest that the human brain fully matures around this age range in young adulthood.

There’s an important aspect of parenting often overlooked: children also play a role in shaping their parents. It’s amusing to reflect on how my wife and I, as newlyweds, debated over whether to save up for a pickup truck or a Ford Mustang. But when we learned we were expecting our first child, we found ourselves browsing minivans at a Dodge dealership. It was a surprising shift in our preferences driven by the anticipation of becoming parents.

The arrival of a newborn brings about significant changes for parents. Suddenly, there are constant demands to be met round the clock, every day of the year. While parents provide the essentials like bottles, diapers, and toys, it’s the baby who dictates the feeding preferences and sleep schedule, especially in those initial months. Babies condition parents to respond to their needs, teaching them how to hold, play, and interact based on the baby’s cues.

Of course, parents also play a role in shaping the child’s behavior. But babies effortlessly establish the rules of the caregiving dynamic by expressing happiness through smiles and giggles, or dissatisfaction through tears and cries. This dynamic of reward and punishment guides parents in understanding and meeting their child’s needs.

This reciprocal socialization process isn’t deliberate at first; it’s a natural survival instinct. While parents bring their own upbringing, societal expectations, and expert advice into parenting, it’s crucial for them to consider how their actions shape their child’s sense of self-worth.

Self-worth & shame

Self-worth refers to how a child feels about their own strengths and weaknesses, as well as their value as an individual. While sociologists once emphasized the importance of self-esteem, today the focus is more on teaching children to appreciate their uniqueness and understand that nobody is perfect. Parents play a crucial role in instilling this balanced sense of self-worth in their children.

One harmful message parents can inadvertently send to their children is shame, which makes them feel worthless or flawed at a fundamental level. Unfortunately, many parents perpetuate shame-based parenting, which can lead to negative outcomes in children. Shame lies at the root of many addictions, as individuals who view themselves as permanently flawed are more prone to addictive behaviors. Unlike guilt, which involves remorse for specific actions, shame instills a pervasive sense of worthlessness. Previous generations often used shame as a tool for control, but parents today can break this cycle by fostering healthy self-worth in their children.

By avoiding shame and instead teaching children to learn from failures and mistakes, parents empower their children to embrace their uniqueness and value as individuals. This process of building healthy self-worth involves balancing strengths and weaknesses and learning from feedback and experiences. As children grow into adulthood, they carry this positive self-evaluation with them, enabling them to navigate life’s challenges with confidence.

As parents, your views on self-worth directly influence your children. It’s important to consistently express value and support to them, especially during times of disappointment. Encourage them to set reasonable goals and to view their efforts objectively, recognizing their strengths and weaknesses.