5.4 Technology & Families

As scholars studying families, we start by understanding what a family is, how it works, how family members interact, and how families fit into society. Then, we look at how technology, like phones and computers, is used by families to communicate and manage their lives. Technology helps family members talk to each other and take care of family responsibilities. This section looks at important ideas about families and includes new ideas about how technology affects them. Finally, we talk about two models that mix old ideas about families with the ways technology is used today.

In our discussion about how technology impacts our lives, it’s important that we all have a common understanding of what we mean when we talk about families — it’s a group of two or more people who are connected to each other, share similar values, and are committed to each other. They also share things like intimacy, resources, decision-making, and responsibilities.

Now, let’s think about what families actually do. It might seem strange to question this since we all have experience being part of a family, even if our family situations have changed over time. Families are such a natural part of society that we often take their functions for granted. However, asking about their function helps us understand how families work and how they’re influenced by technology.

Families serve different functions: they support each other as a group, take care of individual members, and contribute to society as a whole, including its culture. For instance, one common function is providing emotional support and taking care of each other’s physical, mental, social, and sometimes spiritual well-being. Families also have a broader role in society by raising children and passing on cultural beliefs from one generation to the next, which helps maintain the well-being of their members in various aspects of life.

When we study families, it’s crucial to see them as part of a larger picture, connected to the world around them. This is where the idea of families as open systems comes in. Think of a family like a living organism, where each member is connected and influenced by the others, as well as by outside factors. This perspective, called family systems theory, sees families as ongoing systems made up of interconnected members.

One important aspect of this theory is that the whole family is more than just the sum of its parts. Each family has its own unique qualities, strengths, and weaknesses. It’s like a dynamic puzzle where information is constantly being shared through communication, affecting everyone involved.

Olson’s circumplex model further explores how families operate through communication, closeness, and adaptability. Communication in families comes in many forms like talking, texting, or even just body language. How each person communicates and understands messages can vary, which can impact family dynamics. Closeness, or cohesion, is another key aspect. It’s about finding the right balance between independence and togetherness within the family. Families need to be close enough to support each other but not so close that individual members feel suffocated.

In simple terms, families can be like either open or closed systems. An open family system is like a sponge—it’s open to new experiences, it grows, and it changes over time. On the other hand, a closed family system is more like a sealed box—it avoids change and prefers to stick with the way things are.

Conflict is a natural part of family life, but what really matters is how families handle it. Healthy families are flexible—they can adapt to change and work through conflicts while still staying strong. When faced with something like a family member coming out as gay, an open family system accepts and supports them, adjusting to this new understanding of their identity. In contrast, a closed family system might struggle to accept anything outside of what they consider “normal,” leading to a lack of communication and acceptance within the family.

Technology is another area where flexibility is important for families. An open family embraces technology and finds ways to use it that benefit everyone. But a closed family might resist using technology, seeing it as unnecessary or even harmful. Kevin Kelly talked about this in a podcast in 2018, using the example of the Amish community, who carefully decide whether to adopt new technologies like smartphones. They don’t reject innovation outright but instead test it to see if it fits with their values and benefits the whole community.

Flexibility isn’t just about big changes—it’s also about making small adjustments every day. Whether it’s negotiating screen time with a teenager or dealing with a major crisis like a natural disaster, families need to be flexible. This might mean showing compassion, communicating openly, or reorganizing responsibilities and resources to adapt to new situations.

In simpler terms, families don’t exist in a bubble—they’re influenced by the world around them, including their social environment, beliefs, and extended family. Social systems, like neighborhoods and schools, shape how families interact with others on a daily basis. Belief systems, such as traditions and values, guide how families live and what they aim for. Extended family members can also play a big role, passing on cultural norms and providing various types of support, which can be both helpful and sometimes stressful.

Families don’t just react to outside influences—they also affect each other within the family unit. As they adapt to changes, they find a balance, much like how our bodies maintain stability when faced with stress. Families, being a close part of an individual’s life, play a big role in shaping who they are and how they grow. Despite facing similar influences, each family responds in its own way. Factors like where they live, the time period they’re in, and the resources available to them all play a part in shaping their experiences and well-being.

Patterns of communication

Family communication is how families connect and stay close. It’s not just about talking—it’s also about how families interact and share information through both words and actions, like gestures or expressions. Families also show love and care through traditions like celebrating birthdays or cultural holidays, which can be unique to each family. Every family is different, and one way they vary is in how they communicate. For example, some families talk a lot about various topics, while others might not talk as much and have more diverse opinions. Some families are open to outside influences, while others prefer to stick to their own ways.

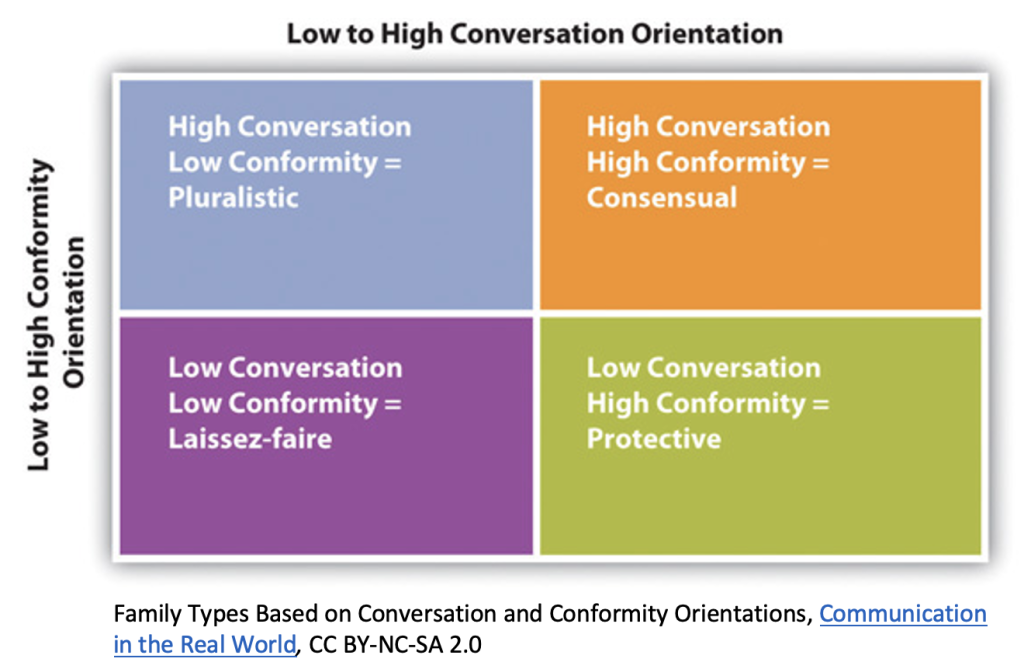

Researchers Koerner and Fitzpatrick (2006) have a theory about family communication that looks at two main things: conversation and conformity. Figure 5.2 describes conversation is about what families talk about, while conformity is about how much they stick to certain values or beliefs. Families with low conversation might not talk much and might have limited topics, while those with low conformity might have a wide range of opinions and interests. Families with high conformity might be more protective, while those with high conversation might have more diverse viewpoints. In a nutshell, how families communicate can create different climates within the family, from protective to open and diverse, depending on how much they talk and how much they conform to certain ideas.

Figure 5.2. Family Types Based on Conversation and Conformity Orientations

Source: Walker, Susan K. 2022. Critical Perspectives on Technology and the Family. University of Minnesota Libraries Publishing. Retrieved April 1, 2024 (https://open.lib.umn.edu/technologyfamily/).

Social networks of families

Social network theory comes from studying how people interact and share resources across different relationships. These networks aren’t confined to specific institutions but are shaped by the connections between individuals. They’re made up of links between people, and factors like the size and shape of the network, as well as how closely connected people are, play a big role. Social networks have power—they can influence how individuals and groups behave. The structure of these networks determines how information and influence flow within them, whether it’s between individuals or across multiple connections, creating a bigger impact.

Moncrieff Cochran has applied this theory specifically to the role of parenting within families but its principles can be applied to other family dynamics too. It suggests that the broader social, structural, and relational aspects of a parent’s life can affect a child’s well-being, either through the parent’s actions or directly on the child (Cochran 1990; Cochran et al. 1990; Cochran and Bassard 1979). Just like social network theory suggests, Cochran observed that it’s through the connections and interactions within these networks that information and behavior models from society can influence parenting.

The people you connect with in your social networks are often influenced by factors like your cultural background, income, education level, and where you live. Christakis and Fowler (2009) refer to this as situational inequality. Another important factor is what motivates you to include certain people in your network—like shared interests or needs. Understanding these factors can help us figure out how to encourage people to join and participate in networks.

The interactions within social networks—whether they involve parents directly or happen indirectly—can affect how parents behave. For example, receiving support from others, whether it’s practical help or emotional support, can influence parenting. Different aspects, like buffering stress, providing role models, teaching skills, offering direct assistance, and creating opportunities for interaction, can all play a part in shaping how parents behave.

Cochran’s model provides a helpful framework for studying how parents’ social networks, both online and offline, impact their parenting outcomes. This model encourages researchers to focus on both the process and structure of social relationships, recognizing their significance in understanding family dynamics. By adopting a network perspective, family researchers can explore additional aspects of parenting outcomes that arise from social network dynamics and can influence the child, such as parental growth and the parent-child relationship.

The internet serves as a powerful tool for information, communication, self-expression, and collaboration, potentially influencing the personal development of parents—for example, by providing validation of identity. Studying how online interactions affect parents can also reveal how these interactions might lead to benefits in offline settings, either directly for parents or indirectly for their children.

Couple and family technology framework

Hertlein (2012) presents a comprehensive model that examines how technology influences the dynamics of couples and families, including how they establish rules, roles, and boundaries, and interact with each other and the world around them (Hertlein 2018; Hertlein and Blumer 2013). This model combines insights from various theories, including family ecology, structural-functionalism, and interaction-constructionist theory.

The framework highlights unique aspects of digital communication, which Hertlein refers to as “vulnerabilities,” that differentiate it from face-to-face interaction. These vulnerabilities include characteristics such as:

- Anonymity: presence online can be masked.

- Accessibility: easier, 24/7 access to the individual.

- Affordability: the lower cost for means of interaction and entertainment.

- Approximation: social presence, or the feel and representation of face-to-face interaction through text and sensory elements.

- Acceptability: of using technology as the format for relationship communication.

- Accommodation: enabling the individual to behave like their real vs. their ought self.

- Ambiguity: problematic behavior resulting from time spent online.

These aspects can affect how communication is perceived, how relationships are formed and maintained, and individuals’ behavior within relationships.For example, children teaching parents how to use new technology like smartphones can lead to shifts in family roles. Couples may renegotiate what information they share about their relationship on social media, impacting relationship rules. A parent’s distraction by work messages while helping with schoolwork at home can blur family boundaries. Additionally, technology can facilitate changes in family processes, such as initiating relationships through dating apps or maintaining intimacy through videoconferencing during times of separation.

Technology use by couples

Given that the majority of households in the United States now have internet access and own smartphones, texting has become a primary way for couples to communicate (U.S. Census Bureau 2021). This trend is especially prevalent in households with younger leaders, in urban areas, and across all income levels. Couples find texting efficient, easy, and convenient (Nylander et al. 2012). Through calls and texts, couples express affection, deepen intimacy, solve problems, and gather information. Factors such as the length of the relationship, how close the couple is, and their familiarity with using cell phones predict how positively and frequently they use these communication methods.

Social media also plays a role in how some couples communicate about their relationship and learn more about potential partners (Vogels and Anderson 2020). Other technologies like videoconferencing, virtual reality, and augmented reality offer even more immersive ways for couples to connect. For instance, during the COVID-19 pandemic, there was a story about an elderly couple using FaceTime to stay in touch, even though one of them lived in assisted living. Some couples also use more sensory-mediated communication methods, such as cybersex, which involves activities like viewing pornography, sexting, and engaging in web-cam sex.

In a study involving college students, Hertein and Ancheta (2014) examined how technology is used in relationship initiation, management, and enhancement. They found that technology helps couples seek information, manage conflicts, reduce anxiety, and demonstrate commitment. Furthermore, technology can enhance relationships by adding excitement to sexual interactions and maintaining connection during periods of separation.

If a researcher asked you whether technology has affected your relationship, how would you respond? Would you want the researcher to clarify what they mean by “impact”? According to research conducted by Pew in 2014 (Lenhart and Duggan), couples generally viewed “impact” as something significant. Only 10% of couples who had been together for 10 years or more reported any impact from technology use, and in most cases, this impact was positive, leading to increased feelings of connectedness. However, younger age groups showed higher rates of impact, with 21% of individuals aged 18–29 reporting a major impact from technology.

A more recent study by Pew (Vogels and Anderson 2020) also found that couples didn’t feel significantly affected by seeing others post about their relationships on social media. Although 81% reported seeing these posts, the majority (81% of this group) said it didn’t affect their own relationships, and another 9% even felt better about their own relationships after seeing these posts.

Of course, there are drawbacks to using technology in relationships. Misunderstandings and differences in technology use are common. Sometimes, one partner may use devices or applications without including the other, leading to feelings of imbalance. Activities like video gaming, viewing pornography, or phubbing—ignoring a partner by focusing on a phone—can also lead to conflict. Additionally, technology may be used to assert power imbalances, such as by choosing to have difficult conversations or even breaking up online, or in extreme cases, through stalking, harassment, or withholding a partner’s access to technology, as seen in cases of intimate partner violence.

Although Information and Communications Technology (ICT) can improve how efficiently couples communicate and feel connected to each other, it’s evident that it can also lead to conflicts between them. Imagine a scenario where a couple faces a conflict. How might technology play a role in causing that conflict, and how does it affect the couple’s relationship? Instances such as checking a partner’s phone, keeping tabs on ex-partners through social media, or feeling insecure or jealous about the partner’s social media activity are more commonly reported by younger adults and those in unmarried relationships. Hertlein and Ancheta (2014) identified common themes related to technology interference in couples’ relationships, which will guide our discussion in this section. These themes are supported by the findings of other researchers who have explored how married couples use technology, such as Vaterlaus and Tulane’s study in 2019.

Messaging through text or sexting may appear impersonal to some individuals, leading to a sense of detachment from the communication process. A phenomenon known as phubbing in couples (also labeled PPhubbing, or Partner Phubbing), has garnered significant attention as a form of technoference (McDaniel and Coyne 2016). Research indicates that even among married and committed couples, more than half report that their partner gets distracted by their phone, with a similar number expressing discomfort with the amount of time spent on phones. Phubbing has been linked to various negative effects on couples, including decreased intimacy, reduced relationship and sexual satisfaction, a diminished sense of quality time, and negative impacts on mental health (Wang et al. 2017).

A study conducted with married couples in China (Chen et al. 2022) investigated the transmissive effects of phubbing, where one partner ignores the other after experiencing being ignored themselves. This behavior tends to spread within couples due to their interdependence and shared time. Interestingly, the study found that men were more likely to engage in phubbing when their wives did, but the reverse was not true, potentially due to gender role socialization. Additionally, the study highlighted the link between phubbing and relationship satisfaction, suggesting that lower satisfaction could contribute to increased phubbing.

Research in the U.S. indicates that women are more bothered by being ignored than men, particularly across various media platforms such as phones, social media, and video games. A study of long-term German couples revealed that phubbing behavior was more common among younger couples and was significantly associated with attachment anxiety. This suggests that couples with a more insecure attachment orientation may perceive phubbing as more detrimental to their relationship quality (Bröning and Wartberg 2022).

Couples may inadvertently avoid addressing issues by focusing on their phones or choose to discuss challenging topics through asynchronous text rather than face-to-face conversations. However, even the mere presence of a phone during shared time together can create a sense of distraction and interfere with feelings of intimacy (Turkle 2015).

Couples often find it easy for their partners to hide texts or sexts to others, as well as conceal online activities, including social media interactions like following an “ex.” This behavior can spark concerns about infidelity, also known as “digital jealousy” (Eichenberg et al., 2017). However, it’s important to note that defining infidelity involving the internet can be tricky, as described by Vossler (2016). Some common factors include efforts to maintain privacy, utilizing internet features for access and anonymity, and sudden discovery. Vossler’s review suggests that the impact on couples of cyber-infidelity resembles that of offline infidelity, leading to partner distrust, relationship conflicts, and potential breakup.

Especially among younger couples, social media is often used to gather information about their partner’s activities. Given that social media is a common platform for checking up on ex-partners, being aware of this behavior can lead existing partners to feel jealous or suspicious. However, it’s essential to recognize that looking at a partner’s phone or social media account without permission can breach boundaries and significantly damage trust. Regardless of age, commitment status, or other demographics, nearly three-quarters of couples (71%) agree that it’s not appropriate for a partner to snoop through their partner’s phone without their knowledge. Nevertheless, a significant portion (34%) of couples admit to doing so (Vogels and Anderson 2020).

The last challenge area for couples involves lack of clarity. As we’ve discussed, individuals vary widely in their access to, attitudes toward, comfort with, and skill in using technology. For instance, one partner may spend more time on their phone and frequently use social media, while the other may actively avoid social media altogether. Differences in texting habits, in particular, can lead to misunderstandings. For example, when a message isn’t promptly returned or is replied to late or with vague wording, a partner may question the sender’s intentions or misinterpret the message (Vaterlaus and Tulane 2019). Ambiguity in text messages and the use of emojis are common issues that can contribute to misunderstandings (Miller et al. 2017). When couples engage in significant discussions or conflicts via text (e.g., arguments, apologies), one or both partners may feel uncomfortable (Novak et al. 2016).

Most couples don’t openly discuss social media use as a potential relationship concern, even though individual partners may have unspoken rules that need to be addressed. Digital jealousy doesn’t seem to be tied to a specific platform and depends on how each couple defines cheating (Eichenberg et al. 2017). Through interviews with committed couples regarding their technology use integrated into daily life, researchers developed a process model outlining how boundaries and rules are negotiated (Pickens and Whiting 2020; Cravens and Whiting 2015). The definition of “committed” was determined by the couples themselves; researchers didn’t impose any specific criteria regarding duration or status. Understanding this process can help professionals offer guidance to couples dealing with conflicts.

The suggested steps are as follows:

- Identify the online issue, including any past problems or inappropriate behaviors.

- Evaluate the online issue, considering implicit and explicit rules, as well as the level of agreement on these rules.

- Discuss the online issue openly, providing evidence, justifying behaviors, or explaining perspectives.

- Work towards resolving the issue through monitoring and effective communication, or explore potential consequences that could lead to ending the relationship.

Couples might consider asking each other:

- Are there any websites you think I shouldn’t visit?

- Are there specific people or groups on social media that you’re uncomfortable with me interacting with?

- Do you have any preferences regarding what information should or shouldn’t be shared online about us or our relationship?

- How do you feel about pornography in the context of our relationship?

Couples’ therapist Veronica Marin (2017) offers the following advice for relationships:

- Prioritize spending at least 20 minutes a day of screen-free time together to make your partner feel valued.

- Discuss before posting anything about your relationship online.

- Establish expectations for texting habits.

- Interact online as you would in real life.

- Avoid snooping on your partner’s behavior; trust them unless there’s a clear reason for concern.

- Address any discomfort or issues promptly and rationally with your partner.

Family technology use

Researchers studying family dynamics and technology usage argue that the devices and apps families use can influence how family members interpret their interactions and shape their shared experiences. This, in turn, can reinforce family norms, values, and the sense of being connected. When used thoughtfully — and with an understanding of potential conflicts that may arise due to differences in comfort, skill, and perception of technology — media can play a positive role in strengthening family bonds.

Early research conducted by Padilla-Walker and colleagues (2012) explored the types of technologies used by families, specifically focusing on parents and their adolescent children, and how these technologies were linked to feelings of connectedness within the family. Connectedness, in this context, refers to the warm, loving, and positive relationships between parents and children or other family members. To measure connectedness, the researchers used items from the warmth/support subscale of the Parenting Styles and Dimensions Questionnaire-Short Version (Robinson et al. 2001). Participants rated statements such as “I have warm and loving times together with my child/parent” on a 5-point scale. The study found that cell phones, video games, and co-viewing media were significantly associated with greater family connectedness. However, email and social networking did not show a strong relationship with this outcome. Additionally, the researchers observed differences based on family characteristics, noting that parents with higher levels of education reported experiencing more connectedness related to their use of technology.

The authors suggested that watching media together as a family indicates shared interests and promotes open communication. When parents and children agree on what to watch, it can lead to a better understanding of each other’s perspectives, fostering discussions during or after the program. These findings are consistent with Nathanson’s (2002) research, which highlighted the role of co-viewing media in parents’ ability to guide content and children’s media exposure. Although a smaller number of teens reported playing video games with their parents, this co-playing was linked to stronger family connections. As discussed earlier, when children and parents engage together with media and technology, such interactions have the potential to bridge the digital gap and enhance family closeness.

Regarding email and social media, Padilla-Walker and colleagues (2012) found that these forms of communication were not associated with increased family connectedness. Email, being asynchronous, may feel less personal and more transactional, mainly used for sharing news and information. In our own research with over 1,500 families (Rudi et al. 2014), we found that the type of technology used varied among family members. Email and social networking were more popular among extended family members, while texting, seen as a more intimate form of communication, was primarily used between parents and children and between co-parents. Since then, email usage and perceptions have remained relatively unchanged among family members.

In contrast, social media has seen significant growth in terms of usage and applications. While early research by Padilla-Walker et al. (2012) reported limited parent-teen interaction on social media due to restrictions in personal expression and the perception that it was mainly for interactions between friends, recent studies suggest that social media can indeed strengthen family connectedness. A review by Tariq and colleagues (2022) identified several studies on social media use and family relationships, with most focusing on parents and adolescents. However, the authors note a lack of research on whole family dynamics and motivations behind family members joining social media platforms. Additionally, there’s a limited exploration of various social media applications beyond Facebook. For instance, adults’ use of platforms like Instagram or TikTok may depend on whether their child uses it or if they know other users on the platform (Nouwens et al. 2017).

Earlier research conducted by Stern and Messer (2009) explored how individuals stay connected with their relatives. They found that email and cellphones were commonly used to communicate with relatives who were farther away, while face-to-face visits were preferred for local relatives. Interestingly, the frequency of contact did not necessarily reflect the level of closeness between individuals. Instead, people tended to choose communication methods based on the level of closeness they desired with their relatives. In simpler terms, individuals tend to use the available technologies in ways that they believe are most effective for maintaining their relationships. As we learn more about the capabilities of different technologies and understand the variations in individual preferences, skills, and access, we realize that the use of technology for family communication is often tailored to complement emotional closeness and geographical proximity.

Since 2012, and particularly with the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, new technology has emerged as a significant tool for family communication: videoconferencing. Applications such as FaceTime, Skype, and Zoom have enabled real-time communication that goes beyond just voice or text, providing a more immersive experience. As noted by Lebow (2020), ongoing social science research will gradually uncover both the benefits and drawbacks of relying on videoconferencing for family communication during the COVID-19 pandemic. Families have faced considerable challenges, including loss, stress, and efforts to uphold family rituals and celebrations amidst the pandemic. Additionally, other factors influencing family dynamics during this time include addressing disparities in technology access and proficiency, as well as the broader impacts of supporting family members dealing with mental or behavioral health issues, such as facilitating access to support groups like AA meetings.

When it comes to technology use within families, research emphasizes the importance of clear communication about how devices are used. While we’ve explored how technology can enhance family communication and unity, focusing on communication also helps families establish shared rules about managing technology and device usage for the benefit of the whole family. However, establishing these rules may not be straightforward for everyone. As discussed previously, parents who feel more informed about the effects of technology are more likely to establish guidelines or engage in authoritative discussions to determine safe and reasonable usage. Conversely, parents who lack confidence in their knowledge about technology may either enforce strict rules without discussion or take a more hands-off approach regarding their children’s device use.

Children’s own attitudes towards and compliance with family rules regarding screen time and device usage will vary depending on their age and influences from their broader social environment. As indicated by Lanigan’s socio-technological framework, family technology rules are shaped by the attitudes, preferences, and behaviors of each family member. Therefore, discussions about family rules reflect the perspectives of all family members, with the goal of reaching shared understandings that meet the needs of everyone involved.

What are some strategies for achieving this, especially concerning screen time among family members? Let’s consider the example of phones during dinner time. For many families, dinner is a time when everyone gathers together. It’s a time for sharing food, catching up on the day’s events, and perhaps engaging in important cultural or religious traditions. Therefore, it’s concerning that phones have become a common distraction during mealtime, leaving family members feeling “alone, together,” as described by Turkle (2015).

In 2016, Commonsense Media conducted a study to explore the impact of devices at the dinner table. The study surveyed 869 individuals from families with at least one child between the ages of 2 and 17. Of those surveyed, 807 reported having devices, 770 reported eating dinner together in the past week, and 362 reported using technology during dinner. Interestingly, only about half of the families who ate dinner together also used technology during that time, suggesting that many families consciously choose to keep phones away during meals. Although dinner was considered important by the majority of families with devices, it wasn’t necessarily a time for discussing the day’s events for most families. Only 19% reported using mealtime for this purpose, with activities like driving the kids in the car being more common. While about half of the families using devices during dinner felt that it made them feel disconnected, 25% believed that phones actually brought the family closer together, likely through sharing information and photos. This study highlights the complexities of an issue that can present challenges for families without clear technology rules, while for others, the solution may be as simple as keeping phones away during mealtime.

There are various tools and resources designed to assist families in managing screen time and promoting safe technology use while also facilitating mutual agreement on technology usage. One such resource is the Family Media Plan provided by the American Academy of Pediatrics (2024). This tool encourages parents and children to collaborate in creating a personalized plan based on the child’s age. Together, they can select items from a comprehensive checklist to monitor the child’s daily technology use. What are the benefits for families in creating their own plan using such a checklist? One activity prompts you to devise a media plan for three children of different ages, allowing you to compare their proposed activities and how they align with their developmental stages. It also encourages reflection on the family’s ability to effectively monitor these actions. However, a critique of the Family Media Plan is its focus solely on children aged 18 and under, disregarding the challenges that parents themselves may face in managing their device usage, potentially causing distractions or unhealthy habits.

As we’ll explore in the following chapter, the ability to self-regulate and establish boundaries is becoming increasingly important for adults as they navigate the demands of work and family life in our tech-driven world, particularly in the aftermath of the COVID-19 pandemic. A digital media nonprofit’s family education platform suggests eight key elements that all families should consider:

- Total screen time

- Screen-free periods during the day

- Screen-free family gatherings, such as dinner time

- Avoiding phone use while driving

- Limiting screens before bedtime

- Addressing habits, like silencing phones to reduce the urge to check for messages

- Creating a family agreement or pledge regarding technology use

- Identifying activities for the family to enjoy together without screens.

While technology can sometimes cause distractions and conflicts within families, research shows that it also plays a significant role in promoting communication and strengthening family bonds. Nowadays, there is an abundance of applications and devices that facilitate collaboration, creativity, and communication among family members. During the COVID-19 pandemic, many families relied heavily on technology tools, particularly videoconferencing, as the primary means of staying connected with relatives, including those living far away due to factors like immigration, travel, or deployment. Additionally, video games can provide an enjoyable way for family members to bond, solve problems, and enhance cognitive skills, while also allowing parents to monitor their children’s media consumption.

However, as families face increasing busyness and stress, and children become adept at using technology from a young age, parents may struggle to use technology in ways that foster meaningful connections and maintain family harmony. Additionally, disparities in access, time, and financial resources can create inequalities both within and among families. Given these challenges and other demands of daily life, families must adapt and find ways to incorporate technology into their lives while ensuring that it enhances, rather than detracts from, family connectedness and unity.

ANALYZING FAMILY STRUCTURES

Children of the Force

The Children of the Force podcast, a product of Al Nowatski and his children, Liam and Anna (now teenagers), started in 2016, arose from their shared interest in Star Wars. Episodes can be found at their website: childrenoftheforce.com. Select at least one of the episodes to listen to. You can also watch this interview with the family from 2022: https://youtu.be/8z2iknECiCM?si=cKEjKeKFzDEdaD3T.

Write a response to the questions below, incorporating insights from the podcast. Your response should be well-organized and supported with specific examples or quotes from the episode.

- What does the activity mean to the family sense of closeness or cohesion? How does the activity serve as a platform for family communication, and as a demonstration of family flexibility?

- How is Al asserting his role in the family? How are his children asserting their roles as children? How does the technology experience affect the execution of those roles, rules, and structure? How does it affect the processes of relationship maintenance and strengthening?

- Consider the contribution of creating this podcast to each child’s development over time. In what ways might it influence the sense of identity? Self-concept? Social awareness?

- How might Al operate as a “learning hero” as one or both of the children build on the podcast experience to engage with their interests?

Adapted from Walker, Susan K. 2022. Critical Perspectives on Technology and the Family. University of Minnesota Libraries Publishing. Retrieved April 1, 2024 (https://open.lib.umn.edu/technologyfamily/).