6.5 Divorce

Divorce is the legal ending of a marriage. Whether or not couples choose to pursue divorce can be influenced by various factors within society. Divorce, once a taboo topic, has become more common and accepted in modern U.S. society. In 1960, divorce rates were relatively low, affecting only 9.1 out of every 1,000 married individuals. However, by 1975, this number more than doubled to 20.3 and peaked in 1980 at 22.6. Over the past twenty-five years, divorce rates have steadily declined and are now similar to those in 1970 (Wang 2020). The significant increase in divorce rates after the 1960s has been linked to the liberalization of divorce laws and the changing societal dynamics with more women entering the workforce (Michael 1978). Figure 6.3 describes the decrease in divorce rates can be attributed to three likely factors: first, an increase in the average age at which people marry; second, higher levels of education among those entering marriage, both of which contribute to greater marital stability. Third, the overall decline in marriage rates also leads to a decrease in divorce rates. In 2019, there were 16.3 new marriages for every 1,000 women aged 15 and over in the United States, down from 17.6 in 2009 (Anderson 2020).

Divorce rates vary among different segments of the U.S. population. According to the American Community Survey (ACS), the Northeast and Midwest regions have lower divorce rates compared to the South, which generally has the highest divorce rates. This disparity can be attributed to higher marriage rates and younger ages at marriage in the South, while in the Northeast, lower marriage rates and delayed first marriages contribute to lower divorce rates (Reynolds 2020). However, there are exceptions to these general trends; for example, the District of Columbia has a high marriage rate but one of the lowest divorce rates (Anderson 2020).

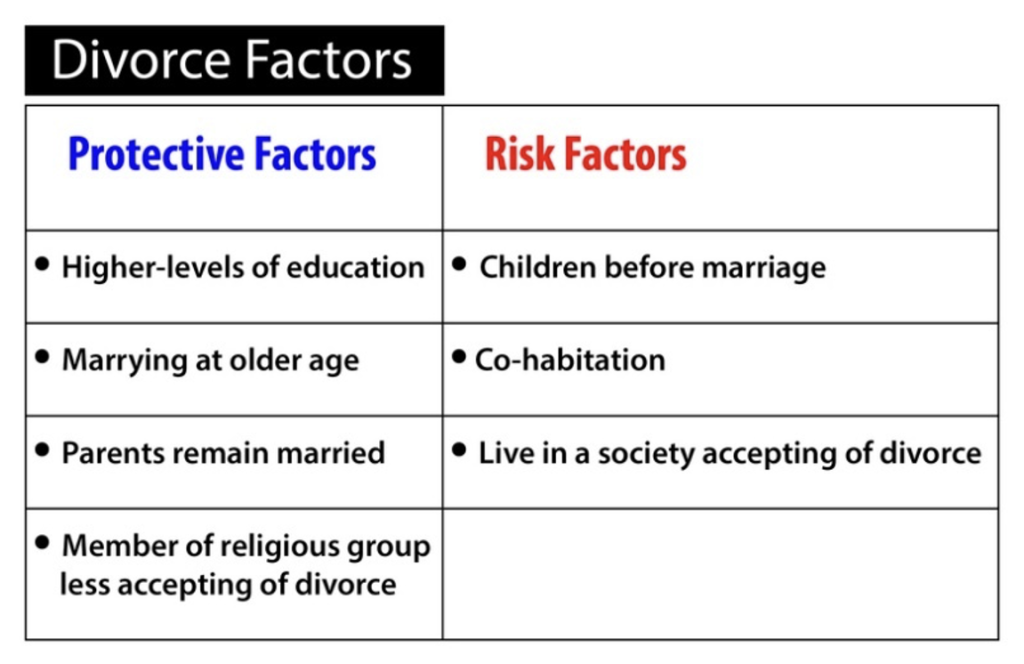

Table 6.3. Divorce Factors

Source: Payne, Whitney. 2020. Human Behavior and the Social Environment II. Fayetteville, AR: University of Arkansas Libraries.

Various factors contribute to divorce. Financial stress is a significant predictor of marital problems, with couples lacking a strong financial foundation being more likely to divorce. The addition of children to a marriage can exacerbate financial and emotional strain, particularly in the early years of parenthood. Research indicates that marriages face increased stress after the birth of the first child, especially for couples with multiples (Popenoe and Whitehead 2007). Additionally, declining marital satisfaction over time and diverging life goals between partners can also lead to divorce (Popenoe and Whitehead 2004).

Divorce tends to follow a cyclical pattern, with children of divorced parents being more likely to divorce themselves. Moreover, the likelihood of divorce increases significantly for children of parents who divorced and remarried. This may be attributed to a mindset learned from parental experiences, suggesting that a broken marriage can be replaced rather than repaired (Wolfinger 2005). Additionally, marriages where both partners have been previously divorced are significantly more likely to end in divorce (Wolfinger 2005).

Approximately 15 percent of married couples involve one partner in their second marriage while the other is in their first marriage. Additionally, about 9 percent of married couples are both in their second marriage (U.S. Census Bureau 2006). The vast majority of remarriages, accounting for 91 percent, occur after divorce, whereas only 9 percent occur following the death of a spouse (Kreider 2006). Most men and women remarry within five years of a divorce, with the median time being three years for men and 4.4 years for women. This trend has remained relatively consistent since the 1950s. The majority of individuals who remarry fall between the ages of twenty-five and forty-four (Kreider 2006). Additionally, statistics indicate that White individuals are more likely to remarry compared to Black individuals.

Remarrying, whether it’s the second, third, or fourth time, often differs significantly from the first marriage experience. The process of remarriage typically lacks many of the traditional courtship rituals associated with first marriages. In a second marriage, individuals are less likely to encounter issues such as parental approval, premarital sex, or discussions about desired family size (Elliot 2010). A survey examining households formed through remarriage found that only 8 percent comprised solely of the remarried couple’s biological children. Among households with children, 24 percent included only the woman’s biological children, 3 percent had only the man’s biological children, and 9 percent had a mix of both spouses’ children (U.S. Census Bureau 2006).

Divorce and remarriage can be challenging experiences for both partners and children. While divorce is often seen as a solution to parental conflict, long-term studies suggest otherwise. Research indicates that although marital conflict isn’t ideal for childrearing, divorce itself can be harmful. Children often feel confused and frightened by the instability divorce brings to their family life. They may even blame themselves for the divorce and try to reconcile their parents, often at the expense of their own well-being (Amato 2000). Surprisingly, only in highly conflict-ridden homes do children benefit from divorce by experiencing reduced conflict afterward. However, most divorces occur in homes with lower levels of conflict, and children from such households are more negatively affected by the stress of divorce than the unhappiness within the marriage (Amato 2000). Furthermore, studies suggest that stress levels for children don’t necessarily improve when they gain a stepfamily through remarriage. Despite potential economic stability, stepfamilies often face interpersonal conflicts (McLanahan and Sandefur 1994).

The impact of divorce on children may vary depending on their age. School-aged children, for example, may find divorce particularly challenging as they can comprehend the separation but may struggle to grasp its reasons. Older teenagers may understand the conflict that led to divorce but still experience fear, loneliness, guilt, and pressure to take sides. Infants and preschool-age children, on the other hand, may suffer from disruptions to their routines that marriage once provided (Temke 2006).

The proximity to parents also affects a child’s well-being after divorce. Boys who have joint arrangements with their fathers tend to show less aggression than those raised solely by their mothers, while girls who live or have joint arrangements with their mothers tend to demonstrate more responsibility and maturity than those raised solely by their fathers. However, the majority of children of divorced parents, nearly three-fourths, live in households headed by their mothers, leaving many boys without a father figure present (U.S. Census Bureau 2011). Nonetheless, research suggests that a strong parent-child relationship can significantly enhance a child’s adjustment to divorce (Temke 2006).

Despite experiencing divorce, children haven’t been discouraged regarding their views on marriage and family. Blended families, formed through remarriage, face additional stressors from combining children from previous and current relationships, as well as differences in disciplinary approaches. Surveys conducted by researchers from the University of Michigan have found that a large majority of high school seniors still place great importance on having a strong marriage and family life, with many believing in the likelihood of lifelong marriage (Popenoe and Whitehead 2007). These attitudes toward marriage and family have continued to increase over the past twenty-five years.

ANALYZING FAMILY STRUCTURES

Happiness & Divorce

Research and review findings regarding the concept of divorce and happiness.

- Share your source and summarize your findings in a few sentences.

- Does divorce increase happiness? Discuss why or why not.

- Discuss how a conflict theorist would explain the function of divorce in society.

“Happiness & Divorce” by Katie Conklin, Lemoore College is licensed under CC BY 4.0

Odds of divorce

Firstly, the likelihood of divorce isn’t high among today’s married couples since they typically stay together. Secondly, it’s crucial to understand that while the national divorce rate may seem daunting, your personal risk of divorce depends largely on your own actions within your marriage. You and your partner have significant control over your marriage’s quality and outcome. How you nurture it, shield it from various stresses like health or financial issues, and actively maintain it play a vital role.

Researchers in the field of family science describe marital entropy as the idea that without ongoing care and improvements, marriages can deteriorate over time. Rather than being overly influenced by reports of national divorce rates, investing in activities like a weekend getaway to reignite romance and reinforce commitment is a more effective strategy against marital decay. Taking proactive steps to enhance your marital satisfaction has a greater impact than most other factors contributing to divorce.

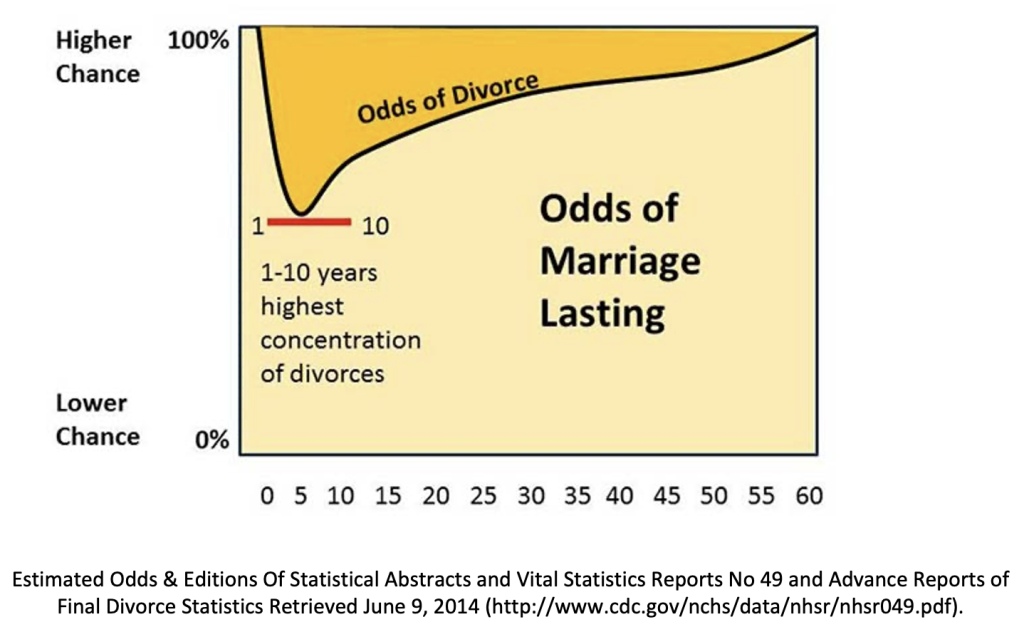

It’s also worth noting that the longer a couple stays married, the less likely they are to divorce. The initial years of marriage involve significant adjustments, particularly in establishing a unified relationship where both partners negotiate various aspects like finances, intimacy, social interactions, emotions, intellect, physicality, and spirituality. Figure 6.5 describes by around years 7-10, many couples have settled into their roles and agreements. Despite the possibility of divorce at any stage, the accumulation of shared experiences such as having children, building wealth, gaining social recognition, and navigating life’s challenges together often makes divorce less appealing, even when certain aspects of the marriage aren’t ideal (refer to Levinger’s Model in Table 6.4).

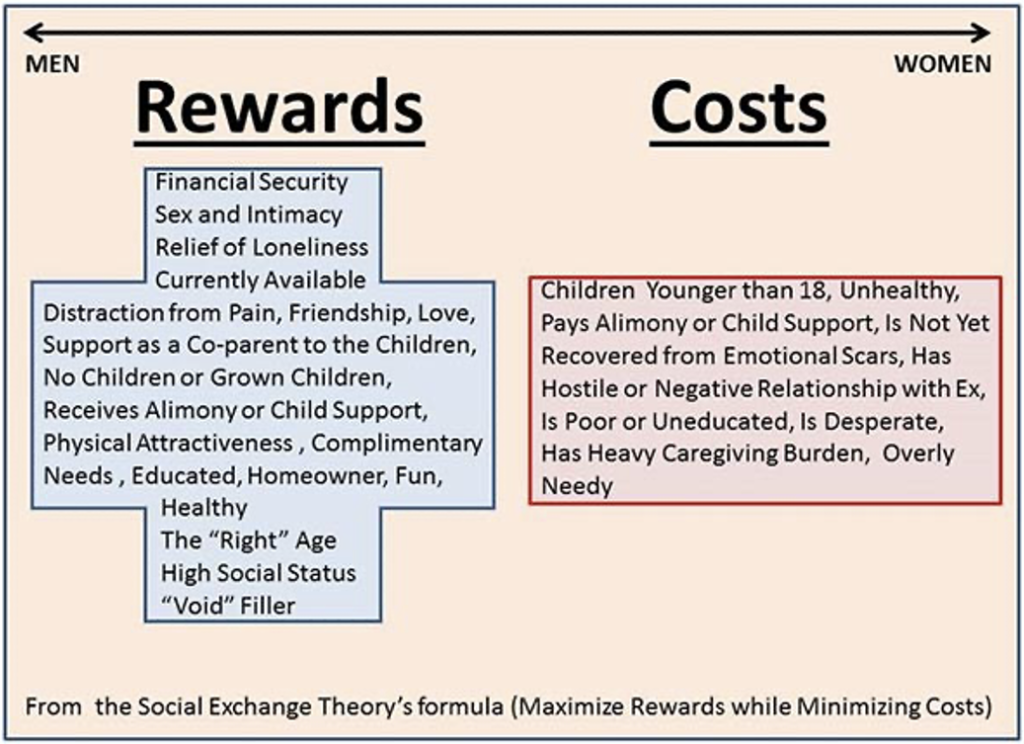

When using social exchange theory to understand why couples either stay married or get divorced, we delve into how spouses weigh the costs and benefits, rewards and punishments, or pros and cons in their decisions. Social exchange theory suggests that society is built on continuous interactions among individuals who aim to maximize rewards while minimizing costs. Although similar to conflict theory in some assumptions, Social exchange theory emphasizes the interactive nature of these assumptions. Essentially, it views humans as rational beings capable of making informed choices when they understand the pros and cons.

Figure 6.5. Estimated Odds of Marriage Lasting

Source: Hammond, Ron, Paul Cheney, Raewyn Pearsey. 2021. Sociology of the Family. Ron J. Hammond & Paul W. Cheney. Retrieved April 2, 2024 (https://freesociologybooks.com/Sociology_Of_The_Family/09_Marriage_and_Other_Long-Term_Relationships.php).

This theory employs a simple formula to gauge decision-making processes:

(REWARDS – COSTS) = OUTCOMES

or

(What I gain – What I sacrifice) = My decision

In 1979, Levinger and Moles discussed the rational choices made by spouses contemplating divorce or staying married in a chapter of a scholarly anthology. This discussion has come to be known as “Levinger’s Model.” Levinger’s Model can be represented in the following formula:

(Attractions – Barriers) +/- Alternative Attractions = My decision to stay married or divorce

Refer to Table 6.4 below for an illustration of how Levinger’s Model elucidates the choices people might make and their perceived rewards and costs.

Levinger’s Attractions represent the positive aspects or rewards of being married. These are the benefits or magnets that marriage brings, such as gaining social status, building wealth together, raising children together, enjoying sexual intimacy, and receiving emotional support and stress relief from one’s spouse. On the other hand, Levinger’s Barriers represent the negative aspects or consequences that may arise if a married individual decides to get divorced. These could include losing all the attractions of marriage, experiencing a decline in social status, dividing assets, managing co-parenting from a distance, facing changes in sexual intimacy, and losing the emotional support and stress relief provided by marriage, even if the marriage is unhappy.

Levinger’s Alternative Attractions, on the other hand, are the tempting or appealing factors that a married person might find attractive if they were to pursue a divorce. These could include the sense of freedom and independence that comes with being single again, financial independence from the ex-spouse and sometimes reduced financial responsibilities towards children (a perspective often observed among men who share custody but may have lower financial obligations), experiencing relief from parenting duties when the children are with the other parent, freedom from unwanted sexual demands, the possibility of finding new romantic partners, and escaping from stressful situations within the marriage.

Let’s focus on the last two rows of Table 6.4. They demonstrate how a simple formula can help us understand whether a couple is likely to stay married or get divorced. In the Stay Married formula, both the Attractions and Barriers are high, while the lures are low. In Social Exchange terms, this means there are numerous rewards in the marriage along with significant obstacles that would make divorce challenging. Moreover, there are few tempting factors pulling a spouse away from the marriage.

Conversely, the divorce formula paints a different picture. Here, attractions are low, barriers are low, and lures are high. Essentially, there are minimal benefits from being married, few perceived obstacles to divorce, and strong attractions outside the marriage enticing a spouse to leave. It’s logical to expect satisfied couples to align with the stay married formula, while dissatisfied ones might lean towards the divorce formula. However, it’s essential to note that these formulas merely describe the state of the relationship and cannot predict the couple’s actions. Some couples with a divorce formula may remain married for years, while others with a stay married formula may become dissatisfied and start considering alternatives.

One key concept in social exchange theory that sheds light on couples’ decision-making processes is equity. Equity refers to a sense that interactions are fair to both individuals and others involved. For instance, why is it that in couples where both partners work full-time, men typically don’t contribute as much to housework and childcare as their wives? Research suggests that it often comes down to perceptions of fairness or equity. This could be because the wife views household chores as her responsibility, disagreements arise when she tries to involve her partner in these tasks, or she perceives him as incompetent. Consequently, even though the arrangement may be unequal, the couple may perceive it as fair (Pleck 1985).

Table 6.4. Levinger’s Model of Rational Choice in Divorce

| Attractions – Magnets = Rewards that stem from being married | Barriers () +/- Walls = Punishments or losses you’d face if you divorced. You’d have to climb over these walls if you divorced. | Alternative Attractions Lures Away From Your Marriage = Something attractive that you could obtain if you were unmarried. |

|---|---|---|

| Positive social status | Loss of positive status and gain of new negative-status stigma of being divorced | Liberated status with freedom to explore relationships with others |

| Wealth accumulation | Division of wealth (at least by half) | Opportunity to be disentangled from family costs |

| Co-parenting | Co-parenting with ex-spouse — never truly free from this role | Shared custody, alleviating some degree of burden of parenting |

| Sex | Much less availability and predictability of sexual partner | Possibility of new sexual partner |

| Health support and stress buffer | Loss of health support and additional stress from divorce process | Different types of stressors and relief from pre-divorce stresses |

| Stay married formula ↑ attractions | ↑ barriers | ↓ lures |

| Divorce formula ↓ attractions | ↓ barriers |

↑ lures |

Levinger, G. and O.C. Moles. 1979. Divorce and Separation: Context, Causes, and Consequences. Basic Books

Source: Hammond, Ron, Paul Cheney, Raewyn Pearsey. 2021. Sociology of the Family. Ron J. Hammond & Paul W. Cheney. Retrieved April 2, 2024 (https://freesociologybooks.com/Sociology_Of_The_Family/09_Marriage_and_Other_Long-Term_Relationships.php).

Predictors of divorce

Decades of research on divorce have identified several common factors that can increase or decrease a couple’s likelihood of divorcing. However, before delving into these factors, it’s important to acknowledge an uncomfortable truth: just as we all face the risk of dying as long as we’re alive, being married means we’re also susceptible to the risk of divorce. However, it’s crucial to note that the presence of divorce risks doesn’t necessarily determine the outcome of divorce.

Geography plays a significant role in divorce rates across the United States. Divorce rates tend to be lower in the Northeastern region and higher in the Western region. Nevada often stands out with the highest divorce rates among all states, although it’s frequently excluded from comparisons due to what’s known as the “Vegas marriage” or “Vegas divorce” effect.

Historically, divorce rates have consistently been higher in the Western United States and lower in the Northeastern region. This variation in divorce rates is influenced by geography and the cultural norms prevalent in each area. Changing the cultural norms of a state is a more challenging task compared to making personal adjustments within one’s own marriage.

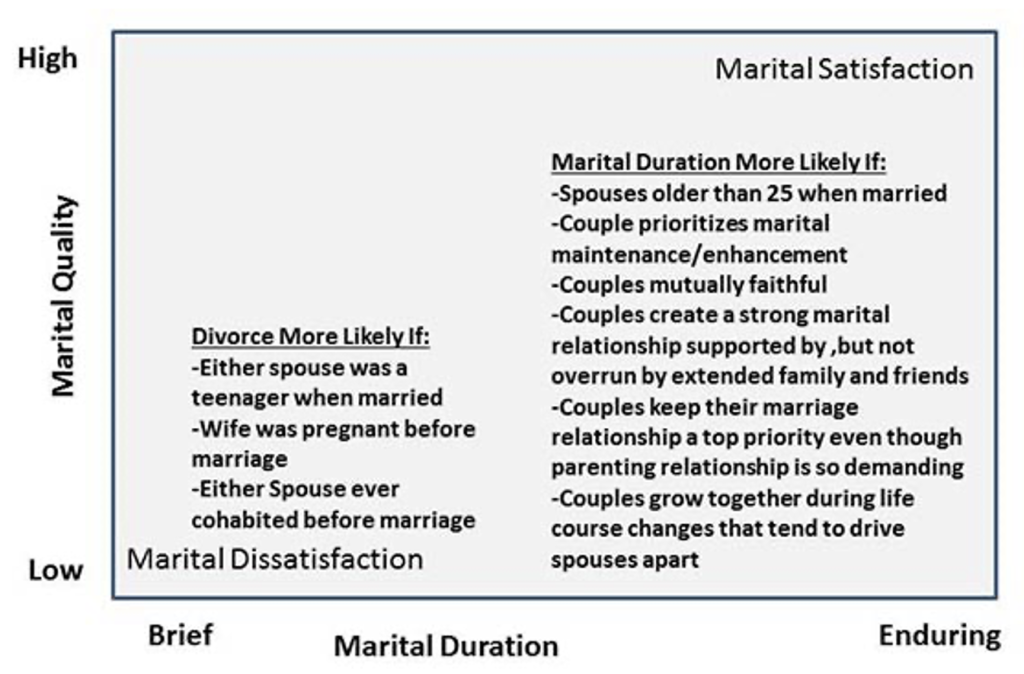

Figure 6.6 illustrates some of the choices individuals can make within their marital relationships to decrease their risk of divorce. A significant portion of the factors contributing to divorce largely fall within an individual’s control and choices. For instance, research suggests that delaying marriage until at least one’s 20th birthday significantly reduces the risk of divorce. Interestingly, the optimal ages for marriage fall between 25 and 29, coinciding with the U.S. median age at marriage for both men and women. Conversely, getting married at a younger age, such as 15 to 19, poses a considerably higher risk of divorce. This is because individuals in this age group may face economic, social, and emotional disadvantages. Waiting until age 25 allows individuals to graduate college, prepare for employment, and develop emotional maturity, as supported by various scientific studies indicating that key social and intellectual capacities may not fully develop until around age 26. Additionally, marrying due to an unplanned pregnancy often increases the risk of divorce, even though many single mothers eventually marry the child’s father.

Figure 6.6. Factors Associated with Divorce and Marital Satisfaction

Source: Hammond, Ron, Paul Cheney, Raewyn Pearsey. 2021. Sociology of the Family. Ron J. Hammond & Paul W. Cheney. Retrieved April 2, 2024 (https://freesociologybooks.com/Sociology_Of_The_Family/09_Marriage_and_Other_Long-Term_Relationships.php).

Moreover, some individuals struggle to fully commit to marriage, maintaining a mindset of being available for a potentially “better” partner. This attitude reflects a cultural value that marriage is temporary, subject to change if a more desirable partner comes along. This notion is captured by Norval D. Glenn in his 1991 article, which highlights the cultural values influencing divorce risks.

Robert and Jeanette Lauer (2009), experts in family studies, conducted extensive research on long-lasting marriages and identified key factors contributing to marital endurance, such as viewing one’s spouse as a best friend and having mutual liking for one another.

In dealing with irreconcilable differences, negotiation and acceptance play crucial roles in maintaining a happy marriage. Additionally, maintaining a positive outlook on the marriage is vital, as marital satisfaction can fluctuate over the years, especially during the initial adjustment period of the first decade of marriage.

Family scientists also draw from physics the concept of entropy, which suggests that without proactive efforts to nurture the marriage, it may deteriorate over time. Hence, investing in preventive measures to maintain the marriage is essential.

Despite negative media portrayals of marriage, it remains a preferred lifestyle for the majority of U.S. adults. From a social exchange perspective, marriage is viewed as desirable and rewarding, with individuals seeking to maximize rewards while minimizing risks. Personal-level actions can be taken to mitigate the risk of divorce, as outlined in Table 6.5 below.

Table 6.5. Ten Actions Individuals Can Take to Minimize the Odds of Divorce

- Wait until at least your 20s to marry. Avoid marrying as a teenager.

- Don’t marry out of duty to a child. Avoid marrying just because she got pregnant. Pregnancy is not a mate-selection process we discussed in the pairing-off chapter.

- Become proactive by maintaining your marriage with preventative efforts designed to avoid breakdowns. Find books, seminars, and a therapist to help you both work out the tough issues.

- Never cohabit if you think you might marry.

- Once married, leave the marriage market — avoid keeping an eye open for a better spouse.

- Remain committed to your marriage. Most couples have irreconcilable differences and most learn to live comfortably together in spite of them.

- Keep a positive outlook. Avoid losing hope in your first 36 months — those who get past the three-year mark often see improvements in quality of marital relationship, and the first 36 months have the most intense adjustments in them.

- Take the media with a grain of salt. Avoid accepting evidence that your marriage is doomed — this means being careful not to let accurate or inaccurate statistics convince you that all is lost, especially before you even marry.

- Do your homework when selecting a mate. Take your time and realize that marrying in your late 20s is common now and carefully identify someone who is homogeneous to you, especially about wanting to be married.

- Focus on the positive benefits found to be associated with being married in society while learning to overlook some of the downsides.

Source: Hammond, Ron, Paul Cheney, Raewyn Pearsey. 2021. Sociology of the Family. Ron J. Hammond & Paul W. Cheney. Retrieved April 2, 2024 (https://freesociologybooks.com/Sociology_Of_The_Family/09_Marriage_and_Other_Long-Term_Relationships.php).

Over the years, numerous studies have consistently found that individuals with a history of cohabitation (having lived together before marriage) are more likely to divorce. Cohabitation has been extensively researched, particularly in comparing cohabiting couples with married ones. Studies by Lawrence Ganong and Marilyn Coleman (2017) have shed light on this topic. Their findings consistently reveal that cohabitation and marriage are fundamentally different. People who cohabit often develop relationship patterns that later hinder the longevity of their marriages. In simpler terms, those who cohabit before marriage are at a higher risk of divorce compared to those who never cohabited.

As mentioned earlier, cohabitation is now more prevalent in the United States than ever before. Cohabitating couples differ from married couples in several ways although there are some similarities in their lifestyles. Both groups form and sometimes end relationships. However, cohabiters face more than double the risk of relationship dissolution compared to married individuals as indicated by research conducted by Andrew J. Cherlin (2008).

Cherlin’s research also highlights the unique aspects of cohabiting versus married couples. In summary, cohabiters often feel financially unprepared for marriage, have lower expectations regarding relationship satisfaction, and anticipate shorter relationships compared to married individuals. The main focus of Cherlin’s work revolves around the impact of adult relationship stability on children.

Effects on children

Growing up with divorced parents doesn’t necessarily mean you’re worse off than children whose parents stayed married but created a harsh and unhealthy home environment. For many children and their parents, divorce can actually be a positive life change. Some children of divorce grow up to have very happy marriages themselves because they actively seek safe and compatible partners and are determined not to repeat the mistakes of their parents. However, having a parent who went through a divorce might increase the likelihood of divorce for many children.

Judith Wallerstein (2000) has been studying a clinical sample of children of divorce for nearly four decades. Her findings align with those of other researchers – children whose parents divorced are affected in various ways throughout their lives. Similarly, children raised in toxic home environments by parents who remained married also experience long-term impacts.

When a couple decides to divorce (or separates, for couples who were living together), it can bring significant changes to the stability of children’s lives on multiple levels. Many of these children have experienced divorce more than once. When their parents divorce, children often feel responsible and may believe that they should try to reconcile their parents, like in the movie Parent Trap. However, in reality, children typically don’t directly cause their parents to divorce – while they play a role, they are seldom the sole reason for it. Additionally, divorce itself brings about changes, which can be inherently stressful. Children may worry about abandonment, feel that their fundamental attachment to their parents has been disrupted, and struggle to reconcile their idealized view of family life with the reality of the situation. They become aware of tensions between their parents and may even become subjects of these tensions themselves.

Table 6.6. Core Guidelines for Divorcing Parents

- Respect each other, get along, and come to terms with the nuances of co-parenting (both parents and their new partners will be at the kindergarten play).

- Set up and maintain predictable routines, especially following mandates in the divorce settlement decree.

- Take mediation and adhere to mediation guidelines.

- Get professional help for children when needed.

- Ensure the constant safety and well-being of your children.

- Follow a mutually agreed upon divorce decree.

- Help children remember the good times that happened before the divorce.

- Expect children to act out in unexpected ways, and work with ex-spouse on being consistent and agreeing on how to discipline consistently. Encourage children to have a strong relationship with both parents.

- Get your own professional help, and guard against your children becoming caregivers to you.

- Take a co-parenting course to learn how to get along for the sake of the children.

Source: Hammond, Ron, Paul Cheney, Raewyn Pearsey. 2021. Sociology of the Family. Ron J. Hammond & Paul W. Cheney. Retrieved April 2, 2024 (https://freesociologybooks.com/Sociology_Of_The_Family/09_Marriage_and_Other_Long-Term_Relationships.php).

It’s crucial to prepare children for the impending divorce. Listen to their concerns and provide reassurance. Make it clear to them that they are not to blame for the divorce, and both parents still love them and will continue to be there for them. Assure them that they will be taken care of to the best of your abilities. Demonstrate that despite the challenges of divorce, you and the other parent can work together to navigate through it. Show them that you are committed to fostering a positive relationship with the absent parent, and encourage them not to take on the burdens associated with the dissolved marriage, such as acting as messengers or intermediaries between parents. Table 6.6 outlines some fundamental guidelines for parents going through a divorce.

Remarriage & Stepfamilies

Remarriage occurs when a man and woman legally marry each other after ending a previous marriage. Stepfamilies are created when children from a previous marriage or relationship become part of a new family through remarriage. Stepfamilies can be formed in several ways: when one or both spouses were previously married, when one or both spouses cohabited before marriage, or when one or both spouses were single parents and bring children from their previous relationship into the new family. Stepchildren can be of any age. In cases where a current spouse had a significant emotional or legal relationship before, it results in a bi-nuclear family, where the family structure revolves around two primary adult relationships formed by the original adults who are no longer together.

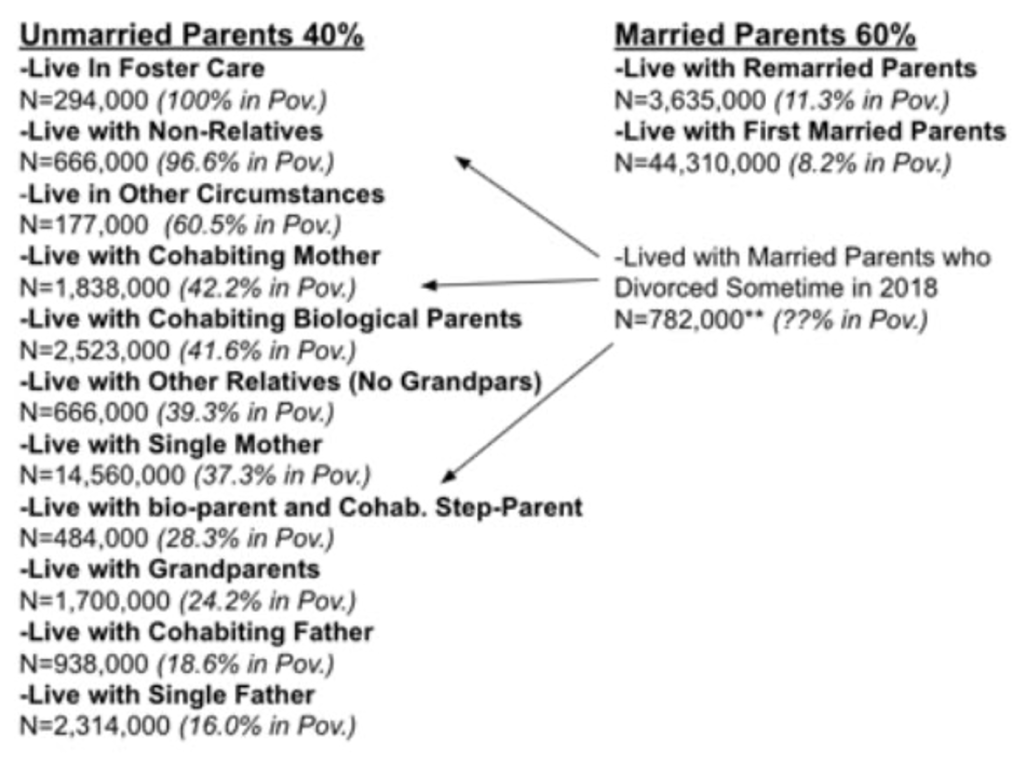

Figure 6.7 illustrates various family structures in the United States and their impact on children’s stability, particularly regarding poverty rates. In 2018, there were 29.5 million children living in unmarried homes (40%) and 44.2 million children living in married homes (60%). The figure also shows the percentage of children within each category living in poverty, with the highest poverty rates listed at the top of each list.

In married homes, the data reveals that children living with their original biological or adoptive parents who were still in their first marriage had the lowest poverty rate (8.2%), followed closely by children in homes with remarried parents (11.3%).

On the other hand, in unmarried homes, there is a clear gender trend, with the lowest poverty rates found in homes with single fathers (16.0%) and cohabiting fathers (18.6%). Poverty rates increase as you move up the list, with the highest levels of poverty observed in homes with children living in formal foster care (100%).

The reasons behind these higher poverty levels in unmarried parent homes are multifaceted, including factors such as cohabitation, divorce, single motherhood, substance abuse, crime involvement, and incarceration, which are more prevalent among the less educated poor compared to the more educated middle and upper class. This highlights how the instability experienced by children due to the “Marriage Go Round” actions of parents in the U.S. is exacerbated by poverty.

Researchers in sociology and related fields often discuss the concept of family instability, which refers to disruptions in children’s emotional and social bonds, relationships, living arrangements, and day-to-day lives resulting from changes in their parents’ significant relationships. Figure 6.7 illustrates this instability tends to be more prevalent among low-income families and less common in middle-class and upper-class families.

In 2013, Alan J. Hawkins, Ph.D., a leading figure in family studies, published a book titled “The Forever Initiative: A Feasible Public Policy Agenda to Help Couples Form and Sustain Healthy Marriages and Relationships.” Dr. Hawkins has dedicated over 25 years to studying the impact of mandated parenting classes on couples going through divorce. In some U.S. states, couples with children under 18 are required to take these courses when divorcing to learn how to co-parent effectively despite no longer being married. Dr. Hawkins assesses the effectiveness of these courses in helping families transition from one married household to two separate households while still sharing custody and care of their children. He also emphasizes the value of premarital education in promoting family stability and well-being.

Figure 6.7. Instability of U.S. Children (N=73,740,000)

American Community Survey. 2018. Table FAM1.B. Retrieved July 16, 2020 (https://www.childstats.gov/americaschildren/tables/fam1b.asp); Number of Divorices. 2000-2018. Retrieved July 16, 2020 (https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/dvs/national-marriage-divorce-rates-00-18.pdf)

Source: Hammond, Ron, Paul Cheney, Raewyn Pearsey. 2021. Sociology of the Family. Ron J. Hammond & Paul W. Cheney. Retrieved April 2, 2024 (https://freesociologybooks.com/Sociology_Of_The_Family/09_Marriage_and_Other_Long-Term_Relationships.php).

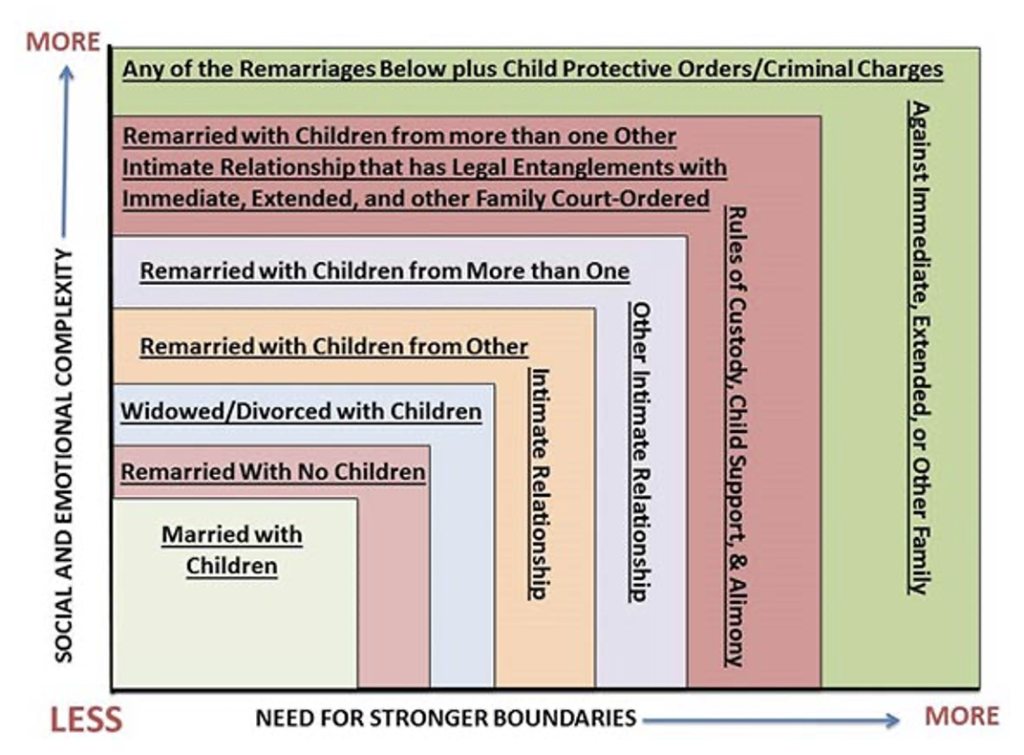

Given the crucial role of family function and structure in maintaining stability, numerous studies have explored how stepfamilies form and navigate their complexities. Stepfamilies are often regarded as one of the most intricate family systems due to their multiple social arrangements over time, such as multiple marriages, cohabitation, or common-law arrangements. This complexity increases the need for robust boundary maintenance within these families. Figure 6.8 presents a diagram outlining various types of relationships and the associated complexities and boundaries they entail. Compared to other relationship categories depicted, a married couple with children typically experiences lower levels of social and emotional complexity.

Establishing good boundaries is essential for healthy family dynamics. The saying “Good fences make great neighbors” underscores the importance and benefits of maintaining healthy boundaries within families. In a nuclear family, effective boundaries act like fences, safeguarding the immediate family and regulating interactions with others as deemed appropriate. Within a nuclear family, healthy boundaries encompass several aspects:

- Healthy sexual boundaries: Reserved for the spouse or partners only.

- Healthy parenting boundaries: Parents take on the responsibility of caring for, nurturing, and providing structure to their dependent children.

- Healthy financial boundaries: Parents teach their children the value of work and independence over time.

- Healthy emotional boundaries: Family members respect each other’s privacy and protect against intrusions from other family and friends.

- Healthy social boundaries: Friends and extended family members have their designated place, distinct from the intimacy shared within the immediate family.

- Healthy physical boundaries: Immediate family members have their own designated rooms, access to bathrooms, locks on doors and windows, and private space.

- Healthy safety boundaries: Older immediate family members protect the family from external threats and harm.

Maintaining these boundaries helps create a secure and harmonious family environment.

Couples who remarry without children, regardless of their previous marriage or cohabitation, typically experience less complexity. This is because there are no concerns about visitation disputes, child support, or holiday arrangements that often arise in remarriages with children. While there may still be issues regarding alimony, they are not as intertwined with co-parenting arrangements as in cases of joint custody or non-custodial conditions.

Figure 6.8. Stepfamilies & Other Family Subsystems

Source: Hammond, Ron, Paul Cheney, Raewyn Pearsey. 2021. Sociology of the Family. Ron J. Hammond & Paul W. Cheney. Retrieved April 2, 2024 (https://freesociologybooks.com/Sociology_Of_The_Family/09_Marriage_and_Other_Long-Term_Relationships.php).

For widowed or divorced individuals, boundary issues may become more pronounced, especially if they become reliant on others for financial or social/emotional support. Dependence can blur boundaries, particularly when single parents receive support from other adult family members or non-relatives. In contrast, intact couples who head the family unit and work together tend to maintain healthier boundaries. In many cases, adults who step in to assist children also provide support to single parents in various ways.

Remarried couples with children from previous relationships face additional complexity. The influence of the ex-spouse in co-parenting arrangements can encroach upon the boundaries of the remarried couple if not carefully managed. Scheduling in remarried families must be flexible to accommodate celebrations and events involving both the remarried couple and the ex-spouse’s family. This flexibility is necessary as situations may not always go as planned, requiring both parties to adapt.

Furthermore, remarried couples with children from multiple relationships encounter even greater complexity and boundary demands. Legal entanglements from previous relationships, including custody arrangements, visitation schedules, and alimony agreements, add layers of scrutiny and complexity. Compliance with court orders becomes essential, with meticulous record-keeping required to demonstrate efforts to adhere to legal obligations. However, perfection in meeting these obligations is unrealistic, and unexpected challenges may arise.

In cases involving criminal charges or child protective orders, the need for stronger boundaries becomes even more critical. Children must be safeguarded, and non-compliance with protective orders can result in legal consequences. Under such circumstances, supervised visitation may be ordered to ensure the safety of all parties involved. The involvement of the state in holding families accountable adds further intensity to these situations.

As many of you are aware, family relationships can become strained in various ways. This is especially challenging in remarried families where unresolved conflicts and boundary issues often persist. A significant model developed in the late 1970s sheds light on family dynamics by considering two key dimensions: family cohesion and family adaptability. Cohesion refers to the emotional bond among family members, while adaptability concerns the family’s ability to adjust to changes in roles and relationships. The quality of communication within the family plays a crucial role in facilitating or inhibiting cohesion and adaptability (Olson 1976).

Olson’s Circumplex Model is highly regarded for its diagnostic and therapeutic utility in understanding modern families. Healthy families typically exhibit moderate levels of cohesion, adaptability, and quality communication. Olson outlined extremes that families may experience, such as being disengaged or enmeshed. Disengaged families lack clear rules and leadership, while enmeshed families are overly involved in each other’s affairs, often at the expense of individual identities.

Remarried families face unique challenges as they integrate previous family systems into new ones. Unlike the smooth transitions portrayed in TV shows like the Brady Bunch, Full House, Modern Family, forming stepfamilies involves complex adjustments. The goals of remarried couples forming stepfamilies are often similar to those of first married couples: providing for the needs of spouses, children, and pets; creating a secure home environment; enjoying life together with loved ones; ensuring financial stability; and raising children into successful adulthood.

Effective strategies for stepfamilies include acknowledging and addressing the grief and transitions experienced by all members. Stepchildren and remarried parents may carry lingering grief from past divorces or deaths. Although it may be tempting to overlook these emotions and focus on moving forward, it is essential to confront them. Research, self-help resources, and websites offer support for navigating grief and transitions within stepfamilies. Addressing grief can strengthen the bonds within the stepfamily and foster a sense of cohesion.

It’s crucial for stepparents to focus on the functioning of their family rather than getting caught up in its structure. Whether you’re a combination of his, hers, theirs, or anything else, what matters most is how well the family operates. This includes ensuring that certain criteria are met and working effectively. It also means being able to adapt and accommodate when adjustments are necessary. A functional, adaptable, and cohesive family is better equipped to handle both everyday challenges and more significant stressors.

One valuable lesson from public educators that applies to stepfamilies is the importance of transparency. When assigning chores or administering discipline, it’s essential to make the process clear to everyone and ensure fairness for all involved. If any biased processes are identified, it’s crucial to address them openly so that all children understand the fairness of the rules.

In his book “The Intentional Family: Simple Rituals to Strengthen Family Ties,” William J. Doherty emphasizes the importance of family rituals in building cohesion. These intentional efforts help connect family members and reinforce bonds over time. Especially in the early stages of forming a stepfamily, rituals like traveling together, celebrating birthdays and holidays, and engaging in shared activities play a vital role in fostering cohesion. While family reunions can be enjoyable and meaningful, it’s important to recognize that not all family members may participate, and that’s okay.

ANALYZING FAMILY STRUCTURES

Big Blend Theory

Watch the video, Parenting Strategies for Blended Families, and answer the following questions:

- List three facts or main ideas in the video that you found interesting or important.

- What was your reaction to the video?

- Describe something left unanswered you would like to know more about, or what information was left out that might aide your understanding of the topic.

- Did this video change any ideas or opinions you had before you saw it? Why or why not? If it aligns with your current thinking, describe how it broadened your understanding of the topic.

- What strategies stood out the most that would support the healthy function of blended families?

“Big Bend Theory” by Katie Conklin, Lemoore College is licensed under CC BY 4.0

Stepfamilies often contend with unresolved issues from past marriages and family systems, which can affect cohesion. In such cases, it’s essential to continue gathering as a family and address any concerns openly. The happiness of a stepfamily should not be solely determined by the least happy member. Despite the challenges, stepfamilies can be happy families with concerted efforts to navigate complexities and create positive memories. If stepchildren leave home with unresolved issues, it’s important for the couple to accept their best efforts, focus on their relationship, and move forward together. While it’s crucial to meet the needs of children living at home, ultimately, the husband and wife are the ones who will spend their lives together.

As previously stated, remarriage refers to when a couple gets married after one or both of them have been previously married. While some couples do divorce and then remarry each other, this is quite rare. More commonly, remarriage after divorce happens when the individuals are in their twenties. As people move into their thirties, forties, fifties, and beyond, the likelihood of remarriage decreases. Typically, men remarry sooner than women after a divorce.

Entering the dating scene after a divorce can be daunting, especially for those who have been out of it for a while. Many newly divorced individuals feel uncertain about their ability to navigate new relationships. This feeling is often justified because, during marriage, people tend to focus on their roles as spouses and parents rather than on developing dating skills. Men usually transition back into dating more quickly, seeking social and emotional connections with new acquaintances. On the other hand, women often have more extensive social networks and family relationships after divorce.

When searching for a new partner, individuals tend to seek someone with similar backgrounds and interests who they perceive as compatible. Remarriage seekers, however, apply a unique filter compared to those who have never been married. They aim to avoid repeating past mistakes and often look for qualities in a partner that their ex-spouse lacked. Like everyone in the marriage market, remarriage seekers try to maximize rewards while minimizing costs, as explained by social exchange theory. Figure 6.9 illustrates some of the rewards and costs that remarriage seekers typically consider. It’s observed that men generally have more rewards when re-entering the marriage market compared to women. Additionally, the absence of children plays a role, contributing to why men tend to remarry sooner than women.

Figure 6.9. The Rewards and Costs Considered in Remarriage

Source: Hammond, Ron, Paul Cheney, Raewyn Pearsey. 2021. Sociology of the Family. Ron J. Hammond & Paul W. Cheney. Retrieved April 2, 2024 (https://freesociologybooks.com/Sociology_Of_The_Family/09_Marriage_and_Other_Long-Term_Relationships.php).

The “rewards” refer to desirable qualities that both men and women seek in potential partners. Among these, financial security holds significant appeal. Financial stability, encompassing adequacy, comfort, and even luxury is highly valued. Sociologists have long discussed the concept of relative deprivation, which refers to how we perceive our own advantages or disadvantages compared to others. Essentially, we gauge our circumstances based on past experiences and compare them to those of others.

For instance, a single mother with three children may find a potential partner attractive if he can alleviate some of her financial strain. Similarly, a middle-class divorcee with children may seek someone who can maintain their socioeconomic status. Conversely, a wealthy divorcee might prioritize finding a partner who can offer luxury.

When considering the importance of financial stability or any other desirable trait in a remarriage partner, it’s crucial to understand the concept of “perceived advantage or disadvantage.” Remarried individuals, like all of us, evaluate their current rewards in comparison to past experiences, and they do so subjectively, taking emotions into account. Some may prioritize companionship or trustworthiness over financial factors.

After divorce, both men and women experience a significant decrease in sexual activity compared to when they were married. The desire for sex and intimacy often drives individuals to seek out new partners. Loneliness is a prevalent issue for divorcees. While men tend to quickly find dating partners and may fulfill their need for intimacy through dating, women may rely on existing relationships with children, family, and friends, which may not fully meet their emotional and social needs compared to a romantic partner.

As straightforward as it may seem, the availability of a desirable partner makes them more attractive. Someone who isn’t deeply committed or engaged in a relationship is immediately open to interaction and potential relationship development. Many individuals seek out new partners as a way to cope with the pain and grief of divorce. There’s nothing inherently wrong with this approach; healthy dating and connections can aid in the healing process. However, rushing into marriage during the still-recovering phase can be harmful. Once the emotional wounds heal, one may realize that they aren’t compatible with their new partner after all. Second, third, and fourth marriages carry higher divorce risks compared to first marriages. You might have heard of “rebound relationships or marriages,” which are often seen as hasty and ill-advised.

Both friendship and love are fundamental human needs. Adjusting to the absence of these connections, even if one has children, can be challenging. Adults often seek companionship and romantic love. For single parents with custody (and the few single fathers who have custody), finding a co-parent who can live with the family is highly desirable. Single parents want their children to have the influence of two parents and may actively seek out a mother or father figure for their kids. For both younger and older singles, the presence of children becomes a significant factor. Some younger divorcees may hesitate to enter a relationship with a single parent, while others may be open to it. Generally, having children under a divorced woman’s care tends to lower the likelihood of her remarrying.

Physical attractiveness holds significance for many individuals who are considering remarriage. It may play a more prominent role for some compared to others. Similar to never-married individuals, divorced men also take physical attractiveness into account when selecting a new partner. However, they weigh it alongside other important attributes, considering their past marital experiences and challenges. When entering a marriage, it’s beneficial for partners to have complementary needs. For instance, if one partner seeks care while the other desires to provide it, their needs complement each other. Some single individuals, particularly men, may actively seek to raise children, reflecting healthy motives. This desire for companionship aligns well with single mothers seeking co-parents. However, not all needs are complementary, and it’s unrealistic to expect one person to fulfill all their partner’s needs at all times.

Equity is a concept often used by remarried couples to evaluate their relationship’s rewards and costs. It refers to the overall sense of receiving a fair deal considering all perceived benefits and drawbacks. While an outsider might perceive an imbalance in give-and-take, equity is subjective and varies between individual spouses. For example, a remarried woman may value her new husband’s involvement with her children more than other contributions. Equity is fluid and can change as new needs arise or circumstances evolve within the family.

Educational attainment, such as having a college degree, often correlates with higher income and desirable traits in a potential partner. College graduates tend to exhibit traits like delayed gratification and have diverse family role expectations, making them more attractive in the marriage market. Additionally, owning a home, as opposed to renting, provides benefits such as privacy, financial stability, and clear boundaries that contribute to the development of a remarriage and new family system.

When it comes to health considerations, older individuals, particularly women, often prioritize the current and future health of a potential partner. Caregiving responsibilities, especially for elderly individuals, can significantly impact relationship dynamics and future plans. While caregiving is common, it’s seldom a desired role for potential mates. Women, in particular, may face challenges in finding new partners due to custody arrangements and caregiving responsibilities, which can affect their ability to engage in new relationships. Overall, finding a suitable partner involves considering various factors, including financial stability, health, and mutual compatibility, to ensure a successful remarriage.