28 The Plight of the Native Americans

The Plight of the Native Americans

As railroads, farms, and cattle ranches disrupted buffalo migration patterns and settled the Great Plains, the region’s earliest inhabitants took notice. The situation was aggravated by the government’s desire to confine the Plains Indians to reservations, teach them to cultivate land like whites, and leave their hunting and roaming past behind. The Plains Wars which followed resulted in a series of forts along the major trails to the West. As the Plains Indians were increasingly neutralized by the government, the farmers could focus on big business as their primary adversary.

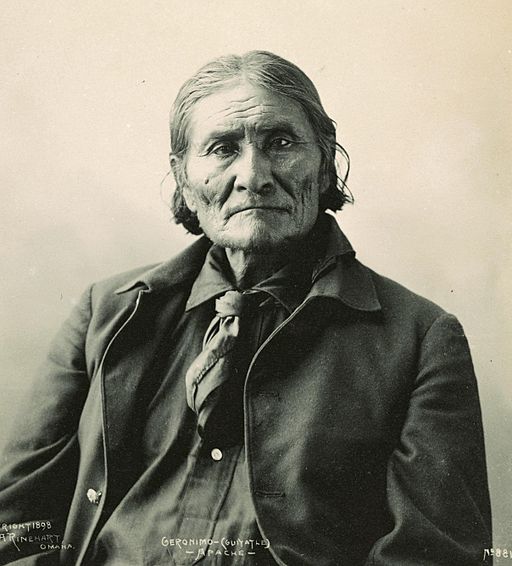

As in the East, expansion into the plains and mountains by miners, ranchers, and settlers led to increasing conflicts with the Native Americans of the West. Many tribes of Native Americans — from the Utes of the Great Basin to the Nez Perces of Idaho — fought the whites at one time or another. But the Sioux of the Northern Plains and the Apache of the Southwest provided the most significant opposition to frontier advance. Led by such resourceful leaders as Red Cloud and Crazy Horse, the Sioux were particularly skilled at high-speed mounted warfare. The Apaches were equally adept and highly elusive, fighting in their environs of desert and canyons.

The Plains Wars

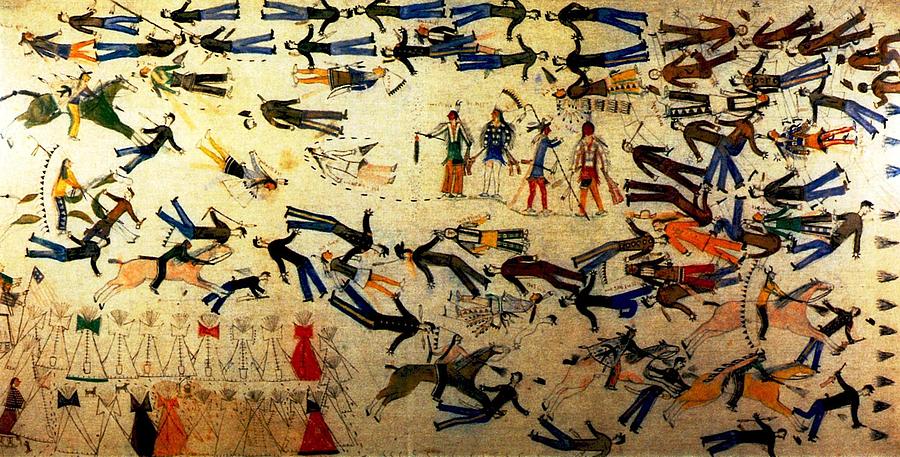

The nomadic plains Indians had become efficient hunters and warriors due to the Spanish introduction of the horse in the 1500s. No longer did they find it necessary to frighten whole herds of bison over cliffs only to use a few animals. Their newfound abilities as horsemen had given them a ferocious edge over their prey and their enemies.

Endowed with all of humanity’s peculiarities, Indigenous Americans traveled, traded, made war and peace, and adapted to the cultures they came in contact with. If a neighboring people had found a better way to do something, it generally became an accepted practice. When Europeans arrived, Native Americans quickly adopted firearms, metal tools, and horses. So thoroughly was the horse adapted into indigenous culture that it became a fixture, ever-present from the beginning of time in native myth.

Reservations

In order to maintain peace between settlers, emigrants, and indigenous peoples, the government attempted to open a corridor through the Plains by pushing natives into northern and southern reservations. This, it was hoped, would allow safe passage of wagon trains; but a string of prairie forts was developed along this corridor for added security. The Horse Creek Council of 1851 established a large reservation in North Dakota and Montana—The northern boundary of this corridor. The southern boundary was established in 1853 at the Fort Atkinson Council in Kansas. Roughly, the agreement was that the tribes would stay on their side of the lines and the government would compensate for the lost land with annual payments and never violate the agreement.

Problems of Perception

Problems of perception and treaty failures ensured that peace would be short-lived. From the White perspective the presence of thousands of Indians at the councils lent legitimacy to the proceedings. The Indian viewpoint was that a few chiefs could not speak for the whole. Both sides mistakenly assumed that the government would be able (and willing) to channel settlement away from the reservations. Ultimately, the failure to make annual payments, new gold finds near Pike’s Peak, Colorado and the Black Hills of South Dakota, as well as the introduction of land-hungry settlers, sank the earlier agreements in a mire of blood and warfare.

War came, among other things, due to gold, disruption, and treaty failures. In 1848, gold was discovered at Sutter’s Mill in Coloma, California, thus beginning the greatest migration of humanity in the Western hemisphere. Migrants went overland on the Oregon and California Trails, over oceans from as far away as China and Australia, and even from amongst indigenous peoples themselves.

Farming and ranching involved the obvious disruptions involved in permanent settlement of the land which hitherto had been occupied seasonally and briefly by Indians. Farmers put up fences to keep cattle out while ranchers put up fences to keep them in. Railroads bringing supplies to these settlers cut East/West across the prairie effectively creating a thousand-mile cattle guard which buffalo were hesitant to cross during their North/South migrations. Overland emigrants used up fuel, grass, and indigenous goodwill in great quantities, all of which eventually brought government involvement on the Plains.

Conflicts with the Plains Indians worsened after an incident where the Dakota (part of the Sioux nation), declaring war against the U.S. government because of long-standing grievances, killed five white settlers. Spontaneously, between five and eight hundred white settlers in territory ceded by the Sioux were then massacred, quite possibly without their even knowing of the government’s failure to uphold its treaty agreements. Bad feelings and racism on both sides turned to outright hatred and, over a period of a quarter century, the Plains Indians lost their homeland.

Rebellions and attacks continued through the Civil War. In 1876 the last serious Sioux war erupted, when the Dakota gold rush penetrated the Black Hills. The Army was supposed to keep miners off Sioux hunting grounds, but effectively did little to protect Sioux lands. When ordered to take action against bands of Sioux hunting on the range according to their treaty rights, however, it moved quickly and vigorously.

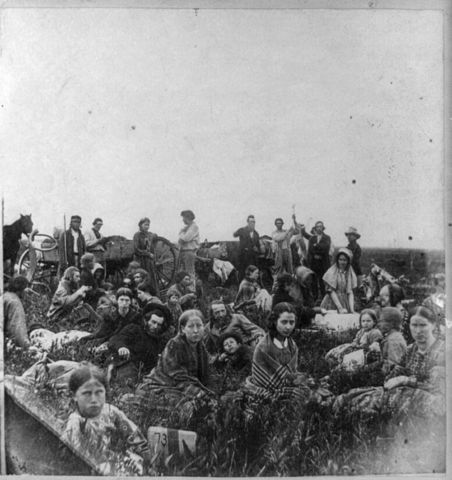

In 1876, after several indecisive encounters, Colonel George Custer, leading a small detachment of cavalry encountered a vastly superior force of Sioux and their allies on the Little Bighorn River. Custer and his men were completely annihilated. Nonetheless the Native-American insurgency was soon suppressed. Later, in 1890, a ghost dance ritual on the Northern Sioux reservation at Wounded Knee, South Dakota, led to an uprising and a last, tragic encounter that ended in the death of about 150 Sioux men, women, and children.

Long before this, however, the way of life of the Plains Indians had been destroyed by an expanding white population, the coming of the railroads, and the slaughter of the buffalo, almost exterminated in the decade after 1870 by the settlers’ indiscriminate hunting.

The Apache wars in the Southwest dragged on until Geronimo, the last important chief, was captured in 1886.

Government policy ever since the Monroe administration had been to move the Native Americans beyond the reach of the white frontier. But inevitably the reservations had become smaller and more crowded. Some Americans began to protest the government’s treatment of Native Americans. Helen Hunt Jackson, for example, an Easterner living in the West, wrote A Century of Dishonor (1881), which dramatized their plight and struck a chord in the nation’s conscience. Most reformers believed the Native American should be assimilated into the dominant culture.

Assimilation

Assimilation of the American Indian had been an on-again, off-again goal since at least as early as Thomas Jefferson’s administration. Now, toward the end of the 1800s, eastern interests sponsored these boarding schools which forcibly removed Indian children from their homes in the West and educated them back East. The federal government even set up a school in Carlisle, Pennsylvania, in an attempt to impose white values and beliefs on Native-American youths. (It was at this school that Jim Thorpe, often considered the best athlete the United States has produced, gained fame in the early 20th century.)

Dawes Severalty Act

In 1887 the Dawes (General Allotment) Act reversed U.S. Native- American policy, permitting the president to divide up tribal land and parcel out 160 acres of land to each head of a family. Such allotments were to be held in trust by the government for 25 years, after which time the owner won full title and citizenship. Lands not thus distributed, however, were offered for sale to settlers. This policy, however well-intentioned, proved disastrous, since it allowed more plundering of Native-American lands. Moreover, its assault on the communal organization of tribes caused further disruption of traditional culture.

Ghost Dance and Wounded Knee

In the last major pan-Indian movement, the Ghost Dance was a rejection of Easterners attempts at assimilation. In 1889, Wovoka, a Paiute,- claimed a revelation instructing all Indians to forsake white ways and to dance. Their reward would be the earth’s opening up and consuming all whites followed by a return of the buffalo and Indian lands. To this Sitting Bull added that the ghost dancer’s white shirt would stop white bullets. This, the Army took as an ominous sign of impending warfare and moved to stop the dance.

Adapted from “Chapter 13 Conquest & Empire” by Trina Ulrich et al is licensed CC-BY-NC-SA